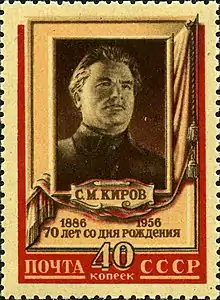

Sergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov[lower-alpha 1] (born Kostrikov;[lower-alpha 2] 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary.

Sergei Kirov | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Сергей Киров | |||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp) Kirov c. 1930s | |||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijani Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||

| In office July 1921 – January 1926 | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Grigory Kaminsky | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Levon Mirzoyan | ||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary of the Leningrad Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 August 1927 – 1 December 1934 | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Post established | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Andrey Zhdanov | ||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary of the Leningrad City Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 January 1926 – 1 December 1934 | |||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Grigory Yevdokimov | ||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Andrey Zhdanov | ||||||||||||||||

| Full member of the 16th, 17th Politburo | |||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 July 1930 – 1 December 1934 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | Sergei Mironovich Kostrikov 27 March 1886[1] Urzhum, Vyatka Governorate, Russian Empire[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1 December 1934 (aged 48)[1] Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Manner of death | Assassination | ||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow | ||||||||||||||||

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1904–1918) All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1918–1934) | ||||||||||||||||

Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Kirov became an Old Bolshevik and personal friend to Joseph Stalin, rising through the Communist Party of the Soviet Union ranks to become head of the party in Leningrad and a member of the Politburo.

On 1 December 1934, Kirov was shot and killed by Leonid Nikolaev at his offices in the Smolny Institute for unknown reasons; Nikolaev and several suspected accomplices were convicted in a show trial and executed less than 30 days later. Kirov's death was later used as a pretext for Stalin's escalation of political repression in the Soviet Union and the events of the Great Purge, with complicity as a common charge for the condemned in the Moscow Trials. Kirov's assassination remains controversial and unsolved, with varying theories regarding the circumstances of his death.[2]

Early life

Sergei Mironovich Kostrikov was born on 27 March [O.S. 15 March] 1886 in Urzhum in Vyatka Governorate, Russian Empire, as one of seven children born to Miron Ivanovich Kostrikov and Yekaterina Kuzminichna Kostrikova (née Kazantseva). Their first four children had died young, while Anna (born 1883), Sergei (1886), and Yelizaveta (1889) survived.[3]

Miron, an alcoholic, abandoned the family around 1890, and Yekaterina died of tuberculosis in 1893. Sergei and his sisters were raised for a brief time by their paternal grandmother, Melania Avdeyevna Kostrikova, but she could not afford to take care of them all on her small pension of 3 rubles per month. Through her connections, Melania succeeded in having Sergey placed in an orphanage at the age of seven, but he saw his sisters and grandmother regularly.[4]

In 1901, a group of wealthy benefactors provided a scholarship for Kirov to attend an industrial school at Kazan. After gaining his degree in engineering, Kirov moved to Tomsk, a city in Siberia, where he became a Marxist and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1904.[5]

Revolutionary

Kirov was a participant in the 1905 Russian Revolution and was arrested, joining with the Bolsheviks soon after being released from prison. In 1906, he was arrested once again, but this time jailed for over three years, charged with printing illegal literature. Soon after his release, Kirov again took part in revolutionary activity, once again being arrested for printing illegal literature. After a year in custody, Kirov moved to the Caucasus, where he stayed until the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II after the February Revolution in March 1917.

By this time, Kirov had shortened his last name from Kostrikov to Kirov, a practice common among Russian revolutionaries of the time. Kirov began using the pen name "Kir," first publishing under the pseudonym "Kirov" on 26 April 1912. One account states that he chose the name "Kir," the Russian version of Cyrus (from the Greek Kūros), after a Christian martyr in third-century Egypt from an Orthodox calendar of saints' days, and Russifying it by adding an "-ov" suffix. A second story is that Kirov based it on the name of the Persian king Cyrus the Great.[6]

Kirov became commander of the Bolshevik military administration in Astrakhan, and fought for the Red Army in the Russian Civil War until 1920. Simon Sebag Montefiore writes: "During the Civil War, he was one of the swashbuckling commissars in the North Caucasus beside Ordzhonikidze and Mikoyan. In Astrakhan he enforced Bolshevik power in March 1919 with liberal bloodletting; more than 4,000 were killed. When a bourgeois was caught hiding his own furniture, Kirov ordered him shot."[7]

Career

In 1921, Kirov became First Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, the Bolshevik party organization in the Azerbaijan SSR.[1] Kirov was a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin, the successor of Vladimir Lenin, and in 1926 he was rewarded with command of the Leningrad party organization. Kirov was a close personal friend of Stalin, and a strong supporter of industrialisation and forced collectivisation. At the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in 1930, Kirov stated: "The General Party line is to conduct the course of our country industrialization. Based on the industrialisation, we conduct transformation of our agriculture. Namely, we centralise and collectivise."[8]

In 1934, at the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Kirov delivered the speech called "The Speech of Comrade Stalin Is the Program of Our Party," which refers to Stalin's speech delivered at the Congress earlier. Kirov praised Stalin for everything he had done since the death of Lenin. Moreover, Kirov personally named and ridiculed Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov and Mikhail Tomsky—former party allies of Stalin. Bukharin and Rykov were later tried in the show trial called The Trial of the Twenty-One accused of Kirov's death, while Tomsky committed suicide expecting his arrest by the NKVD.

Reputation

_49.jpg.webp)

After Kirov's assassination, he acquired a reputation for having repeatedly stood up to Stalin in private and for becoming so popular that he was a threat to Stalin's supremacy. He did display some independence from Stalin.[9] Allegedly, in 1932, Stalin wanted to have Martemyan Ryutin executed for writing an attack on his leadership, but Kirov and Sergo Ordzhonikidze talked him out of it.[10] Alexander Orlov, who defected to the West, listed a series of incidents in which Kirov allegedly clashed with Stalin, based on rumors he must have heard from fellow NKVD officers.[11] Kirov's reputed rivalry is a major theme of the historical novel Children of the Arbat, by Anatoli Rybakov, who wrote:

In his hunger for popularity, Kirov opted for the simple style. He lived on Kamennoostrovsky Prospekt in a large house, inhabited by all sorts of people, he walked to work, wandered on his own around the streets of the city, took his children for rides in his car and played hide-and-seek with them in the yard ... as if to emphasize that Stalin lived in the Kremlin, with guards, didn't wander the streets or play hide-and-seek with his children, thus underlining the idea that Stalin was afraid of the people, whereas Kirov was not.[12]

At the end of the Communist Party's Seventeenth Congress, in February 1934, there is reputed to have been a scandal, when Kirov topped the poll in elections to the Central Committee, and Stalin's acolyte, Lazar Kaganovich ordered a number of ballots be destroyed so that Stalin and Kirov could share top billing.[13] Amy Knight, a historian of the Soviet Union, suggests that whereas Kirov "might have toed the line as others did, on the other hand he might have acted as a rallying point for those who wanted to oppose his [Stalin’s] dictatorship." Further, Knight suggests that Kirov would not have been a willing accomplice when the full force of Stalin's terror was unleashed in Leningrad.[14]

Knight's contention is supported by the fact that whereas most of the elite tried to anticipate what Stalin desired and to act accordingly, Kirov did not always do what Stalin wanted. In 1934, Stalin wanted Kirov to come to Moscow permanently. Whereas all the other members of the Politburo would have complied, Stalin accepted that, as Kirov had no desire to leave Leningrad, he would not come to Moscow until 1938. Again, when Stalin wanted Filipp Medved moved from the Leningrad NKVD to Minsk, Kirov refused to agree and, rarely for Stalin, he had to accept defeat.[9]

However, it would be wrong to claim Kirov had moral superiority over his colleagues. In modern St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad), there is a museum to show all the gifts that Kirov accepted and used from inhabitants and businesses over which he ruled. The guides of the museum imply that these were bribes paid by people who needed Kirov's favor. The Croatian communist Ante Ciliga, who was in Russia in the 1920s, and backed Leon Trotsky against Stalin, did not share the admiration for Kirov:

Kirov, by his manners and methods, reminded me of the cultured high officials of the Austrian administration.... In the office of Kirov, governor of Leningrad in 1929, one felt that the revolution had already been tamed and canalized.... Kirov was hated, with a hatred that was as fierce as it was impotent.[15]

Assassination

In the first days when Leningrad was orphaned, Stalin rushed there. He went to the place where the crime against our country was committed. The enemy did not fire at Kirov personally. No! He fired at the proletarian revolution.

On the afternoon of Saturday, 1 December 1934, Kirov's assassin, Leonid Nikolayev, arrived at the Smolny Institute offices and made his way to the third floor unopposed, waiting in a hallway until Kirov and his bodyguard Borisov stepped into the corridor. Borisov appeared to have stayed some 20 to 40 paces behind Kirov, with some sources alleging Borisov parted company with Kirov in order to prepare his lunch.[17] Kirov turned a corner and passed Nikolayev, who then drew his revolver and shot Kirov in the back of the neck.[17]

Nikolayev was well known to the NKVD, which had arrested him for various petty offences in recent years. Various accounts of his life agree that he was an expelled Party member and a failed junior functionary, with a murderous grudge and an indifference to his own survival. Nikolayev was unemployed, with a wife and child, and in financial difficulties. According to Orlov, Nikolayev had allegedly told a friend he wanted to kill the head of the party control commission that had expelled him. Nikolayev's friend reported this to the NKVD.[18] Zaporozhets then allegedly enlisted Nikolayev's "friend" to contact him, giving him money and a loaded 7.62 mm Nagant M1895 revolver.[18]

However, Nikolayev's first attempt at killing Kirov failed. On 15 October 1934, Nikolayev packed his Nagant revolver in a briefcase and entered the Smolny Institute where Kirov now worked. Although Nikolayev was initially passed by the main security desk at Smolny, he was arrested after an alert guard asked to examine his briefcase, which was found to contain the revolver.[18] According to dissident Alexander Gregory Barmine, a few hours later, Nikolayev's briefcase and loaded revolver were returned to him, and he was told to leave the building. The author thus claims that, though Nikolayev had clearly broken Soviet laws, the security police had inexplicably released him from custody and permitted him to retain his loaded pistol.[19]

According to Barmine's account, with Stalin's approval, the NKVD had previously withdrawn all but four police bodyguards assigned to Kirov. These four guards accompanied Kirov each day to his offices at the Smolny Institute, and then left. On 1 December 1934, the usual guard post at the entrance to Kirov's offices was supposedly left unmanned, even though the building housed the chief offices of the Leningrad party apparatus and was the seat of the local government.[18][20] According to some reports, only a single friend, Commissar Borisov, an unarmed bodyguard of Kirov's, remained.[20][17] Given the circumstances of Kirov's death, Barmine stated that "the negligence of the NKVD in protecting such a high party official was without precedent in the Soviet Union."[19]

Kirov was cremated and his ashes interred in the Kremlin Wall necropolis in a state funeral, with Stalin and other prominent members of the CPSU personally carrying his coffin.

Aftermath

After Kirov's death, Stalin called for swift punishment of the traitors and those found negligent in Kirov's death. Nikolayev was tried alone and secretly by Vasili Ulrikh, Chairman of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR. He was sentenced to death by shooting on 29 December 1934, and the sentence was carried out that very night. The Soviet government, led by Stalin, stated that their investigation proved that the assassin was acting on behalf of a secret Zinovievist group.[21] The hapless Commissar Borisov died the day after Kirov's assassination, allegedly falling from a moving truck while riding with a group of NKVD agents. According to Orlov, Borisov's wife was committed to an insane asylum, while Nikolayev's mysterious "friend" and alleged provocateur, who had supplied him with the revolver and money, was later shot on Stalin's personal orders.[18]

Several NKVD officers from the Leningrad branch were convicted of negligence for not adequately protecting Kirov, and sentenced to prison terms of up to ten years. According to Barmine, none of the NKVD officers were executed in the aftermath, and none actually served time in prison. Instead, they were transferred to executive posts in Stalin's Gulag labour camps for a period of time—in effect, a demotion.[19] According to Nikita Khrushchev, the same NKVD officers were later shot in 1937.[22] Lajos Magyar, a Hungarian communist and refugee from the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, was falsely accused of complicity in Kirov's assassination. Magyar was convicted as a "Zinovievite-Terrorist" and sent to a Gulag, where he died in 1940.

According to Soviet dissident Alexander Gregory Barmine, a Communist Party communiqué initially reported that Nikolayev had confessed his guilt, not only as an assassin, but as an assassin in the pay of a "fascist power," having received money from an unidentified "foreign consul" in Leningrad.[23] The same author claims 104 defendants who were already in prison at the time of Kirov's assassination, and who had no demonstrable connection to Nikolayev, were found guilty of complicity in the "fascist plot" against Kirov, and summarily executed.[23] However, a few days later, during a subsequent Communist Party meeting of the Moscow District, the Party secretary announced in a speech that Nikolayev had been personally interrogated by Stalin the day after the assassination, something unheard-of for a party leader such as Stalin to have done:[24]

Comrade Stalin personally directed the investigation of Kirov's assassination. He questioned Nikolayev at length. The leaders of the Opposition placed the gun in Nikolayev's hand![24]

Other speakers duly rose to condemn the Opposition: "The Central Committee must be pitiless—the Party must be purged... the record of every member must be scrutinized...." No one at the meeting mentioned the initial theory that fascist agents had been responsible for the assassination.[24] Barmine asserts Stalin even used the Kirov assassination to eliminate the remainder of the Opposition leadership, accusing Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Abram Prigozhin, and others who had stood with Kirov in opposing Stalin (or who had simply failed to acquiesce to Stalin's views), of being "morally responsible" for Kirov's murder, and therefore guilty of complicity.[23] Barmine also claimed that Stalin arranged the murder with the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, who armed Nikolayev and sent him to assassinate Kirov.[25]

Kirov's assassination became a major event in the history of the Soviet Union because it was used by Stalin as an excuse to justify his reign of terror known as the Great Purge.[26] At the time of Kirov's murder, Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, was out of the country; his daughter Tanya implied that Litvinov realised this event might be an excuse for Stalin to unleash a reign of terror.[27] This view was confirmed by Anastas Mikoyan's son, who stated that the murder of Kirov had certain similarities to the burning of the Reichstag in Nazi Germany in 1933. The fire at the Reichstag was organized by the Nazis as a pretext for the mass persecution of the Communists and Social Democrats in Germany. The physical removal of Kirov meant elimination of a future potential rival for Stalin, but the principal objective, as with the fire at the Reichstag, was to manufacture an excuse for repression and control.[28]

According to Alexander Orlov, an anti-Soviet defector to the United States, Stalin then ordered Yagoda to arrange the assassination of Kirov. Orlov said that Yagoda ordered Medved's deputy, Vania Zaporozhets, to undertake the job. Zaporozhets returned to Leningrad in search of an assassin; in reviewing the files he found the name of Leonid Nikolayev.[18] According to another Soviet defector, Grigori Tokaev, a real oppositionist underground group assassinated Kirov.[29] Author and Menshevik scholar Boris Nikolaevsky argued: "One thing is certain: the only man who profited by the Kirov assassination was Stalin."[30]

Nikita Khrushchev, in his controversial Secret Speech in 1956, said that the murder of Kirov was organized by NKVD agents.[31] Khrushchev claimed that the NKVD agents tasked with protecting Kirov were eventually shot in 1937, and assumed that this was to "cover the traces of the organisers of Kirov's killing."[31] Khrushchev's and Gorbachev's governments claimed that Nikolayev was acting alone.[21] Stalin's complicity has been rejected by historians of the "revisionist school" of Soviet studies, as well as by Soviet and some Russian historians.[2]

Historians Alla Kirilina and Oleg Khlevniuk, based on extensive research of the Soviet archives, assert that the conventional narratives of Stalin's complicity in Kirov's assassination is almost entirely a myth.[32] Historian Matt Lenoe finds their case convincing, arguing that ordering a hit on Kirov did not make political sense for Stalin, nor did it fit with the modus operandi of Soviet politics in the mid-1930s.[32]

Furthermore, according to Lenoe, "if we follow accepted rules of historical evidence–privileging, for example, archival documentation over third-hand transmitted by word of mouth– then almost all of the conventional narrative disappears". He notes that most of the evidence for Stalin's complicity derives from his own show trials, rumors reported by Soviet defectors and Khrushchev-era investigations which aimed to absolve the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of responsibility for the Great Purge by blaming Stalin alone.[32]

Pospelov Commission investigation

In December 1955, after Khrushchev assumed control of the Party, the Presidium of the Central Committee entrusted Pyotr Pospelov, Secretary of the Central Committee, to form a commission to investigate the repression of the 1930s; this was the same Pospelov who had drafted the famous "Secret Speech" for Khrushchev at the 20th Congress. Khrushchev stated:

It must be asserted that to this day the circumstances surrounding Kirov's murder hide many things which are inexplicable and mysterious and demand a most careful examination. There are reasons for the suspicion that the killer of Kirov, Nikolayev, was assisted by someone from among the people whose duty it was protect the person of Kirov. A month and a half before the killing, Nikolayev was arrested on the grounds of suspicious behavior, but he was released and not even searched. It is an unusually suspicious circumstance that when the Chekist [Borisov] assigned to protect Kirov was being brought for an interrogation, on 2 December 1934, he was killed in a car "accident" in which no other occupants of the car were harmed. After the murder of Kirov, top functionaries of the Leningrad NKVD were relieved of their duties and were given very light sentences, but in 1937 they were shot. We can assume that they were shot in order to cover the traces of the organizers of Kirov's killing.[22]

Pospelov subsequently spoke to Dr. Kirchakov and former nurse Trunina, former members of the party, who had been mentioned in a letter by another member of the commission, Olga Shatunovskaya, as having knowledge of the Kirov murder. Kirchakov confirmed that he did talk to Shatunovskaya and Trunina about some of the unexplained aspects of the Kirov murder case and agreed to provide the commission with a written deposition. He stressed that his statement was based on the testimony of one Comrade Yan Olsky, a former NKVD officer who was demoted after Kirov's murder and transferred to the People's Supply System .

In his deposition, Kirchakov wrote that he had discussed the Kirov's murder and the role of Fyodor Medved with Olsky. Olsky was of the firm opinion that Medved, Kirov's friend and NKVD security chief of the Leningrad branch, was innocent of the murder. Olsky also told Kirchakov that Medved had been barred from the NKVD Kirov assassination investigation. Instead, the investigation was carried out by a senior NKVD chief, Yakov Agranov, and later by another NKVD bureau officer whose name he did not remember.

The other NKVD official may have been Yefim Georgievich Yevdokimov (1891–1939), a Stalin crony, mass-killing specialist, and architect of the Shakhty purge trials, who continued to lead a secret police team within the NKVD even after technically retiring from the OGPU in 1931. During one of the committee sessions, Olsky said he was present when Stalin asked Leonid Nikolayev why Comrade Kirov had been killed. To this Nikolayev replied that he carried out the instruction of the "Chekists" (meaning the NKVD) and pointed towards the group of "Chekists" (NKVD officers) standing in the room; Medved was not among them.

Khrushchev's report, On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, was later read at closed-door Party meetings. Afterwards, new material was received by the Pospelov Committee, including the assertion by Kirov's chauffeur, Kuzin, that Commissar Borisov, Kirov's friend and bodyguard, who was responsible for Kirov's round-the-clock security at the Smolny Institute, was intentionally killed, and that his death in a road accident was not an accident at all.[33]

Politburo Commission headed by A. Yakovlev

The last attempt in the Soviet Union to review the Kirov murder case was the Politburo Commission headed by Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev which was established in the Gorbachev period in 1989, shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The investigating team included personnel from the USSR Procurator's Office, the Military Procuracy, the KGB, and various archival administrations. After two years of investigations, the working team of the Yakovlev Commission concluded that: in this affair no materials objectively support Stalin's participation or NKVD participation in the organization and carrying out of Kirov's murder.[34]

Legacy

Many cities, streets and factories were named or renamed after Kirov in Russia, including the cities of Kirov (formerly Vyatka) and Kirov Oblast, Kirovsk (Murmansk Oblast), Kirov (Kaluga Oblast), Kirovohrad (formerly Zinovyevsk, now Kropyvnytskyi[35]) and Kirovohrad Oblast (Ukrainian SSR; now Ukraine), Kirovabad (Azerbaijani SSR; now Ganja, Azerbaijan), Kirovakan (Armenian SSR; now Vanadzor, Armenia), the Kirovskaya station of the Moscow Metro (now Chistye Prudy station), the Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky Ballet), the massive Kirov Plant in Saint Petersburg, Kirov Square in Yekaterinburg, the Kirov Islands in the Kara Sea, and various small settlements.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the locations and buildings named after Kirov have been renamed, especially outside of Russia. In order to comply with Ukrainian decommunization laws, Kirovohrad was renamed Kropyvnytskyi by the Ukrainian parliament on 14 July 2016.[35] In 2019, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine approved the change of the oblast's name to Kropyvnytskyi Oblast, or Kropyvnychchyna.[36]

The S. M. Kirov Forestry Academy in Leningrad was named after him, but renamed the Saint Petersburg State Forest Technical University.[37] For many years, a huge granite and bronze statue of Kirov dominated the city of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, erected on a hill in 1939. The statue was dismantled in January 1992, shortly after Azerbaijan gained its independence.[38]

The Kirov Prize, a speedskating match in the city of Kirov, was named for him. The Kirov Prize is the oldest annual organised race in speedskating, apart from the World Speed Skating Championships and the European Speed Skating Championships.

The English communist poet John Cornford wrote an eponymous poem in his honour.[39]

The Soviet Navy cruiser Kirov was named after him, and by extension the Kirov-class cruiser.[40] The Kirov name was again used for the battlecruiser Kirov and the Kirov-class battlecruiser.

The Khai-3 tailless airplane was also named after him.

Personal life

Kirov was married to Maria Lvovna Markus (1885–1945) from 1911, although they never formally registered their relations. Yevgenia Kostrikova (1921–1975), who claimed to be Kirov's daughter, was a famous tank company commander and World War II veteran.

Honours and awards

See also

References

- Sergei Kirov. Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Popson, Nancy. "Who Killed Kirov? The Crime of the Century". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Lenoe, pp. 128–129

- Lenoe, pp. 129–132

- Georges Haupt, and Jean-Jacques Marie (1974). Makers of the Russian Revolution, Biographies of Bolshevik Leaders. (This volume includes a translation of an autobiographical entry written by Kirov for a Soviet encyclopedia in c1925). London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 142. ISBN 0-04-947021-3.

- Lenoe, p. 186

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2005) Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Random House. p. 112. ISBN 1-4000-7678-1

- Kirov, Sergey (1944). Selected articles and speeches 1918–1934 (Russian). Moscow Russia Valovay 28: OGIZ The State political literature publisher. pp. 106–117, 269–289.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publications. p. 406. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Montefiore. The Court of the Red Tsar. p. 95.

- Orlov, Alexander (1954). A Secret History of Stalin's Crimes. London: Jarrolds. pp. passim.

- Rybakov, Anatoli (1988). Children of the Arbat. (translated by Harold Shukman) London: Hutchinson. p. 218. ISBN 0-091737-42-7.

- Medvedev, Roy (1976). Let History Judge, The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. Nottingham: Spokesman. p. 156.

- Knight, Amy (1999), Who Killed Kirov? The Kremlin's Greatest Mystery, New York: Hill and Wang. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8090-6404-5

- Ciliga, Ante (1979). The Russian Enigma. London: Ink Links. pp. 74, 120. ISBN 0-906-13322-X.

- Knight, Amy (1999). "Who Killed Kirov? The Kremlin's Greatest Mystery". New York Times.

- Knight, Amy (1999), Who Killed Kirov? The Kremlin's Greatest Mystery, New York: Hill and Wang. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8090-6404-5

- Orlov, Alexander, The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes, New York: Random House (1953)

- Barmine, p. 252

- Barmine, pp. 247–252

- Furr, Grover (11 December 2017). "Yezhov vs. Stalin: The Causes of the Mass Repressions of 1937–1938 in the USSR". Journal of Labor and Society. 20 (3): 325–347. doi:10.1163/24714607-02003004.

- Khrushchev, N.S. (1989) On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, London, p. 21

- Barmine, p. 248

- Barmine, p. 249

- Barmine, p. 55

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publications. p. 407. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Conversation between John Holroyd-Doveton and Tanya, daughter of former Soviet Foreign Secretary Maxim Litvinov

- Mikoyan, Stepan Anastasovich (1999). Stepan Anastasovich Mikoyan: An Autobiography. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-85310-916-4. LCCN 99488415. OCLC 41594812.

- Getty, John Arch; Getty, John Archibald (30 January 1987). Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933-1938. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33570-6.

- Nikolaevsky, Boris (23 August 1941) The Kirov Assassination: The New Leader

- Khrushchev, Nikita. "Speech to 20th Congress of the C.P.S.U". Marxists.org. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Lenoe, Matt (1 June 2002). "Did Stalin Kill Kirov and Does It Matter?". The Journal of Modern History. 74 (2): 352–380. doi:10.1086/343411. ISSN 0022-2801. S2CID 142829949.

- Pospelov, P. N. (1955) Materials on the Question of the Murder of S. M. Kirov. Reprinted in Svobodnaia mysl 8 (1992). Translated from the Russian by Ranjana Saxena.

- Yakovlev, A. (28 January 1991) "O dekabr'skoi tragedii 1934", Pravda, p. 3, cited in Getty, J. Archibald (1993) "The Politics of Repression Revisited", in J. Arch Getty and Roberta T. Manning, eds. Stalinist Terror New Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 46. ISBN 9780521446709

- Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Verkhovna Rada renamed Kirovograd, Ukrayinska Pravda (14 July 2016) - "The Opinion of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine in the case of renaming the Kirovohrad oblast is given". Українське право - інформаційно-правовий портал. 5 February 2019.

- "St. Petersburg State Forest Technical University". Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Best View of the Bay – What Happened to Kirov's Statue?". Azerbaijan International. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Sergei Mironovitch Kirov Poem by Rupert John Cornford". Poem Hunter. 10 May 2011.

- Yakubov, Vladimir & Worth, Richard (2009). "The Soviet Light Cruisers of the Kirov Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2009. London: Conway. pp. 82–95. ISBN 978-1-84486-089-0.

Cited sources

- Barmine, Alexander (1945). One Who Survived. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Lenoe, Matthew E. (2010). The Kirov Murder and Soviet History (ePub ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11236-8.

Further reading

- Biggart, John. "The Astrakhan Rebellion: An Episode in the Career of Sergey Mironovich Kirov", Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 54, no. 2 (April 1976), pp. 231–247. JSTOR 4207255.

- Conquest, Robert (1989). Stalin and the Kirov Murder. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505579-9.

External links

- Kirov Biography

- Leon Trotsky: On the Kirov Assassination

- "What Happened to Kirov's Statue in Baku?" Azerbaijan International, Vol. 9.2 (Summer 2001)

- Business catalog of Kirov town

- The son is not responsible for his father or is he?

- Newspaper clippings about Sergei Kirov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW