Sesame

Sesame (/ˈsɛsəmi/;[2][3] Sesamum indicum) is a plant in the genus Sesamum, also called benne.[4] Numerous wild relatives occur in Africa and a smaller number in India.[5] It is widely naturalized in tropical regions around the world and is cultivated for its edible seeds, which grow in pods. World production in 2018 was 6 million metric tons (5,900,000 long tons; 6,600,000 short tons), with Sudan, Myanmar, and India as the largest producers.[6]

| Sesame | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Sesame plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Pedaliaceae |

| Genus: | Sesamum |

| Species: | S. indicum |

| Binomial name | |

| Sesamum indicum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Sesame seed is one of the oldest oilseed crops known, domesticated well over 3,000 years ago. Sesamum has many other species, most being wild and native to sub-Saharan Africa.[5] S. indicum, the cultivated type, originated in India.[7][5] It tolerates drought conditions well, growing where other crops fail.[8][9] Sesame has one of the highest oil contents of any seed. With a rich, nutty flavor, it is a common ingredient in cuisines around the world.[10][11] Like other foods, it can trigger allergic reactions in some people and is one of the nine most common allergens outlined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[12][13]

Etymology

The word "sesame" is from Latin sesamum and Greek σήσαμον: sēsamon; which in turn are derived from ancient Semitic languages, e.g., Akkadian šamaššamu.[14] From these roots, words with the generalized meaning "oil, liquid fat" were derived.[15][16]

The word "benne" was first recorded to be used in English in 1769 and comes from Gullah benne which itself derives from Malinke bĕne.[17][4]

Origins and history

Sesame seed is considered to be the oldest oilseed crop known to humanity.[8] The genus has many species, and most are wild.[5] Most wild species of the genus Sesamum are native to sub-Saharan Africa.[5] S. indicum, the cultivated type,[7][18] originated in India.[15][19][5]

Archaeological remnants of charred sesame dating to about 3500-3050 BCE suggest sesame was domesticated in the Indian subcontinent at least 5500 years ago.[20][21] It has been claimed that trading of sesame between Mesopotamia and the Indian subcontinent occurred by 2000 BC.[22] It is possible that the Indus Valley civilization exported sesame oil to Mesopotamia, where it was known as ilu in Sumerian and ellu in Akkadian, compare Southern Dravidian Kannada eḷḷu, Tamil eḷ.[23]

Some reports claim sesame was cultivated in Egypt during the Ptolemaic period,[24] while others suggest the New Kingdom.[25][26] Egyptians called it sesemt, and it is included in the list of medicinal drugs in the scrolls of the Ebers Papyrus dated to be over 3600 years old. Excavations of King Tutankhamen uncovered baskets of sesame among other grave goods, suggesting that sesame was present in Egypt by 1350 BC.[27] Archeological reports indicate that sesame was grown and pressed to extract oil at least 2750 years ago in the empire of Urartu.[11][28][29] Others believe it may have originated in Ethiopia.[30]

Historically, sesame was favored for its ability to grow in areas that do not support the growth of other crops. It is also a robust crop that needs little farming support—it grows in drought conditions, in high heat, with residual moisture in soil after monsoons are gone or even when rains fail or when rains are excessive. It was a crop that could be grown by subsistence farmers at the edge of deserts, where no other crops grow. Sesame has been called a survivor crop.[9]

Botany

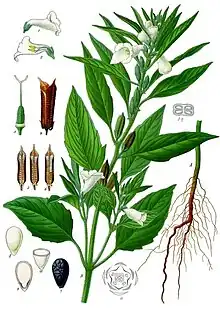

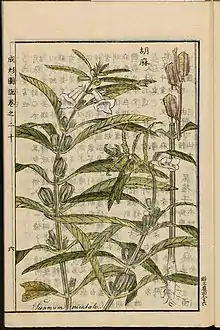

Sesame is a perennial plant growing 50 to 100 cm (1 ft 8 in to 3 ft 3 in) tall, with opposite leaves 4 to 14 cm (2 to 6 in) long with an entire margin; they are broad lanceolate, to 5 cm (2 in) broad, at the base of the plant, narrowing to just 1 cm (13⁄32 in) broad on the flowering stem. The flowers are tubular, 3 to 5 cm (1+1⁄8 to 2 in) long, with a four-lobed mouth. The flowers may vary in colour, with some being white, blue, or purple.

Sesame seeds occur in many colours depending on the cultivar. The most traded variety of sesame is off-white coloured. Other common colours are buff, tan, gold, brown, reddish, gray, and black. The colour is the same for the hull and the fruit.

Sesame fruit is a capsule, normally pubescent, rectangular in section, and typically grooved with a short, triangular beak. The length of the fruit capsule varies from 2 to 8 centimetres (3⁄4 to 3+1⁄8 in), its width varies between 0.5 and 2.0 centimetres (13⁄64 and 25⁄32 in), and the number of loculi varies from four to 12. The fruit naturally splits open (dehisces) to release the seeds by splitting along the septa from top to bottom or by means of two apical pores, depending on the varietal cultivar. The degree of dehiscence is of importance in breeding for mechanised harvesting, as is the insertion height of the first capsule.

Sesame seeds are small. Their sizes vary with the thousands of varieties known. Typically, the seeds are about 3 to 4 mm long by 2 mm wide and 1 mm thick (15⁄128 to 5⁄32 × 5⁄64 × 5⁄128). The seeds are ovate, slightly flattened, and somewhat thinner at the eye of the seed (hilum) than at the opposite end. The mass of 100 seeds is 0.203 g.[31] The seed coat (testa) may be smooth or ribbed.

Cultivation

Sesame varieties have adapted to many soil types. The high-yielding crops thrive best on well-drained, fertile soils of medium texture and neutral pH. However, these have a low tolerance for soils with high salt and water-logged conditions. Commercial sesame crops require 90 to 120 frost-free days. Warm conditions above 23 °C (73 °F) favor growth and yields. While sesame crops can grow in poor soils, the best yields come from properly fertilized farms.[11][32]

Initiation of flowering is sensitive to photoperiod and sesame variety. The photoperiod also affects the oil content in sesame seed; increased photoperiod increases oil content. The oil content of the seed is inversely proportional to its protein content.[11]

Sesame is drought-tolerant, in part due to its extensive root system. However, it requires adequate moisture for germination and early growth. While the crop survives drought and the presence of excess water, the yields are significantly lower in either condition. Moisture levels before planting and flowering impact yield most.[11]

Most commercial cultivars of sesame are intolerant of water-logging. Rainfall late in the season prolongs growth and increases loss to dehiscence, when the seedpod shatters, scattering the seed. Wind can also cause shattering at harvest.[11]

Processing

Sesame seeds are protected by a capsule that bursts when the seeds are ripe. The time of this bursting, or "dehiscence", tends to vary, so farmers cut plants by hand and place them together in an upright position to continue ripening until all the capsules have opened. The discovery of an indehiscent mutant (analogous to nonshattering domestic grains) by Langham in 1943 began the work towards the development of a high-yielding, dehiscence-resistant variety. Although researchers have made significant progress in sesame breeding, harvest losses due to early dehiscence continue to limit domestic US production.[33] Agronomists in Israel are working on modern cultivars of sesame that can be harvested by mechanical means.[34]

Since sesame is a small, flat seed, it is difficult to dry it after harvest because the small seed makes the movement of air around the seed difficult. Therefore, the seeds need to be harvested as dry as possible and stored at 6% moisture or less. If the seed is too moist, it can quickly heat up and become rancid.[10]

After harvesting, the seeds are usually cleaned and hulled. In some countries, once the seeds have been hulled, they are passed through an electronic color-sorting machine that rejects any discolored seeds to ensure perfect color, because sesame seeds with consistent appearance are perceived to be of better quality by consumers, and sell for a higher price.

Immature or off-sized seeds are removed and used for sesame oil production.

Production and trade

| Sesame seed production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

| 1,525,104 | |

| 740,000 | |

| 710,000 | |

| 658,000 | |

| 490,000 | |

| Global | 6,803,824 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[6] | |

In 2020, world production of sesame seeds was 7 million metric tons (6,900,000 long tons; 7,700,000 short tons), led by Sudan, Myanmar, and Tanzania (table).[6]

The white and other lighter-coloured sesame seeds are common in Europe, the Americas, West Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. The black and darker-coloured sesame seeds are mostly produced in China and Southeast Asia.[35]

In the United States most sesame is raised by farmers under contract to Sesaco, which also supplies proprietary seed.[36][37]

Trade

Japan is the world's largest sesame importer. Sesame oil, particularly from roasted seed, is an important component of Japanese cooking and traditionally the principal use of the seed. China is the second-largest importer of sesame, mostly oil-grade. China exports lower-priced food-grade sesame seeds, particularly to Southeast Asia. Other major importers are United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Turkey, and France.

Sesame seed is a high-value cash crop. Prices have ranged between US$800 and 1,700 per metric ton (810 and 1,730/long ton) between 2008 and 2010.[38][39]

Sesame exports sell across a wide price range. Quality perception, particularly how the seed looks, is a major pricing factor. Most importers who supply ingredient distributors and oil processors only want to purchase scientifically treated, properly cleaned, washed, dried, colour-sorted, size-graded, and impurity-free seeds with a guaranteed minimum oil content (not less than 40%) packed according to international standards. Seeds that do not meet these quality standards are considered unfit for export and are consumed locally. In 2008, by volume, premium prices, and quality, the largest exporter was India, followed by Ethiopia and Myanmar.[10][40]

Nutritional information

| Nutritional value per 100 grams | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 573 kcal (2,400 kJ) |

23.4 | |

| Sugars | 0.3 |

| Dietary fiber | 11.8 |

49.7 | |

| Saturated | 7.0 |

| Monounsaturated | 18.8 |

| Polyunsaturated | 21.8 |

17.7 | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A | 9 IU |

| Thiamine (B1) | 69% 0.79 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 21% 0.25 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 30% 4.52 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 61% 0.79 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 24% 97 μg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.25 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 98% 975 mg |

| Iron | 112% 14.6 mg |

| Magnesium | 99% 351 mg |

| Phosphorus | 90% 629 mg |

| Potassium | 10% 468 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 11 mg |

| Zinc | 82% 7.8 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 4.7 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

In a 100 g (3.5 oz) amount, dried whole sesame seeds provide 573 kilocalories and are composed of 5% water, 23% carbohydrates (including 12% dietary fiber), 50% fat, and 18% protein. A typical serving would be a tablespoon (9 grams), so nutrient content and % Daily Value (%DV) per serving would be approximately one-tenth of what is shown in the table.

The byproduct that remains after oil extraction from sesame seeds, also called sesame oil meal, is rich in protein (35–50%) and is used as feed for poultry and livestock.[10][11][35]

As many seeds do, whole sesame seeds contain a significant amount of phytic acid, which is considered an antinutrient in that it binds to certain nutritional elements consumed at the same time, especially minerals, and prevents their absorption by carrying them along as they pass through the small intestine. Heating and cooking reduce the amount of the acid in the seeds.[42]

Health effects

A meta-analysis showed that sesame consumption produced small reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure;[43] another demonstrated improvement in fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c.[44] Sesame oil studies reported a reduction of oxidative stress markers and lipid peroxidation.[45]

Allergy

Sesame can trigger the same allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, as seen with other food allergens.[12] A cross-reactivity exists between sesame and peanuts, hazelnuts and almonds.[12][46] In addition to food products derived from sesame seeds, such as tahini and sesame oil, persons with sesame allergies are encouraged to be aware of foods that may contain sesame, such as baked goods.[12][46][47] In addition to food sources, individuals allergic to sesame have been warned that a variety of non-food sources may also trigger a reaction to sesame, including cosmetics and skin-care products.[47]

Prevalence of sesame allergy is on the order of 0.1-0.2%, but higher in countries in the Middle East and Asia where consumption is more common as part of traditional diets.[12] In the United States, sesame allergy possibly affects 1.5 million individuals.[48][49]

Canada requires sesame labeling as an allergen.[47] In the European Union, identifying the presence of sesame, along with 13 other foods, either as an ingredient or unintended contaminant in packaged food is compulsory.[50] In the United States, the "FASTER Act" was passed in April 2021, stipulating that labeling be mandatory,[13] to be in effect January 1, 2023, making it the ninth required food ingredient for which labeling is mandated within the United States.[51][52]

Chemical composition

Sesame seeds contain the lignans sesamolin, sesamin, pinoresinol, and lariciresinol.[53][54]

Contamination

Contamination by Salmonella, E.coli, pesticides, or other pathogens may occur in large batches of sesame seeds, such as in September 2020 when high levels of a common industrial compound, ethylene oxide, was found in a 250-tonne shipment of sesame seeds from India.[55][56] After detection in Belgium, recalls for dozens of products and stores were issued across the European Union, totaling some 50 countries.[55][56] Products with an organic certification were also affected by the contamination.[57] Regular governmental food inspection for sesame contamination, as for Salmonella and E. coli in tahini, hummus or seeds, has found that poor hygiene practices during processing are common sources and routes of contamination.[58]

Culinary use

Sesame seed is a common ingredient in various cuisines. It is used whole in cooking for its rich, nutty flavour. Sesame seeds are sometimes added to bread, including bagels and the tops of hamburger buns. They may be baked into crackers, often in the form of sticks. In Sicily and France, the seeds are eaten on bread (ficelle sésame, sesame thread). In Greece, the seeds are also used in cakes.

Fast-food restaurants use buns with tops sprinkled with sesame seeds. About 75% of Mexico's sesame crop is purchased by McDonald's[59] for use in their sesame seed buns worldwide.[60]

Sesame seed cookies called Benne wafers, both sweet and savory, are popular in places such as Charleston, South Carolina.[61] Sesame seeds, also called benne, are believed to have been brought into the 17th-century colonial America by enslaved West Africans.[62] The entirety of the sesame plant was used extensively in West African cuisine. The seeds were commonly used as a thickener in soups and puddings, or could be roasted and infused in water to produce a coffee-like drink.[27] Sesame oil made from the seeds could be used as a substitute for butter, finding use as a shortening for making cakes.[27] Moreover, the leaves on mature plants, which are rich in mucilage, can be used as a laxative as well as a treatment for dysentery and cholera.[63] After arriving in North America, the plant was grown by slaves to serve as a subsistence staple as a nutritional supplement to their weekly rations.[64] Since then, they have become part of various American cuisines.

In Caribbean cuisine, sugar and white sesame seeds are combined into a bar resembling peanut brittle and sold in stores and street corners, like Bahamian Benny cakes.[65]

In Asia, sesame seeds are sprinkled onto some sushi-style foods.[66] In Japan, whole seeds are found in many salads and baked snacks, and tan and black sesame seed varieties are roasted and used to make the flavouring gomashio. East Asian cuisines, such as Chinese cuisine, use sesame seeds and oil in some dishes, such as dim sum, sesame seed balls (Cantonese: jin deui), and the Vietnamese bánh rán. Sesame flavour (through oil and roasted or raw seeds) is also used to marinate meat and vegetables. Chefs in tempura restaurants blend sesame and cottonseed oil for deep-frying. Ground black sesame and rice forms an edible paste when mixed with water, called zhimahu, a Chinese dessert and breakfast dish.

Sesame, or simsim as it is known in East Africa, is used in African cuisine. In Togo, the seeds are a main soup ingredient and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in the north of Angola, wangila is a dish of ground sesame, often served with smoked fish or lobster.

Sesame seeds and oil are used extensively in India. In most parts of the country, sesame seeds mixed with heated jaggery, sugar, or palm sugar is made into balls and bars similar to peanut brittle or nut clusters and eaten as snacks. In Manipur, black sesame is used in the preparation of chikki and cold-pressed oil.

Sesame is a common ingredient in many Middle Eastern cuisines. Sesame seeds are made into a paste called tahini (used in various ways, including hummus bi tahini) and the Middle Eastern confection halvah. Ground and processed, the seed is also used in sweet confections. Sesame is also a common component of the Levantine spice mixture za'atar, popular throughout the Middle East.[67][68]

In Indian, Middle Eastern, and East Asian cuisines, popular confectionery are made from sesame mixed with honey or syrup and roasted into a sesame candy. In Japanese cuisine, goma-dofu is made from sesame paste and starch.

Mexican cuisine and Salvadoran cuisine refers to sesame seeds as ajonjolí. It is mainly used as a sauce additive, such as mole or adobo. It is often also used to sprinkle over artisan breads and baked in traditional form to coat the smooth dough, especially on whole-wheat flatbreads or artisan nutrition bars, such as alegrías.

Sesame oil is sometimes used as a cooking oil in different parts of the world, though different forms have different characteristics for high-temperature frying. The "toasted" form of the oil (as distinguished from the "cold-pressed" form) has a distinctive pleasant aroma and taste, and is used as table condiment in some regions.

Gallery

Magnified image of white sesame seeds

Magnified image of white sesame seeds Sesame seeds are commonly added to baked goods and creative confectionery

Sesame seeds are commonly added to baked goods and creative confectionery Rolled khao phan with black sesame seeds

Rolled khao phan with black sesame seeds Sesame seed breadsticks

Sesame seed breadsticks Sesame sweet cake

Sesame sweet cake.jpg.webp) Sesame seed ball confection

Sesame seed ball confection Til-patti – a sesame brittle-type confection from India

Til-patti – a sesame brittle-type confection from India Simit, koulouri, or gevrek, a ring-shaped bread coated with sesame seeds

Simit, koulouri, or gevrek, a ring-shaped bread coated with sesame seeds Sesame flower, Behbahan

Sesame flower, Behbahan Sesame flower in Behbahan

Sesame flower in Behbahan

In literature

In myths, the opening of the capsule releases the treasure of sesame seeds,[69] as applied in the story of "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves" when the phrase "Open sesame" magically opens a sealed cave. Upon ripening, sesame pods split, releasing a pop and possibly indicating the origin of this phrase.

Sesame seeds are used conceptually in Hindi literature, in the proverbs "til dharne ki jagah na hona", meaning a place so crowded that no room remains for a single seed of sesame, and "in tilon men tel nahin", referring to a person who appears to be useful, but is selfish when the time for need comes, literally meaning 'no oil (is left) in this sesame'.

See also

References

- "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species". Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "Definition of BENNE". Merriam Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- Bedigian, Dorothea (2015-01-02). "Systematics and evolution in Sesamum L. (Pedaliaceae), part 1: Evidence regarding the origin of sesame and its closest relatives". Webbia. University of Florence. 70 (1): 1–42. doi:10.1080/00837792.2014.968457. ISSN 0083-7792. S2CID 85002894.

- "Sesame seed production in 2018, Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity from pick lists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- T. Ogasawara; K. Chiba; M. Tada (1988). "Sesamum indicum L. (Sesame): In Vitro Culture, and the Production of Naphthoquinone and Other Secondary Metabolites". In Y. P. S. Bajaj (ed.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants X. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-62727-2.

- Raghav Ram; David Catlin; Juan Romero & Craig Cowley (1990). "Sesame: New Approaches for Crop Improvement". Purdue University.

- D. Ray Langham. "Phenology of Sesame" (PDF). American Sesame Growers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-28.

- Ray Hansen; Diane Huntrods (August 2011) [2005]. "Sesame profile". Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2016-01-21.

- E.S. Oplinger; D.H. Putnam; et al. "Sesame". Purdue University.

- Adatia, A; Clarke, AE; Yanishevsky, Y; Ben-Shoshan, M (2017). "Sesame allergy: current perspectives (Review)". Journal of Asthma and Allergy. 10: 141–151. doi:10.2147/JAA.S113612. ISSN 1178-6965. PMC 5414576. PMID 28490893.

- "Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research Act of 2021 or the FASTER Act of 2021". Congress.gov. 4 April 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Definition: Teel, Sesame". Merriam-Webster. 15 October 2023.

- Bedigian, Dorothea, ed. (2010). Sesame: The genus Sesamum. CRC Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-4200-0520-2. ISBN 978-0-8493-3538-9.

- "Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)". Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages.

- Sarah Bryan (2015). "Benne for Good Luck". North Carolina Folklife Institute. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- Proceedings of the Harlan Symposium 1997- The Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2012-06-17

- Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria (2000). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-19-850357-6.

- Bedigian, Dorothea; Harlan, Jack R. (1986). "Evidence for Cultivation of Sesame in the Ancient World". Economic Botany. 40 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1007/BF02859136. ISSN 0013-0001. JSTOR 4254846. S2CID 24408335.

- E.S. Oplinger; D.H. Putnam; et al. "Sesame". Purdue University.

- Fuller, D.Q. (2003). "Further Evidence on the Prehistory of Sesame" (PDF). Asian Agri-History. 7 (2): 127–137.

- Martha, T. Roth (1958). The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD) Volume 4, E. Chicago. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-91-898610-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Serpico M; White R (2000). P T Nicholson; I Shaw (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45257-1.

- David, Ann Rosalie (1999). Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-19-513215-1.

- Voeks, Robert; Rashford, John (2013). African Ethnobotany in the Americas. Springer, New York. pp. 67–123.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sesame Coordinators. "Sesame". Sesaco. Archived from the original on 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- Frederic Rosengarten (2004). The Book of Edible Nuts. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43499-5.

- Peter, K.V. (2012). Handbook of herbs and spices Volume 2. p. 449.

- Tunde-Akintunde, T. Y.; Akintunde, B. O. (2004-05-01). "Some Physical Properties of Sesame Seed". Biosystems Engineering. 88 (1): 127–129. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2004.01.009. ISSN 1537-5110.

- TJAI (2002). "Sesame: high value oilseed" (PDF). Thomas Jefferson Agriculture Institute.

- E.S. Oplinger; D.H. Putnam; A.R. Kaminski; C.V. Hanson; E.A. Oelke; E.E. Schulte & J.D. Doll (1990). "Sesame". Alternative Field Crops Manual, the University of Wisconsin and University of Minnesota.

- Ronit Vered (22 July 2022). "A Global Sesame Shortage Puts Tahini in Peril. Can Israel Save It?". Haaretz. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "Sesame (Sesamum indicum) seeds and oil meal | Feedipedia". www.feedipedia.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- Latzke, Jennifer M. "Tiny sesame seed offers big returns for Southern Plains growers". www.hpj.com. High Plains Journal. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- "Sesame Profile". www.agmrc.org. Agriculture Marketing Research Center. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- "Oil seed prices and futures". Commodity Prices. July 2010.

- Mal Bennett. "Sesame" (PDF). Ag Market Research Center.

- "Sesame Export Statistics". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011.

- "Seeds, sesame seeds, whole, dried". USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Bohn, L.; Meyer, A. S.; Rasmussen, S. K. (2008). "Phytate: Impact on environment and human nutrition. A challenge for molecular breeding". Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B. 9 (3): 165–191. doi:10.1631/jzus.B0710640. PMC 2266880. PMID 18357620.

- Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Nikbakht E, Natanelov E, Khalesi S (2017). "Can sesame consumption improve blood pressure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 97 (10): 3087–94. Bibcode:2017JSFA...97.3087K. doi:10.1002/jsfa.8361. PMID 28387047.

- Sohouli MH, Haghshenas N, Hernández-Ruiz Á, Shidfar F (January 2022). "Consumption of sesame seeds and sesame products has favorable effects on blood glucose levels but not on insulin resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials". Phytother Res. 36 (3): 1126–1134. doi:10.1002/ptr.7379. PMID 35043479. S2CID 246034854.

- Gouveia Lde A, Cardoso CA, de Oliveira GM, Rosa G, Moreira AS (2016). "Effects of the Intake of Sesame Seeds (Sesamum indicum L.) and Derivatives on Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Review". Journal of Medicinal Food. 19 (4): 337–45. doi:10.1089/jmf.2015.0075. PMID 27074618.

- "Sesame seed allergy and cross-reactivity". VeryWell Health. 4 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Sesame - A priority food allergen". Health Canada, Government of Canada. 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Minali Nigam (5 August 2019). "1.5 million people in the US might have sesame allergies". CNN. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Sicherer SH, Muñoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA (June 2010). "US prevalence of peanut and sesame allergy". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 125 (6): 1322–26. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.029. PMID 20462634.

- "Regulation (EG) 1169/2011 (Annex II)". Eur-Lex - European Union Law, European Union. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Sesame Allergy". FARE. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Sesame Allergy and Food Labels". Allergy & Asthma Network. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Milder, Ivon E. J.; Arts, Ilja C. W.; Betty; Venema, Dini P.; Hollman, Peter C. H. (2005). "Lignan contents of Dutch plant foods: a database including lariciresinol, pinoresinol, secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol". British Journal of Nutrition. 93 (3): 393–402. doi:10.1079/BJN20051371. PMID 15877880.

- Kuo PC, Lin MC, Chen GF, Yiu TJ, Tzen JT (2011). "Identification of methanol-soluble compounds in sesame and evaluation of antioxidant potential of its lignans". J Agric Food Chem. 59 (7): 3214–9. doi:10.1021/jf104311g. PMID 21391595.

- Joe Whitworth (30 October 2020). "EU toughens rules for sesame seeds from India". Food Safety News.

- Hannah Thompson (4 November 2020). "France recalls sesame seed products due to toxic pesticide". The Connexion. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "Recall of Organic Sesame Seeds and Organic Omega Seed Mix From The Source Bulk Foods, Rathmines, Due to the Presence of the Unauthorised Pesticide Ethylene Oxide". www.fsai.ie.

- "2011-2012 Salmonella and generic E. coli in tahini and sesame seeds". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Laino, Charlene (March 16, 2009). "Sesame Seed Allergy Now Among Most Common Food Allergies". WebMD Health News. Washington, DC.

- "McDonald's Now Exporting from Mexico". The Toledo Blade. Reuters. October 27, 1992.

- "Olde Colony Bakery". Olde Colony Bakery. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- "Benne Wafers". www.kingarthurbaking.com. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- Bedigian, Dorothea (2013). African Origins of Sesame Cultivation in the Americas. Springer, New York, NY.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Carney, Judith; Rosomoff, Richard (2009). In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. pp. 123–138.

- BodineVictoria (2020-08-10). "Bahamian Benny Cake". BodineVictoria. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- "Third-culture breakfast: Asia-inspired morning feasts from Hetty McKinnon". the Guardian. 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- "Inside the Spice Cabinet: Za'atar Seasoning Blend". Kitchn.

- "Make Your Own Za'atar Spice Mix and Kick the Flavor Up a Notch". The Spruce Eats.

- Peter Griffee. "Sesamum indicum L." Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Further reading

- Bedigian, Dorothea; Harlan, Jack R. (April–June 1986). "Evidence for Cultivation of Sesame in the Ancient World". Economic Botany. 40 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1007/BF02859136. JSTOR 4254846. S2CID 24408335.

External links

Data related to Sesamum indicum at Wikispecies

Data related to Sesamum indicum at Wikispecies