Sevnica

Sevnica (pronounced [ˈséːwnitsa] ⓘ; German: Lichtenwald[2]) is a town on the left bank of the Sava River in central Slovenia. It is the seat of the Municipality of Sevnica. It is one of the three major settlements in the Lower Sava Valley. The old town of Sevnica lies beneath Sevnica Castle, which is perched on top of Castle Hill, while the new part of town stretches along the plain among the hills up the Sava Valley, forming another town core at the confluence of the Sevnična and Sava rivers.[3]

Sevnica | |

|---|---|

| |

Coat of arms | |

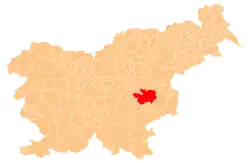

Sevnica Location in Slovenia | |

| Coordinates: 46°0′33.17″N 15°18′14.74″E | |

| Country | |

| Traditional region | Styria |

| Statistical region | Lower Sava |

| Municipality | Sevnica |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.0 km2 (1.9 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 183.1 m (600.7 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 4,993 |

| Vehicle registration | KK |

| Climate | Cfb |

| [1] | |

Name

The settlement was first attested in written records in 1275 in German as Liechtenwalde (and as Lihtenwalde in 1309, Lietenueld in 1344, Liechtenwald in 1347, and Sielnizza in 1581). The Slovene name is probably derived from a hydronym referring to Sevnična Creek (first attested in 1488 as Zellnitz). This name is derived from the adjective *se(d)lьnъ 'belonging to a settlement, village'. The Slovene name is not connected to the German name, which refers to deciduous woods.[4] In the past the German name of the town was Lichtenwald.[2]

History

For centuries, the town of Sevnica was situated on the border of two historical regions of the Habsburg Empire: Carniola and Styria. It was first mentioned in written documents dating to 1275 by its German name Lichtenwalde. At that time, it was one of the most important settlements along the lower Sava. Throughout the High and Late Middle Ages, it was an exclave of the Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg. It was seized by the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I in 1490, as a retaliation for the Archbishop's alliance with Matthias Corvinus in the war waged against the Habsburgs. Thereafter, it was incorporated in the Duchy of Styria until 1918.

In 1322 it acquired the status of a market town, with extended market rights in 1513. Between the 14th and 17th centuries, it suffered greatly from frequent Ottoman raids and never fully recovered its previous wealth. In the 16th century it was an important center of Protestant reformation in the Slovene Lands; the Slovene Lutheran author Jurij Dalmatin also preached in the town.

Between 1809 and 1813, it was a border town between the French-administered Illyrian Provinces and the Austrian Empire. In the mid-19th century, it became an important center of the Slovene national revival; in 1869, it hosted one of the first mass rallies in favor of a United Slovenia.

In 1862 it received a railway connection, which boosted the local economy. In 1938 railway from Sevnica to Trebnje was completed.

During World War II, when the area was annexed by Nazi Germany, the majority of its Slovene inhabitants were expelled and replaced by ethnic Germans resettled from Gottschee County.[5][6][7] Many locals died in Nazi concentration camps. After the war, the town started developing as an industrial center in the newly named Lower Sava Valley.

Mass graves

Sevnica is the site of four known mass graves associated with the Second World War. Three of them contain the remains of undetermined victims. The Vrtača Mass Grave (Slovene: Grobišče Vrtača) is located in the woods 50 meters (160 ft) west of the hamlet of Vrtača.[8] The Florian Street Mass Grave (Grobišče ob Florjanski ulici) is located on the north edge of a large field next to a small woods.[9] The Hraste Mass Grave (Grobišče na Hrastah) is located among the vineyards above the houses on Trubar Street (Trubarjeva ulica).[10] The Dobrava Mass Grave (Grobišče pod Dobravo) is located in a thicket 15 meters (49 ft) north of the house at Trubar Street no. 7. It contains the remains of German soldiers.[11]

Church

The parish church in the town is dedicated to Saint Nicholas and belongs to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Celje. It was built in 1862 on the site of a 15th-century building.[12] Other churches in town are dedicated to Saint Florian,[13] the Mother of God[14] and Saint Anne,[15] all belonging to the same parish.

Economy

The company Lisca, one of the largest lingerie companies in Europe, is based in Sevnica. Another important company is the furniture manufacturing company Stilles.

Notable people

Notable people that were born or lived in Sevnica include:

- Fridolin Kaučič (sl) (1859–1922), biographer[16][17]

- Anton Jurij Luby (1749–1802), theology professor[16][18]

- Danimir Kerin (born 1922), chemist[16][19]

- Josip Mešiček (1865–1923), composer[16][20]

- Alojzij Praunseis (1868–1934), physician[16][21]

- Avgusta Smolej (born 1915), poet and translator[16][22]

- Marta Šribar (1924–1988), sculptor[16][23][24]

- Melania Trump (born 1970), former model, First Lady of the United States (2017–2021)[25]

- Jakob Žmavc (sl) (1867–1957), historian and geographer[16][26]

References

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia

- Leksikon občin kraljestev in dežel zastopanih v državnem zboru, vol. 4: Štajersko. 1904. Vienna: C. Kr. Dvorna in Državna Tiskarna, p. 20.

- Sevnica municipal site

- Snoj, Marko (2009). Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Ljubljana: Modrijan. p. 374.

- Ferenc, Tone (1995). "Posavje". Enciklopedija Slovenije. Vol. 9. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga. p. 156.

- Čepič, Zdenko; Guštin, Damijan; Vončina, Dejan (2005). Podobe iz življenja Slovencev v drugi svetovni vojni. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga. p. 57.

- Ferenc, Tone (1968). Nacisticka politika denacionalizacije u Sloveniji u godinama od 1941 do 1945. Ljubljana: Partizanska knjiga. p. 554.

- Ferenc, Mitja (December 2009). "Grobišče Vrtača". Geopedia (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Služba za vojna grobišča, Ministrstvo za delo, družino in socialne zadeve. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Ferenc, Mitja (December 2009). "Grobišče ob Florjanski ulici". Geopedia (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Služba za vojna grobišča, Ministrstvo za delo, družino in socialne zadeve. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Ferenc, Mitja (December 2009). "Grobišče na Hrastah". Geopedia (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Služba za vojna grobišča, Ministrstvo za delo, družino in socialne zadeve. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Ferenc, Mitja (December 2009). "Grobišče pod Dobravo". Geopedia (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Služba za vojna grobišča, Ministrstvo za delo, družino in socialne zadeve. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- "EŠD 3346". Registry of Immovable Cultural Heritage (in Slovenian). Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- "EŠD 3347". Registry of Immovable Cultural Heritage (in Slovenian). Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- "EŠD 3349". Registry of Immovable Cultural Heritage (in Slovenian). Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- "EŠD 3350". Registry of Immovable Cultural Heritage (in Slovenian). Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- Savnik, Roman (1976). Krajevni leksikon Slovenije, vol. 3. Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije. pp. 273–275.

- Slovenski biografski leksikon: Kaučič Fridolin. (in Slovene)

- Slovenski biografski leksikon: Luby Anton Jurij. (in Slovene)

- Adamič, France. 1991. "Kerin Danimir." Enciklopedija Slovenije, vol. 5, p. 53. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga.

- Slovenski biografski leksikon: Mešiček Josip. (in Slovene)

- Slovenski biografski leksikon: Praunseis Alojzij. (in Slovene)

- Moder, Janko. 1985. Slovenski leksikon novejšega prevajanja. Koper: Lipa, p. 277.

- Krek, Marija. 1970. Oblikovanje v Jugoslaviji 1. Belgrade: Savez likovnih umetnika primenjenih umetnosti Jugoslavije.

- Domljan, Žarko. 1995. Enciklopedija hrvatske umjetnosti, vol. 2. Zagreb: Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, p. 332.

- Biography of Melania Trump, StarPulse Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Slovenski biografski leksikon: Žmavc Jakob. (in Slovene)

External links

Media related to Sevnica at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sevnica at Wikimedia Commons- Sevnica on Geopedia