Shawmut Peninsula

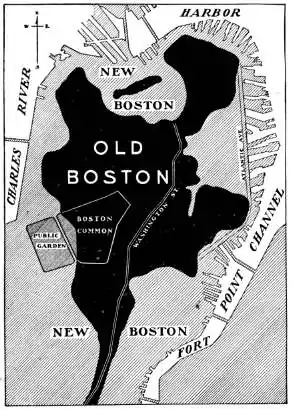

Shawmut Peninsula is the promontory of land on which Boston, Massachusetts was built. The peninsula, originally a mere 789 acres (3.19 km2) in area,[1] more than doubled in size due to land reclamation efforts that were a feature of the history of Boston throughout the 19th century.

Geology and original topography

Like much of the Massachusetts landscape, the peninsula was shaped by glacial erosion and moraine deposits left by retreating glaciers at the end of the last ice age.[1] When Europeans arrived, Shawmut was thickly forested.[1] The pre-settlement topography of the peninsula was marked by three hills: Copps Hill, in what is now the North End; Fort Hill, in today's Financial District; and the Trimountain, today's Beacon Hill district. Of the three hills, the Trimountain was by far the largest, a steep-sided mass with three summits. Its name was eventually shortened to Tremont. To the south was a narrow isthmus named Boston Neck that connected the peninsula to the mainland site of Roxbury, now a neighborhood of Boston.

English settlement

The name is derived from Mashauwomuk, an Algonquian word of uncertain meaning. The first recorded use of "Shawmutt" to describe the peninsula occurs in 1630, by the lone settler William Blackstone,[2] in an invitation to John Winthrop to move the site of Winthrop's colonial settlement to the peninsula from what is now Charlestown. The Charlestown peninsula lacked a source of fresh water, while the Shawmut peninsula had an "excellent spring" on the north side of what is now Beacon Hill.[3]

Land reclamation

Reclamation projects began in 1820 and continued intermittently until 1900 and created the Boston neighborhoods of the South End, Back Bay, and Fenway-Kenmore. The Back Bay Fens, a freshwater urban wild in the latter area, is a remnant of the salt marshes that once surrounded Shawmut Peninsula.

Although this project eliminated the wetland ecosystem that existed there at the time and would be impossible under modern environmental regulations, it was considered a great boon to the community for two reasons. Firstly, it eliminated the foul-smelling tidal flats that had become polluted with sewage. Secondly, it created what is now some of the most valuable real estate in New England.

Notes

- Miller, Bradford A., "Digging up Boston: The Big Dig Builds on Centuries of Geological Engineering", GeoTimes, October 2002.

- Horsford, Eben Norton, The Indian Names of Boston, and their Meaning, John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, MA, University Press, 1886.

- Shurtleff, Nathaniel B., A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston, printed by request of Boston City Council, Boston, 1871.