Siberian Ingrian Finnish

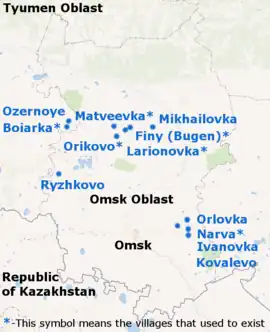

Siberian Ingrian Finnish (Russian: Сибирский ингерманландский идиом) is a Lower Luga Ingrian Finnish – Lower Luga Ingrian (Izhorian) mixed language.[2][3] The ancestors of the speakers of this language migrated from the Rosona River area to Siberia in 1803–1804. Most native speakers of this language live in Ryzhkovo or nearby, as well as in Omsk and Tallinn (Estonia).

| Siberian Ingrian Finnish | |

|---|---|

| mejjen kiel', oma kiel', suomen kiel' | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Western Siberia |

| Ethnicity | Siberian Finns, Estonians |

Native speakers | At least 15, may know ~ 100 (2022)[1] |

| Latin, Cyrillic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | sibe1253 |

Settlements where Siberian Ingrian Finnish speakers lived or still live now (2022) | |

History

In the autumn of 1802, due to disobedience to their landowners, several dozen people with their families from the villages of Vanakülä, Malaya Arsiya, Bolshaya Arsiya, Volkovo, Mertvitsa, Fedorovka and Variva were exiled to Siberia.[4][5] They arrived in the Kamyshinskaya volost of the Tobolsk Governorate in 1804.[6]

When the settlers founded the village, the first name of this settlement was Chukhonskaya village (Russian: деревня Чухонская).[7] The settlement also became known as Ryzhkovo (Russian: Рыжково). Here, Siberian Ingrian Finnish as a language of communication was formed based on the Ingrian Finnish and Ingrian dialects of the villages of the lower reaches of the Luga River among migrants in the first decades of the 19th century.[8]

In the second half of the 1840s, Ryzhkovo became a place of exile for people of the Lutheran confession. In April 1846, there was a fire in Ryzhkovo. After the fire, 20 families of Ingrian Finns moved north to the Tara Uezd of the Tobolsk Governorate. Here on the Bugen River, among forests and swamps, they founded a settlement named Bugene. In the future, this settlement was called Finy. In the vicinity of Bugene, by the end of the 19th century, 3 villages (Orikovo, Matveevka (Välikülä), Larionovka (Unkurin külä)) appeared, which were founded by the Ingrian Finns.

In 1849, another group of Ingrian Finns from Ryzhkovo in the Panovskaya volost, west of Ryzhkovo, founded the village of Boiarka. A new Lutheran colony (Om' koloniya) appeared on the banks of the Om River, in 1863. The following villages were part of this colony: Staraya Riga village, Stary Revel village (Viron külä), Gelsingfors (Ruotsin külä), Narva village (Suomen külä). The village of Narva was meant for the Ingrian Finns from Ryzhkovo. Settlers from the Ingrian Finnish village of Narva in 1895 founded the village of Ivanovka.

The Siberian Ingrian Finnish speakers made rather long migrations in Siberia. In the 19th century, part of the Siberian Ingrian Finnish speakers migrated to a distance of two thousand kilometers to the village of Verkhny Suetuk beyond the river Yenisey (now Krasnoyarsk Krai), and Ingrian peasants from the village of Finy founded a settlement not far from Altai, on the banks of the Kulunda River, 500 km from Omsk.[9]

History of studying Siberian Ingrian Finnish

The first mentions of the exiles from western Ingria and about their first colony - the village of Ryzhkovo appeared in the two articles in 1844[10] and in 1846[11] in the newspaper "Maamiehen Ystävä", which was published in the Grand Duchy of Finland. Matthias Castrén's article[12] was one of the first publications about the exiled Finns in Siberia. In this article, Ingrian Finns were also mentioned. The next publication was a book of memoirs[13] by the Lutheran pastor Johannes Granö, who lived and worked in the Finnish settlements in Siberia at the end of the 19th century. The historiographic description of the Siberian Finnish settlements was continued by the sons of pastor Granö, Johannes Gabriel Granö[14] and Paavo Granö.[15][16] From the second half of the 20th century to the beginning of the 21st century, appeared several publications by Finnish researchers (Alpo Juntunen,[17][18] Juha Saari,[19] Max Engman[20]) based on documents from the Finnish archives about the Lutherans exiled to Siberia.

In 1968–1969, the only expedition to Siberian Finnish settlements to study Siberian Finnish dialects was made by Vieno Zlobina from the Petrozavodsk State University.[21][22][23][24] The Finnish researcher Ruben Nirvi got acquainted with Zlobina's Siberian language materials and made more accurate conclusions[21][25] about the Siberian Ingrian Finnish language. Information about the Siberian Finns is also in the publications of Estonian scientists (Jüri Viikberg,[26][27] Anu Korb,[28][29][30] Aivar Jürgenson[31][32][33][34]).

A detailed study of the Siberian Ingrian Finnish language was begun at the beginning of the 21st century by Russian scientists. Daria Sidorkevich from the Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences researched and documented the Siberian Ingrian Finnish language in 2008 - 2014.[3][35] A PhD thesis[2] about the language was written by Daria Sidorkevich in 2013 - 2014. The Siberian Ingrian Finnish language was also researched and documented by Mehmet Muslimov from the Institute for Linguistic Studies of the RAS, Fedor Rozhanskiy from the University of Tartu and Natalia Kuznetsova[36][37] from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

Name

The term Siberian Ingrian Finnish (Russian: Сибирский ингерманландский идиом) for the language of the descendants of settlers from Ingria was introduced by Russian linguists and appeared in Sidorkevich's scientific works.[2][3] Natalia Kuznetsova uses a similar term in her articles: "Siberian Ingrian/Finnish" or "the mixed Siberian Ingrian/Finnish variety".[36][37] The Glottolog language database also uses the name Siberian Ingrian Finnish.[38]

Vieno Zlobina in her articles[23][24] introduced the term "корлаки" or "korlakat" (English: Korlaks) to refer to a group of people using the Siberian Ingrian Finnish language. Currently, this name is known and used in Finland. From this name came one of the names of this language: language of Korlaks (Russian: корлакский язык, Finnish: korlakan kieli). The speakers of Siberian Ingrian Finnish have never used the name "корлаки" or "korlakat" (English: Korlaks) as a self-name[39] (although some speakers knew the term[40]).

Phonology

Vowels

The Siberian Ingrian Finnish language has the following vowels:[41]

| Front | Central | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | unrounded | i | ii | ||||

| rounded | ü | üü | u | uu | |||

| Mid | unrounded | e | ee | ə | ɨ | ||

| rounded | ö | o | |||||

| Open | unrounded | ä | ää | a | aa | ||

Diphthongs

The number of diphthongs in Siberian Ingrian Finnish is less than in Votic, some dialects of Ingrian (Izhorian), Estonian and Finnish. Diphthongs of Siberian Ingrian Finnish are shown in the table:[42]

| i | a | o | u | ä | ö | ü | e | ə | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | ia sial pig.ALL/ADE |

io sion tie.IPF.1SG |

iu hius hair |

* | * | * | * | iə tiə road | |

| a | ai maitᵒ milk |

ao maot worm.PL |

au laula song.PRT |

ae laen ceiling.GEN |

* | ||||

| o | oi koir dog |

oa soan war.GEN |

ou loun lunch (dinner) |

oe joen river.GEN |

* | ||||

| u | ui luin read.IPF.1SG |

ua tuan hut.GEN |

* | ue luen read.PRS.1SG |

uə suəl' salt | ||||

| ä | äi jäi stay.IPF.3SG |

äö näöt face.PL |

äü käüp walk(go).PRS.3SG |

äe näet see.PRS.2SG |

|||||

| ö | öi löin beat.IPF.1SG |

* | öü höür' steam (vapor) |

* | * | ||||

| ü | üi püis catch.IPF.3SG |

üä süän heart |

* | * | üə hüə 3PL | ||||

| e | ei keitin cook.IPF.1SG |

* | * | eu neulᵊ needle |

* | * | * | ||

| ə | |||||||||

| ɨ |

Within a diphthong, a combination of front and back vowels is unacceptable (a, o, u vs. ä, ö, ü), except for the vowels: i and e, which can combine with both front vowels and back vowels.[42] The symbol "*" in the table above means that these diphthongs are theoretically possible in Siberian Ingrian Finnish, but the words containing these sounds have not yet been found in the audio data.[43] The gray color in the cells of the table means that such a combination of vowels in diphthongs is completely impossible.

Consonants

The consonant inventory of Siberian Ingrian Finnish is distinguished by a large number of various phonemes that appeared in the language as a result of the reduction of vowels and as a result of borrowings from other languages. The Siberian Ingrian Finnish language has the following consonant sounds:[44]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | ||

| Voiceless plosives | singleton | p | p' | t | t' | k | k' | ||

| geminate | pp | pp' | tt | tt' | kk | kk' | |||

| Voiced plosives | singleton | b | b' | d | d' | g | g' | ||

| geminate | bb | * | dd | dd' | gg | * | |||

| Nasal | singleton | m | m' | n | n' | ||||

| geminate | mm | mm' | nn | nn' | |||||

| Voiceless fricatives | singleton | f | f' | s | s' | š | š' | h | h' |

| geminate | ff | ss | ss' | * | šš' | hh | * | ||

| Voiced fricatives | singleton | v | v' | z | z' | ž | * | ||

| geminate | vv | vv' | zz | * | žž | * | |||

| Affricate | singleton | č | * | ||||||

| geminate | čč | ||||||||

| Lateral approximants | singleton | l | l' | ||||||

| geminate | ll | ll' | |||||||

| Central approximants | singleton | r | r' | j | * | ||||

| geminate | rr | rr' | jj | * | |||||

Additional series of consonant sounds

These consonant sounds appear in word-final position. The appearance of these consonant sounds is the result of vowel reduction in word-final position. Siberian Ingrian Finnish has the following additional series of consonant sounds:[45]

- Aspirated consonant sounds - " ᵊ ", at this moment, aspiration appears unstable.

- Palatalized consonant sounds - " ' ".

- Labialized consonant sounds - " ᵒ ".

- Palatalized and labialized consonant sounds - " 'ᵒ ".

The additional series of consonant sounds are shown in the table:[46]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asp. | pal. | lab. | pal. and lab. | asp. | pal. | lab. | pal. and lab. | asp. | pal. | lab. | pal. and lab. | asp. | pal. | lab. | pal. and lab. | ||

| Voiceless plosives | singleton | pᵊ | p' | pᵒ | p'ᵒ | tᵊ | t' | tᵒ | t'ᵒ | kᵊ | k' | kᵒ | k'ᵒ | ||||

| geminate | * | pp' | ppᵒ | * | ttᵊ | tt' | ttᵒ | tt'ᵒ | kkᵊ | kk' | kkᵒ | kk'ᵒ | |||||

| Voiced plosives | singleton | bᵊ | b' | bᵒ | b'ᵒ | dᵊ | d' | dᵒ | d'ᵒ | gᵊ | g' | gᵒ | g'ᵒ | ||||

| geminate | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Nasal | singleton | mᵊ | m' | mᵒ | m'ᵒ | nᵊ | n' | nᵒ | n'ᵒ | ||||||||

| geminate | mmᵊ | mm' | * | * | * | nn' | * | * | |||||||||

| Voiceless fricatives | singleton | * | f' | * | * | sᵊ | s' | sᵒ | s'ᵒ | * | š' | * | * | hᵊ | h' | hᵒ | h'ᵒ |

| geminate | * | * | * | * | ssᵊ | ss' | ssᵒ | ss'ᵒ | * | šš' | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Voiced fricatives | singleton | vᵊ | v' | vᵒ | v'ᵒ | zᵊ | z' | zᵒ | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| geminate | vvᵊ | vv' | * | * | * | zz' | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Affricate | singleton | čᵊ | * | * | |||||||||||||

| geminate | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximants | singleton | lᵊ | l' | lᵒ | l'ᵒ | ||||||||||||

| geminate | llᵊ | ll' | llᵒ | ll'ᵒ | |||||||||||||

| Central approximants | singleton | rᵊ | r' | rᵒ | r'ᵒ | jᵊ | * | jᵒ | j'ᵒ | ||||||||

| geminate | rrᵊ | rr' | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

The symbol "*" in the two tables above means that these consonant sounds are possible in Siberian Ingrian Finnish, but the words containing these sounds have not yet been found in the audio data.[45]

Examples of words with these additional consonant sounds are shown below. Sound p': ennemp' - earlier, vanemp' - eldest. Sound pp': krampp' - hook(hanger).GEN. Sound pᵒ: ampᵒ - shoot.IPF.3SG. Sound ppᵒ: piippᵒ - tube, kirppᵒ - flea. Sound tᵊ: pöütᵊ (weak aspiration) - table, luutᵊ (weak aspiration) - broom. Sound t': praht' - garbage, laht' - open (adverb), leht' - leaf, sheet, unoht' - forget.IPF.3SG. Sound tᵒ: rohtᵒ - medicine, maitᵒ - milk, lintᵒ - bird, tultᵒ - come.PRC_PSS, tahtᵒ - want.IPF.3SG, pantᵒ - put.PRC_PSS. Sound t'ᵒ: näht'ᵒ - to see.PRC_PSS.SG, pest'ᵒ - wash.PRC_PSS.SG. Sound zz': grizz' - gnaw.IPF.3SG. Sound š': tovariš' - comrade. Sound ss'ᵒ: püss'ᵒ - gun (rifle). Sound kk': säkk' - bag (sack), tükk' - field. Sound r' or r'ᵒ: höür' (höür'ᵒ) - steam (vapor). Sound rrᵊ: kuərrᵊ - sour cream.

Grammar

Personal Pronouns

The personal pronouns of Siberian Ingrian Finnish are shown in the table:[47]

| Case / Person | 1SG | 2SG | 3SG | 1PL | 2PL | 3PL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | miə | siə | hä / hän | müə | tüə | hüə |

| Genetive | miun | siun | hänen | mejjen | tejjen | hejjen |

| Accusative | mejjet | tejjet | hejjet | |||

| Partitive | minnu / mint | sinnu / sint | hänt | meit | teit | heit |

| Illative | minnu | sinnu | hänt | mejjes | tejjes | hejjes |

| Inessive | mius | sius | hänes | mejjes | tejjes | hejjes |

| Elative | miust | siust | hänest | mejjest | tejjest | hejjest |

| Adessive - Allative | miul | siul | häl / hänel | meil' | teil' | heil' / hejjel' |

| Ablative | miult | siult | hält / hänelt | mejjel't | tejjel't | hejjel't |

| Translative | miuks | siuks | häneks | mejjeks | tejjeks | hejjeks |

| Comitative | miunka | siunka | hänenkä | mejjenkä | tejjenka | hejjenka |

Personal pronouns are the only part of speech for which there is an accusative case (plural only).

Numerals

The names of cardinal numbers 1 to 10:[48] üks, kaks, kolt, neli, viis, kuus, seitsen, kaheksan, üheksän, kümmen.

The names of cardinal numbers 11 to 19:[48] ükstojst, kakstojst, kolttojst, nelitojst, viistojst, kuustojst, seitsentojst, kaheksantojst, üheksäntojst.

The names of cardinal numbers twenty, thirty etc.[48]: number from the first ten + ten.PRT (kümmen-t). For example, thirty - koltkümment, forty two - nelikümment kaks.

The ordinal numbers:[49] 1st - ensimäjn, 2nd - toin, 3rd - kolmas, 4th - nell'äs, 5th vijjes, 6th - kuvves.

Nouns

Nouns in Siberian Ingrian Finnish are inflected by 10 cases and 2 numbers (singular and plural).[50][51] There are 5 stems for the formation of nouns:

- Main stem (a word in the nominative case, singular);

- Partitive stem singular PRT.SG (for the formation of a word in the partitive case, singular);

- Illative stem singular ILL.SG (for the formation of a word in the illative case, singular);

- Oblique stem singular OBL.SG (for the formation of words in all oblique cases and for the formation of a word in the nominative case, plural);

- Oblique stem plural OBL.PL (for the formation of words in all cases, in plural, except the formation of words in the nominative case, plural).

All possible stems,[50] all possible suffixes[51] and an example of the declension paradigm of the word kukk[52] "flower" are shown in the table below:

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem | Suffix | Example | Stem | Suffix | Example | |

| Nominative | Main stem | ∅ | kukk | OBL.SG stem | -t | kuka-t |

| Genetive | OBL.SG stem | -n | kuka-n | OBL.PL stem | -n | kukki-n |

| Partitive | PRT.SG stem | pure PRT.SG stem, -t, -tt | kukka | OBL.PL stem | -j, -t | kukki-j |

| Illative | ILL.SG stem | pure ILL.SG stem, -s, -h | kukka | OBL.PL stem | -s | kukki-s |

| Inessive | OBL.SG stem | -s | kuka-s | OBL.PL stem | -s | kukki-s |

| Elative | OBL.SG stem | -st | kuka-st | OBL.PL stem | -st | kukki-st |

| Adessive - Allative | OBL.SG stem | -l, OBL.SG-n pääl | kuka-l, kuka-n pääl | OBL.PL stem | -l | kukki-l |

| Ablative | OBL.SG stem | -lt, OBL.SG-n päält | kuka-lt, kuka-n päält | OBL.PL stem | -lt | kukki-lt |

| Translative | OBL.SG stem | -ks | kuka-ks | OBL.PL stem | -ks | kukki-ks |

| Comitative | OBL.SG stem | -n'ka, -n'kä | kuka-n'ka | OBL.PL stem | -n'ka, -n'kä | kukki-n'ka |

The declension paradigm of the word kukk also includes the words: piippᵒ "tube", huntt' "wolf", rankk "heavy", penkk' "bench", harakk "magpie", kant "trunk" and etc.[52] Siberian Ingrian Finnish has at least 16 declension paradigms for nouns.[53]

Verbs

Verbs in Siberian Ingrian Finnish have finite and non-finite forms. Verbs in finite form have the following grammatical categories: mood, tense, person, number, and polarity item. Non-finite verb forms: infinitive, supine, impersonal verbs, and participle.[54][55]

The example of a verb paradigm is shown in the table:[56]

| Haasta To Speak |

Stem | Suffix |

|---|---|---|

| INF | haasta- | ∅ |

| SUP | haast- | -mä |

| IPS.PST | haasse- | -(t)ti |

| NEG; IMP.2SG | haass- | ∅; ∅ |

| IMP.2PL | haasta- | -ke |

| 1SG.PRS; 1PL.PRS; 2SG.PRS; 2PL.PRS | haassa- | -n; -m; -t; -t |

| 1SG.PST; 1PL.PST; 2SG.PST; 2PL.PST | haasso- | -n; -m; -t; -t |

| 3SG.PRS; 3PL.PRS | haasta- | ∅; -t |

| 3SG.PST | haastᵒ- | ∅ |

| 3PL.PST | haasto- | -vät |

| PRS_PSS | haasse- | -ttᵒ |

| PRS_ACT.SG | haasta- | -(n)t |

| PRS_ACT.PL | haastə- | -(n)et |

Samples

In the video, an example of speech in Siberian Ingrian Finnish, a woman says that her mother had an old lutheran liturgical book (she called it "Jumalan kiriə") in Finnish. The book had a sheet with an alphabet and a picture. The picture was a girl, a dog, and a story. The story was that there was no food and the dog found a piece of bread and gave it to the girl, and that the dog's name was Veikᵒ.

All examples are shown below from Sidorkevich 2014.[2]

Tükk'

field.NOM.SG

jäi

leave.PST.NPFV.3SG

küntä-mä-tt.

plow.DEST.ABS

Field left unplowed.

Uks

door.NOM.SG

nois'

begin.PST.NPFV.3SG

tule-ma

come.DEST

laht'.

openly

The door began to open.

Tüttᵒ

girl.NOM.SG

ono

be.PRS.3SG

kultsi-n

golden.PL-GEN

tilduko-nka.

earring.PL-COM

The girl has gold earrings.

Tämä-s

This.INS

külä-s

village.INS

ono

be.PRS.3SG

pall'ᵒ

many

ihməsti-j.

person.PL-PRT

There are many people in this village.

Tütse-t

girl.NOM.PL

kene-st

who.ELA

siə

2SG

haassa-t,

tell.2SG

hüə

3PL

ellä-t

live.3PL

naapri-n

neighbor.GEN

tuva-s.

house.INS

The girls you're talking about live neighbor house.

Poikse-t

boy.NOM.PL

kel'

who.ADE

ol-ti

be.IMP.PST

sukulajse-t

relativ.NOM.PL

linna-s

city.INS

män-ti

go.IMP.PST

linna.

city.ILL

Boys who had relatives in the city went to the city.

Kui

if

siə

2SG

ol-isi-t

be.COND.2SG

hän-t

3SG.PRT

teh-t'ᵒ

do.PP

vihase-ks

angry.TRANSL

hä

3SG

ol-is

be.COND.3SG

siu-n

2SG.GEN

pääl

at

kill'u-ma.

yell.DEST

If you made him angry, he would yell at you.

References

- Ubaleht, Ivan; Raudalainen, Taisto-Kalevi (May 2022). Development of the Siberian Ingrian Finnish Speech Corpus. Fifth Workshop on the Use of Computational Methods in the Study of Endangered Languages at 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2022), Dublin, Ireland. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.computel-1.1.

- Sidorkevich (Сидоркевич), Daria (Дарья) (2014). Язык ингерманландских переселенцев в Сибири: структура, диалектные особенности, контактные явления. Дисс. канд. филол. наук (PhD thesis) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: The Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Sidorkevich, Daria (2011). "On domains of adessive-allative in Siberian Ingrian Finnish". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. 7 (3): 575–607 – via CyberLeninka.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 23.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 24.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 24–25.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 25.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 17.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 35–36.

- "Suomalainen seurakunta Rjuskowassa Siperian maalla". Maamiehen Ystävä. 28: 1–3. 1844.

- "A small note about the fire in Ryzhkovo on April 25, 1846". Maamiehen Ystävä. 36: 3. 1846.

- Castrén, Matthias Alexander (1870). "Några upplysningar om de till Sibirien deporterade Finnarne". Nordiska resor och forskningar VI. Tillfälliga uppsatser. Helsingfors.: 138–144.

- Granö, Johannes (1893). Kuusi vuotta Siperiassa. Helsinki: Weil & Göös.

- Granö, Johannes Gabriel (1905). Siperian suomalaiset siirtolat. Helsinki (Kuopio): K. Malmströmin kirjapaino.

- Granö, Paavo (1914). "Siperian suomalaiset". Kansanvalistusseuran Kalenteri 1915. Helsinki: Kansanvalistusseura.: 27–46.

- Granö, Paavo (1926). Kannisto, A.; Setälä, E.N.; Sirelius, U.T.; Wichman, Y. (eds.). "Siperian suomalaiset". Suomen Suku. Helsinki: Otava.: 288–293.

- Juntunen, Alpo (1982). "Länsi-Siperian inkeriläiset siirtolat". Turun Historiallinen Arkisto. 38: 350–367.

- Juntunen, Alpo (1983). Suomalaisten karkottaminen Siperiaan autonomian aikana ja karkotetut Siperiassa. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriön vankeinhoito-osasto.

- Saari, Juha (1994). Valoa Siperiaan. Kirkollinen työ Siperian suomalaisten parissa 1863–1921. Yleisen kirkkohistorian pääainetutkielma. Abstract. Helsinki: Helsingin Yliopisto.

- Engman, Max (2005). Suureen itään: suomalaiset Venäjällä ja Aasiassa. Turku: Siirtolaisuusinstitutti.

- Sidorkevich 2012, p. 198.

- Sidorkevich 2012, pp. 198–199.

- Zlobina (Злобина), Vieno (Виено) (1971). "Кто такие корлаки?" [Who are Korlaks?]. Советское финно-угроведение (in Russian). 2: 87–91.

- Zlobina, Vieno (1972). "Mitä alkujuurta Siperian suomalaiset ja korlakat ovat". Kotiseutu (in Finnish). 2 (3): 86–92.

- Nirvi, Ruben (1972). "Siperian inkeriläisten murteesta ja alkuperästä". Kotiseutu (in Finnish). 2 (3): 92–95.

- Viikberg (Вийкберг), Juri (Юри) (1989). Эстонские языковые островки в Сибири (возникновение, изменения, контакты). Дисс. канд. филол. наук (PhD thesis). Tallinn: The Institute of Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR.

- Viikberg, Juri (2002). Wei, Li; Dewaele, Jean-Marc; Housen, Alex (eds.). "Language shift among Siberian Estonians: Pro and contra". Opportunities and Challenges of Bilingualism. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. 87: 125–144. doi:10.1515/9783110852004.125. ISBN 9783110852004.

- Korb, Anu (1998). Seitse küla Siberis. (Eesti asundused III) (in Estonian). Tartu: Eesti kirjandusmuuseum.

- Korb, Anu (2003). "Virulased, a multiethnic and multicultural communitiy in Ryzhkovo village, West-Siberia". Pro Ethnologia. 15: 29–47.

- Korb, Anu (2007). Rõžkovo virulased pärimuskultuuri kandjaina (in Estonian). Tartu: Eesti kirjandusmuuseum.

- Jürgenson, Aivar (1998). Tuisk, Astrid (ed.). "Emakeele osast Siberi eestalste etnilises identiteedis". Eesti kultuur võõrsil: Loode-Venemaa ja Siberi asundused (in Estonian). Tartu: Eesti kirjandusmuuseum: 126–140.

- Jürgenson, Aivar (2002). Siberi eestlaste territoriaalus ja identiteet (in Estonian). Tallinn: Tallinna Pedagoogikaülikooli kirjastus.

- Jürgenson, Aivar (2004). "On the formation of the Estonians' concepts of homeland and home place". Pro Ethnologia. 18: 97–114.

- Jürgenson, Aivar (2006). Siberiga seotud: eestlased teisel pool Uuraleid (in Estonian). Tallinn: Argo.

- Sidorkevich (Сидоркевич), Daria (Дарья) (2012). "Ингерманландцы в Сибири: этническая идентичность в многоэтничном окружении". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana (in Russian). 8 (1): 194–285 – via CyberLeninka.

- Kuznetsova, Natalia (January 2016). "Evolution of the Non-Initial Vocalic Length Contrast across the Finnic Varieties of Ingria and Adjacent Areas" (PDF). Linguistica Uralica. Tallinn: Estonian Academy Publishers publishes. 52 (1): 1–25. doi:10.3176/lu.2016.1.01.

- Kuznetsova, Natalia (May 2019). "Phonetic Realisation and Phonemic Categorisation of the Final Reduced Corner Vowels in the Finnic Languages of Ingria". Phonetica. De Gruyter Mouton. 76 (2–3): 201–233. doi:10.1159/000494927. PMID 31112960. S2CID 162170200 – via ResearchGate.

- "Glottolog". Glottolog. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- Sidorkevich 2012, p. 200.

- Sidorkevich 2012, p. 263, 274.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 64.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 66–68.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 69.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 76–77.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 85–87.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 88.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 183–184.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 193.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 194.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 156.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 157.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 169.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 170–171.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 195.

- Sidorkevich 2014, p. 198.

- Sidorkevich 2014, pp. 340–341.

Sources

- Sidorkevich, Daria (2012). "Ингерманландцы в Сибири: этническая идентичность в многоэтничном окружении". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana (in Russian). 8 (1): 194–285 – via CyberLeninka.

- Sidorkevich, Daria (2014). Язык ингерманландских переселенцев в Сибири: структура, диалектные особенности, контактные явления. Дисс. канд. филол. наук (PhD thesis) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: The Institute for Linguistic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

External links

- Working Repository of Siberian Ingrian Finnish contains audio, video and annotations under a free license (CC BY)

- Siberian Ingrian Finnish Talking Dictionary