Shawnee

The Shawnee (/ʃɔːˈni/ shaw-NEE) are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

The Shawnee Prophet, Tenskwatawa (1775–1836), ca. 1820, portrait by Charles Bird King | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 7,584 enrolled[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Oklahoma), formerly Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and surrounding states[2][1] | |

| Languages | |

| Shawnee, English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religions, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Miami, Menominee, Cheyenne[3] |

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio.[2] In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohio, Illinois, Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.[4] In the early 18th century, they mostly concentrated in eastern Pennsylvania but dispersed again later that century across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, with a small group joining Muscogee people in Alabama.[2] By the 19th century, the U.S. federal government forcibly removed them under the 1830 Indian Removal Act to areas west of the Mississippi River: which became the states of Missouri, Kansas, Texas. Finally, they were removed to Indian Territory, which became the state of Oklahoma in the early 20th century.[2]

Today, Shawnee people are enrolled in three federally recognized tribes, all headquartered in Oklahoma:

Etymology

Shawnee has also been written as Shaawana.[5] Individuals and singular Shawnee tribes may be referred to as šaawanwa, and the collective Shawnee people as šaawanwaki or šaawanooki.[5]

Algonquian languages have words similar to the archaic shawano (now: shaawanwa) meaning "south". However, the stem šawa- does not mean "south" in Shawnee, but "moderate, warm (of weather)": See Charles F. Voegelin, "šawa (plus -ni, -te) Moderate, Warm. Cp. šawani 'it is moderating...".[6] In one Shawnee tale, "Sawage" (šaawaki) is the deity of the south wind.[7] Jeremiah Curtin translates Sawage as 'it thaws', referring to the warm weather of the south. In an account and a song collected by C. F. Voegelin, šaawaki is attested as the spirit of the South, or the South Wind.[8][9]

Language

The Shawnee language is known as saawanwaatoweewe.[10] In 2002, the Shawnee language, part of the Algonquian family, was in decline but still spoken by 200 people. These included more than 100 Absentee Shawnee and 12 Shawnee Tribe speakers. By 2017, Shawnee language advocates, including tribal member George Blanchard, estimated that there were fewer than 100 speakers. Most fluent Shawnee speakers are over the age of 50.[11]

The language is written in the Latin script, but attempts at creating a unified spelling system have been unsuccessful.[12] The Shawnee language has a dictionary, and portions of the Bible have been translated into Shawnee.[13]

History

Precontact history

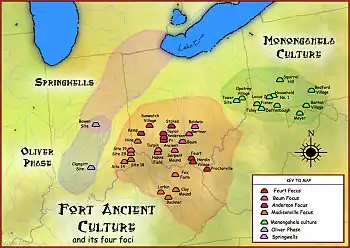

Some scholars believe that the Shawnee descend from the precontact Fort Ancient culture of the Ohio region, although this is not universally accepted. The Shawnee may have entered the area at a later time and occupied the Fort Ancient sites.[14][15][16]

Fort Ancient culture flourished from c. 1000 to c. 1650 CE among a people who predominantly inhabited lands on both sides of the Ohio River in areas of present-day southern Ohio, northern Kentucky and western West Virginia.[17] Like the Mississippian culture peoples of this period, they built earthwork mounds as part of their expression of their religious and political structure. Fort Ancient culture was once thought to have been a regional extension of the Mississippian culture. Scholars now believe that Fort Ancient culture (1000–1650 CE) was descended from Hopewell culture (100 BCE–500 CE).[18][5][17] The people in those earlier centuries also built mounds as part of their social, political and religious system. Among their monuments were earthwork effigy mounds, such as Serpent Mound in present-day Ohio.

Uncertainty surrounds the fate of the Fort Ancient people. Most likely their society, like the Mississippian culture to the south, was severely disrupted by waves of epidemics from new infectious diseases carried by the first Spanish explorers in the 16th century.[19] After 1525 at Madisonville, the type site, the village's house sizes became smaller and fewer. Evidence shows that the people changed from their previously "horticulture-centered, sedentary way of life".[19][20]

There is a gap in the archaeological record between the most recent Fort Ancient sites and the oldest sites of the historic Shawnee. The latter were recorded by European (French and English) archaeologists as occupying this area at the time of encounter. Scholars generally accept that similarities in material culture, art, mythology, and Shawnee oral history linking them to the Fort Ancient peoples, can be used to support the connection from Fort Ancient society and development as the historical Shawnee society. But there is also evidence and oral history linking Siouan-speaking nations to the Ohio Valley.[21]

The Shawnee considered the Lenape (or Delaware) of the East Coast mid-Atlantic region, who were also Algonquian speaking, to be their "grandfathers." The Algonquian nations of present-day Canada, who extended to the interior along the St. Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes from the Atlantic coast, regarded the Shawnee as their southernmost branch. Along the East Coast, the Algonquian-speaking tribes were historically located mostly in coastal areas, from Quebec to the Carolinas.

17th century

Europeans reported encountering the Shawnee over a wide geographic area. One of the earliest mentions of the Shawnee may be a 1614 Dutch map showing some Sawwanew located just east of the Delaware River. Later 17th-century Dutch sources also place them in this general location. Accounts by French explorers in the same century usually located the Shawnee along the Ohio River, where the French encountered them on forays from eastern Canada and the Illinois Country.[22]

Based on historical accounts and later archaeology, John E. Kleber describes Shawnee towns by the following:

A Shawnee town might have from forty to one hundred bark-covered houses similar in construction to Iroquois longhouses. Each village usually had a meeting house or council house, perhaps sixty to ninety feet long, where public deliberations took place.[23]

According to one English colonial legend, some Shawnee were descended from a party sent by Chief Opechancanough, ruler of the Powhatan Confederacy of 1618–1644, to settle in the Shenandoah Valley. The party was led by his son, Sheewa-a-nee.[24] Edward Bland, an explorer who accompanied Abraham Wood's expedition in 1650, wrote that in Opechancanough's day, there had been a falling-out between the Chawan chief and the weroance of the Powhatan (also a relative of Opechancanough's family). He said the latter had murdered the former.[25] The Shawnee were "driven from Kentucky in the 1670s by the Iroquois of Pennsylvania and New York, who claimed the Ohio valley as hunting ground to supply its fur trade.[23] In 1671, the colonists Batts and Fallam reported that the Shawnee were contesting control of the Shenandoah Valley with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois) in that year and were losing.

Sometime before 1670, a group of Shawnee migrated to the Savannah River area. The English based in Charles Town, South Carolina, were contacted by these Shawnee in 1674. They forged a long-lasting alliance. The Savannah River Shawnee were known to the Carolina English as "Savannah Indians". Around the same time, other Shawnee groups migrated to Florida, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and other regions south and east of the Ohio country. Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, founder of New Orleans and the French colony of La Louisiane, writing in his journal in 1699, describes the Shawnee (or as he spells them, Chaouenons) as "the single nation to fear, being spread out over Carolina and Virginia in the direction of the Mississippi."[26]

Historian Alan Gallay speculates that the Shawnee migrations of the middle to late 17th century were probably driven by the Beaver Wars, which began in the 1640s. Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy invaded from the east to secure the Ohio Valley for hunting grounds. The Shawnee became known for their widespread settlements, extending from Pennsylvania to Illinois and to Georgia. Among their known villages were Eskippakithiki in Kentucky, Sonnionto (also known as Lower Shawneetown) in Ohio, Chalakagay near what is now Sylacauga, Alabama,[27] Chalahgawtha at the site of present-day Chillicothe, Ohio, Old Shawneetown, Illinois, and Suwanee, Georgia. Their language became a lingua franca for trade among numerous tribes. They became leaders among the tribes, initiating and sustaining pan-Indian resistance to European and Euro-American expansion.[28]

18th century

Some Shawnee occupied areas in central Pennsylvania. Long without a chief, in 1714 they asked Carondawana, an Oneida war chief, to represent them to the Pennsylvania provincial council. About 1727 Carondawana and his wife, a prominent interpreter known as Madame Montour, settled at Otstonwakin, on the west bank at the confluence of Loyalsock Creek and the West Branch Susquehanna River.[29]

By 1730, European-American settlers began to arrive in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, where the Shawnee predominated in the northern part of the valley. They were claimed as tributaries by the Haudenosaunee or Six Nations of the Iroquois to the north. The Iroquois had helped some of the Tuscarora people from North Carolina, who were also Iroquoian speaking and distant relations, to resettle in the vicinity of what is now Martinsburg, West Virginia. Most of the Tuscarora migrated to New York and settled near the Oneida people, becoming the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy; they declared their migration finished in 1722. Also at this time, Seneca (an Iroquois nation) and Lenape war parties from the north often fought pitched battles with pursuing bands of Catawba from Virginia, who would overtake them in the Shawnee-inhabited regions of the Valley.

By the late 1730s pressure from colonial expansion produced repeated conflicts. Shawnee communities were also impacted by the fur trade. While they gained arms and European goods, they also traded for rum or brandy, leading to serious social problems related to alcohol abuse by their members. Several Shawnee communities in the Province of Pennsylvania, led by Peter Chartier, a métis trader, opposed the sale of alcohol in their communities. This resulted in a conflict with colonial Governor Patrick Gordon, who was under pressure from traders to allow rum and brandy in trade. Unable to protect themselves, in 1745 some 400 Shawnee migrated from Pennsylvania to Ohio, Kentucky, Alabama and Illinois, hoping to escape the traders' influence.[30]

Prior to 1754, the Shawnee had a headquarters at Shawnee Springs at modern-day Cross Junction, Virginia. The father of the later chief Cornstalk held his council there. Several other Shawnee villages were located in the northern Shenandoah Valley: at Moorefield, West Virginia, on the North River; and on the Potomac at Cumberland, Maryland. In 1753, the Shawnee on the Scioto River in the Ohio Country sent messengers to those still in the Shenandoah Valley, suggesting that they cross the Alleghenies to join the people further west, which they did the following year.[31][32] The community known as Shannoah (Lower Shawneetown) on the Ohio River increased to around 1,200 people by 1750.[33]

"[I] saw four Indian Chiefs of the Shawnee Nation, who have been at War with the Virginians this summer (i.e. 1774), but have made peace with them, and they are sending these people to Williamsburg as hostages. They are tall, manly, well-shaped men, of a Copper colour with black hair, quick piercing eyes, and good features. They have rings of silver in their nose and bobs to them which hang over their upper lip. Their ears are cut from the tips two thirds of the way round and the piece extended with brass wire till it touches their shoulders, in this part they hang a thin silver plate, wrought in flourishes about three inches diameter, with plates of silver round their arms and in the hair, which is all cut off except a long lock on the top of the head. They are in white men's dress, except breeches which they refuse to wear, instead of which they have a girdle round them with a piece of cloth drawn through their legs and turned over the girdle, and appears like a short apron before and behind. All the hair is pulled from their eyebrows and eyelashes and their faces painted in different parts with Vermilion. They walk remarkably straight and cut a grotesque appearance in this mixed dress."

— from the Journal of Nicholas Cresswell[34]

Ever since the Beaver Wars, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had claimed the Ohio Country as their hunting ground by right of conquest, and treated the Shawnee and Lenape who resettled there as dependent tribes. Some independent Iroquois bands from various tribes also migrated westward, where they became known in Ohio as the Mingo. These three tribes—the Shawnee, the Delaware (Lenape), and the Mingo—became closely associated with one another, despite the differences in their languages. The first two spoke Algonquian languages and the third an Iroquoian language.

After taking part in the first phase of the French and Indian War (also known as "Braddock's War") as allies of the French,[35] the Shawnee switched sides in 1758. They made formal peace with the British colonies at the Treaty of Easton, which recognized the Allegheny Ridge (the Eastern Divide) as their mutual border. This peace lasted only until Pontiac's War erupted in 1763, following Britain's defeat of France and takeover of its territory east of the Mississippi River in North America. Later that year, the Crown issued the Proclamation of 1763, legally confirming the 1758 border as the limits of British colonization. They reserved the land beyond for Native Americans. But the Crown had difficulty enforcing the boundary, as Anglo-European colonists continued to move westward.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768 extended the colonial boundary to the west, giving British colonists a claim to lands in what are now the states of West Virginia and Kentucky. The Shawnee did not agree to this treaty: it was negotiated between British officials and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who claimed sovereignty over the land. While they predominated, the Shawnee and other Native American tribes also hunted there. After the Stanwix treaty, Anglo-Americans began pouring into the Ohio River Valley for settlement, frequently traveling by boats and barges along the Ohio River. Violent incidents between settlers and Indians escalated into Lord Dunmore's War in 1774. British diplomats managed to isolate the Shawnee during the conflict: the Iroquois and the Lenape stayed neutral. The Shawnee faced the British colony of Virginia with only a few Mingo allies. Lord Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia, launched a two-pronged invasion into the Ohio Country. The Shawnee chief Cornstalk attacked one wing but fought to a draw in the only major battle of the war, the Battle of Point Pleasant. In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte ending the war (1774), Cornstalk and the Shawnee were compelled by the British to recognize the Ohio River as their southern border, which had been established by the Fort Stanwix treaty. By this treaty, the Shawnee ceded all claims to the "hunting grounds" of West Virginia and Kentucky south of the Ohio River. But many other Shawnee leaders refused to recognize this boundary. The Shawnee and most other tribes were highly decentralized, and bands and towns typically made their own decisions about alliances.

American Revolution

When the United States declared independence from the British crown in 1776, the Shawnee were divided. They did not support the American rebel cause. Cornstalk led the minority who wished to remain neutral. The Shawnee north of the Ohio River were unhappy about the American settlement of Kentucky. Colin Calloway reports that most Shawnees allied with the British against the Americans, hoping to be able to expel the settlers from west of the mountains.[36]

War leaders such as Blackfish and Blue Jacket joined Dragging Canoe and a band of Cherokee along the lower Tennessee River and Chickamauga Creek against the colonists in that area. Some colonists called this group of Cherokee the Chickamauga, because they lived along that river at the time of what became known as the Cherokee–American wars, during and after the American Revolution. But they were never a separate tribe, as some accounts suggested.[36]

After the Revolution and during the Northwest Indian War, the Shawnee collaborated with the Miami to form a great fighting force in the Ohio Valley. They led a confederation of warriors of Native American tribes in an effort to expel U.S. settlers from that territory. After being defeated by U.S. forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, most of the Shawnee bands signed the Treaty of Greenville the next year. They were forced to cede large parts of their homeland to the new United States. Other Shawnee groups rejected this treaty, migrating independently to Missouri west of the Mississippi River, where they settled along Apple Creek. The French called their settlement Le Grand Village Sauvage.

Tecumseh's War and the War of 1812

In the early 19th century, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh gained renown for organizing his namesake confederacy to oppose American expansion in Native American lands. The resulting conflict came to be known as Tecumseh's War. The two principal adversaries in the conflict, chief Tecumseh and General William Henry Harrison, had both been junior participants in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Tecumseh was not among the Native American signers of the Treaty of Greenville. However, many Indian leaders in the region accepted the Greenville terms, and for the next ten years pan-tribal resistance to American hegemony faded.

In September 1809 Harrison, as governor of the Indiana Territory, invited the Potawatomi, Lenape, Eel River people, and the Miami to a meeting at Fort Wayne. In the negotiations, Harrison promised large subsidies to the tribes if they would cede the lands he was asking for.[37] After two weeks of negotiating, the Potawatomi leaders convinced the Miami to accept the treaty as reciprocity, because the Potawatomi had earlier accepted treaties less advantageous to them at the request of the Miami. Finally, the tribes signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne on September 30, 1809, thereby selling the United States over 3,000,000 acres (approximately 12,000 km2), chiefly along the Wabash River north of Vincennes, Indiana.[37]

Tecumseh was outraged by the Treaty of Fort Wayne, believing that American Indian land was owned in common by all tribes, an idea advocated in previous years by the Shawnee leader Blue Jacket and the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant.[38] In response, Tecumseh began to expand on the teachings of his brother Tenskwatawa, a spiritual leader known as The Prophet who called for the tribes to return to their ancestral ways. He began to associate these teachings with the idea of a pan-tribal alliance. Tecumseh traveled widely, urging warriors to abandon accommodationist chiefs and to join the resistance at Prophetstown.[38] In August 1810, Tecumseh led 400 armed warriors to confront Governor Harrison in Vincennes. Tecumseh demanded that Harrison nullify the Fort Wayne treaty, threatening to kill the chiefs who had signed it.[39] Harrison refused, saying that the Miami were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so chose.[40] Tecumseh left peacefully but warned Harrison that he would seek an alliance with the British unless the treaty was nullified.[41]

Great Comet of 1811 and Tekoomsē

In March the Great Comet of 1811 appeared. During the next year, tensions between American colonists and Native Americans rose quickly. Four settlers were murdered along the Missouri River and, in another incident, natives seized a boatload of supplies from a group of traders. Harrison summoned Tecumseh to Vincennes to explain the actions of his allies.[41] In August 1811, the two leaders met, with Tecumseh assuring Harrison that the Shawnee intended to remain at peace with the United States.

Afterward, Tecumseh traveled to the Southeast on a mission to recruit allies against the United States from among the "Five Civilized Tribes." His name Tekoomsē meant "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across The Sky."[42]

Tecumseh told the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, and many others that the comet of March 1811 had signaled his coming. He also said that the people would see a sign proving that the Great Spirit had sent him.

While Tecumseh was traveling, both sides readied for the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison assembled a small force of army regulars and militia to combat the Native forces.[43] On November 6, 1811, Harrison led this army of about 1,000 men to Prophetstown, Indiana, hoping to disperse Tecumseh's confederacy.[44] Early next morning, forces under The Prophet prematurely attacked Harrison's army at the Tippecanoe River near the Wabash. Though outnumbered, Harrison repulsed the attack, forcing the Natives to retreat and abandon Prophetstown. Harrison's men burned the village and returned home.[45]

New Madrid earthquake

On December 11, 1811, the New Madrid earthquake shook the Muscogee lands and the Midwest. While the interpretation of this event varied from tribe to tribe, they agreed that the powerful earthquake had to have spiritual significance. The earthquake and its aftershocks helped the Tecumseh resistance movement as the Muscogee and other Native American tribes believed it was a sign that the Shawnee must be supported and that Tecumseh had prophesied such an event and sign.

The Indians were filled with great terror ... the trees and wigwams shook exceedingly; the ice which skirted the margin of the Arkansas river was broken into pieces; and most of the Indians thought that the Great Spirit, angry with the human race, was about to destroy the world.

— Roger L. Nichols, The American Indian

Tribal involvement in the War of 1812

The Muscogee who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the Red Sticks. They were the more conservative and traditional part of the people, as their communities in the Upper Towns were more isolated from European-American settlements. They did not want to assimilate. The Red Sticks rose in resisting the Lower Creek, and the bands became involved in civil war, known as the Creek War. This became part of the War of 1812 when open conflict broke out between American soldiers and the Red Sticks of the Creek.[46]

Portraits of the Choctaw chief Pushmataha (left) and Tecumseh. These white Americans ... give us fair exchange, their cloth, their guns, their tools, implements, and other things which the Choctaws need but do not make ... They doctored our sick; they clothed our suffering; they fed our hungry ... So in marked contrast with the experience of the Shawnees, it will be seen that the whites and Indians in this section are living on friendly and mutually beneficial terms.—Pushmataha, 1811 – Sharing Choctaw History.[47] --------------------- Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mohican, the Pocanet and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow before the summer sun ... Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws ... Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?—Tecumseh, 1811[48][49] |

After William Hull's surrender of Detroit to the British during the War of 1812, General William Henry Harrison was given command of the U.S. Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was defended by British Colonel Henry Procter, together with Tecumseh and his forces. A detachment of Harrison's army was defeated at Frenchtown along the River Raisin on January 22, 1813. Some prisoners were taken to Detroit, but Procter left those too injured to travel with an inadequate guard. His Native American allies attacked and killed perhaps as many as 60 wounded Americans, many of whom were Kentucky militiamen.[50] The Americans called the incident the "River Raisin Massacre." The defeat ended Harrison's campaign against Detroit, and the phrase "Remember the River Raisin!" became a rallying cry for the Americans.

In May 1813, Procter and Tecumseh besieged Fort Meigs in northern Ohio. American reinforcements arriving during the siege were defeated by the Natives, but the garrison in the fort held out. The Indians eventually began to disperse, forcing Procter and Tecumseh to return to Canada. Their second offensive in July against Fort Meigs also failed. To improve Indian morale, Procter and Tecumseh attempted to storm Fort Stephenson, a small American post on the Sandusky River. After they were repulsed with serious losses, the British and Tecumseh ended their Ohio campaign.

On Lake Erie, the American commander Captain Oliver Hazard Perry fought the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. His decisive victory against the British ensured American control of the lake, improved American morale after a series of defeats, and compelled the British to fall back from Detroit. General Harrison launched another invasion of Upper Canada (Ontario), which culminated in the U.S. victory at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813. Tecumseh was killed there, and his death effectively ended the North American Indigenous alliance with the British in the Detroit region. American control of Lake Erie meant the British could no longer provide essential military supplies to their aboriginal allies, who dropped out of the war. The Americans controlled the area during the remainder of the conflict.

Aftermath

The Shawnee in Missouri migrated from the United States south into Mexico, in the eastern part of Spanish Texas. They became known as the "Absentee Shawnee." They were joined in the migration by some Delaware (Lenape). Although they were closely allied with the Cherokee led by The Bowl, their chief John Linney remained neutral during the 1839 Cherokee War.[51]

Texas achieved independence from Mexico under American leaders. It decided to force removal of the Shawnee from the new republic. But in appreciation of their earlier neutrality, Texan President Mirabeau Lamar fully compensated the Shawnee for their improvements and crops. They were forced out to Arkansas Territory.[51] The Shawnee settled close to present-day Shawnee, Oklahoma. They were joined by Shawnee pushed out of Kansas (see below), who shared their traditionalist views and beliefs.

In 1817, the Ohio Shawnee had signed the Treaty of Fort Meigs, ceding their remaining lands in exchange for three reservations in Wapaughkonetta, Hog Creek (near Lima), and Lewistown, Ohio. They shared these lands with some Seneca people who had migrated west from New York.

In a series of treaties, including the Treaty of Lewistown of 1825, Shawnee and Seneca people agreed to exchange land in western Ohio with the United States for land west of the Mississippi River in what became Indian Territory.[52] In July 1831, the Lewistown group of Seneca–Shawnee departed for the Indian Territory (in present-day Kansas and Oklahoma).

The main body of Shawnee in Ohio followed Black Hoof, who fought every effort to force his people to give up their homeland. After the death of Black Hoof, the remaining 400 Ohio Shawnee in Wapaughkonetta and Hog Creek surrendered their land and moved to the Shawnee Reserve in Kansas. This movement was largely under terms negotiated by Joseph Parks (1793-1859). He had been raised in the household of Lewis Cass and had been a leading interpreter for the Shawnee.[53]

Missouri joined the Union in 1821. After the Treaty of St. Louis in 1825, the 1,400 Missouri Shawnee were forcibly relocated from Cape Girardeau, along the west bank of the Mississippi River, to southeastern Kansas, close to the Neosho River.

During 1833, only Black Bob's band of Shawnee resisted removal. They settled in northeastern Kansas near Olathe and along the Kansas (Kaw) River in Monticello near Gum Springs. The Shawnee Methodist Mission was built nearby to minister to the tribe. About 200 of the Ohio Shawnee followed the prophet Tenskwatawa and had joined their Kansas brothers and sisters here in 1826.

In the mid-1830s two companies of Shawnee soldiers were recruited into United States service to fight in the Seminole War in Florida. One of these was led by Joseph Parks, who had earlier helped negotiate the cession treaty. He was commissioned as captain. Parks was a major landholder in both Westport, Missouri and in Shawnee, Kansas. He was also a Freemason and a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church. In Shawnee, Kansas, a Shawnee cemetery was started in the 1830s and remained in use until the 1870s. Parks was among the most prominent men buried there.[53]

In the 1853 Indian Appropriations Bill, Congress appropriated $64,366 for treaty obligations to the Shawnee, such as annuities, education, and other services. An additional $2,000 was appropriated for the Seneca and the Shawnee together.[54]

During the American Civil War, Black Bob's band fled from Kansas and joined the "Absentee Shawnee" in Indian Territory to escape the war. After the Civil War, the Shawnee in Kansas were expelled and forced to move to northeastern Oklahoma. The Shawnee members of the former Lewistown group became known as the "Eastern Shawnee".

The former Kansas Shawnee became known as the "Loyal Shawnee" (some say this is because of their allegiance with the Union during the war; others say this is because they were the last group to leave their Ohio homelands). The latter group appeared to be regarded as part of the Cherokee Nation by the United States. They were also known as the "Cherokee Shawnee" and were settled on some of the Cherokee land in Indian Territory.

Federal recognition

In the late 20th century, the "Loyal" or "Cherokee" Shawnee began a movement to be federally recognized as a tribe independent of the Cherokee Nation.[55] They received this action by a Congressional bill and are now known as the "Shawnee Tribe". Today, most members of the three federally recognized tribes of the Shawnee nation reside in Oklahoma.

Social and kinship groups

Before contact with Europeans, the Shawnee tribe had a patrilineal system, by which descent and inheritance went through paternal lines. This was different from many of the Native American tribes, who had matrilineal kinship systems. In that alternative, children were considered born to the mother's family and clan, and inheritance and property was passed through the female line.[56]

According to mid-19th century historian Henry Harvey, the Shawnee were ruled by kings, whom they called sachema [or sachems], who reigned by succession in the matrilineal line. For instance, the children of a king would not inherit the position. The sons of his brother, by the mother, or the sons of his sister (and after them, the sons of her daughter) would reign. Women did not inherit such a position directly. Harvey suggested that the Shawnee relied on this system of descent because a woman's sons would always be considered legitimate.[57]

The five divisions, or septs, of the tribe were commonly known as:

- Chillicothe (Principal Place), Chalahgawtha, Chalaka, Chalakatha; The Principal division of "Tschillicothi", appointed by the 1st Lead Illini or man Kwikullay.

- Hathawekela, Thawikila;

- Kispoko, Kispokotha, Kishpoko, Kishpokotha; [from ishpoko as akin to the Ispogi, meaning swamps or marshy lands of the Muscogi or Creeks, most specific to the Tukabatchi]

- Mekoche, Mequachake, Machachee, Maguck, Mackachack, etc.; Mackochee

- Pekowi, Pekuwe, Piqua, Pekowitha. [Pickywanni or pickquay]

The war chiefs were also hereditary. They descended from their maternal line in the Kispoko division.[23]

A 1935 study noted that the Shawnee had five septs, and that they were also divided among six clans or subdivisions, according to kinship. Each clan represented spiritual values and had a recognized role in the overall confederacy.[58] Each name group or clan is found among each of the five divisions, and each Shawnee belongs to a clan or name group.[58]

The six group names are:

- Pellewomhsoomi (Turkey name group)—represents bird life,

- Kkahkileewomhsoomi (Turtle name group)—represents aquatic life,

- Petekoθiteewomhsoomi (Rounded-feet name group)—represents carnivorous animals such as the dog, wolf, or those with paws that are ball-shaped or "rounded,"

- Mseewiwomhsoomi (Horse name group)—represents herbivorous animals such as the horse and deer,

- θepatiiwomhsoomi (Raccoon name group)—represents animals having paws which can rip and tear, such as those of a raccoon and bear.

- Petakineeθiiwomhsoomi (Rabbit name group)—represents a gentle and peaceful nature.[58]

Each sept or division had a primary village where the chief of the division lived. This village was usually named after the division. By tradition, each Shawnee division and clan had certain roles it performed on behalf of the entire tribe. By the time these kinship elements were recorded in writing by European Americans, these strong social traditions were fading. They are poorly understood. Because of the disruption and scattering of the Shawnee people from the 17th century through the 19th century, the roles of the divisions changed.

Today the United States government recognizes three Shawnee tribes, all of which are located in Oklahoma:

- The Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, consisting mainly of Hathawekela, Kispokotha, and Pekuwe divisions;

- The Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, mostly of the Mekoche division; and

- The Shawnee Tribe, formerly considered part of the Cherokee Nation, mostly of the Chaalakatha and Mekoche divisions. Petakineeθiiwomhsoomi (Rabbit name group) represents a gentle and peaceful nature, that stands alone as the Tail or last.

As of 2008, there were 7,584 enrolled Shawnee, with most living in Oklahoma.[59]

State-recognized tribe

The state of Alabama recognizes an organization, the Piqua Shawnee Tribe, as a state-recognized tribe under the Davis-Strong Act.[60][61] Ohio does not recognize any Shawnee tribes[62] or any other state-recognized tribes.[63] Kentucky also has no mechanism for state-recognizing tribes.[64]

Unrecognized groups who claim Shawnee descent

Numerous other groups claim Shawnee ancestry. These organizations are not federally recognized tribes[65] nor state-recognized tribes.[63]

The Absentee Shawnee Tribal Historic Preservation Office's Cultural Preservation Department wrote that "in our ancestral settlement areas including but not limited to Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, Indiana, [and] Alabama. In these areas, there are a number of people who claim Shawnee ancestry, this is not so much the concern as the fact that some of these individuals or groups use this claim to exploit Shawnee culture as a means of gaining opportunities for themselves from a public that is largely unaware of the vast divide that separates our tribal community politically and culturally from those of alleged Shawnee ancestry."[66]

These unrecognized organizations include:[67]

- Chickamauga Keetoowah Unami Wolf Band of Cherokee Delaware Shawnee of Ohio, West Virginia, and Virginia

- East of the River Shawnee, OH[66]

- Kispoko Sept of Ohio Shawnee, LA

- Kispoko Sept of Ohio Shawnee[66] (Hog Creek Reservation), OH

- Lower Eastern Ohio Mekoce Shawnee, OH. Letter of Intent to Petition 3/5/2001.[68][69][70][71]

- Lower Eastern Ohio Meckoche Shawnee, OH and WV[66]

- Morning Star Shawnee Nation, OH

- Ohio Blue Creek Bands, OH[66]

- Piqua Sept of Ohio Shawnee Indians, OH

- Platform Reservation Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation,[72][73] Nashville, IN

- Shawnee Nation Blue Creek Band, Adams County, OH. Letter of Intent to Petition 8/5/1998.[68][74]

- Piqua Shawnee Tribe / Piqua Sept of Ohio Shawnee Tribe, OH. Letter of Intent to Petition 04/16/1991.[68]

- Ridgetop Shawnee, Corbin, KY. In 2009 and 2010, the State House of the Kentucky General Assembly referred to the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians in House Joint Resolutions 15 or HJR-15 and HJR-16.[75][76]

- Southeastern Kentucky Shawnee, KY[66]

- United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation,[66] Bellefontaine, OH[77][78]

- United Shawnee Tribe, KS[66]

- Upper Kispoko Band of the Shawnee Indians, IN[66]

- Vinyard Indian Settlement of Shawnee Indians, Herod, IL[79]

- Youghiogheny River Band Of Shawnee Indians, Garrett County, MD[80]

Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe, has written: "Groups claiming to be tribal sovereigns has reached a new level of concern for the Shawnee Tribe and other tribal nations."[81] He continues:

There are currently 36 unestablished Shawnee “tribes” operating as 501(c)(3) non-profits across the country. Their 501(c)(3) designations allow them to solicit donations and participate in grants meant for Tribal nations. They pose as spokespeople for our ancestors at historic sites, state historical societies, and university campuses causing significant harm to our identity, culture, and reputation. These groups are violating the sacred, ancient places of our ancestors. They perform their ideas of our ceremonies on top of our burial mounds and have stolen our language, customs, and ceremonies.[81]

Flags of the Shawnee

Flag of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

Flag of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Flag of the Shawnee Tribe

Flag of the Shawnee Tribe

Notable historic Shawnee

Shawnee people from the 20th and 21st centuries are listed under their specific tribes.

- Big Hominy (Meshemethequater, 1690–1758), a respected warrior known for participating in peace conferences that prevented war between English settlers and the Shawnees

- Black Bob (Wawahchepaehai or Wawahchepaekar), 19th-century leader and war chief in Ohio

- Black Hoof (Catahecassa, 1740–1831), respected Shawnee chief who believed his people needed to adapt to European-American culture to survive.

- Black Snake (Peteusha) and Big Snake (Shemanetoo), active in Lord Dunmore's War, the American Revolutionary War, and the Northwest Indian War

- Blackfish (Chiungalla, 1729–1779), a Shawnee chief of the Chillicothe division of the Shawnee tribe.

- Blue Jacket (Waweyapiersenwaw, "Blue Jacket," 1743–1810), a leader in the Northwest Indian War and important early supporter of Tecumseh

- Peter Chartier (Wacanackshina, "White One Who Reclines" - 1690–1759), French-Canadian/Shawnee who opposed the sale of alcohol in Shawnee communities and fought on the side of the French in the French and Indian War.

- Chiksika (Chiuxca, "Black Stump," 1760–1792), Kispoko war chief and older brother of Tecumseh

- Cornstalk (Hokolesqua, 1720–1777), led the Shawnee in Dunmore's War of 1774.

- George Drouillard (1773–1810), French-Canadian/Shawnee who served as scout on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

- Kakowatcheky (d. ca. 1755),[82]: 500 a significant leader in 1694 and a Shawnee chief as early as 1709 who moved to Logstown in 1744.[83][84]

- Kekewepelethy (Captain Johnny, d. c. 1808), principal civil chief of the Shawnees in the Ohio Country during the Northwest Indian War

- Captain Logan (Spemica Lawba, "High Horn," c. 1776–1812), noted scout and interpreter on American side during the War of 1812

- Neucheconeh, (d. ca. 1748), chief of the western Pennsylvania Shawnee who campaigned against the unrestricted sale of alcohol in Shawnee communities.

- Nonhelema (1720–1786), sister of Cornstalk, helped compile the dictionary for the Shawnee language.

- Opessa Straight Tail (Wapatha, 1664–1750), became chief of his Pekowi band in 1697 and signed several peace treaties with William Penn before leading his people to the Ohio River Valley in ca. 1727

- Tecumseh (c. 1768–1813), Shawnee leader; with his brother Tenskwatawa attempted to unite tribes west of the Appalachians against the expansion of European-American settlement.

- Tenskwatawa ("The Open Door," 1775–1836), Shawnee prophet and younger brother of Tecumseh

See also

Notes

- Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. Archived February 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine 2008.

- Callender, "Shawnee," 623.

- "Algonquian, Algic". Ethnologue. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- Callender, "Shawnee," 623–24.

- Mahr, August C. (May 1960). "Shawnee Names and Migrations in Kentucky and West Virginia" (PDF). The Ohio Journal of Science. 60 (3): 155–158.

- Voegelin, Carl F. 1938–40. "Shawnee Stems and the Jacob P. Dunn Miami Dictionary." Indiana Historical Society Prehistory Research Series Volume 1, No. 8, Part III, p. 318 (October, 1939). Indianapolis.

- "Shawnee Myth. Story of a Year. Old Sawage and her Grandson." MS 3906, Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives. Myth collected by Jeremiah Curtin. 1850s–1880s.

- C. F. Voegelin, fieldwork notebook XII, "Big Sacred Lizard"; fieldwork 1933–34.

- Transcribed by Bruno Neti about 1951 from Shawnee Song cylinders collected by C. F. Voegelin and now in the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University. Sheet 8, Song 38.

- "maalaakwahi ke'neemepe: Shawnee Language Immersion Program (SLIP)". www.shawnee-nsn.gov. April 6, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Shawnee Language Collection". Sam Noble Museum. December 18, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Shawnee language, alphabet and pronunciation". omniglot.com. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Shawnee". Ethnologue. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples, p. 31. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover)

- Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background, p. 1. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2, 0-8214-0614-0

- Schutz, Noel W., Jr.: The Study of Shawnee Myth in an Ethnographic and Ethnohistorical Perspective, Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University, 1975.

- "Fort Ancient Earthworks". Ohio History Central. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Fort Ancient". www.ancientohiotrail.org. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Peregrine, Peter Neal; Ember, Melvin, eds. (2003). "Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 6: North America". Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Vol. 6 : North America. Springer Publishing. pp. 175–184. ISBN 0-306-46260-5.

- Drooker, Penelope B. (1997). The View from Madisonville: Protohistoric Western Fort Ancient Interaction Patterns. University of Michigan Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0915703425.

- Clark, Jerry. "Shawnees". Tennessee Encyclopedia of Culture and History. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- Charles Augustus Hanna, The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Volume 1, New York: Putnam's sons, 1911, esp. chap. IV, "The Shawnees", pp. 119–160.

- Kleber, John E. (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 815. ISBN 978-0-8131-2883-2. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, 1937, pp. 15–16; this account also appears in T.K. Cartmell's 1909 Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants p. 41.

- Edward Bland, The Discoverie of New Brittaine

- McWilliams, Richebourg; Iberville, Pierre (1991). Iberville's Gulf Journals. University of Alabama Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0817305390.

- Jerry E. Clark, The Shawnee, University Press of Kentucky, 1977. ISBN 0813128188

- Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717, p. 55. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-10193-7

- Not to be confused with the nearby French Margaret's Town; see John Franklin Meginness, Otzinachson: A History of the West Branch Valley of the Susquehanna (rev. ed., Williamsport, PA, 1889), 1:94. Ostonwakin is also spelled Otstonwakin.

- Stephen Warren, Worlds the Shawnees Made: Migration and Violence in Early America, UNC Press Books, 2014 ISBN 1469611732

- Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, pp. 16–17.

- Joseph Doddridge, 1850, A History of the Valley of Virginia, p. 44

- Calloway, Colin (2007). The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Viking. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-670-03862-6.

- Library of Congress, Transcript of the Journal of Nicholas Cresswell

- Gevinson, Alan. "Which Native American Tribes Allied Themselves with the French?" Teachinghistory.org, accessed September 23, 2011.

- Colin G. Calloway, "'We Have Always Been the Frontier': The American Revolution in Shawnee Country," American Indian Quarterly (1992) 16#1 pp 39–52. in JSTOR

- Owens, Robert M. (2007). Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 201–203. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8.

- Owens, p. 212

- Langguth, p. 164

- Langguth, p. 165

- Langguth, p. 166

- George Blanchard, Governor of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, so describes the meaning of the name in the PBS documentary We Shall Remain: Tecumseh's Vision Archived May 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine:

Well, I've always heard 'Teh-cum-theh'—'Teh-cum-theh'—means, in our culture and our belief, at nights when we see a falling star, it means that this panther is jumping from one mountain to another. And as kids, we saw these falling stars, we'd kind of hesitate about being out in the dark, because we thought there were actually panthers out there walking around. So that's what his name meant: Teh-cum-theh.

- Langguth, p. 168

- Funk, Arville (1983) [1969]. A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, Indiana: Christian Book Press.

- Langguth, p. 169

- Langguth, p. 167

- Jones, Charile (November 1987). "Sharing Choctaw History". Bishinik. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- Sherman, William Tecumseh. "H.B. Cushman, History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians (Greenville, Texas: 1899), 310 ff., quoted in "Survival Strategies"". Digital History. University of Houston. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- Turner III, Frederick (1978) [1973]. "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- "Kentucky: National Guard History eMuseum – War of 1812". Kynghistory.ky.gov. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- Lipscomb, Carol A.: Shawnee Indians from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- "Treaty with the Shawnee, 1825, Article 5, Page 264". Oklahoma State University. November 7, 1825. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Society, Kansas State Historical (March 27, 2019). Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society. The Kansas State Historical Society. p. 399 – via Internet Archive.

Joseph Parks Shawnee.

- "Indian Appropriation" (PDF). The New York Times. March 15, 1853. p. 3.

- "Text of S. 3019 (106th): Shawnee Tribe Status Act of 2000 (Introduced version)". GovTrack.us. Civic Impulse. September 7, 2000. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Harvey, Henry (1855). History of the Shawnee Indians: From the Year 1681 to 1854, Inclusive. Cincinnati: Ephraim Morgan & Sons. p. 18.

- Harvey, Henry (1855). "1". History of the Shawnee Indians: From the Year 1681 to 1854, Inclusive. Cincinnati: Ephraim Morgan & Sons. p. 18.

- Voegellin, C.F.; Voegelin, E. W. (1935). "Shawnee Name Groups". American Anthropologist. 37 (4): 617–635. doi:10.1525/aa.1935.37.4.02a00070.

- Oklahoma Indian Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. Archived February 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine 2008

- "Tribes". aiac.state.al.us.

- "State Recognized Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- Watson, Blake A. "Indian Gambling in Ohio: What are the Odds?" (PDF). Capital University Law Review 237 (2003) (excerpts). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

Ohio in any event does not officially recognize Indian tribes.

- "State Recognized Tribes". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- Pember, Mary Annette (June 21, 2021). "Shawnee reclaim the great Serpent Mound". ICT. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Indian Affairs Bureau (January 12, 2023). "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 88: 2112–16. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- "Tribal Historic Preservation Office, Cultural Preservation Department" (PDF). The Absentee Shawnee News. No. 11, Vol. 25. Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma. November 2010. p. 15. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- "SHAWNEE TODAY". Big Bear's Den. 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Ohio Indian Tribes". AAANativeArts.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Native American Peace Tree Ceremony guest is former Shawnee Chief". Eberly College of Arts and Sciences. West Virginia University. October 7, 2009. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Lower Eastern Ohio Mekoce Shawnee in Wilmington, Ohio (OH)". faqs.org, Tax-Exempt Organizations. 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "The Inter Tribal Learning Circle". Fort Ancient. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- Patricia Lowry (June 26, 2006). "Places: Near Fort Necessity, a National Road inn is reclaiming 1830s interior". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- Paul Johnson (January 22, 2008). "Native American Tribe Works Toward National Recognition". TheLedger.com. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Re: [NA-SHAWNEE] the Indiana Blue Creek Shawnee roll". RootsWeb: NA-SHAWNEE-L. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

There was no Blue Creek Band in Indiana...that's our Band here indigenous to Ohio...documented as late as 1870. You are looking for the Blue River Band.

- "Kentucky General Assembly 2010 Regular Session HJR-16". kentucky.gov, updated 9-2-2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- "Kentucky General Assembly 2009 Regular Session HJR-15". kentucky.gov, updated 5-2-2009. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- "American Indians in Ohio" Archived August 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Ohio Memory: An Online Scrapbook of Ohio History, The Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band, The Ohio Historical Society, retrieved September 30, 2007

- "Joint Resolution to recognize the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band" as adopted by the [Ohio] Senate, 113th General Assembly, Regular Session, Am. Sub. H.J.R. No. 8, 1979–1980

- "Vinyard Indian Settlement". GuideStar. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Lazarick, Len (November 25, 2021). "Native American Tribes Struggle for MD. Recognition". Maryland Reporter. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Barnes, Ben. "Appreciating and Protecting Federal Native Recognition". Indianz.com. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Mulkearn, Lois. George Mercer Papers: Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1954.

- Paul A. W. Wallace, Indians in Pennsylvania, DIANE Publishing Inc., 2007, p. 127. ISBN 1422314936

- Kakowatchiky

References

- Callender, Charles. "Shawnee", in Northeast: Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15, ed. Bruce Trigger. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978: 622–35. ISBN 0-16-072300-0

- Clifton, James A. Star Woman and Other Shawnee Tales. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984. ISBN 0-8191-3712-X; ISBN 0-8191-3713-8 (pbk.)

- Edmunds, R. David. The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- Edmunds, R. David. Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership. Originally published 1984. 2nd edition, New York: Pearson Longman, 2006. ISBN 0-321-04371-5

- Edmunds, R. David. "Forgotten Allies: The Loyal Shawnees and the War of 1812" in David Curtis Skaggs and Larry L. Nelson, eds., The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814, pp. 337–51. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6.

- Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2; ISBN 0-8214-0614-0 (pbk.)

- Lakomäki, Sami. Gathering Together: The Shawnee People through Diaspora and Nationhood, 1600–1870. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

- O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover).

- Sugden, John. Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Holt, 1997. ISBN 0-8050-4138-9 (hardcover); ISBN 0-8050-6121-5 (1999 paperback).

- Sugden, John. Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8032-4288-3.

External links

| Library resources about Shawnee |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911.

Federally recognized Shawnee tribes

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

- Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

Shawnee history

- Shawnee History Archived January 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Shawnee Indian Mission

- "Shawnee Indian Tribe", Access Genealogy

- Treaty of Fort Meigs, 1817, Central Michigan State University

- BlueJacket Archived January 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine