Sex worker

A sex worker is a person who provides sex work, either on a regular or occasional basis.[1] The term is used in reference to those who work in all areas of the sex industry.[2][3]

_(1).jpg.webp)

According to one view, sex work is different from sexual exploitation, or the forcing of a person to commit sexual acts, in that sex work is voluntary "and is seen as the commercial exchange of sex for money or goods".[4]

Terminology

The term "sex worker" was coined in 1978 by sex worker activist Carol Leigh.[5] Its use became popularized after publication of the anthology, Sex Work: Writings By Women In The Sex Industry in 1987, edited by Frédérique Delacoste and Priscilla Alexander.[6][7][8] The term "sex worker" has since spread into much wider use, including in academic publications, by NGOs and labor unions, and by governmental and intergovernmental agencies, such as the World Health Organization.[9] The term is listed in the Oxford English Dictionary[2] and Merriam-Webster's Dictionary.[10]

The term "sex worker" is used by some types of sex workers (i.e. prostitutes) to avoid invoking the stigma associated with the word "prostitute". Using the term "sex worker" rather than "prostitute" also allows more members of the sex industry to be represented and helps ensure that individuals who are actually prostitutes are not singled out and associated with the negative connotations of "prostitute". In addition, choosing to use the term "sex worker" rather than "prostitute" shows ownership over the individuals' career choices. Some argue that those who prefer the term "sex worker" wish to separate their occupation from their person. Describing someone as a sex worker recognizes that the individual may have many different facets, and are not necessarily defined by their job.

The term is strongly opposed, however, by many who are morally opposed to the sex industry, such as social conservatives, anti-prostitution feminists, and other prohibitionists.[11][12] Such groups view prostitution variously as a crime or as victimization, and see the term "sex work" as legitimizing criminal activity or exploitation as a type of labor.[13][14]

In practice

Sex work can take the form of prostitution, stripping or lap dancing, performance in pornography, phone or internet sex, or any other exchange of sexual services for financial or material gain. Sex workers who include sexual intercourse as part of their services are considered full-service sex workers.[15] The variety in the tasks encompassed by sex work leads to a large range in both severity and nature of risks that sex workers face in their occupations. Sex workers can act independently as individuals, work for a company or corporation, or work as part of a brothel. All of the above can be undertaken either by free choice or by coercion, or, as some argue, along a continuum between conflict and agency.[16] Sex workers may also be hired to be companions on a trip or to perform sexual services within the context of a trip; either of these can be voluntary or forced labor.[17]

Motivations

Sex workers may be any gender and exchange sexual services or favors for money or other gifts.[18] The motives of sex workers vary widely and can include debt, coercion, survival, or simply as a way to earn a living.[19] Sexual empowerment is another possible reason why people engage in sex work. One Canadian study found that a quarter of the sex workers interviewed started sex work because they found it "appealing".[20] The flexibility to choose hours of work and the ability to select one's own client base may also contribute to the appeal of sex work when compared to other service industry jobs.[20] Sex work may also be a way to fund addiction.[21] This line of work can be fueled by an individual's addiction to illegal substances before entering the industry or being introduced to these substances after entering the industry.[21] These motives also align with varying climates surrounding sex work in different communities and cultures. In some cases, sex work is linked to tourism.

Demographics

Transgender people are more likely than the general population to do sex work, particularly trans women and trans people of color.[22] In a study of female Indian sex workers, illiteracy and lower social status were more prevalent than among the general female population.[23]

One study of sex work in Tijuana, Mexico, found that the majority of sex workers there are young, female, and heterosexual.[24] Many of these studies attempt to use smaller samples of sex workers and pimps in order to extrapolate about larger populations of sex workers. One report on the underground sex trade in the United States used known data on the illegal drug and weapon trades and interviews with sex workers and pimps in order to draw conclusions about the number of sex workers in eight American cities.[25] However, studies like this one can come under scrutiny for a perceived emphasis on the activities and perspectives of pimps and other sex work managers rather than those of sex work providers themselves. Another criticism is that sex trafficking may not be adequately assessed in relation to sex work in these studies.[26]

Many studies struggle to gain demographic information about the prevalence of sex work, as many countries or cities have laws prohibiting prostitution or other sex work. In addition, sex trafficking, or forced sex work, is also difficult to quantify due to its underground and covert nature. In addition, finding a representative sample of sex workers in a given city can be nearly impossible because the size of the population itself is unknown. Maintaining privacy and confidentiality in research is also difficult because many sex workers may face prosecution and other consequences if their identities are revealed.[27]

Discrimination

Sex workers may be stereotyped as deviant, hypersexual, sexually risky, and substance abusive. Sex workers may cope with this stigmatization in ways such as hiding their occupation from non-sex workers, social withdrawal, and creating a false self to perform at work.[28] Sex-work-related stigma may help perpetuate rape culture and can lead to slut-shaming.[29][30]

Sex work is also often conflated with sex trafficking, despite the fact that some sex workers choose to consensually engage in the sex trade. For example, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act in the United States was passed to ostensibly protect victims of sex trafficking but included language making it illegal to advertise consensual sex online. Such laws have a significantly negative impact on sex workers.[18]

Globally, sex workers encounter barriers in accessing health care, legislation, legal resources, and labor rights. In a study of U.S sex workers, 43% of interview participants reported exposure to intimate-partner violence, physical violence, armed physical violence, and sexual violence in the forms of sexual coercion and rape.[31] In this same study, a sex worker reported, "in this lifestyle, nothing's safe".[31] Sex workers may experience police abuse as well, as the police may use their authority to intimidate sex workers. Police officers in some countries have been reported to exploit street-based sex workers' fear of incarceration to force them to have sex with the police without payment, sometimes still arresting them after having coerced sex.[31] Police may also compromise sex workers' safety, often holding sex workers responsible for crimes perpetrated against them because of the stigma attached to their occupation.[32] There is growth in advocacy organizations to reduce and erase prejudice and stigma against sex work, and to provide more support and resources for sex workers.[33]

Legal dimensions of sex work

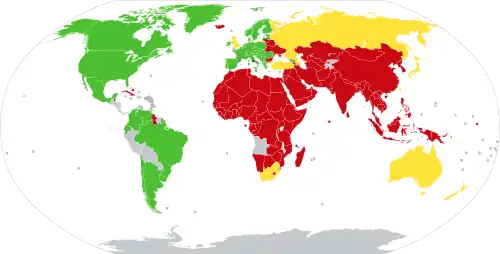

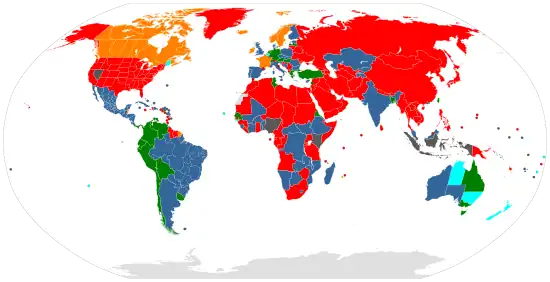

Depending on local law, sex workers' activities may be regulated, controlled, tolerated, or prohibited. In most countries, even those where sex work is legal, sex workers may be stigmatized and marginalized, which may prevent them from seeking legal redress for discrimination (e.g., racial discrimination by a strip club owner), non-payment by a client, assault or rape. Sex worker advocates have identified this as whorephobia.[34][35]

The legality of different types of sex work varies within and between regions of the world. For example, while pornography is legal in the United States, prostitution is illegal in most parts of the US. However, in other regions of the world, both pornography and prostitution are illegal; in others, both are legal. One example of a country in which pornography, prostitution, and all professions encompassed under the umbrella of sex work are all legal is New Zealand. Under the Prostitution Reform Act of New Zealand, laws and regulations have been put into place in order to ensure the safety and protection of its sex workers. For example, since the implementation of the Prostitution Reform Act, "any person seeking to open a larger brothel, where more than four sex workers will be working requires a Brothel Operators Certificate, which certifies them as a suitable person to exercise control over sex workers in the workplace. [In addition,] sex workers operating in managed premises have access to labour rights and human rights protection and can pursue claims before the courts, like any other worker or employee."[36] In regions where sex work is illegal, advocates for sex workers' rights argue that the covert nature of illegal prostitution is a barrier to access to legal resources.[37] However, some who oppose the legalization of prostitution argue that sex work is inherently exploitative and can never be legalized or practiced in a way that respects the rights of those who perform it.[38]

There are many arguments against legalizing prostitution/sex work. In one study, women involved in sex work were interviewed and asked if they thought it should be made legal. They answered that they thought it should not, as it would put women at higher risk from violent customers if it were considered legitimate work, and they would not want their friends or family entering the sex industry to earn money. Another argument is that legalizing sex work would increase the demand for it, and women should not be treated as sexual merchandise. A study showed that in countries that have legalized prostitution, there was an increase in human trafficking.[39] The studies also showed that legalizing sex work led to an increase in sex trafficking, which is another reason people give for making sex work illegal.[40] An argument against legalizing sex work is to keep children from being involved in this industry. Children who have been exploited suffer long-term negative consequences.[41]

There are also arguments for legalizing prostitution/sex work. One major argument for legalizing prostitution is that women should have a right to do what they want with their own bodies. The government should not have a say in what they do for work, and if they want to sell their bodies it is their own decision. Another common argument for legalizing prostitution is that enforcing prostitution laws is a waste of money. Some believe prostitution will continue to persist despite whatever laws and regulations are implemented against it. In arguing for the decriminalization of sex work, the Minister of Justice of the Netherlands expanded upon this argument in court when stating that, "prostitution has existed for a long time and will continue to do so…Prohibition is not the way to proceed…One should allow for voluntary prostitution. The authorities can then regulate prostitution, [and] it can become healthy, safe, transparent, and cleansed from criminal side-effects."[42] People who wish to legalize prostitution do not see enforcing laws against sex work as effective and think the money is better spent elsewhere. Many people also argue that legalization of prostitution will lead to less harm for the sex workers. They argue that the decriminalization of sex work will decrease the exploitation of sex workers by third parties such as pimps and managers. A final argument for the legalization of sex work is that prostitution laws are unconstitutional. Some argue that these laws go against people's rights to free speech and privacy.[43]

Risk reduction

Risk reduction in sex work is a highly debated topic. "Abolitionism" and "nonabolitionism" or "empowerment" are regarded as opposing ways in which risk reduction is approached.[44] While abolitionism would call for an end to all sex work, empowerment would encourage the formation of networks among sex workers and enable them to prevent STIs and other health risks by communicating with each other.[45] Both approaches aim to reduce rates of disease and other negative effects of sex work.

In addition, sex workers themselves have disputed the dichotomous nature of abolitionism and nonabolitionism, advocating instead a focus on sex workers' rights. In 1999, the Network of Sex Worker Projects claimed that "Historically, anti-trafficking measures have been more concerned with protecting 'innocent' women from becoming prostitutes than with ensuring the human rights of those in the sex industry.[44] Penelope Saunders, a sex workers' rights advocate, claims that the sex workers' rights approach considers more of the historical context of sex work than either abolitionism or empowerment. In addition, Jo Doezema has written that the dichotomy of the voluntary and forced approaches to sex work has served to deny sex workers agency.[46]

Health

Sex workers are unlikely to disclose their work to healthcare providers. This can be due to embarrassment, fear of disapproval, or a disbelief that sex work can have effects on their health.[47] The criminalization of sex work in many places can also lead to a reluctance to disclose for fear of being turned in for illegal activities. There are very few legal protections for sex workers due to criminalization; thus, in many cases, a sex worker reporting violence to a healthcare provider may not be able to take legal action against their aggressor.[48]

Health risks of sex work relate primarily to sexually transmitted infections and to drug use. In one study, nearly 40% of sex workers who visited a health center reported illegal drug use.[47] In general, transgender women sex workers have a higher risk of contracting HIV than cisgender male and female sex workers and transgender women who are not sex workers.[49]

The reason transgender women are at higher risk for developing HIV is their combination of risk factors. They face biological, personal, relational, and structural risks that all increase their chances of getting HIV. Biological factors include incorrect condom usage because of erectile dysfunction from hormones taken to become more feminine and receptive anal intercourse without a condom which is a high risk for developing HIV. Personal factors include mental health issues that lead to increased sexual risk, such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse provoked through lack of support, violence, etc. Structural risks include involvement in sex work being linked to poverty, substance abuse, and other factors that are more prevalent in transgender women based on their tendency to be socially marginalized and not accepted for challenging gender norms. The largest risk for HIV is unprotected sex with male partners, and studies have been emerging that show men who have sex with transgender women are more likely to use drugs than men that do not.[50]

Condom use is one way to mitigate the risk of contracting an STI. However, negotiating condom use with one's clients and partners is often an obstacle to practicing safer sex. While there is not much data on rates of violence against sex workers, many sex workers do not use condoms due to the fear of resistance and violence from clients. Some countries also have laws prohibiting condom possession; this reduces the likelihood that sex workers will use condoms.[48] Increased organization and networking among sex workers has been shown to increase condom use by increasing access to and education about STI prevention. Brothels with strong workplace health practices, including the availability of condoms, have also increased condom use among their workers.[48]

Health concerns of exotic dancers

In order to protect themselves from the stigma of sex work, many dancers resort to othering themselves. Othering involves constructing oneself as superior to one's peers, and the dancer persona provides an internal boundary that separates the "authentic" from the stripper self. This practice creates a significant amount of stress for the dancers, in turn leading many to resort to using drugs and alcohol to cope. Since it is so widespread, the use of drugs has become normalized in the exotic dance scene.

Despite this normalization, passing as nonusers, or covering as users of less maligned drugs, is necessary. This is because strippers concurrently attribute a strong moral constitution to those that resist the drug atmosphere; it is a testament to personal strength and willpower. It is also an occasion for dancers to "other" fellow strippers. Valorizing resistance to the drug space discursively positions "good" strippers against such a drug locale and indicates why dancers are motivated to closet hard drug use.

Stigma causes strippers to hide their lifestyles from friends and family alienating themselves from a support system. Further, the stress of trying to hide their lifestyles from others due to fear of scrutiny affects the mental health of dancers.[51][52]

Forced sex work

Forced sex work is when an individual enters into any sex trade due to coercion rather than by choice. Forced sex work increases the likelihood that a sex worker will contract HIV/AIDS or another sexually transmitted infection, particularly when an individual enters sex work before the age of 18.[53] In addition, even when sex workers do consent to certain sex acts, they are often forced or coerced into others (often anal intercourse) by clients. Sex workers may also experience strong resistance to condom use by their clients, which may extend into a lack of consent by the worker to any sexual act performed in the encounter; this risk is magnified when sex workers are trafficked or forced into sex work.[48][54]

Forced sex work often involves deception - workers are told that they can make a living and are then not allowed to leave. This deception can cause ill effects on the mental health of many sex workers. In addition, an assessment of studies estimates that between 40% and 70% of sex workers face violence within a year.[48] Currently, there is little support for migrant workers in many countries, including those who have been trafficked to a location for sex.[55]

Advocacy

Sex worker's rights advocates argue that sex workers should have the same basic human and labor rights as other working people.[43] For example, the Canadian Guild for Erotic Labour calls for the legalization of sex work, the elimination of state regulations that are more repressive than those imposed on other workers and businesses, the right to recognition and protection under labour and employment laws, the right to form and join professional associations or unions, and the right to legally cross borders to work. Advocates also want to see changes in legal practices involving sex work, the Red Umbrella Project has pushed for the decriminalization of condoms and changes to New York's sex workers diversion program.[56] Advocacy for the interests of sex workers can come from a variety of sources, including non-governmental organizations, labor rights organizations, governments, or sex workers themselves. In Latin America and the Caribbean, sex worker advocacy dates back to the late 19th century in Havana, Cuba. A catalyst in the movement being a newspaper published by Havana sex workers. This publication went by the name La Cebolla, created by Las Horizontales.[57] Each year in London, The Sexual Freedom Awards is held to honor the most notable advocates and pioneers of sexual freedom and sex workers' rights in the UK, where sex work is essentially legal.

Unionization of sex work

The unionization of sex workers is a recent development. The first organization within the contemporary sex workers' rights movement was Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE), founded in 1973 in San Francisco, California. Many organizations in Western countries were established in the decade after the founding of COYOTE.[58] Currently, a small number of sex worker unions exist worldwide. One of the largest is the International Union of Sex Workers, headquartered in the United Kingdom. The IUSW advocates for the rights of all sex workers, whether they chose freely or were coerced to enter the trade, and promotes policies that benefit the interests of sex workers both in the UK and abroad.[59] Many regions are home to sex worker unions, including Latin America, Brazil, Canada, Europe, and Africa.[60]

In unionizing, many sex workers face issues relating to communication and to the legality of sex work. Because sex work is illegal in many places where they wish to organize, it is difficult to communicate with other sex workers in order to organize. There is also concern with the legitimacy of sex work as a career and an activity that merits formal organizing, largely because of the sexism often present in sex work and the devaluation of sex work as not comparable to other paid labor and employment.[58]

A factor affecting the unionization of sex work is that many sex workers belong to populations that historically have not had a strong representation in labor unions. While this unionization can be viewed as a way of empowering sex workers and granting them agency within their profession, it is also criticized as implicitly lending its approval to sexism and power imbalances already present in sex work. Unionization also implies a submission to or operation within the systems of capitalism, which is of concern to some feminists.[58]

Unionizing exotic dancers

Performers in general are problematic to categorize because they often exercise a high level of control over their work product, one characteristic of an independent contractor. Additionally, their work can be artistic in nature and often done on a freelance basis. Often, the work of performers does not possess the obvious attributes of employees such as regular working hours, places, or duties. Consequently, employers misclassify them because they are unsure of their workers' status, or they purposely misclassify them to take advantage of independent contractors' low costs. Exotic dance clubs are one such employer that purposely misclassifies their performers as independent contractors.

There are additional hurdles in terms of self-esteem and commitment to unionize. On the most basic level, dancers themselves must have the desire to unionize for collective action. For those who wish not to conform to group activity or want to remain independent, a union may seem as controlling as club management since joining a union would obligate them to pay dues and abide by decisions made through majority vote, with or without their personal approval.

In the Lusty Lady case study, this strip club was the first all-woman-managed club to successfully unionize in 1996. Some of the working conditions they were able to address included "protest[ing] racist hiring practices, customers being allowed to videotape dancers without their consent via one-way mirrors, inconsistent disciplinary policies, lack of health benefits, and an overall dearth of job security". Unionizing exotic dancers can certainly bring better work conditions and fair pay, but it is difficult to do at times because of their dubious employee categorization. Also, as is the case with many other unions, dancers are often reluctant to join them. This reluctance can be due to many factors, ranging from the cost of joining a union to the dancers believing they do not need union support because they will not be exotic dancers for a long enough period of time to justify joining a union.[61][62]

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

NGOs often play a large role in outreach to sex workers, particularly in HIV and STI prevention efforts.[63] However, NGO outreach to sex workers for HIV prevention is sometimes less coordinated and organized than similar HIV prevention programs targeted at different groups (such as men who have sex with men).[64] This lack of organization may be due to the legal status of prostitution and other sex work in the country in question; in China, many sex work and drug abuse NGOs do not formally register with the government and thus run many of their programs on a small scale and discreetly.[64]

While some NGOs have increased their programming to improve conditions within the context of sex work, these programs are criticized at times due to their failure to dismantle the oppressive structures of prostitution, particularly forced trafficking. Some scholars believe that advocating for rights within the institution of prostitution is not enough; rather, programs that seek to empower sex workers must empower them to leave sex work as well as improve their rights within the context of sex work.[65]

See also

References

- "Clearing Up Some Myths About Sex Work". www.opensocietyfoundations.org.

- Oxford English Dictionary, "sex worker"

- Weitzer 2009.

- Burnes, Theodore R. (2017). "Sex Work". In Nadal, Kevin L. (ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Psychology and Gender. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 1467–1470. doi:10.4135/9781483384269.n494. ISBN 9781483384283.

- "Carol Leigh coins the term "sex work"". www.nswp.org. 2014-11-04.

- Delacoste, Frédérique; Alexander, Priscilla (1987). Sex Work : Writings by Women in the Sex Industry (2nd ed.). Cleis Press Start. ISBN 9781573447010.

- "The Etymology of the terms 'Sex Work' and 'Sex Worker'", BAYSWAN.org. Accessed 2009-09-11.

- Nagle, Jill, ed. (1997). Whores and Other Feminists. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-91822-0.

- "Violence Against Sex Workers and HIV Prevention" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2005.

- "sex worker". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "Prostitution: Factsheet on Human Rights Violations". Prostitution Research & Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- Farley, Melissa (2003). "Prostitution and the Invisibility of Harm". Prostitiution Research & Education. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Farley, Melissa (2006). "Prostitution, trafficking, and cultural amnesia: What we must not know in order to keep the business of sexual exploitation running smoothly" (PDF). Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 18 (1): 109–144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

Some words hide the truth. Just as torture can be named enhanced interrogation, and logging of old-growth forests is named the Healthy Forest Initiative, words that lie about prostitution leave people confused about the nature of prostitution and trafficking. The words 'sex work' make the harms of prostitution invisible

- Baptie, Trisha (2009-04-29). "'Sex worker' ? Never met one !". Sisyphe.org. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- Sawicki, Danielle A.; Meffert, Brienna N.; Read, Kate; Heinz, Adrienne J. (2019-07-03). "Culturally competent health care for sex workers: an examination of myths that stigmatize sex work and hinder access to care". Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 34 (3): 355–371. doi:10.1080/14681994.2019.1574970. ISSN 1468-1994. PMC 6424363. PMID 30899197.

- Marcus, Anthony; Horning, Amber; Curtis, Ric; Sanson, Jo; Thompson, Efram (2014). "Conflict and Agency among Sex Workers and Pimps: A Closer Look at Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 653 (1): 225–246. doi:10.1177/0002716214521993. S2CID 145245482.

- Ryan, Chris; Kinder, Rachel (1996). "Sex, tourism and sex tourism: fulfilling similar needs?". Tourism Management. 17 (7): 507–518. doi:10.1016/s0261-5177(96)00068-4.

- Eichert, David (12 March 2022). "'It Ruined My Life: FOSTA, Male Escorts, and the Construction of Sexual Victimhood in American Politics" (PDF). Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law. 26 (3): 201–245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Harcourt, C; B Donovan (2005). "The many faces of sex work". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 81 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.012468. PMC 1744977. PMID 15923285.

- Givetash, Linda (14 April 2017). "Some Sex Workers Choose Industry Due to Benefits of Occupation: Study". The Globe and Mail. Toronto: Phillip Crawley.

- Breslin, Susannah (5 August 2011). "Why Do Women Become Sex Workers, and Why Do Men Go to Them?". The Guardian. UK.

- "End Trans Discrimination: Home". 1map.com.

- Dandona, Rakhi; Dandona, Lalit; Kumar, G Anil; Gutierrez, Juan Pablo; McPherson, Sam; Samuels, Fiona; Bertozzi, Stefano M.; ASCI FPP Study Team (April 2006). "Demography and sex work characteristics of female sex workers in India". BMC International Health and Human Rights. 6: 5. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-6-5. PMC 1468426. PMID 16615869.

- Katsulis, Yasmina (2009-09-15). Sex Work and the City. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292779808.

- Dank, Meredith; et al. (2016-06-28). "Estimating the Size and Structure of the Underground Commercial Sex Economy in Eight Major US Cities". Urban Institute. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Dank, Meredith. "Misconceptions about our report on the underground commercial sex economy". Urban Institute. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Shaver, Frances M. (March 2005). "Sex work research: methodological and ethical challenges". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 20 (3): 296–319. doi:10.1177/0886260504274340. PMID 15684139. S2CID 23470722.

- Weitzer, Ronald (2017-01-18). "Resistance to sex work stigma". Sexualities. 21 (5–6): 717–729. doi:10.1177/1363460716684509. ISSN 1363-4607. S2CID 151608068.

- Krüsi, Andrea; Kerr, Thomas; Taylor, Christina; Rhodes, Tim; Shannon, Kate (2016-04-26). "'They won't change it back in their heads that we're trash': the intersection of sex work-related stigma and evolving policing strategies". Sociology of Health & Illness. 38 (7): 1137–1150. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12436. ISSN 0141-9889. PMC 5012919. PMID 27113456.

- Oliveira, Alexandra (2018-03-01). "Same work, different oppression: Stigma and its consequences for male and transgender sex workers in Portugal". International Journal of Iberian Studies. 31 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1386/ijis.31.1.11_1. ISSN 1364-971X.

- Decker, Michele R; Pearson, Erin; Illangasekare, Samantha L; Clark, Erin; Sherman, Susan G (2013-09-23). "Violence against women in sex work and HIV risk implications differ qualitatively by perpetrator". BMC Public Health. 13 (1): 876. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-876. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 3852292. PMID 24060235.

- Maticka-Tyndale, Eleanor; Lewis, Jacqueline; Clark, Jocalyn P.; Zubick, Jennifer; Young, Shelley (2000-09-18). "Exotic Dancing and Health". Women & Health. 31 (1): 87–108. doi:10.1300/j013v31n01_06. ISSN 0363-0242. PMID 11005222. S2CID 35709367.

- Weitzer, Ronald (2010-02-21). "The Mythology of Prostitution: Advocacy Research and Public Policy". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 7 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1007/s13178-010-0002-5. ISSN 1868-9884. S2CID 144735092.

- "Ethiopia: Poverty forcing girls into risky sex work". PlusNews. 2006-10-18. Archived from the original on 2009-07-03.

- "IRIN Africa - KENYA: Desperate times: women sell sex to buy food - Kenya - HIV/AIDS". IRINnews. 2009-03-03.

- Cunningham, Stewart (March 2016). "Reinforcing or Challenging Stigma? The Risks and Benefits of 'Dignity Talk' in Sex Work Discourse". International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 29: 45–65. doi:10.1007/s11196-015-9434-9. S2CID 145353266. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Leigh, Carol (April 19, 2012). "Labor Laws, Not Criminal Laws, Are the Solution". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Ramos, Norma (April 19, 2012). "Such Oppression Can Never Be Safe". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Cho, Seo-Young; Dreher, Axel; Neumayer, Eric (2012). "Does Legalized Prostitution Increase Human Trafficking?". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1986065. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 39969233.

- Raymond, Leigh (October 15, 2008). "Ten Reasons for Not Legalizing Prostitution and a Legal Response to the Demand for Prostitution". Journal of Trauma Practice. 2 (3–4): 315–332. doi:10.1300/J189v02n03_17. S2CID 168039341.

- Deshpande, Neha A; Nour, Nawal M (2013). "Sex trafficking of women and girls". Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. ' (1): 22–27. PMC 3651545. PMID 23687554.

- Weitzer, Ronald John (2012). Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814794630.

- Weitzer 1991.

- Saunders, Penelope (March 2005). "Traffic Violations: Determining the Meaning of Violence in Sexual Trafficking versus Sex Work" (PDF). Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 20 (3): 343–360. doi:10.1177/0886260504272509. PMID 15684141. S2CID 42875911. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Tucker, Joseph; Astrid Tuminez (2011). "Reframing the Interpretation of Sex Worker Health: A Behavioral–Structural Approach". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (5): S1206–10. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir534. PMC 3205084. PMID 22043033.

- Kempadoo, Kamala (1998). Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance, and Redefinition. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9781317958673.

- Cohan, D (Oct 2006). "Sex Worker Health: San Francisco Style". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (5): 418–422. doi:10.1136/sti.2006.020628. PMC 2563853. PMID 16854996.

- Shannon, Kate; Joanne Csete (August 4, 2010). "Violence, Condom Negotiation, and HIV/STI Risk Among Sex Workers". JAMA. 304 (5): 573–574. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1090. PMID 20682941.

- Operario, Don (May 1, 2008). "Sex Work and HIV Status Among Transgender Women: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 48 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1097/qai.0b013e31816e3971. PMID 18344875. S2CID 20298656. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Potiat, Tonia (January 23, 2015). "HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers". The Lancet. 385 (9964): 274–286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. PMC 4320978. PMID 25059941.

- Tyndale, Maticka (2000). "Exotic dancing and health". Women & Health. 31 (1): 87–108. doi:10.1300/j013v31n01_06. PMID 11005222. S2CID 35709367.

- Barton, B (2007). "Managing the toll of stripping boundary-setting among exotic dancers". Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 36 (5): 571. doi:10.1177/0891241607301971. S2CID 140344003.

- Silverman, JG (18 March 2014). "Associations of Sex Trafficking History with Recent Sexual Risk among HIV-Infected FSWs in India". AIDS and Behavior. 18 (3): 55–61. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0564-3. PMC 4111225. PMID 23955657.

- Decker, Michele (23 September 2013). "Violence against women in sex work and HIV risk implications differ qualitatively by perpetrator". BMC Public Health. 13 (876): 876. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-876. PMC 3852292. PMID 24060235.

- Goldenberg, S.M. (14 June 2013). ""Right Here is the Gateway": Mobility, Sex Work Entry and HIV Risk Along the Mexico–US Border". International Migration. 52 (4): 26–40. doi:10.1111/imig.12104. PMC 4207057. PMID 25346548.

- "Not Everyone Is Happy with the NY Courts Treating Sex Workers as Trafficking Victims". VICE News. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- Cabezas, Amalia L. (2019-04-29). "Latin American and Caribbean Sex Workers: Gains and challenges in the movement". Anti-Trafficking Review (12): 37–56. doi:10.14197/atr.201219123. ISSN 2287-0113. S2CID 159172969.

- Gall, Gregor (1 January 2007). "Sex worker unionisation: an exploratory study of emerging collective organisation". Industrial Relations Journal. 38 (1): 70–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2338.2007.00436.x. S2CID 154670925.

- "IUSW: Who We Are". International Union of Sex Workers. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Sex Worker Rights Organizations and Projects Around the World". Prostitutes' Education Network.

- Brooks, S. (2001). Exotic dancing and unionizing: The challenges of feminist and antiracist organizing at the Lusty Lady Theater. Feminism and anti-racism: International struggles for justice, 59-70

- Chun, Sarah (1999). "An Uncommon Alliance: Finding Empowerment for Exotic Dancers through Labor Unions". Hastings Women's Law Journal. 10 (1): 231.

- O'Neil, John (August 2004). "Dhandha, dharma and disease: traditional sex work and HIV/AIDS in rural India". Social Science and Medicine. 59 (4): 851–860. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.032. PMID 15177840.

- Kaufman, Joan (2011). "HIV, Sex Work, and Civil Society in China". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (5): S1218–S1222. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir538. PMID 22043035.

- Raymond, Janice G. (January–February 1998). "Prostitution as violence against women: NGO stonewalling in Beijing and elsewhere". Women's Studies International Forum. 21 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/S0277-5395(96)00102-1.

Further reading

- "Decriminalize sex trade: Vancouver report". CBC News: British Columbia. 13 June 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Agustín, Laura Maria. Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London: Zed Books (2007) and The Naked Anthropologist.

- Chateauvert, Melinda. Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to SlutWalk. United States: Beacon Press (2014)

- Hughes, Christine (30 November 2007). "International Human Rights Protection in the Citizenship Gap: The Case of Migrant Sex Workers". Cultural Shift(s). Archived from the original on 2008-02-02. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- Minichiello, Victor and Scott, John, editors. Male Sex Work and Society. United Kingdom and United States: Harrington Park Press (2014)

- Prose & Lore: Issue 2: Memoir Stories About Sex Work (Volume 2) Red Umbrella Project

- Prose & Lore: Issue 3: Memoir Stories About Sex Work (Volume 3) Red Umbrella Project

- Stark, Christine. Not for Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography. Australia: Spinifex Press (2005)

- Weitzer, Ronald (1991). "Prostitutes' Rights in the United States". Sociological Quarterly. 32 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1991.tb00343.x.

- Weitzer, Ronald (2009). "Sociology of Sex Work". Annual Review of Sociology. 35: 213–234. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120025. S2CID 145372267.

- Weitzer, Ronald John (2000). Sex for Sale: Prostitution, Pornography, and the Sex Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92294-4.

External links

InternationalAfrica

AustraliaEurope |

North America

Anti-prostitution groups

|