Shoshoni language

Shoshoni, also written as Shoshoni-Gosiute and Shoshone (/ʃoʊˈʃoʊni/;[2] Shoshoni: soni' ta̲i̲kwappe, newe ta̲i̲kwappe or neme ta̲i̲kwappeh), is a Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan family, spoken in the Western United States by the Shoshone people. Shoshoni is primarily spoken in the Great Basin, in areas of Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and Idaho.[3]: 1

| Shoshoni | |

|---|---|

| Sosoni' ta̲i̲kwappe, Neme ta̲i̲kwappeh | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Idaho |

| Ethnicity | Shoshone people |

Native speakers | ~1,000 (2007)[1] 1,000 additional non-fluent speakers (2007)[1] |

Uto-Aztecan

| |

Early form | Proto-Numic

|

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | shh |

| Glottolog | shos1248 |

| ELP | Shoshone |

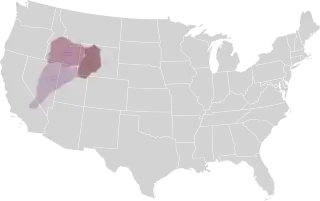

Map of the Shoshoni (and Timbisha) languages prior to European contact | |

Shoshoni is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The consonant inventory of Shoshoni is rather small, but a much wider range of surface forms of these phonemes appear in the spoken language. The language has six vowels, distinguished by length.[3]: 3 Shoshoni is a strongly suffixing language, and it inflects for nominal number and case and for verbal aspect and tense using suffixes. Word order is relatively free but shows a preference toward SOV order.[4]

The endonyms newe ta̲i̲kwappe and Sosoni' ta̲i̲kwappe mean "the people's language" and "the Shoshoni language," respectively.[5]: 5, 176 Shoshoni is classified as threatened, although attempts at revitalization are underway.[6]

Classification and dialects

Shoshoni is the northernmost member of the large Uto-Aztecan language family, which includes nearly sixty living languages, spoken in the Western United States down through Mexico and into El Salvador.[7] Shoshoni belongs to the Numic subbranch of Uto-Aztecan.[6] The word Numic comes from the cognate word in all Numic languages for "person". For example, in Shoshoni the word is neme [nɨw̃ɨ] or, depending on the dialect, newe [nɨwɨ], in Timbisha it is nümü [nɨwɨ], and in Southern Paiute, nuwuvi [nuwuβi].

Shoshoni's closest relatives are the Central Numic languages Timbisha and Comanche. Timbisha, or Panamint, is spoken in southeastern California by members of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe, but it is considered a distinct language from Shoshoni.[8] The Comanche split from the Shoshone around 1700, and consonant changes over the past few centuries have limited mutual intelligibility of Comanche and Shoshoni.[9]

Principal dialects of Shoshoni are Western Shoshoni in Nevada, Gosiute in western Utah, Northern Shoshoni in southern Idaho and northern Utah, and Eastern Shoshoni in Wyoming.[6] The main differences between these dialects are phonological.[3]: 1

Status

The number of people who speak Shoshoni has been steadily dwindling since the late 20th century. In the early 21st century, fluent speakers number only several hundred to a few thousand people, while an additional population of about 1,000 know the language to some degree but are not fluent.[6] The Duck Valley and Gosiute communities have established programs to teach the language to their children. Ethnologue lists Shoshoni as "threatened" as it notes that many of the speakers are 50 and older.[6] UNESCO has classified the Shoshoni language as "severely endangered" in Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.[10] The language is still being taught to children in a small number of isolated locations. The tribes have a strong interest in language revitalization, but efforts to preserve the language are scattered, with little coordination. However, literacy in Shoshoni is increasing. Shoshoni dictionaries have been published and portions of the Bible were translated in 1986.[6]

As of 2012, Idaho State University offers elementary, intermediate, and conversational Shoshoni language classes, in a 20-year project to preserve the language.[11] Open-source Shosoni audio is available online to complement classroom instruction, as part of the university's long-standing Shoshoni Language Project.[12][13]

The Shoshone-Bannock Tribe teaches Shoshoni to its children and adults as part of its Language and Culture Preservation Program.[14] On the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, elders have been active in digital language archiving. Shoshoni is taught using Dr. Steven Greymorning's Accelerated Second Language Acquisition techniques.[15]

A summer program known as the Shoshone/Goshute Youth Language Apprenticeship Program (SYLAP), held at the University of Utah's Center for American Indian Languages since 2009, has been featured on NPR's Weekend Edition.[16][17][18] Shoshoni youth serve as interns, assisting with digitization of Shoshoni language recordings and documentation from the Wick R. Miller collection, in order to make the materials available for tribal members.[16] The program released the first Shoshone language video game in August 2013.[19]

In July 2012, Blackfoot High School in Southeastern Idaho announced it would offer Shoshoni language classes. The Chief Tahgee Elementary Academy, a Shoshone-Bannock charter school teaching English and Shoshoni, opened at Fort Hall in 2013.[20][21]

Phonology

Vowels

Shoshoni has a typical Numic vowel inventory of five vowels. In addition, there is the common diphthong /ai/, which functions as a simple vowel and varies rather freely with [e]; however, certain morphemes always contain [ai] and others always contain [e]. All vowels occur as short or long, but [aiː]/[eː] is rare.[3]: 3

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| High | short | i | ɨ | u |

| long | iː | ɨː | uː | |

| Mid | short | ai | o | |

| long | aiː | oː | ||

| Low | short | a | ||

| long | aː | |||

Consonants

Shoshoni has a typical Numic consonant inventory.

| Bilabial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Stop | p | t | k | kʷ | ʔ | |

| Affricate | t͡s | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Semivowel | j | w | ||||

Syllable structure

Shoshoni syllables are of the form (C)V(V)(C). For instance: nɨkka "dance" (CVC CV), ɨkkoi "sleep" (VC CVV), and paa "water" (CVV). Shoshoni does not allow onset clusters.

Typical Shoshoni roots are of the form CV(V)CV(V).[22] Examples include kasa "wing" and papi "older brother."

Stress

Stress in Shoshoni is regular but not distinctive. Primary stress usually falls on the first syllable (more specifically, the first mora) of a word; however, primary stress tends to fall on the second syllable if that syllable is long.[3]: 11 For instance, natsattamahkantɨn [ˈnazattamaxandɨ] "tied up" bears primary stress on the first syllable; however, kottoohkwa [kotˈtoːxˌwa] "made a fire" bears primary stress on the second syllable, with long vowel [oː], instead of the first syllable with short vowel [o].

As in other Numic languages, stress in Shoshoni is distributed based on mora-counting. Short Shoshoni vowels have one mora, while long vowels and vowel clusters ending in [a] have two morae. Following the primary stress, every other mora receives secondary stress. If stress falls on the second mora in a long vowel, the stress is transferred to the first mora in the long vowel and mora counting continues from there. For example, natsattamahkantɨn "tied up" bears the stress pattern [ˈnazatˌtamaˌxandɨ], with stress falling on every other mora.

With some dialectical variation, mora counting resets at the border between stems in compound words. Final syllables need not be stressed and may undergo optional final vowel devoicing.[3]: 11

Phonological processes

Given here are a few examples of regular, well-documented phonological rules in Shoshoni:[3]: 3–9

- Short, unclustered, unstressed vowels, when part of final syllables and followed by /h/, are devoiced. These same vowels, when preceded by /h/, are usually devoiced. These processes represent Shoshoni "organic devoicing." For instance, tɨkkahkwan → [tɨkkḁxwa] "ate up".

- Final vowels may be devoiced optionally, representing Shoshoni "inorganic devoicing." If the final vowel is devoiced, the long or short consonant preceding it is also devoiced. Thus, kammu → [kamm̥u̥] "jackrabbit".

- Stops, affricates, and nasals are voiced and lenited between vowels. The stops and affricate become voiced fricatives; the nasals become nasalized glides. Thus papi → [paβi] "brother", tatsa → [taza ~ tad͡za] "summer," and imaa → [iw̃aː] "tomorrow".

- Stops, affricates, and nasals are lenited, but remain unvoiced, when they are preceded by underlying /h/. This /h/ is deleted in the surface form. Thus, paikkahkwa → [pekkḁxwa] "killed".

- Stops, affricates, and nasals are voiced when part of an intervocalic nasal cluster. Thus, pampi → [pambi] "head" and wantsi → [wand͡zi] "antelope".

Morphology

Shoshoni is a synthetic, agglutinative language, in which words, especially verbs, tend to be complex with several morphemes strung together. Shoshoni is a primarily suffixing language.

Absolutive suffixes

Many nouns in Shoshoni have an absolutive suffix (unrelated to the absolutive case). The absolutive suffix is normally dropped when the noun is the first element in a compound, when the noun is followed by a suffix or postposition, or when the noun is incorporated into a verb. For instance, the independent noun sɨhɨpin "willow" has the absolutive suffix -pin; the root loses this suffix in the form sɨhɨykwi "to gather willows". The correlation between any particular noun stem and which of the seven absolutive suffixes it has is irregular and unpredictable. The absolutive suffixes are as follows:[3]: 16

- -pin

- -ppɨh

- -ppɨ

- -pittsih, -pittsɨh

- -mpih

- -pai

- -ttsih

Number and case

Shoshoni is a nominative-accusative language. Shoshoni nouns inflect for three cases (subjective, objective, and possessive) and for three numbers (singular, dual, and plural).

Number is marked by suffixes on all human nouns and optionally on other animate nouns. The regular suffixes for number are listed in the table below. The Shoshoni singular is unmarked.[3]: 26

| Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| Case | Subjective | Ø | -nɨwɨh | -nɨɨn |

| Objective | Ø | -nihi | -nii | |

| Possessive | Ø | -nɨhɨn | -nɨɨn | |

Case is also marked by suffixes, which vary depending on the noun. Subjective case is unmarked. Many nouns also have a zero objective case marker; other possible objective markers are -tta, -a, and -i. These suffixes correspond with the possessive case markers -n, -ttan or -n, -an, or -n (in Western Shoshoni; this last suffix also appears as -an in Gosiute and is replaced by -in in Northern Shoshoni). These case markers can be predicted only to a degree based on phonology of the noun stem.[3]: 27

Derivational morphology

Nominal derivational morphology is also often achieved through suffixing. For instance, the instrumental suffix -(n)nompɨh is used with verb stems to form nouns used for the purpose of the verb: katɨnnompɨh "chair" is derived from katɨ "sit"; puinompɨh "binoculars" is derived from pui "see".[3]: 17 The characterization suffix -kantɨn be used with a root noun to derive a noun characterized by the root: hupiakantɨn "singer" is derived from hupia "song"; puhakantɨn "shaman" is derived from puha "power", as one characterized by power.[3]: 18

Number

Shoshoni verbs may mark for number, mainly through reduplication or suppletion. The dual is commonly marked through reduplication of the first syllable of the verb stem, so that singular kimma "come" becomes kikimma in the dual (and remains kima in the plural). A suppletive form is often used for the dual or plural forms of the verb; for instance, singular yaa "carry" becomes hima in both the dual and plural. Suppletion and reduplication frequently work in tandem to express number: singular nukki "run" becomes the reduplicated nunukki in the dual and the suppleted nutaa in the plural; singular yɨtsɨ "fly" is reduplicated, suppleted dual yoyoti and suppleted plural yoti.[3]: 39

Instrumental prefixes

Shoshoni uses prefixes to add a specific instrumental element to a verb. For instance, the instrumental prefix to"- "with the hand or fist" can be used with the verb tsima "scrape" to yield tottsima "wipe," as in pɨn puihkatti tottsimma yakaitɨn "he wiped at his eyes, crying".[3]: 48

Common instrumental prefixes include:[3]: 46–7

- kɨ"- "with the teeth or mouth"

- ku"- "by heat"

- ma- "with a non-grasping hand"

- mu"- "with the nose or front of body"

- ni"- "with the voice"

- pi"- "with the buttocks or back of body"

- sɨ"- "by cold"

- sun- "with the mind"

- ta"- "with the feet"

- ta"- "with a hard instrument or rock"

- to"- "with the hand or fist"

- tsa"- "with a grasping hand"

- tsi"- "with a sharp point"

- tso"- "with the head"

- wɨ"- "with a long instrument or body"; generic instrumental

Syntax

Word order

Subject-object-verb (SOV) is the typical word order for Shoshoni.[5]: 32–3 [3]: 75

nɨ

I

hunanna

badger

puinnu

see

"I saw a badger"

In ditransitive sentences, the direct and indirect object are marked with the objective case. The indirect object can occur before the direct object, or vice versa. For example, in nɨ tsuhnippɨha satiia uttuhkwa "I gave the bone to the dog", tsuhnippɨh "bone" and satii "dog" take the objective case suffix -a.[3]: 76

The subject is not a mandatory component of a grammatical Shoshoni sentence. Therefore, impersonal sentences without subjects are allowed; those sentences have an object-verb word order.[23]

ɨtɨinna

hot-CONT

"it [the weather] is hot" [3]: 83

In particular, it is common for the subject to be deleted when a coreferential pronoun appears elsewhere in the sentence. For example, pɨnnan haintsɨha kai paikkawaihtɨn "he won't kill his (own) friend" uses the coreferential possessive pronoun pɨnnan and lacks a word for "he" as an explicit subject.[3]: 77 Likewise, the subject can be deleted from the sentence when the subject can be inferred from context. For example, in a narrative about one man who shoots another, u paikkahkwa "he killed him" (literally, "him killed") is acceptable, because the killer is clear from the context of the narrative.[3]: 77

State-of-being sentences express “be” by excluding an overt verb, resulting in a basic subject-object order.

Sentence meaning is not dependent on word order in Shoshoni.[5]: 32–33 For example, if the subject is an unstressed pronoun then it is grammatical for the subject to follow the object of the sentence.[23]

Constituent order

The basic order of constituent morphemes in Shoshoni verbs is as follows:

(Valence) - (Instrumental) - Stem - (Causative/Benefactive) - (Secondary Verb) - (Directional) - (Prefinal Aspect) - (Aspect) - (Imperative) - (Number) - (Subordination)

Any verb form must include a verb stem, but other prefixes and suffixes may not be present, depending on the particular verb form.[3]: 42

Relative clauses

Relative clauses tend to share the same head noun as the main clause, and the case of this noun must agree in both clauses. When the subject of the relative clause matches the subject of the main clause, the verb of the relative clause takes on the same-subject subordination suffix -tɨn or -h/kkantɨn, depending on whether the events of the clauses occur simultaneously or not. These suffixes agree with the head noun of the main clause in both case and number.[3]: 61 For example, wa'ippɨ yakaitɨn pitɨnuh "the woman who was crying arrived," where the subject wa'ippɨ "woman" is the same for both clauses and yakai- "cry" in the relative clause takes the suffix -tɨn.[3]: 61

However, when the subject of the relative clause is not the head noun of the main clause, the subject of the relative clause takes the possessive case and a different set of verbal suffixes are used; the head noun may be deleted from the relative clause altogether. These different-subject subordinate suffixes also mark verb tense and aspect: in the nominative case, they are -na if present, -h/kkan if stative, -h/kkwan if momentaneous, -ppɨh if perfect, -tu'ih if future, and -ih if unmarked.[3]: 62

aitɨn

this

painkwi

fish

nɨhɨn

our

tɨkkanna

eating

pitsikkammanna

tastes-rotten

"this fish that we are eating tastes rotten"

The subject "we" of the relative clause appears as the possessive pronoun nɨhɨn "our," and tɨkka- "eat" takes the suffix -nna to indicate the present action of eating.[3]: 62

Switch reference

Shoshoni exhibits switch reference, in which a non-relative, subordinate clause is marked when its subject is a pronoun that differs from the subject of the main clause. In such subordinate clauses, the subject takes the objective case and the verb takes on a switch reference suffix: -ku if the events of both clauses occur simultaneously, -h/kkan if the events of the subordinate clause occur first, or the combined -h/kkanku if the events of the subordinate clause occur over an extended amount of time.[3]: 66 For example, sunni naaku wihyu nɨnɨttsi utɨɨkatti tattɨkwa "when that happened, something scary came to them." In the relative clause sunni naaku "when that happened", the verb naa- "be" or "happen" takes on the suffix -ku to indicate that the relative and main clauses co-occur in the narrative.[3]: 67

Writing system

Shoshoni lacks a single agreed-upon writing system. Multiple orthographies exist, with differing levels of acceptance among Shoshoni speakers. Among the Shoshone, there are conflicting views on whether Shoshoni should be written at all.

Traditionalists advocate to keep Shoshoni an oral language, better protected from outsiders who might exploit the language. Meanwhile, progressives argue that writing the language down will better preserve it and make it useful today.[24]

The older Crum-Miller system and the Idaho State University system (or Gould system) are the two main Shoshoni writing systems in use.[25][26][27][28]

The Crum-Miller orthography was developed in the 1960s by Beverly Crum, a Shoshone elder and linguist, and Wick Miller, a non-Native anthropologist and linguist. The system is largely phonemic, with specific symbols mapping to specific phonemes, which reflects the underlying sounds but not necessarily surface pronunciations.[24][5]: 10

| Letter | IPA |

|---|---|

| aa | ɑː |

| a | ɑ |

| a̲i̲ | e |

| ai | a͡ɪ |

| e | ɨ |

| ee | ɨː |

| h | h |

| k | k~ɣ~g |

| kk | kː |

| hk | x |

| kw | kʷ~ɣʷ~gʷ |

| kkw | kːʷ |

| hkw | xʷ |

| m | m |

| mm | mː |

| n | n |

| nn | nː |

| o | o |

| oo | oː |

| p | p~β~b |

| pp | pː |

| hp | ɸ |

| s | s |

| is | ʃ |

| t | t~d~ɾ |

| it | ð |

| tt | tː |

| iht | θ |

| ts | t͡s~z |

| its | ʒ |

| tts | tt͡s |

| itts | t͡ʃ |

| u | u |

| uu | uː |

| w | w |

| y | j |

| ' | ʔ |

The newer Idaho State system was developed by the Shoshone elder Drusilla Gould and the non-Native linguist Christopher Loether and is used more commonly in southern Idaho.[24] Compared to the Crum-Miller system, the Idaho State system is more phonetic, with spellings more closely reflecting the surface pronunciations of words, but it lacks the deeper phonemic information that the Crum-Miller system provides.[5]: 10

Online Shoshoni dictionaries are available for everyday use.[29]

See also

- Shoshone people

- Shoshonean languages

- Timbisha language

- Comanche language

- Sacagawea, the Shoshone woman who translated for Lewis and Clark

References

- Shoshoni at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Bauer, Laurie. (2007). The Linguistics Student’s Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- McLaughlin, John E. (2012). Shoshoni Grammar. Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 9783862883042. OCLC 793217272.

- "WALS Online - Language Shoshone". The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Gould, Drusilla; Loether, Christopher (2002). An Introduction to the Shoshoni Language: Dammen Da̲igwape. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874807301. OCLC 50114343.

- "Shoshoni". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- "Summary by language family". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Uto-Aztecan Language Family | About World Languages". aboutworldlanguages.com. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- McLaughlin, John E. (1992). "A Counter-Intuitive Solution in Central Numic Phonology". International Journal of American Linguistics. 58 (2): 158–181. doi:10.1086/ijal.58.2.3519754. S2CID 148250257.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- "Native American Academic Services – Diversity Resource Center". Idaho State University. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- "Idaho State University Shoshoni Language Project still going strong after 20 years". Idaho State University. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- "An Introduction to the Shoshoni Language : University Press Catalog". Utah University Press. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- "Language and Culture Preservation Program". Shoshone-Bannock tribe. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- Dunlap, Tetona (2012-02-28). "As elders pass, Wind River Indian Reservation teachers turn to technology to preserve Shoshone language". WyoFile. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Shoshone/Goshute Youth Language Apprenticeship Program". Center for American Indian Languages, University of Utah. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Koepp, Paul (2010-07-21). "University of Utah program helps Shoshone youths keep language alive". Deseret News. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Brundin, Jenny (2009-07-18). "Ten Teens Study To Guard Their Native Language". Morning Edition, NPR. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "First Shoshone Language Video Game". ScienceBlog.com. 2013-08-14. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- "Idaho district to offer Shoshoni classes". Deseret News. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- Cosgrove, Liz (2013-05-31). "New charter school in Fort Hall". KIFI. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- Shaul, David Leedom (2012). Survey of Shoshone Grammar with Reference to Eastern Shoshone. National Science Foundation. p. 13.

- Shaul, David (2012). Survey of Shoshone Grammar with Reference to Eastern Shoshone. National Science Foundation. pp. 112–113.

- Broncho, Samuel (2016-12-16). "How do you learn a language that isn't written down?". British Council. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- Miller, Wick R. (1972). Newe Natekwinappeh: Shoshoni Stories and Dictionary. University of Utah Anthropological Papers 94. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Crum, Beverly; Dayley, Jon P. (1993). Western Shoshoni Grammar. Boise State University Occasional Papers and Monographs in Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics Volume No. 1. Boise, Idaho: Department of Anthropology, Boise State University. ISBN 978-0-9639749-0-7.

- Crum, Beverly; Dayley, Jon P. (1997). Shoshoni Texts. Occasional Papers and Monographs in Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics Volume No. 2. Boise, Idaho: Department of Anthropology, Boise State University.

- Crum, Beverly; Crum, Earl; Dayley, Jon P. (2001). Newe Hupia: Shoshoni Poetry Songs. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

- "Shoshoni Dictionary | Shoshoni Language Project". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

External links

- Shoshoni Language Project - Project for Shoshoni language revitalization at the University of Utah

- The Enee Game - Shoshone language video game

- Shoshoni Swadesh vocabulary list (Wiktionary)

- Portions of the Book of Common Prayer in Shoshoni Translated by Charles Lajoe and the Reverend John Roberts (Wind River Reservation, Wyoming: no publisher, 1899) digitized by Richard Mammana

- Open source audio for introductory Shoshoni course, (via links to iTunesU)

- Shoshoni Online Dictionary

- OLAC resources in and about the Shoshoni language

- Shoshoni language program at Idaho State University