Siege of Paris (1870–1871)

The siege of Paris took place from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871 and ended in the capture of the city by forces of the various states of the North German Confederation, led by the Kingdom of Prussia. The siege was the culmination of the Franco-Prussian War, which saw the Second French Empire attempt to reassert its dominance over continental Europe by declaring war on the North German Confederation. The Prussian-dominated North German Confederation had recently emerged victorious in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which led to the questioning of France's status as the dominant power of continental Europe. With a declaration of war by the French parliament on 16 July 1870, Imperial France soon faced a series of defeats at German hands over the following months, leading to the Battle of Sedan, which, on 2 September 1870, saw a decisive defeat of French forces and the capture of the French emperor, Napoleon III.

| Siege of Paris | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Prussian War | |||||||

_-_Paris%252C_1871_-_St_Cloud%252C_La_place.jpg.webp) Saint-Cloud after French and German bombardment during the battle of Châtillon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 240,000 regulars |

200,000 regulars, Garde Mobile and sailors 200,000 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 16,000 dead or wounded |

24,000 dead or wounded 249,142 capitulated[1] 47,000 civilian casualties | ||||||

With the capture of Napoleon III, the government of the Second French Empire collapsed and the Third French Republic was declared, provisionally led by the Government of National Defense. Despite German forces reaching and besieging Paris by 19 September 1870, the new French government advocated for the continuation of the war, leading to over four more months of fighting, during which Paris was continuously besieged. With the city fully encircled, the Parisian garrison attempted three unsuccessful break-out attempts and German forces began a relatively ineffectual artillery bombardment campaign of the city in January 1871. In response to the poor results of the artillery bombardment, the Prussians brought forth large-caliber Krupp heavy siege artillery to attack the city beginning 25 January 1871. With the renewed artillery attack and an increasingly starving and ill Parisian population and garrison, the Government of National Defense would conclude armistice negotiations with the North German Confederation on 28 January 1871. While the armistice led to food shipments being immediately permitted into the city, the capture of their capital city and the disaster of the war itself would have a long-lasting impact on the French populace, Franco-German relations, and Europe as a whole. French defeat in the war would directly lead to a victorious North German Confederation unifying with still-independent South German states and declaring the German Empire[2] as well as a disgruntled and radicalized Parisian population taking control of Paris and forming the Paris Commune.[3]

Background

As early as August 1870, the Prussian 3rd Army led by Crown Prince Frederick of Prussia (the future Emperor Frederick III), had been marching towards Paris.[4] A French force accompanied by Napoleon III was deployed to aid the army encircled by Prussians at the Siege of Metz. This force were crushed at the Battle of Sedan, and the road to Paris was left open. Personally leading the Prussian forces, King William I of Prussia, along with his chief of staff Helmuth von Moltke, took the 3rd Army and the new Prussian Army of the Meuse under Albert, Crown Prince of Saxony, and marched on Paris virtually unopposed. In Paris, the Governor and commander-in-chief of the city's defenses, General Louis Jules Trochu, assembled a force of 60,000 regular soldiers who had managed to escape from Sedan under Joseph Vinoy or who were gathered from depot troops. Together with 90,000 Mobiles (Territorials), a brigade of 13,000 naval seamen and 350,000 National Guards, the potential defenders of Paris totaled around 513,000.[5] The compulsorily enrolled National Guards were, however, untrained. They had 2,150 cannon plus 350 in reserve, and 8,000,000 kg of gunpowder. [6]

The French had expected the war to be fought mainly on German soil; it was not until the defeats at Spicheren and Frœschwiller that the authorities began to take serious action in organizing the defenses of Paris.[7] A committee under the leadership of Marshall Vaillant was formed and given a budget of 12 million francs to strengthen the defenses. Barriers were put up around the city, 12,000 workers employed to dig earthworks, a barrage placed across the Seine, and select approaches to the city laid with electrically-triggered mines. Forests and houses were cleared to improve the firing sight lines, roads were torn up, and railroad and road entrances to the city blocked. The Paris Catacombs were sealed off, along with certain quarries and excavations outside the city to deny an entry-point to the Prussians.[8][9]

The authorities in Paris also attended to provisions and took steps to stockpile cereals, salted meat, and preserves for the population. Much of this was stored in the Opéra Garnier. The Bois de Boulogne and Luxembourg Gardens were packed with livestock – the former received some 250,000 sheep and 40,000 oxen.[10][11] The government believed it had enough flour and wheat to last for 80 days, more than enough based on the assumption, then prevalent, that the siege would be relatively brief.[12]

Siege

.jpg.webp)

The Prussian armies quickly reached Paris, and on 15 September Moltke issued orders for the investment of the city. Crown Prince Albert's army closed in on Paris from the north unopposed, while Crown Prince Frederick moved in from the south. On 17 September a force under Vinoy attacked Frederick's army near Villeneuve-Saint-Georges in an effort to save a supply depot there, but it was eventually driven back by artillery fire. [13] The railroad to Orléans was cut, and on the 18th Versailles was taken, and then served as the 3rd Army's and eventually Wilhelm's headquarters. By 19 September the encirclement was complete, and the siege officially began. Responsible for the direction of the siege was General (later Field Marshal) von Blumenthal. [14]

Prussia's chancellor Otto von Bismarck suggested shelling Paris to ensure the city's quick surrender and render all French efforts to free the city pointless, but the German high command, headed by the king of Prussia, turned down the proposal on the insistence of General von Blumenthal, on the grounds that a bombardment would affect civilians, violate the rules of engagement, and turn the opinion of third parties against the Germans, without speeding up the final victory.

It was also contended that a quick French surrender would leave the new French armies undefeated and allow France to renew the war shortly after. The new French armies would have to be annihilated first, and Paris would have to be starved into surrender.

Trochu had little faith in the ability of the National Guards, which made up half the force defending the city. So instead of making any significant attempt to prevent the investment by the Germans, Trochu hoped that Moltke would attempt to take the city by storm, and the French could then rely on the city's defenses. These consisted of the 33 km (21 mi) Thiers wall and a ring of sixteen detached forts, all of which had been built in the 1840s.[15] Moltke never had any intention of attacking the city and this became clear shortly after the siege began. Trochu changed his plan and allowed Vinoy to make a demonstration against the Prussians west of the Seine. On 30 September Vinoy attacked Chevilly with 20,000 soldiers and was soundly repulsed by the 3rd Army. Then on 13 October the II Bavarian Corps was driven from Châtillon but the French were forced to retire in face of Prussian artillery.

General Carey de Bellemare commanded the strongest fortress north of Paris at Saint Denis. [16]

On 29 October de Bellemare attacked the Prussian Guard at Le Bourget without orders, and took the town. [17] The Guard actually had little interest in recapturing their positions at Le Bourget, but Crown Prince Albert ordered the city retaken anyway. In the battle of Le Bourget the Prussian Guards succeeded in retaking the city and captured 1,200 French soldiers. Upon hearing of the French surrender at Metz and the defeat at Le Bourget, morale in Paris began to sink. The people of Paris were beginning to suffer from the effects of the German blockade. On 31 October, the day the government confirmed the surrender of Metz and one day after Le Bourget's recapture was announced, an angry mob besieged and invaded the Hôtel de Ville, taking Trochu and his cabinet hostage.[18] The insurgent leaders (Gustave Flourens, Louis Charles Delescluze, Louis Auguste Blanqui among them) attempted to depose Trochu's government and form a new one led by themselves, but they could not come to an agreement.[19] In the meantime, battalions of loyal National Guards led by Jules Ferry and a detachment of Mobiles headed by the Prefect of Police, Edmond Adam, prepared to retake the building. Negotiations between the two sides concluded with a peaceful evacuation of the building by the insurgents early in the morning of November 1, and the release of the hostages.[20] Despite promising no reprisals against the revolutionaries, the Government was swift to arrest and imprison 22 of the leaders, which further embittered the left-wing of Paris.[21]

Hoping to boost morale on 30 November Trochu launched the largest attack from Paris even though he had little hope of achieving a breakthrough. Nevertheless, he sent Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot with 80,000 soldiers against the Prussians at Champigny, Créteil and Villiers. In what became known as the battle of Villiers the French succeeded in capturing and holding a position at Créteil and Champigny. By 2 December the Württemberg Corps had driven Ducrot back into the defenses and the battle was over by 3 December.

On 21 December, French forces attempted another breakout at Le Bourget, in the hopes of meeting up with General Faidherbe's army. Trochu and Ducrot had been encouraged by Faidherbe's capture on 9 December of Ham, around 65 miles from Paris.[22] The weather was extremely cold, and the well-installed, well-concealed Prussian artillery inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing French. Soldiers camped overnight with no fuel for warmth, as the temperature fell to 7°F (−14°C). There were over 900 cases of frostbite, and 2,000 casualties on the French side. On the Prussian side, there were less than 500 dead.[23]

On 19 January a final breakout attempt was aimed at the Château of Buzenval in Rueil-Malmaison near the Prussian Headquarters, west of Paris. The Crown Prince easily repulsed the attack inflicting over 4,000 casualties while suffering just over 600. Trochu resigned as governor and left General Joseph Vinoy with 146,000 defenders.

During the winter, tensions began to arise in the Prussian high command. Field-Marshal Helmuth von Moltke and General Leonhard, Count von Blumenthal, who commanded the siege, were primarily concerned with a methodical siege that would destroy the detached forts around the city and slowly strangle the defending forces with a minimum of German casualties.

But as time wore on, there was growing concern that a prolonged war was placing too much strain on the German economy and that an extended siege would convince the French Government of National Defense that Prussia could still be beaten. A prolonged campaign would also allow France time to reconstitute a new army and convince neutral powers to enter the war against Prussia. To Bismarck, Paris was the key to breaking the power of the intransigent republican leaders of France, ending the war in a timely manner, and securing peace terms favourable to Prussia. Moltke was also worried that insufficient winter supplies were reaching the German armies investing the city, as diseases such as tuberculosis were breaking out amongst the besieging soldiers. In addition, the siege operations competed with the demands of the ongoing Loire Campaign against the remaining French field armies.

Air medical transport is often stated to have first occurred in 1870 during the siege of Paris when 160 wounded French soldiers were evacuated from the city by hot-air balloon, but this myth has been definitively disproven by full review of the crew and passenger records of each balloon which left Paris during the siege.[24]

During the siege, the only head of diplomatic mission from a major power who remained in Paris was United States Minister to France, Elihu B. Washburne. As a representative of a neutral country, Washburne was able to play a unique role in the conflict, becoming one of the few channels of communication into and out of the city for much of the siege. He also led the way in providing humanitarian relief to foreign nationals, including ethnic Germans.[25]

Food & fuel shortages

As the siege wore on, food supplies dwindled, and prices skyrocketed. The authorities instituted price controls on certain staple foods at the beginning of the siege, but these were rendered ineffective by a lack of enforcement and the rampant black market in the city.[26] Until mid-October there was no rationing of any kind, and afterwards only meat was subject to rationing (bread was rationed at the very end of the siege). There were also no attempts to limit hoarding and speculation. Many of the wealthier residents were well-placed to weather the siege since they had put aside stores of food before it began.[27] Infant mortality soared because of the lack of fresh milk. Poor women and their children suffered the most of anybody. Their husbands had the relative advantage of their 1.50 francs per day National Guard pay, "little enough of which reached their wives", and the fact that they were occupied, because "anyone who was occupied – even the National Guardsman warming himself in the bistro while his wife queued for food – had a better chance of survival."[28]

Parisians turned first to horses in early-October to supplement their dwindling supplies of fresh meat. By mid-November, fresh meat had truly run out in the city, and butchers began offering dog and cat meat. People also turned to rats for meat, although the numbers of rats consumed was relatively low due to fear of disease, and the expense of preparing rat meat in order to make it edible.[29] Once the supply of those animals ran low, the citizens of Paris turned on the zoo animals residing at Jardin des plantes. Even Castor and Pollux, the only pair of elephants in Paris, were slaughtered for their meat. [30]

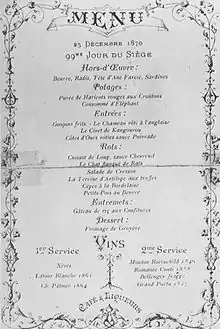

A Latin Quarter menu contemporary with the siege reads in part:

- * Consommé de cheval au millet. (horse)

- * Brochettes de foie de chien à la maître d'hôtel. (dog)

- * Emincé de rable de chat. Sauce mayonnaise. (cat)

- * Epaules et filets de chien braisés. Sauce aux tomates. (dog)

- * Civet de chat aux champignons. (cat)

- * Côtelettes de chien aux petits pois. (dog)

- * Salamis de rats. Sauce Robert. (rats)

- * Gigots de chien flanqués de ratons. Sauce poivrade. (dog, rats)

- * Begonias au jus. (flowers)

- * Plum-pudding au rhum et à la Moelle de Cheval. (horse)

The increasing hunger of the Parisians coincided with bitterly cold winter weather and a dire lack of fuel for heat. Coal gas, because of its essential use for the balloons, was strictly rationed and mostly replaced by oil. On November 25, oil itself was requisitioned.[31] This left people reliant on increasingly scarce supplies of wood. By late-December, the inhabitants of working-class Belleville were so desperate for wood they had felled the street trees of their neighborhoods and were moving into the wealthier areas of western Paris, cutting down trees along the Champs Élysées and Avenue Foch.[32] By January, 3,000–4,000 people were dying per week from the effects of cold and hunger.[33] There were sharp rises in cases of smallpox, typhoid, and especially pneumonia. Typhoid came because the siege forced Parisians to turn to the Seine for much of their drinking water.[34]

Bombardment

In January, on Bismarck's advice, the Germans fired some 12,000 shells into the city over 23 nights in an attempt to break Parisian morale. [35] The attack on the city itself was preceded by the bombardment of the southern forts from the Châtillon Heights on 5 January. That day, the guns of forts Issy and Vanves were silenced by a relentless barrage, allowing the Prussian artillery to be moved up to 750 yards closer to Paris. This made a crucial difference, as from their previous position the guns were only capable of reaching the fringes of the city. The first shells fell on the Left Bank that same day.[36]

Prussian artillerymen aimed their guns at the highest angles possible and increased the charges to obtain unprecedented ranges. Even so, although shells reached the Pont Notre-Dame and the Île Saint-Louis, none made it to the Right Bank.[37][38] Up to 20,000 refugees fled the Left Bank, putting a further strain on the already overburdened food supplies of the Right Bank arrondissements.[39] The domes of the Panthéon and the Invalides were frequent targets of the artillerymen, and the vicinities of those buildings were particularly damaged as a result. Shells also struck the Salpetrière Hospital and the Théâtre de l'Odéon (then being used as a hospital), leading some to believe that the Prussians were deliberately targeting hospitals. Moltke, in response to a complaint on this matter from Trochu, responded that he hoped to soon move the artillery closer so that his gunners could better identify the Red Cross flags.[40][41]

About 400 perished or were wounded by the bombardment which, "had little effect on the spirit of resistance in Paris."[42] Delescluze declared, "The Frenchmen of 1870 are the sons of those Gauls for whom battles were holidays." In actuality, the level of destruction fell short of what the Prussians had expected. The shells often caused little damage to the buildings they struck, and many fell in open spaces away from people.[43] An English observer, Edwin Child, wrote that he "Became more and more convinced of the impossibility of effectually bombarding Paris, the houses being built of such solid blocks of stone that they could only be destroyed piecemeal. One bomb simply displaces one stone, in spite of their enormous weight..."[44]

Armistice and surrender

On 25 January 1871, Wilhelm I overruled Moltke and ordered the field-marshal to consult with Bismarck for all future operations. Bismarck immediately ordered the city to be bombarded with large-caliber Krupp siege guns. This prompted the city's surrender on 28 January 1871.

Secret armistice discussions began on January 23, 1871 and continued at Versailles between Jules Favre and Bismarck until the 27th. On the French side there was concern that the National Guard would rebel when news of the capitulation became public. Bismarck's advice was to "provoke an uprising, then, while you still have an army with which to suppress it". The final terms agreed on were that the French regular troops (less one division) would be disarmed, Paris would pay an indemnity of two hundred million francs, and the fortifications around the perimeter of the city would be surrendered. In return the armistice was extended until February 19.[45]

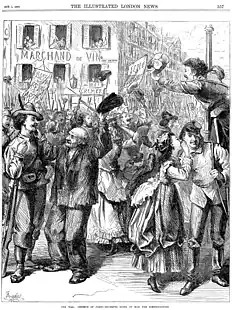

Food supplies from the provinces, as well as shiploads from Britain and the United States, began to enter the starving city almost immediately.[46] Britain sent ships from the Royal Navy loaded with Army food provisions, while private organizations like the Lord Mayor's Relief Fund and the London Relief Committee made significant donations. According to the British representative responsible for distributing the foodstuffs, at the beginning of February the London Relief Committee donated "nearly 10,000 tons of flour, 450 tons of rice, 900 tons of biscuits, 360 tons of fish, and nearly 4,000 tons of fuel, with about 7,000 head of livestock".[47] The United States sent around $2 million worth of food, but much of it was held up at the port of Le Havre because of a shortage of workers for unloading the ships. The arrival of the first British convoy of food at Les Halles sparked a riot and pillaging, "while for seven hours the police seemed powerless to intervene".[48]

Thirty thousand Prussian, Bavarian and Saxon troops held a brief victory parade in Paris on March 1, 1871 and Bismarck honored the armistice by sending trainloads of food into the city. The German troops departed after two days to take up temporary encampments to the east of the city, to be withdrawn from there when France paid the agreed war indemnity. While Parisians scrubbed the streets "polluted" by the triumphal entry, no serious incidents occurred during the short and symbolic occupation of the city. This was in part because the Germans had avoided areas such as Belleville, where hostility was reportedly high.[49]

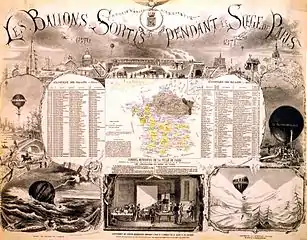

Air mail

Balloon mail was the only means by which communications from the besieged city could reach the rest of France. The use of balloons to carry mail was first proposed by the photographer and balloonist Felix Nadar, who had established the grandiosely titled No. 1 Compagnie des Aérostatiers, with a single balloon, the Neptune, at its disposal, to perform tethered ascents for observation purposes. However the Prussian encirclement of the city made this pointless, and on 17 September Nadar wrote to the Council for the Defence of Paris proposing the use of balloons for communication with the outside world: a similar proposal had also been made by the balloonist Eugène Godard.

The first balloon launch was carried out on 23 September, using the Neptune, and carried 125 kg (276 lb) of mail in addition to the pilot. After a three-hour flight it landed at Craconville 83 km (52 mi) from Paris.[50] Following this success a regular mail service was established, with a rate of 20 centimes per letter. Two workshops to manufacture balloons were set up, one under the direction of Nadar in the Elysée-Montmartre dance-hall (later moved to the Gare du Nord),[51] and the other under the direction of Godard in the Gare d'Orleans. Around 66 balloon flights were made, including one that accidentally set a world distance record by ending up in Norway.[52] The vast majority of these succeeded: only five were captured by the Prussians, and three went missing, presumably coming down in the Atlantic or Irish Sea. The number of letters carried has been estimated at around 2.5 million.[53]

Some balloons also carried passengers in addition to the cargo of mail, most notably Léon Gambetta, the minister for War in the new government, who was flown out of Paris on 7 October. The balloons also carried homing pigeons out of Paris to be used for pigeon post. This was the only means by which communications from the rest of France could reach the besieged city. A specially laid telegraph cable on the bed of the Seine had been discovered and cut by the Prussians on 27 September,[54] couriers attempting to make their way through the German lines were almost all intercepted, and although other methods were tried, including attempts to use balloons, dogs, and message canisters floated down the Seine, these were all unsuccessful. The pigeons were taken to their base, first at Tours and later at Poitiers, and when they had been fed and rested were ready for the return journey. Tours lies some 200 km (120 mi) from Paris and Poitiers some 300 km (190 mi) distant. Before release, they were loaded with their dispatches. Initially the pigeon post was only used for official communications but on 4 November the government announced that members of the public could send messages, these being limited to twenty words at a charge of 50 centimes per word.[55]

These were then copied onto sheets of cardboard and photographed by a M. Barreswille, a photographer based in Tours. Each sheet contained 150 messages and was reproduced as a print about 40 by 55 mm (1.6 by 2.2 in) in size: each pigeon could carry nine of these. The photographic process was further refined by René Dagron to allow more to be carried: Dagron, with his equipment, was flown out of Paris on 12 November in the aptly named Niépce, narrowly escaping capture by the Prussians. The photographic process allowed multiple copies of the messages to be sent, so that although only 57 of the 360 pigeons released reached Paris more than 60,000 of the 95,000 messages sent were delivered.[56][57] (some sources give a considerably higher figure of around 150,000 official and 1 million private communications,[58] but this figure is arrived at by counting all copies of each message.)

Aftermath

.jpg.webp)

Late in the siege, Wilhelm I was proclaimed German Emperor on 18 January 1871 at the Palace of Versailles. The kingdoms of Bavaria, Württemberg, and Saxony, the states of Baden and Hesse, and the free cities of Hamburg and Bremen were unified with the North German Confederation to create the German Empire. The preliminary peace treaty was signed at Versailles, and the final peace treaty, the Treaty of Frankfurt, was signed on 10 May 1871. Otto von Bismarck was able to secure Alsace-Lorraine as part of the German Empire.

The continued presence of German troops outside the city angered Parisians. Further resentment arose against the French government, and in March 1871 Parisian workers and members of the National Guard rebelled and established the Paris Commune, a radical socialist government, which lasted through late May of that year.

In popular culture

Empires of Sand by David W. Ball (Bantam Dell, 1999) is a novel in two parts, the first of which is set during the Franco-Prussian war, more particularly the Siege of Paris during the winter of 1870–71. Key elements of the siege, including the hot-air balloons used for reconnaissance and messages, the tunnels beneath the city, the starvation and the cold, combine to render a vivid impression of war-time Paris before its surrender.

The Old Wives' Tale by Arnold Bennett is a novel which follows the fortunes of two sisters, Constance and Sophia Baines. The latter runs away to make a disastrous marriage in France, where after being abandoned by her husband, she lives through the Siege of Paris and the Commune.

The King in Yellow, a short story collection by Robert W. Chambers, published in 1895, includes a story titled "The Street of the First Shell" which takes place over a few days of the siege.[59]

References

- German General Staff 1884, p. 247.

- "Siege of Paris | Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Nelsson, compiled by Richard (2019-06-26). "The Paris Commune – from the archive, 1871". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Moltke 1892, p. 166.

- Horne 2002, p. 62.

- Ollier 1873, p. 495.

- Howard, 2001; p. 319

- Horne, 1965; pp. 63–64

- Howard, 2001; p. 319

- Horne, 1965; p. 65

- Gérard Cagna (2012-03-10). "Le siège de Paris de l'hiver 1870/1871" (in French). L'Obs.

- Horne, 1965; pp. 65–66

- Moltke 1892, pp. 116–119.

- Howard 1961, p. 352.

- Howard 1961, p. 318.

- Ollier 1873, pp. 334–338.

- Howard 1961, p. 334.

- Horne, 1965; pp. 107–113

- Horne, 1965; pp. 110–111

- Horne, 1965; pp. 115–118

- Horne, 1965; pp. 118–119

- Horne, 1965; p. 190

- Horne, 1965; pp. 191–193

- Lam 1988, pp. 988–991.

- McCullough 2011.

- Horne, 1965; p. 181

- Horne, 1965; p. 181

- Horne, 1965; pp. 185, 221

- Horne, 1965; pp. 177–179

- Howard 1961, p. 327.

- Horne, 1965; 219–220

- Horne, 1965; 219–220

- Wawro 2003; p. 282

- Horne, 1965; p. 221

- Howard 1961, pp. 357–370.

- Horne, 1965; pp. 203–204, 212

- Horne, 1965; p. 213

- Howard, 1961; p. 361

- Horne, 1965; pp. 212–213

- Horne, 1965; pp. 213–214

- Howard, 1961; p. 362

- Cobban 1961, p. 204.

- Howard, 1961; p. 361

- Horne, 1965; pp. 216–217

- Horne 2002, p. 240.

- Horne 2002, p. 248.

- Horne, 1965; p. 248

- Horne, 1965; pp. 248–249

- Horne 2002, p. 263.

- Holmes 2013, p. 268.

- Fisher 1965, p. 45.

- "No. 1132: The Siege of Paris". www.uh.edu. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Holmes 2013, pp. 292–193.

- Fisher 1965, p. 22.

- Fisher 1965, p. 70.

- Holmes 2013, p. 286.

- Lawrence, Ashley. "A Message brought to Paris by Pigeon Post in 1870–71". Microscopy UK. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Levi 1977.

- "The Project Gutenberg eBook of The King in Yellow, by Robert W. Chambers". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

Books

- Cobban, Alfred (1961). A History of Modern France: From the First Empire to the Fourth Republic 1799–1945. Pelican Book. Vol. II. London: Penguin. OCLC 38210316.

- Fisher, John (1965). Airlift 1870: The Balloon and Pigeon Post in the Siege of Paris. London: Parrish. OCLC 730010076.

- German General Staff (1884). The Franco-German War 1870–71: Part 2; Volume 3. Translated by Clarke, F.C.H. London: Clowes & Sons.

- Holmes, Richard (2013). Falling Upwards. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-738692-5.

- Horne, Alistair (2002) [1965]. The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870–71 (repr. Pan ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-49036-8.

- Howard, Michael (1961). The Franco–Prussian War. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26671-0.

- Levi, Wendell (1977). The Pigeon. Sumter, SC: Levi. ISBN 978-0-85390-013-9.

- McCullough, D. (2011). The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-7176-6.

- Moltke, Field Marshal Count Helmuth von (1892). The Franco-German War of 1870. Vol. I. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Ollier, E (1873). Cassells History of the War between France and Germany 1870–1871. Vol. I. London, Paris, New York: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin.

Journals

- Lam, D. M. (October 1988). "To Pop A Balloon: Air Evacuation During The Siege of Paris, 1870". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. Alexandria, VA: Aerospace Medical Association. 59 (10): 988–991. ISSN 0095-6562.

Further reading

- Chandler, David G. (1980). Atlas of Military Strategy. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-905750-6.

- Richardson, Joanna. "The Siege of Paris, 1870-71" History Today (Sep 1969), Vol. 19 Issue 9, pp 593–599

External links

- The French Army 1600–1900

- Map of European situation at the time of the Siege of Paris (omniatlas.com)

- The Siege and Commune of Paris, 1870–1871: Photographs in the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Website of the Bry-sur-Marne's Museum – Collections of the Museum Adrien Mentienne, related to the major events that occurred in Bry-sur-Marne, including the Battle of Villiers in 1870, during the Siege of Paris (English version available)