Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a long-term inflammatory disorder which affects the skin and the muscles.[1] Its symptoms are generally a skin rash and worsening muscle weakness over time.[1] These may occur suddenly or develop over months.[1] Other symptoms may include weight loss, fever, lung inflammation, or light sensitivity.[1] Complications may include calcium deposits in muscles or skin.[1]

| Dermatomyositis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Discrete red areas overlying the knuckles in a person with juvenile dermatomyositis. These are known as Gottron's papules. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Rash, muscle weakness, weight loss, fever[1] |

| Complications | Calcinosis, lung inflammation, heart disease[1][2] |

| Usual onset | 40s to 50s[3] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, blood tests, electromyography, muscle biopsies[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Polymyositis, inclusion body myositis, scleroderma[3] |

| Treatment | Medication, physical therapy, exercise, heat therapy, orthotics, assistive devices, rest[1] |

| Medication | Corticosteroids, methotrexate, azathioprine[1] |

| Frequency | ~ 1 per 100,000 people per year[3] |

The cause is unknown.[1] Theories include that it is an autoimmune disease or a result of a viral infection.[1] Dermatomyositis may develop as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with several forms of malignancy.[4] It is a type of inflammatory myopathy.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on some combination of symptoms, blood tests, electromyography, and muscle biopsies.[3]

Eighty percent of adults with adult-onset dermatomyositis have a myositis-specific antibody (MSA).[5]

Sixty percent of children with juvenile dermatomyositis have a myositis-specific antibody (MSA).[6]

Although no cure for the condition is known, treatments generally improve symptoms.[1] Treatments may include medication, physical therapy, exercise, heat therapy, orthotics, and assistive devices, and rest.[1] Medications in the corticosteroids family are typically used with other agents such as methotrexate or azathioprine recommended if steroids are not working well.[1] Intravenous immunoglobulin may also improve outcomes.[1] Most people improve with treatment and in some, the condition resolves completely.[1]

About one per 100,000 people per year are newly affected.[3] The condition usually occurs in those in their 40s and 50s with women being affected more often than men.[3] People of any age, however, may be affected.[3] The condition was first described in the 1800s.[7]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms include several kinds of skin rash along with muscle weakness in both upper arms or thighs.[2]

Skin

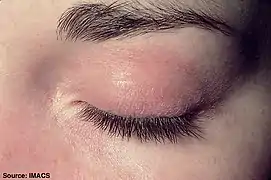

One form the rashes take is called "heliotrope" (a purplish color) or lilac, but may also be red. It can occur around the eyes along with swelling, but also occurs on the upper chest or back what is called the "shawl" (around the neck) or "V-sign" above the breasts and may also occur on the face, upper arms, thighs, or hands.[8] Another form the rash takes is called Gottron's sign which are red or violet, sometimes scaly, slightly raised papules that erupt on any of the finger joints (the metacarpophalangeal joints or the interphalangeal joints).[8][9] Gottron's papules may also be found over other bony prominences including the elbows, knees, or feet. All these rashes are made worse by exposure to sunlight, and are often very itchy, painful, and may bleed.[9]

If a person exhibits only skin findings characteristic of DM, without weakness or abnormal muscle enzymes, then he or she may be experiencing amyopathic dermatomyositis (ADM), formerly known as "dermatomyositis sine myositis".[10]

Muscles

People with DM experience progressively worsening muscle weakness in the proximal muscles (for example, the shoulders and thighs).[11] Tasks that use these muscles: standing from sitting, lifting, and climbing stairs, can become increasingly difficult for people with dermatomyositis.[11]

Other

Around 30% of people have swollen, painful joints, but this is generally mild.[12]

In some people, the condition affects the lungs, and they may have a cough or difficulty breathing. If the disease affects the heart, arrhythmias may occur. If it affects the blood vessels in the stomach or intestines, which is more common in juvenile DM, the people might vomit blood, have black tarry bowel movements, or may develop a hole somewhere in their GI tract.[12]

There are further complications possible with dermatomyositis. These complications include difficulty swallowing due to the muscles in the esophagus being affected which can result in malnutrition and can cause the breathing of food or liquids, into the lungs.

- Examples of dermatomyositis

Gottron's papules on finger joints

Gottron's papules on finger joints Gottron's papules on the elbows of a person with juvenile DM

Gottron's papules on the elbows of a person with juvenile DM Gottron's papules

Gottron's papules Gottron's bumps on a person with juvenile DM

Gottron's bumps on a person with juvenile DM Gottron's papules in a severe case of juvenile dermatomyositis

Gottron's papules in a severe case of juvenile dermatomyositis Heliotrope with swelling around the eyes

Heliotrope with swelling around the eyes Heliotrope

Heliotrope Facial rash

Facial rash Severe rash on the hands, extending up the forearm

Severe rash on the hands, extending up the forearm Forearm rash

Forearm rash

Causes

The cause is unknown, but it may result from an initial viral infection or cancer, either of which could raise an autoimmune response.[12]

Between 7 and 30% of dermatomyositis cases arise from cancer, probably as an autoimmune response.[13] The most commonly associated cancers are ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and lung cancer.[13] Between 18 and 25 per cent of people with amyopathic DM also have cancer.[9] Malignancy in association with dermatomyositis is more prevalent after age 60.

Some cases are inherited, and HLA subtypes HLA-DR3, HLA-DR52, and HLA-DR6 seem to create a disposition to autoimmune dermatomyositis.[12]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dermatomyositis is based on five criteria, which are also used to differentially diagnose with respect to polymyositis:[10]

- Muscle weakness in both thighs or both upper arms

- Using a blood test, finding higher levels of enzymes found in skeletal muscle, including creatine kinase, aldolase, and glutamate oxaloacetate, pyruvate transaminases and lactate dehydrogenase

- Using electromyography (testing of electric signalling in muscles), finding all three of: erratic, repetitive, high-frequency signals; short, low-energy signals between skeletal muscles and motor neurons that have multiple phases; and sharp activity when a needle is inserted into the muscle

- Examining a muscle biopsy under a microscope and finding mononuclear white blood cells between the muscle cells, and finding abnormal muscle cell degeneration and regeneration, dying muscle cells, and muscle cells being consumed by other cells (phagocytosis)

- Rashes typical of dermatomyositis, which include heliotrope rash, Gottron sign, and Gottron papules

The fifth criterion is what differentiates dermatomyositis from polymyositis; the diagnosis is considered definite for dermatomyositis if three of items 1 through 4 are present in addition to 5, probable with any two in addition to 5, and possible if just one is present in addition to 5.[10]

Dermatomyositis is associated with autoantibodies, especially antinuclear antibodies (ANA).[12] Around 80% of people with DM test positive for ANA and around 30% of people have myositis-specific autoantibodies which include antibodies to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (anti-synthetase antibodies), including antibodies against histidine—tRNA ligase (Anti-Jo1); antibodies to signal recognition particle (SRP); and anti-Mi-2 antibodies.[12]

Magnetic resonance imaging may be useful to guide muscle biopsy and to investigate involvement of internal organs;[14] X-ray may be used to investigate joint involvement and calcifications.[15]

A given case of dermatomyositis may be classified as amyopathic dermatomyositis if only skin is affected and no muscle weakness for longer than 6 months is seen according to one 2016 review,[10] or two years according to another.[9]

Classification

Dermatomyositis is a form of systemic connective tissue disorder, a class of diseases that often involves autoimmune dysfunction.[12][16]

It has also been classified as an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, along with polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myositis, cancer-associated myositis, and sporadic inclusion body myositis.[17]

A form of this disorder that occurs prior to adulthood is known as juvenile dermatomyositis.[18]

Treatment

No cure for dermatomyositis is known, but the symptoms can be treated. Options include medication, physical therapy, exercise, heat therapy (including microwave and ultrasound), orthotics and assistive devices, and rest. The standard treatment for dermatomyositis is a corticosteroid drug, given either in pill form or intravenously. Immunosuppressant drugs, such as azathioprine and methotrexate, may reduce inflammation in people who do not respond well to prednisone. Periodic treatment using intravenous immunoglobulin can also improve recovery. Other immunosuppressive agents used to treat the inflammation associated with dermatomyositis include cyclosporine A, cyclophosphamide, and tacrolimus.[19]

Physical therapy is usually recommended to prevent muscle atrophy and to regain muscle strength and range of motion. Many individuals with dermatomyositis may need a topical ointment, such as topical corticosteroids, for their skin disorder. They should wear high-protection sunscreen and protective clothing. Surgery may be required to remove calcium deposits that cause nerve pain and recurrent infections.[20]

Antimalarial medications, especially hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, are used to treat the rashes, as is done for similar conditions.[9]

Rituximab is used when people do not respond to other treatments.[21][22]

As of 2016, treatments for amyopathic dermatomyositis in adults did not have a strong evidence base; published treatments included antimalarial medications, steroids, taken or orally or applied to the skin, calcineurin inhibitors applied to the skin, dapsone, intravenous immunoglobulin, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil. None appears to be very effective; among them, intravenous immunoglobulin has had the best outcomes.[10]

Prognosis

Before the advent of modern treatments such as prednisone, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, chemotherapies, and other drugs, the prognosis was poor.[23]

The cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis may or may not improve with therapy in parallel with the improvement of the myositis. In some people, the weakness and rash resolve together. In others, the two are not linked, with one or the other being more challenging to control. Often, cutaneous disease persists after adequate control of the muscle disease.[24][25]

The risk of death from the condition is much higher if the heart or lungs are affected.[17][20]

Epidemiology

Incidence of DM peaks at ages 40–50, but the disease can affect people of all ages.[26][3] It tends to affect more women than men.[3] The prevalence of DM ranges from one to 22 per 100,000 people.[27][28][29]

History

The diagnostic criteria were proposed in 1975 and became widely adopted.[9][30] Amyopathic DM, also called DM sine myositis, was named in 2002.[9]

People who died with dermatomyositis

- Opera singer Maria Callas (1923–1977) allegedly had dermatomyositis from 1975 until her death.[31]

- Actor Laurence Olivier (1907–1989) had dermatomyositis from 1974 until his death.[32]

- American football running back Ricky Bell (1955–1984), the runner-up for the Heisman Trophy in 1976, and the number-one pick in the NFL draft in 1977, died at the age of 29 from heart failure caused by this disease.[33]

- Rob Buckman (1948–2011) a doctor, comedian, author, and the president of the Humanist Association of Canada.[34][35]

Research

As of 2016, research was ongoing into causes for DM, as well as biomarkers;[36] clinical trials were ongoing for use of the following drugs in DM: ajulemic acid (Phase II), adrenocorticotropic hormone gel (Phase IV, open label), IMO-8400, an antagonist of Toll-like receptor 7,8 and 9 (Ph II), abatacept (Phase IV, open label), and sodium thiosulfate (Phase II).[9]

References

- "Dermatomyositis". GARD. 2017. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Callen, Jeffrey P.; Wortmann, Robert L. (September 2006). "Dermatomyositis". Clinics in Dermatology. 24 (5): 363–373. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.001. PMID 16966018.

- "Dermatomyositis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Tudorancea, Andreea Daniela; Ciurea, Paulina Lucia; Vreju, Ananu Florentin; Turcu-Stiolica, Adina; Gofita, Cristina Elena; Criveanu, Cristina; Musetescu, Anca Emanuela; Dinescu, Stefan Cristian (July 2021). "A Study on Dermatomyositis and the Relation to Malignancy". Current Health Sciences Journal. 47 (3): 377–382. doi:10.12865/CHSJ.47.03.07. PMC 8679146. PMID 35003769.

- Tansley, Sarah L; McHugh, Neil J; Wedderburn, Lucy R (2013). "Adult and juvenile dermatomyositis: are the distinct clinical features explained by our current understanding of serological subgroups and pathogenic mechanisms?". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 15 (2): 211. doi:10.1186/ar4198. PMC 3672700. PMID 23566358.

Myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs) can now be identified in 80% of adults.

- Papadopoulou, Charalampia; Chew, Christine; Wilkinson, Meredyth G. Ll; McCann, Liza; Wedderburn, Lucy R. (June 2023). "Juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myositis: an update on pathophysiology and clinical care". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 19 (6): 343–362. doi:10.1038/s41584-023-00967-9. PMC 10184643. PMID 37188756.

Approximately 60% of patients with JDM are positive for a myositis-specific antibody (MSA).

- "History of Dermatomyositis". Dermatomyositis. 2009. pp. 5–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-79313-7_2. ISBN 978-3-540-79312-0.

- Callen, Jeffrey P. (June 2010). "Cutaneous Manifestations of Dermatomyositis and Their Management". Current Rheumatology Reports. 12 (3): 192–197. doi:10.1007/s11926-010-0100-7. PMID 20425525. S2CID 29083422.

- Kuhn, A; Landmann, A; Bonsmann, G (October 2016). "The skin in autoimmune diseases-Unmet needs". Autoimmunity Reviews. 15 (10): 948–54. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.013. PMID 27481041.

- Callander, J; Robson, Y; Ingram, J; Piguet, V (11 May 2016). "Treatment of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis in adults: a systematic review". The British Journal of Dermatology. 179 (6): 1248–1255. doi:10.1111/bjd.14726. PMID 27167896. S2CID 45638288.

- Dalakas, Marinos C. (30 April 2015). "Inflammatory Muscle Diseases". New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (18): 1734–1747. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1402225. PMID 25923553. S2CID 37761391.

- Hajj-ali, Rula A. (June 2013). "Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis – Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015.

- Di Rollo, D.; Abeni, D.; Tracanna, M.; Capo, A.; Amerio, P. (October 2014). "Cancer risk in dermatomyositis: a systematic review of the literature". Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 149 (5): 525–537. PMID 24975953.

- Simon, JP; Marie, I; Jouen, F; Boyer, O; Martinet, J (14 June 2016). "Autoimmune Myopathies: Where Do We Stand?". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 234. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00234. PMC 4905946. PMID 27379096.

- Ramos-E-Silva, M; Lima Pinto, AP; Pirmez, R; Cuzzi, T; Carneiro, S (1 October 2016). "Dermatomyositis-Part 2: Diagnosis, Association With Malignancy, and Treatment". Skinmed. 14 (5): 354–358. PMID 27871347.

- "ICD-10 Systemic connective tissue disorders (M30-M36)". WHO. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Danieli, MG; Gelardi, C; Guerra, F; Cardinaletti, P; Pedini, V; Gabrielli, A (May 2016). "Cardiac involvement in polymyositis and dermatomyositis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 15 (5): 462–5. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.01.015. PMID 26826433.

- Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, Pachman LM (June 2008). "Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood". Lancet. 371 (9631): 2201–2212. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60955-1. PMID 18586175. S2CID 205951454.

- "Dermatomyositis (DM)". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- "Dermatomyositis Information". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- Malik, A; Hayat, G; Kalia, JS; Guzman, MA (20 May 2016). "Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies: Clinical Approach and Management". Frontiers in Neurology. 7: 64. doi:10.3389/fneur.2016.00064. PMC 4873503. PMID 27242652.

- Wright, NA; Vleugels, RA; Callen, JP (January 2016). "Cutaneous dermatomyositis in the era of biologicals". Seminars in Immunopathology. 38 (1): 113–21. doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0543-z. PMID 26563285. S2CID 7104535.

- Page 285 in: Thomson and Cotton Lecture Notes in Pathology, Blackwell Scientific. Third Edition

- "Dermatomyositis". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- "Dermatomyositis". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- Tymms, K. E.; Webb, J. (December 1985). "Dermatopolymyositis and other connective tissue diseases: a review of 105 cases". The Journal of Rheumatology. 12 (6): 1140–1148. PMID 4093921.

- Cooper, Glinda S; Stroehla, Berrit C (May 2003). "The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases". Autoimmunity Reviews. 2 (3): 119–125. doi:10.1016/s1568-9972(03)00006-5. PMID 12848952.

- Bernatsky, S; Joseph, L; Pineau, C A; Belisle, P; Boivin, J F; Banerjee, D; Clarke, A E (July 2009). "Estimating the prevalence of polymyositis and dermatomyositis from administrative data: age, sex and regional differences". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 68 (7): 1192–1196. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.093161. PMID 18713785. S2CID 21500536.

- Bendewald, Margo J.; Wetter, David A.; Li, Xujian; Davis, Mark D. P. (2010). "Incidence of Dermatomyositis and Clinically Amyopathic Dermatomyositis: A Population-Based Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota". Archives of Dermatology. 146 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.328. PMC 2886726. PMID 20083689.

- Bohan, Anthony; Peter, James B. (13 February 1975). "Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis: (First of Two Parts)". New England Journal of Medicine. 292 (7): 344–347. doi:10.1056/nejm197502132920706. PMID 1090839. and Bohan, Anthony; Peter, James B. (20 February 1975). "Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis: (Second of Two Parts)". New England Journal of Medicine. 292 (8): 403–407. doi:10.1056/nejm197502202920807. PMID 1089199.

- "Greek Reporter: 'Maria Callas did not kill herself from grief for Onassis, a rare disease cost her career and life'". GR Reporter. 28 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Laurence Olivier Dies: 'The Rest Is Silence'". People Magazine. 24 July 1989. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- "Forgotten: Ricky Bell". Pro Football Weekly. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Jones, Terry (12 October 2011). "Rob Buckman obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- "Dr. Robert Buckman, renowned oncologist, comedian and Star columnist, dead at 63". Toronto Star. 10 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Ramos-E-Silva, M; Pinto, AP; Pirmez, R; Cuzzi, T; Carneiro, SC (1 August 2016). "Dermatomyositis—Part 1: Definition, Epidemiology, Etiology and Pathogenesis, and Clinics". Skinmed. 14 (4): 273–279. PMID 27784516.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from NINDS Dermatomyositis Information Page. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from NINDS Dermatomyositis Information Page. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 12 December 2016.