Japanese calligraphy

Japanese calligraphy (書道, shodō), also called shūji (習字), is a form of calligraphy, or artistic writing, of the Japanese language. Written Japanese was originally based on Chinese characters only, but the advent of the hiragana and katakana Japanese syllabaries resulted in intrinsically Japanese calligraphy styles.

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Styles

The term shodō (書道, "way of writing") is of Chinese origin and is widely used to describe the art of Chinese calligraphy during the medieval Tang dynasty.[1] Early Japanese calligraphy was originated from Chinese calligraphy. Many of its principles and techniques are very similar, and it recognizes the same basic writing styles:

- seal script (篆書 tensho) (pinyin: zhuànshū). The seal script (tensho) was commonly used throughout the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC) and the following Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) of China. After this time period, tensho style fell out of popularity in favor of reisho. However, tensho was still used for titles of published works or inscriptions. The clear and bold style of tensho made it work well for titles and this tradition of using tensho only for titles is still around today. By the time Chinese characters and calligraphy migrated over to Japan, tensho was already only used for titles and as a result, was never commonly used in Japan. In 57 AD, the Chinese emperor Guangwu of Han presented a golden seal to a king of a small region near what is now known as Fukuoka Prefecture. While this seal was not made in Japan, it is believed to be the first instance of tensho in Japan. The first work in Japan that actually utilized tensho was during the Nara period (646–794) was a six-paneled screen called the Torige Tensho Byobu. Each panel is divided into two columns and each column has eight characters. The screen speaks to a ruler and recommends that he use the counsel of wise ministers in order to rule justly.[2]

- clerical script (隷書 reisho) (pinyin: lìshū) The clerical script or scribe's script (reisho) is a very bold and commanding style of Chinese calligraphy; each of the strokes are greatly exaggerated at the beginning and end. It was most commonly used during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) and the term reisho had many significant meanings but is now only known as one of the five styles of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. Because of its bold style, the reisho technique is now reserved for large text applications such as plaques, signboards, titles of works, etc. This was its main purpose in Japan as well until the Edo period (1603–1868) when it was regarded as a calligraphic art form.[2][3]

- regular script (楷書 kaisho) (pinyin: kǎishū) The regular script or block script (kaisho) is fairly similar in function to that of Roman block capitals. While Japanese kaisho varies slightly from Chinese kaisho, it is primarily based on Chinese kaisho script in both form and function. The Japanese kaisho style was heavily influenced by the Sui dynasty (581–618) and the following Tang dynasty (618–907). Early examples of this style in Japan are mostly various statue and temple inscriptions. This was during the early Heian period (794–1185) and as time progressed there was a movement in Japan to become more culturally independent and a version of kaisho developed that became uniquely Japanese and included a little bit of the gyosho style. As its influence spread, the primary use of the kaisho technique was to copy the Lotus Sutra. There was a second wave of influence during the Kamakura (1192–1333) and Muromachi (1338–1573) periods, but this was mostly by Zen monks who used a technique based on Zen insight and is different from the classic kaisho technique.[2]

- semi-cursive (行書 gyōsho) (pinyin: xíngshū) The semi-cursive script (gyosho) means exactly what it says; this script style is a slightly more cursive version of kaisho script. This script was practiced at the same time as the reisho script. There are three different levels of "cursiveness" called seigyo, gyo, and gyoso. The style of gyosho utilizes a softer and more rounded technique, staying away from sharp corners and angles. In Japan many works were made using the gyosho technique during the early Heian period. Later in the Heian period, once Japan began to separate itself from China a Japanese version called wayo began to emerge. The Japanese version of gyosho became widely popular and became the basis of many schools of calligraphy. This was a result of gyosho meshing very well with both kanji and hiragana and writing with this technique was both natural and fluid.[2][3]

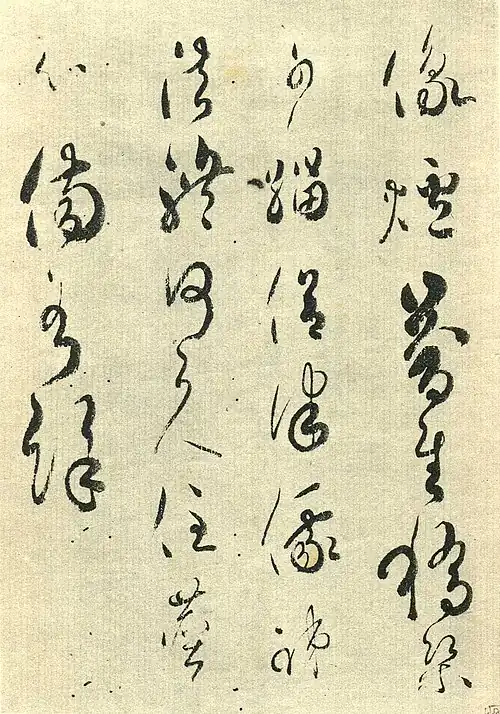

- cursive (草書 sōsho) (pinyin: cǎoshū). The cursive script (sosho) has its origins in the Han dynasty. It was used by scribes as a cursive version of reisho for taking notes. Early examples of sosho include inscriptions on bamboo and other wooden strips. This technique can be easily recognized by many strokes ending with a sweep to the upper right in a breaking-wave type form. As the Han dynasty came to an end, another version of sosho was developed, but this version was written slowly as opposed to the faster sosho that was popular until then. The exact date when sosho was introduced is unclear. Several texts from Japan shared many sosho-like techniques with Chinese texts during this time but it was not until Kukai, a famous Japanese Buddhist monk and scholar traveled to China during the early Heian period and brought back copies of texts that he made written in the sosho style.[2]

Tools

A number of tools are used to create a work of modern calligraphy.[4]

- The four most basic tools were collectively called the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝, bunbō shihō).

- A brush (筆, fude)

- An inkstick (墨, sumi).The hardened mixture of vegetable or pine soot and glue in the shape of a stick.[5] The best inksticks are between 50 and 100 years old.

- Mulberry paper (和紙, washi)

- An inkstone (硯, suzuri) to grind the inkstick against, mixed with water.

- Other tools include:

- A paper weight (文鎮, bunchin) to hold the paper in place

- A cloth (下敷き, shitajiki) to place under the paper (often newsprint is used as well) to prevent ink from bleeding through.

- A seal (印, in).[4] The art of engraving a seal is called "tenkoku" 篆刻. The student is encouraged to engrave his own seal. The position of the seal or seals is based on aesthetic preferences. One is not allowed to put a seal on calligraphy of a sutra.

During preparation, water is poured into the inkstone and the inkstick is ground against it, mixing the water with the dried ink to liquefy it. As this is a time-consuming process, modern-day beginners frequently use bottled liquid ink called Bokuju (墨汁, bokujū) . More advanced students are encouraged to grind their own ink. Paper is usually placed on a desk, while a large piece of paper may be placed on the floor or even on the ground (for a performance).

The brushes come in various shapes and sizes, and are usually made using animal hair bristles. Typical animal hair may come from goats, sheep, or horses. The handle may be made from wood, bamboo, plastic or other materials.[6]

History

Chinese roots

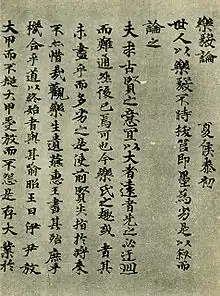

Written in the 7th century

The Chinese roots of Japanese calligraphy go back to the 13th century BC,[7] to the late Shang dynasty, a time when pictographs were inscribed on bone for religious purposes. When this writing developed into an instrument of administration for the state, the need for a uniform script was felt and Li Si, prime minister in the Chinese dynasty of Qin, standardized a script and its way of being written. He sanctioned a form of script based on squares of uniform size into which all characters could be written from eight strokes. He also devised rules of composition where horizontal strokes are written first and characters are composed starting from top to bottom, left to right. Because the symbols were inscribed with sharp instruments, the lines were originally angular; and in many ways, Li Si's achievements were made obsolete by the appearance of brush and ink (see Chinese calligraphy). The ink-wet brush creates a line quite different from a sharp stylus. It affords variation in thickness and curve of line. Calligraphy retained the block form of Li Si and his eight strokes, but the writer was free to create characters that emphasized aesthetically pleasing balance and form. The way a character was written gave a message of style.

Calligraphy in the Chinese tradition was thus introduced to Japan about AD 600 Known as the karayō (唐様) tradition, it has been practiced up to today, rejuvenated continuously through contact with Chinese culture.[8]

The oldest existing calligraphic text in Japan is the inscription on the halo of the Medicine Buddha statue in the Hōryū-ji Temple. This Chinese text was written in Shakyōtai (写経体) style, prominent in the Chinese Six Dynasties period.

Before the Nara period

The Hōryū-ji Temple also holds bibliographic notes on the Lotus Sutra: the Hokke Gisho (法華義疏) was written early in the 7th century and is considered the oldest Japanese text. It is written in Cursive script and illustrates that calligraphy in the Asuka period was already refined to a high degree.

The oldest hand-copied sutra in Japan is the Kongō Jōdaranikyō. Copied by the priest Hōrin in AD 686, the calligraphy style shows influences from the work of Ouyang Xun.

"Broken Stone in Uji Bridge" (宇治橋断碑, ujibashi danpi) (mid-7th century) and Stone in Nasu County "Stone in Nasu County" (那須国造碑, nasu kokuzō hi) are also typical examples from this time. Both inscriptions were influenced by the Northern Wei robust style.

In the 7th century, the Tang dynasty established hegemony in China. Their second Emperor Taizong esteemed Wang Xizhi's calligraphic texts and this popularity influenced Japanese calligraphers. All of the original texts written by Wang Xizhi have been lost, and copies such as Gakki-ron (楽毅論) written by the Empress Kōmyō are highly regarded as important sources for Wang Xizhi's style. However Wang's influence can barely be overstated, in particular for the wayō (和様) style unique to Japan: "Even today, there is something about Japanese calligraphy that retains the unchanged flavour of Wang Xizhi's style".[9]

Heian period

Emperor Kanmu moved the capital from Heijō-kyō in Nara, first to Nagaoka-kyō in 784, and then to Heian-kyō, Kyoto in 794. This marks the beginning of the Heian era, Japan's "golden age". Chinese influences in calligraphy were not changed in the early period. For example, under the Emperor Saga's reign, royalty, the aristocracy and even court ladies studied calligraphy by copying Chinese poetry texts in artistic style.

Wang Xizhi's influences remained dominant, which are shown in calligraphies written by Kūkai or Saichō. Some other Chinese calligraphers, such as Ouyang Xun and Yan Zhenqing were also highly valued. Their most notable admirers were Emperor Saga and Tachibana no Hayanari respectively.

At the same time, a style of calligraphy unique to Japan emerged. Writing had been popularized, and the kana syllabary was devised to deal with elements of pronunciation that could not be written with the borrowed Chinese characters. Japanese calligraphers still fitted the basic characters, called kanji (漢字), into the squares laid out centuries before. A fragment, Kara-ai no hana no utagire (韓藍花歌切, AD 749) is considered the first text to show a style unique to Japanese calligraphy; it shows a Tanka (短歌) poem using Man'yōgana, thus deviated from contemporary Chinese calligraphy. Ono no Michikaze (AD 894–966), one of the so-called sanseki (三跡, "Three Brush Traces"), along with Fujiwara no Sukemasa and Fujiwara no Yukinari, is considered the founder of the authentically Japanese wayō (和様) style, or wayō-shodō (和様書道). This development resonated with the court: Kūkai said to Emperor Saga, "China is a large country and Japan is relatively small, so I suggest writing in a different way." The "Cry for noble Saichō" (哭最澄上人, koku Saichō shounin), a poem written by Emperor Saga on the occasion of Saichō's death, was one of the examples of such a transformation. Ono no Michikaze served as an archetype for the Shōren-in school, which later became the Oie style of calligraphy. The Oie style was later used for official documents in the Edo period and was the prevailing style taught in the terakoya (寺子屋) schools of that time.

Kamakura and Muromachi period

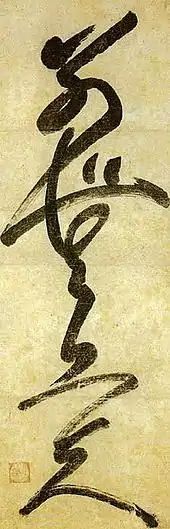

The ascension of Minamoto no Yoritomo to the title of shōgun, following the Hōgen and Heiji rebellions, and the victory of the Minamoto clan over the Taira, marked the beginning of the Kamakura period (AD 1185–1333), but not quite yet to a return to peace and tranquility. The era is sometimes called "the age of the warriors" and a broad transition from court influences to a leading role of the military establishment pervaded the culture. It is also, however, a time when exchanges with China of the Song dynasty continued and Buddhism greatly flourished. Zen monks such as Shunjo studied in China and the copybooks that he brought with him are considered highly influential for the karayō (唐様) tradition of the time, expressing a clear kaisho style.[10] But this was not the only example, indeed a succession of Chinese monks were naturalized at that time, encouraged by regent Hōjō Tokiyori. Rankei Doryū founded the Kenchō-ji temple in Kamakura and many of his works have been preserved. However, with the rise of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism a less technical style appeared, representative of Zen attitudes and exemplified in the works of Musō Soseki who wrote in a refined sosho style, or Shūhō Myōcho (1282–1337; better known as Daito Kokushi), the founder of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, who had not traveled to China to study. In terms of wayō (和様) style, the works of Fujiwara no Shunzei and Fujiwara no Teika are considered outstanding examples of the late Heian and early Kamakura.[11]

Political and military unrest continued throughout the Muromachi period (AD 1336–1537), characterized by tensions between imperial and civil authority and periods of outright civil war. However, as Ashikaga Takauji had ousted Emperor Go-Daigo from Kyoto to establish his own bakufu there, the intermingling of residual members of the imperial court, courtiers, daimyōs, samurai, and Zen priests resulted in vibrant cultural impulses. The arts prospered, but are not considered as refined as that of earlier times. Of note is the role of Ikkyū Sōjun, a successor of Shūhō Myōcho at Daitoku-ji; Ikkyū was instrumental in elevating the appreciation of calligraphy to an integral part of the tea ceremony in the 15th century.[12]

Edo period

Tokugawa Ieyasu centralized power in his shogunate between 1603 and 1615. This marked the beginning of the Edo period, which brought 250 years of relative stability to Japan, lasting until the second half of the 19th century. The period was marked by seclusion from overseas influences with the Sakoku (鎖国, "locked country" or "chained country") policy. Calligraphic studies were essentially limited to the study of karayō (唐様) style works, via Ming-dynasty China. Indigenous developments were contributed by Ingen and the Ōbaku sect of Zen buddhism, and the Daishi school of calligraphy. The latter focused on the study of the "eight principles of the character yong" (永字八法, eiji happō), which go back to Wang Xizhi, and the 72 types of hissei ("brush energy") expounded by Wang Xizhi's teacher, the Lady Wei. The 1664 reprint of a copybook based on these principles in Kyoto contributed an important theoretical development.[13] Calligraphers such as Hosoi Kotaku, who authored the five-volume Kanga Hyakudan in 1735, further advanced the karayō (唐様) style. Very characteristic for the early Edo period was an innovation by Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) who had paper made to order and painted a backdrop of decorative patterns, butterflies or floral elements that his calligraphy established a poetic correspondence with. Together with Konoe Nobutada (1565–1614) and Shōkadō Shōjō (1584–1639) – the three Kan'ei Sanpitsu (寛永三筆) – he is considered one of the greatest calligraphers in the wayō (和様) style at the time, creating examples of "a uniquely Japanese calligraphy".[14]

Around 1736 Yoshimune began relaxing Japan's isolation policy and Chinese cultural imports increased, in particular via the port of Nagasaki. Catalogues of imported copybooks testify to a broad appreciation of Chinese calligraphers among the Japanese literati who pursued the karayō style: "traditionalists" studied Wang Xizhi and Wen Zhengming, while "reformists" modeled their work on the sōsho style of calligraphers such as Zhang Xu, Huaisu and Mi Fu. In terms of wayō, Konoe Iehiro contributed many fine kana works but generally speaking, wayō style was not as vigorously practised as karayō at that time.[15] Nevertheless, some examples have been preserved by scholars of kokugaku (國學, National studies), or poets and painters such as Kaga no Chiyo, Yosa Buson or Sakai Hōitsu.

Meiji and modern period

In contemporary Japan, shodo is a popular class for elementary school and junior high school students. Many parents believe that having their children focus and sit still while practicing calligraphy will be beneficial.[16] In high school, calligraphy is one of the choices among art subjects, along with music or painting. It is also a popular high school club activity, particularly with the advent of performance calligraphy.[17] Some universities, such as University of Tsukuba, Tokyo Gakugei University and Fukuoka University of Education, have special departments of calligraphic study that emphasize teacher-training programs in calligraphy.

Connection to Zen Buddhism

Japanese calligraphy was influenced by, and influenced, Zen thought. For any particular piece of paper, the calligrapher has but one chance to create with the brush. The brush strokes cannot be corrected, and even a lack of confidence shows up in the work. The calligrapher must concentrate and be fluid in execution. The brush writes a statement about the calligrapher at a moment in time (see Hitsuzendō, the Zen way of the brush). Through Zen, Japanese calligraphy absorbed a distinct Japanese aesthetic often symbolised by the ensō or circle of enlightenment.

Zen calligraphy is practiced by Buddhist monks and most shodō practitioners. To write Zen calligraphy with mastery, one must clear one's mind and let the letters flow out of themselves, not practice and make a tremendous effort. This state of mind was called the mushin (無心, "no mind state") by the Japanese philosopher Nishida Kitaro. It is based on the principles of Zen Buddhism, which stresses a connection to the spiritual rather than the physical.[18]

Before Japanese tea ceremonies (which are connected to Zen Buddhism), one is to look at a work of shodō to clear one's mind. This is considered an essential step in the preparation for a tea ceremony.[18]

See also

- Fudepen – Modern stationery to write calligraphic scripts.

- List of National Treasures of Japan (writings)

- Sumi-e (Japanese ink painting) is related in method.

- Suzuri-bako (Japanese writing box)

- Barakamon – a manga based on Japanese calligraphy

Notes

- "Shodo and Calligraphy". Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- Nakata, Yujiro (1973). The art of Japanese calligraphy. Weatherhill. OCLC 255806098.

- Boudonnat, Louise Kushizaki, Harumi (2003). Traces of the brush : the art of Japanese calligraphy. Chronicle. ISBN 2020593424. OCLC 249566117.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yuuko Suzuki, Introduction to japanese calligraphy, Search Press, 2005

- "Tools of Japanese Calligraphy". Les Ateliers de Japon. Archived from the original on 2021-01-23. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- "About.com: Japanese Calligraphy Brushes". Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- in the late Shang dynasty. Claims of "28th century b.c." refer to the mythical Emperor Shen Nong (apprx. 2838–2698 BC) said to have used knot characters. This is not backed by scientific data.

- Nakata 1973, p. 145 ff.

- Nakata 1973, p. 170

- Nakata 1973, p. 153

- Nakata 1973, p. 166

- Nakata 1973, p. 156

- Nakata 1973, p. 157

- Nakata 1973, p.168

- Nakata 1973, p.169

- "Kanji History in Japan(2018)". Les Ateliers de Japon. Archived from the original on 2020-12-11. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- Inagaki, Naoto (January 29, 2012). "Performance calligraphy touches on essence of art form". Asahi Shinbun. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Solana Yuko Halada. "Shodo History". Japanese Calligraphy in Zen Spirit. Archived from the original on 2011-01-02.

References

- Nakata, Yujiro (1973). The Art of Japanese Calligraphy. New York/Tokyo: Weatherhill/Heibonsha. ISBN 0-8348-1013-1.

- History of Japanese calligraphy (和様書道史), Hachiro ONOUE (尾上八郎), 1934

- Yuuko Suzuki, Introduction to japanese calligraphy, Search Press, 2005.

External links

- Japanese Calligraphy 1950s Documentary on YouTube

- Shodo Journal Research Institute

- Shodo. Japanese calligraphy

- Brush Calligraphy Galleries

- Japanese Calligraphy galleries and more (hungarian language) Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- The History of Japanese Calligraphy In English, at BeyondCalligraphy.com

- Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Japanese calligraphy