Siege of Jülich (1621–1622)

The siege of Jülich was a major operation in the second phase of the Eighty Years' War that took place from 5 September 1621 to 3 February 1622. A few months after the Twelve Years' Truce between the Dutch Republic and the Spanish Monarchy expired, the Spanish Army of Flanders, led by the Genoese nobleman Ambrogio Spinola, went on the offensive against the Republic and approached the Rhine river to mask its true intentions: laying siege to the town of Jülich, which the Dutch States Army had occupied in 1610 during the War of the Jülich Succession. Although the capture of the town would not allow for a Spanish invasion of the Republic, its location between the Rhine and Meuse rivers rendered it strategically significant for both sides, given that the United Provinces greatly benefited from the river trade with the neighboring neutral states and Spain was pursuing a strategy of blockading the waterways which flowed across the Republic to ruin its economy.

| Siege of Jülich | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

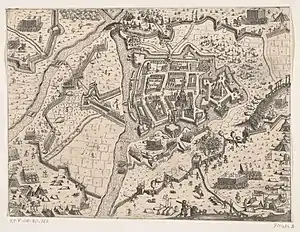

The Siege of Jülich (ca. 1622), anonymous engraving. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Frederik Pithan Maurice of Orange |

Ambrogio Spinola Hendrik van den Bergh | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,500[1]-3,000[2] | 12,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The siege operations were undertaken by a relatively small force under Count Hendrik van den Bergh, a Catholic cousin of Prince Maurice of Orange, while the Spanish main army under Spinola took positions along the neighboring Duchy of Cleves to prevent the States Army under Maurice to relieve Jülich. Located far away from the Dutch border, the town had strong defenses and was well garrisoned by a force under Frederik Pithan. Spinola therefore ordered a blockade to starve the defenders while they were submitted to regular bombardments. Pithan launched several sorties over the siege works, but they achieved little. An attempt by Maurice to sneak some troops across the Spanish lines also failed. In January 1622, the defenders, decimated by hunger and cold, surrendered to Van den Bergh.

During 1622 and 1623, the Spanish Army completely evicted the Dutch troops from the rest of the Duchy of Jülich, as well as from the towns and castles that they held in Westphalia. Though the river blockade was ultimately unsuccessful, Jülich remained in Spanish control until 1660, and the Catholic victory was celebrated by artworks commissioned by the Spanish Crown and the Spinola family. Additionally, it was reported while it was ongoing by the fledgling press of the Northern and Southern Netherlands.

Background

After the conclusion of the three-year long Siege of Ostend in 1604, the Spanish Army of Flanders under Ambrogio Spinola, who had assumed command one year before, went on the offensive against the United Provinces for the first time since 1599. The character of the war between the Spanish Monarchy and the Dutch Republic had changed greatly since the 1590s, given that the Dutch had turned their towns along the Meuse, Waal, Linge and Lek rivers into artillery fortresses, thereby creating four solid lines of defense in their southern border.[4] Spinola therefore avoided the so-called 'river barriers' and directed his campaign beyond the Rhine and the IJssel rivers, where he took the towns of Lingen and Oldenzaal in the Achterhoek and Twente in 1605, and Groenlo in 1606, besides Wachtendonk and Rheinberg on the Lower Rhine, which enabled the Spanish Army to quickly link with its new conquests. To protect the Republic from the threat, the Dutch stadtholder and commander of the States' Army, Maurice of Nassau, had to build a chain of wooden forts connected by earth ramparts on the west bank of the IJssel from the Zuiderzee to Arnhem, on the Nederrijn from there to its confluence with the Waal at Schenkenschans, then to Tiel along the north bank of the Waal.[4] Besides, the Republic was forced to post strong garrisons at the towns and forts along the IJssel, and consequently, to increase the size of the army, yet by 1607 the field forces available to Maurice were meagre.[5] The finances on both sides were strained, so on 9 April 1609, following months of negotiations, Spain and the Republic signed a twelve-years truce.[6]

.png.webp)

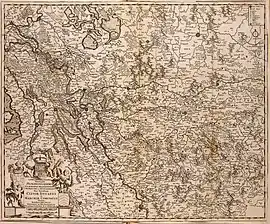

While the demobilitzation was ongoing, a succession crisis broke in the states of the late Duke Johann Wilhelm of Jülich, which, besides that duchy, included those of Cleves and Berg, the counties of Mark and Ravensberg, and the Lordship of Ravenstein. These territories were located on both sides of the Rhine in the vicinity of the Northern and Southern Netherlands, and therefore both Spain and the Republic considered to intervene in the crisis.[7] Those who had the strongest claim to the succession were John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, and Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg. They agreed in July 1609 to rule the territories together. However, since they were both Lutherans and Johann Wilhelm had been Catholic, the Imperial authorities claimed that the compromise breached the Augsburg Interim, and an army under Archduke Leopold V of Tirol, bishop of Strasbourg and Passau, was sent to occupy Jülich.[8] While Spain refused to intervene as it was dealing with the Expulsion of the Moriscos, the Dutch Republic and France did it and dispatched troops to join the armies of Brandenburg and the Palatinate-Neuburg to besiege Jülich. The Imperial garrison surrendered after a month of fight on 2 September 1610. Maurice, who had led the operations, installed a strong garrison in the town.[9]

Situation remained quite for four years. In 1614, however, the Count Palatine of Neuburg converted to Catholicism and drove the Brandenburger troops of Düsseldorf. This time, the Spanish Army intervened on his side. Spinola moved out from Maastrich in late August and, in a swift campaign, occupied the rebellious Free Imperial City of Aachen, supported by Brandenburg, 10 towns and villages in Cleves, including Wesel, 28 in Jülich, and 24 in Berg and Mark.[10] The Dutch reacted by garrisoning 70 infantry companies in other towns and villages in Jülich, Cleves and Mark –including Emmerich and Rees– in order to cut the Spanish lines of communications between the Rhineland and the towns seized in 1605–1606 in the Achterhoek and Twente.[11] Open was averted through negotiation, but the situation remained tense, especially as both sides bolstered their position by seizing new towns. In 1616, Spinola occupied Soest, while in 1620, Maurice, who had sized power in the Republic after toppling the pro-peace Grand Pensionary Oldenbarnevelt in 1618, sent troops up the Rhine to seize and fortify an island on the confluence of the said river and the Sieg.[12] The new fort was known as Papenbril or Pfaffenmütze (Monk's Spectaces or Monk's Cowl) and allowed the Dutch to intercept the traffic on the Rhine between Cologne and Bonn.[13]

%252C_RP-P-OB-80.971.jpg.webp)

By late 1620, as the end of the Twelve Years' Truce came close, voices in Spain and the Dutch Republic diverged on the convenience of renewing it or resume the war. The debate was particularly intense in the Spanish Court.[14] Since Spain was already heavily involved in the Thirty Years' War, on January Archduke Albert persuaded Philip III about the need of renewing the truce, and was authorized to open talks with Maurice.[15] This were conducted through Bartholda van Swieten, a relative of the Count of Tilly, commanding general of the Army of the Catholic League, who lived at The Hague and was close to Maurice.[16] Aiming at drawing the reluctant Dutch provinces on his side by evidencing the threat of a Spanish invasion, Nassau engaged in a double game and offered the archdukes to use his authority to reintegrate the Republic into the Spanish Monarchy, and therefore a Southern delegation headed by Petrus Peckius the Younger, chancellor of Brabant, was dispatched to The Hague. He addressed the States General on 23 March and, after referring to the Low Countries as a common fatherland, he stated that the archdukes did not wish to pursue war against their rebellious subjects without first admonishing them to return to obedience. According to Peckius proposition, the United Provinces would have to recognize the archdukes as their sovereigns, as well as granting the Catholics freedom of worship and lifting their blockade on the Scheldt river. In exchange, Philip III would allow them to keep their self-government and open the Indies to the Dutch trade.[17] The proposition was utterly rejected, and Maurice succeeded in building a common front in favour of the war. The prospect of renewing the war was popular in Holland and, specially, in Zeeland, since it would allow their elite to benefit from trade with the Indies and privateering on the high seas.[18] The fear to a Spanish military offensive, moreover, drew the inland provinces, till then reluctant to carry the burden of the military operations, in favour of not renewing the truce.[17]

Preparations and strategy

The death of Philip III on 31 March altered the situation in Spain, since his son and successor, the then 16-years old Philip IV, favored the pro-war faction in the Spanish power spheres, headed by Baltasar de Zúñiga –already in control of the Spanish foreign policy since 1618– and his nephew and close associate Gaspar de Guzmán, Count of Olivares.[15] The strategy to follow in case of a continuation of the conflict had been discussed at Madrid and Brussels since 1618. Cristóbal Benavente, veedor general of the Army of Flanders, argued for the conquest of Cleves and a limited thrust in the Arnhem region, combined with embargoes in Spain and its Italian viceroyalties, and a river blockade in the Netherlands and north-west Germany.[18] In March 1621, Maestre de Campo Carlos Coloma, whom Spinola had sent to the Spanish court, made a similar proposal, arguing for 'put the war on them on the Betuwe by crossing the Waal, or in the Veluwe by going over the IJssel'.[19] He also pointed out to the need of taking Jülich and Pfaffenmütze, since 'I do not know how it would be possible to enter it [Holland] leaving them in our back'.[20] The Brussels court was convinced that the Dutch too would make the first moves in the Rhineland and, once the truce expired on 9 April, Albert advised the Elector of Cologne to mobilize 2,000 infantry and 300 cavalry to protect its states. Albert also feared Dutch offensives over Münster, Paderborn and, notably, Liège, where Maurice had inherited the enclave of Herstal –just 5 km from Liège– from his elder brother Philip William.[12] To strengthen the army, recruits were carried out at the Low Countries, Germany and the Franche-Comté. Additionally, an effort was made to complete the ranks of the Spanish tercios.[21]

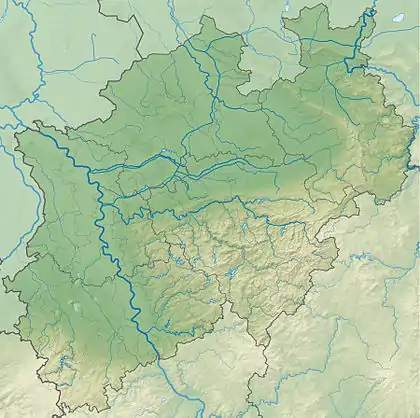

While Spain opted for an offensive stance, the States' preparations for the war were mostly defensive. As the end of the truce approached, officers had been ordered to return to their regiments before the end of March, and, from 3 to 8 February, the State Council had met with Prince Maurice to discuss the strategy.[22] It was resolved to bolster the defenses of the towns and forts in the Zeelandic Flanders, including those of Sluis, Aardenburg, Oostburg and IJzendijke, as well as those of Bergen op Zoom and Steenbergen, in the northern Brabant, and those of the borders of Guelders and Overijssel, including the strategic fortress of Coevorden.[22] Additionally, they decided to increase the size of the Dutch and German companies up to 150 soldiers, and the Walloon, English and French ones up to 120. On 10 February, the prince and the State councillors decided to increase the fortifications of Emmerich, Rees and Jülich, and also to send supplies to Pfaffenmütze.[22] Since the Spanish were in control of Groenlo, Oldenzaal and Lingen, plus several forts nearby, Maurice believed that, like in 1606, the Spanish offensive would come over the IJssel line.[23] On 1 July, the States directed 20,000 florins to build redoubts along the Waal and the IJssel. Meanwhile, to prevent the Spanish from levying war contributions on the Veluwe and the area around Nijmegen, Maurice gave orders to cut all the trees along the left bank of the IJssel and to dismantle the bridges over the Berkel, an affluent of the IJssel, up to Keppel and Doetinchem.[24]

Campaign

Open war resumed on 3 August, just three weeks after Archduke Albert had died. 400 Dutch cavalry soldiers from the garrisons of Breda and Bergen op Zoom raided the outskirts of Antwerp and returned with some booty and prisoners.[25] In the meantime, both armies were gathered, the Dutch at Schenkenschans and the Spanish at Maastricht. Spinola assembled a force of 15,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.[26] The horse was led by captain-general don Luis de Velasco and lieutenant-general Count Hendrik van den Bergh. The infantry consisted of the Spanish tercios of Simon Antúnez, Diego Mejía and Diego Luis de Oliveira, the Irish tercio of the Count of Tyrone, the Italian tercios of Marcelo Judice and Lelio Brancaccio, and the Walloon tercios of the Lord of Bournonville and the Baron of Valançon.[27] Another, smaller army under Íñigo de Borja was left to defend Flanders, and the garrisons of Brabant, specially those of Lier and 's-Hertogenbosch, were bolstered. The Brussels' Council of State had resolved that Jülich should be taken. Instead of advancing directly to the town, however, Spinola aimed at confounding his enemy over his true intentinos and led his army across the Roer over a pontoon bridge and then encamped his army at Büderich, on the west bank of the Rhine, opposite to Wesel. In response, Maurice advanced to Emmerich and entrenched his army between the said town and Rees.[25]

Heavy rains poured over the region during September. The States' Army camp was flooded with water up to mid-leg, which forced Maurice to bring more than 30,000 wooden plates to be laid over the wet groud, while the forage for the horses became extremely scarce. At first it was tried to lodge the horses at stables in Emmerich and Rees, but the price was too high, so Maurice had to send the cavalry back to Anrhem, Zutphen and Doesburg.[28] Spinola's army, encamped on a higher ground, was far less affected by the rains. With Jülich far beyond his lines, the Spanish commander determined to occupy a string of towns in Cleves to prevent the Dutch from relieving it. He first dispatched Van den Bergh with 14 cavalry companies to take Gennep, located at the confluence of the Niers with the Meuse. Gennep belonged to the neutral County of Moers, but had a small Dutch garrison. Van den Bergh menaced to raze the surroundings if they did not surrender, which, pressed by the town's governor, they ultimately did.[29] Meanwhile, Luis de Velasco, in command of 4,000 men and four cannon, took Sonsbeck, Goch, Kalkar and several minor towns.[30]

With Cleves secured, Spinola ordered Van den Bergh to invest Jülich with 6,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry and 8 cannons. He was instructed to capture on his way the castle of Rheydt, a well fortified place garrisoned by 150 Dutch soldiers under Captain Reinhard Tytfort, from Livonia.[31] The castle belonged to Floris van Boetzelaer, Lord of Odenkirchen, who had allowed it to be garrisoned by Dutch troops on condition that the commander should follow his orders. Van den Bergh send cavalry troops to control the roads nearby and detain anyobody that left Rheydt. Van Boetzelaer and his lawyer Brouwers, from Cologne, were captured and taken to Van den Bergh, who pressed the lord to oblige Tytfort to surrender.[30] The lawyer ask to be released because of this status as a subject of a neutral prince, but he ended up being sent back to the castle with a written order for Tytfort to surrender, which he did on 30 August.[32] The Dutch garrison was allowed to leave the castle with their weapons and baggage. Van den Bergh offered Tytfort a place in the Spanish Army, but he refused. He was court-martialed on his arrival to the State's Army camp and sentenced to the capital punishment. The sentence was carried out on 14 September. His immediate subordinates, Lieutenant Kemp-ten-Ham and Ensign George Stuyrer, were expelled from the Army.[33]

Siege

.jpg.webp)

The Spanish Army approached Juliers on 4 September. That day, the Spanish troops seized over 500 cows, oxen, horses and sheep belonging to the inhabitants of Jülich, which were grazing outside the town and which Van den Bergh ordered to be brought to the castle of Breitenbend, near Linnich. On the other hand, he forbade his men to take cattle from the population of the villages nearby.[34] The Spanish also took the ripe wheat of the crop fields around the city. The governor of Jülich, Frederick Pithan, had been pressed by most of the officers under his command to order the wheat to be collected and stored inside the city, but he refused, as the orders he had from the Council of State insisted on imposing as few exactions as possible upon the locals. On 5 July, the Spanish army began to invest Jülich and diverted the course of the Roer, which dried up the moats of the city walls. Next day, 4,000 men taken from the garrisons of Artois and Hainaut arrived from Maastricht and joined the siege. Meanwhile, Spinola, with the bulk of the army, left its camp at Büderich and moved to Gladbach.[35]

Jülich was a small, albeit well-fortified town. Its defenses dated back from the mid-16th century and had been designed by the architect Alessandro Pasqualini, from Bologna. A large citadel with four bastions dominated the town from its northern side. It housed the ducal residence, designed as a palazzo in fortezza. The town's walls had the shape of an elongated pentagon with two of the five corners covered by the citadel and the other three defended by four bastions. These, like the ramparts, were made of earth with a thick brick cover. When completed in 1580, the fortress was considered one of the strongest in Europe, yet the Dutch, after its capture in 1610, deemed it vulnerable and bolstered it with a number of hornworks and ravelins in front of the bastions and the ramparts of the citadel.[36] The States' garrison had originally numbered 4,000 men and it was one of the largest of the Dutch Republic for prestige reasons, but on the expiration of the truce it had been reduced to 2,500 to 3,000 men –22 companies in all–, as Maurice had called 1,000 men to join the field army.[37] Its commander was the 72 years old Frederik Pithan, sergeant-major general and lieutenant-colonel of the Regiment of Count Ernst Casimir of Nassau-Dietz. The fortress was in a good state of defense and supplied with everything except money to pay the troops, so that it was difficult for Pithan to maintain discipline.[38]

%252C_RP-P-OB-80.979.jpg.webp)

Since the defenses of Jülich were strong and its garrison large, Spinola decided to take it by hunger instead of by assault. He ordered Van den Bergh to build a line of circumvallation reinforced with forts and redoubts around the town to further isolate it.[1] The Count established the bulk of his troops north of Jülich, in front of the citadel, in the area spanning from Stetternich to Broich, with his quarter at Mersch.[39] Instead of remaining inactive, Pithan ordered several sorties upon the Spanish positions. The first one, just as the blockade had begun, was directed to the town's mills, which were burnt to prevent its use by the Spanish troops. In mid-September, 700 infantry and all the cavalry of the garrison attacked by surprise Van den Bergh's encampment. 54 Spanish soldiers died during the fight, as opposite to 16 foot and 8 horse Dutch soldiers.[39] On 26 September, 200 musketeers and 100 cavalrymen fell upon a redoubt of the circumvallation line, but they were promptly rebuffed with the loss of 50 men by its defenders with the help of Van den Bergh himself, who rushed the post in command of 100 cavalry soldiers.[40]

While the blockade was ongoing, the States' Army levied war contributions in Berg, Recklinghausen, Münster and Paderborn to sustain itself. Because of the continuous rains, the soldiers guarding the convoys walked knee-deep in mud. Moreover, the Rhine and other rivers began to overflow, further hindering the supply of the States' Army. As the cold arrived in October, men and horses began to fall ill, and many soldiers defected to the Spanish.[38] At the same time, Maurice ordered two forts to be built, one of five large bastions opposite to Rees and another one with four small bastions in front of Emmerich.[1] Since the Spanish were in control of Wesel, Geldern and Venlo, plus advanced positions in Cleves, Maurice deemed a direct attempt at relieving Jülich too risky. He therefore conceived a plan in late November to sneak a number of infantry aboard 40 boats up the Meuse to land in the vicinity of Gennep, where they would be joined by 15 cavalry companies, and then take by surprise the small town of Maaseik, in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, to open a way to Jülich. Spinola, however, was informed about the plan through a letter from Cologne. He instructed the garrison of Maaseik to stay in alert and deployed the bulk of the army around Dülken, between Maaseik and Juliers, to intercept the relief force. When the Dutch troops found that the Spanish had anticipated them, they immediately withdrew.[41]

Once the new forts were completed, Maurice ordered the fortifications of Cleves and Kranenburg to be dismantled. On 3 December, the States' Army left Emmerich and its regiments were sent back to their garrisons to rest during the winter.[38] The Spanish army, on the other hand, remained around Jülich in spite of the cold. In order to prompt Pithan to surrender, Spinola subjected the town to a heavy bombardment day and night. Food became so scarce inside Jülich that the garrison was put under a strict rationing. Horse meat was reserved for the officers, while the rank and file had to content themselves with dog, cat and rat meat. Firewood was also very scarce, and the soldiers suffered from a bitter cold.[42] On 17 January, Pithan opened negotiations for the surrender and sent to the Spanish camp a commission of three captains, one of each nationality of the States' troops in the garrison, namely German, French and English. The terms were agreed on 20 January and signed two days later by Pithan and Van den Bergh. A truce would ensue until 3 February, and that day the garrison would surrender if it had not been relieved. Spinola would respect the Protestant cult in Jülich, allow the officials of the Elector of Brandenburg to stay at the town, let the garrison to leave with its weapons, flags and baggage, and escort it to Nijmegen. Pithan agreed to hand over all the ammunitions and supplies to the Spanish, as well as the official papers and letters belonging to the Duchy of Juliers.[43]

During the truce, soldiers from the besieging army met with troops from the Dutch garrison and shared their impressions. The defenders deplored having to surrender to a small army, while the besiegers attributed this to the lack of cavalry that they experienced. On 3 February, the States' surviving garrison, numbering 2,000 men, abandoned Jülich across the citadel's bridge. The infantry marched ahead, followed by the baggage wagons, which carried also 40 ill soldiers. Pithan, on horseback, closed the column with the 70 remaining cavalry soldiers, under Captain Thomas Villers.[44] The Dutch troops marched with the flags folded and their muskets unloaded and with their matches off.[45] Before leaving, Pithan was given the keys of the city by the burgomasters. He then delivered them, along with those of the citadel, to Count Van den Bergh, who immediately took control of the town.[44] There, the Spanish troops took 36 cannons and 200 tons of powder and ammunitions.[45]

Aftermath

Having secured Jülich, Van den Bergh sent detachments to occupy the rest of the duchy. Then, while Spinola re-crossed the Meuse with his troops back to the Brabant, the Count garrisoned his army in the duchy for the duration of the winter. Cardinal de la Cueva reported Philip IV from Brussels that 'the Dutch greatly regret the loss of Jülich'.[2] Though the capture of the town did not open a way for the Spanish Army to invade the Republic, it allowed their troops to be fed at the expense of a neutral territory. Moreover, the Republic had spent large sums of money over the previous twelve years to keep and strengthen Jülich's defenses.[46] In line with her instructions to appoint Spaniards rather than Netherlanders as military governors of towns conquered from the Dutch, the Infanta Isabella named Don Diego de Salcedo, a veteran officer, as governor of Jülich. Soon after his arrival to Nijmegen, Pithan was summoned to The Hague and court-martialed for the loss of the fortress. Unlike the ill-fated Tytfort, he was, nevertheless, honourably acquitted, owing to his reputation as a fine soldiers, chiefly because of his actions at the Battle of Nieuwpoort, where he had been severely wounded.[46]

In the summer of 1622, Spinola launched an offensive against the Republic and laid siege to Bergen op Zoom. The control of the Rhine was, nevertheless, vital to interrupt the trade between the United Provincies and the German States. Therefore, a substantial force under Van den Bergh was sent to besiege Pfaffenmütze. On 27 December, after five months of bombardment, the Dutch garrison, reduced to 300 able men from an original force of 700, surrendered the fortress.[2] The Elector of Cologne asked the Infanta for the fort to be demolished, but Spinola advised Isabella to keep it. Despite the complaints, a German garrison in Spanish service was installed at Pfaffenmütze. The locals welcomed the change, since, unlike the previous Dutch occupants, the Spanish did not levied war contributions in the vicinity.[47] In the next few years, following instructions from Madrid, the Spanish Army increased its pressure on the Lower Rhine and Westphalia to damage the Dutch economy. This greatly depended on the export of foodstuffs, materials and manufactures along the inland waterways to the Spanish Netherlands, Liège and Cologne.[48]

After the Army of the Catholic League under Tilly destroyed the Protestant forces of Christian of Brunswick on 6 August 1623 at Stadtlohn, the Spanish Army, acting of behalf of the Count Palatine of Neuburg, made rapid advances in Mark. By December 1623, it had taken the towns of Hamm, Unna, Kamen and Lippstadt from the Dutch and Brandeburger troops. Later it overran the County of Ravensberg, where they took the Dutch-held Sparrenberg Castle, and advanced as far as the Weser River.[47] With the Meuse, the Rhine and the Ems already in Spanish control, a full blockade was imposed in 1625, leading to the collapse of the Dutch trade. The price of products like cheese, butter, wine, herrings, spices, sugar, cloth and bricks experienced a sharp fall in the Republic, while to stop of the imports of Flemish flax and German timber caused a rise of 30% in the cost of shipbuilding timber in Holland.[49] On the other hand, the blockade led to difficulties in the supplying of the Spanish garrisons in the Low Countries and Germany and disrupted the Flemish commerce and much of Antwerp's insurance business in the Republic. Therefore, it was lifted in April 1629.[50] Dutch offensives while Spain was busy in the War of the Mantuan Succession, coupled with the Swedish advance in Germany over 1631 and 1632, led Philip IV and Olivares to hand over the majority of the Spanish-held fortresses in Germany to the Army of the Catholic League. Jülich, however, was kept until 1660, and the Spanish power remained strong in the Rhenish ecclesiastical states until the 1650s.[51]

Legacy

As the first major triumph of Spain in the Netherlands following the Twelve Years' Truce, the Siege of Jülich was depicted in a painting commissioned by the Spanish Crown to Jusepe Leonardo in 1634 to decorate the Salón de Reinos in the Buen Retiro Palace.[52] Ambrogio Spinola is shown in the foreground, accompanied by the Diego Felipez de Guzmán, 1st Marquess of Leganés, while he receives the keys of Jülich from the commander of the Dutch garrison. The town and a further landscape appear in the background, with the surrendered garrison leaving the citadel in front of the Spanish troops.[52] The dried moats are absent, as well as other details such as the burned mills or the snow that covered the landscape.[53] Count Hendrik van den Bergh was not included, since in 1632 he turned against Spain and fled to Liège, from where he tried to spark a revolt in the Southern Netherlands. As a traitor, his place next to Spinola in Leonardo's canvas was taken by Leganés, cousin of the Count-Duke of Olivares and son-in-law to Spinola, who participated in the campaign as a Maestre de Campo.[54] When the painting was commissioned, Spinola had died four years earlier, and Leganés was fighting in Germany, so Leonardo resorted to portraits by Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck to depict Spinola, and to an engraving by Paulus Pontius based on a drawing by Van Dyck to portray Leganés.[55] The painting has been compared to The Surrender of Breda by Diego Velázquez, noting the opposite attitude of the victor –Spinola, in both cases– towards the vanquished.[55]

.jpg.webp)

The siege is also the subject of another canvas by the Flemish battle painter Sebastian Vrancx, noted for this realistic depictions of war. The canvas, painted around 1635, shows a general view of the siege during the winter from the west, with the landscape covered in snow and the Roer river frozen. A series of Spanish redoubts and cottages appear on the foreground. Jülich is accurately depicted, with the town on the right with the round towers of the Hexenturm gate and the spire of the Mariä Himmelfahrt church, and the citadel with the palazzo in fortezza in the left. Further beyond, there is the Spanish main encampent at the village of Broich. A cavalry skirmish is seen in front of the citadel, near the Cologne road.[56] Pieter Snayers, pupil to Vrancx, painted a similar canvas from them same perspective, but with a higher viewpoint.[56] This paintings were commissioned by the Marquis of Leganés, a noted art collector who not only ordered paintings about the campaigns where he had taken part in a leading role, but also portraits of men who served under him, including the veteran sapper corporal Antonio Servás, who was at his service while he was general of artillery during the Siege of Bergen op Zoom.[57]

%252C_BK-NM-605.jpg.webp)

In Genoa, the Spinola family, namely Giovanni Battista Spinola, who was married to Maria, one of Ambrogio's sisters, commissioned Giovanni Carlone and Andrea Ansaldo to paint a series of frescos portraying Ambrogio's victories in a gallery of the family's summer residence, Villa Spinola di San Pietro, including the surrender of Jülich, which features in one of the lesser compartments of the vault, the central space being devoted to the Siege of Ostend.[58] Another cycle of frescos depicting Spinola's successes in Flanders was later commissioned to Ansaldo to decorate a gallery in the Palazzo Doria Spinola. Giovanni Battista's son Gio Filippo Spinola, following his father's steps, commissioned the Flemish artist Mattheus Melijn in 1636 to produce five silver reliefs depicting his uncle's victories to decorate a wooden cabinet. The furtiture has been lost, but the five plates have been preserved, one of them depicting the surrender of Jülich.[59]

Besides its pictorical portrays, the Siege of Jülich was widely reported in the first newspaper of the Habsburg Netherlands, the Nieuwe Tijdinghen, edited by Abraham Verhoeven, who had published news prints since 1605, including many about Spinola's campaigns in the Netherlands and Germany.[60] Verhoeven was likely patronized by Spinola himself, who promoted his reputation through the publication of books emphasizing his abilities and achievements, like Delle guerre di Fiandra (1609) by his chief of staff Pompeo Giustiniano, or the Obsidio Bredana (1626) by his confessor, the Jesuit Herman Hugo.[61] The siege was reported from the Dutch side as well. Nicolas van Geelkercken, a journalist who followed the States' Army as it marched on campaign, produced detailed illustrated broadsheets about the siege, as he had done when Jülich had been besieged by the Dutch in 1610. Much like Verhoeven and Spinola, Van Geelkercken lauded Maurice of Nassau in his works.[62]

Notes

- Beausobre 1733, p. 4.

- Israel 1997, p. 36.

- Israel 1997, p. 35.

- Parker 2004, p. 11.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 197.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 198.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 200.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 201.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 203.

- Israel 1997, p. 33.

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 205.

- Duerloo 2016, p. 510.

- Duerloo 2016, p. 510-511.

- Esteban Estríngana 2020, p. 136-137.

- Duerloo 2016, p. 506.

- Duerloo 2016, p. 507.

- Duerloo 2016, p. 508.

- Israel 1990, p. 8.

- Rodríguez Villa 1904, p. 388.

- Rodríguez Villa 1904, p. 389.

- Priego Fernández del Campo 2002, p. 406.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 83.

- Le Clerc 1728, p. 75.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 129-130.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 129.

- Beausobre 1733, p. 2.

- Céspedes y Meneses 1634, p. 53.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 130.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 131.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 132.

- Le Clerc 1728, p. 76.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 133.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 134.

- Richer 1622, p. 793-794.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 134-135.

- Büren & Grellert 2016, p. 237-250.

- Richer 1622, p. 793.

- Ten Raa & Bas 1915, p. 86.

- Sallengre 1728, p. 135.

- Richer 1622, p. 796.

- Richer 1622, p. 796-797.

- Richer 1623, p. 228.

- Richer 1623, p. 230-231.

- Richer 1623, p. 233.

- Priego Fernández del Campo 2002, p. 411.

- Le Clerc 1728, p. 77.

- Israel 1997, p. 37.

- Israel 1990, p. 23.

- Israel 1990, p. 23-24.

- Israel 1990, p. 24.

- Israel 1997, p. 44.

- Torner Marco 2004, p. 35.

- Priego Fernández del Campo 1993, p. 413-414.

- Brown & Elliott 2005, p. 182.

- Úbeda de los Cobos 2005, p. 130-131.

- Martin 2022.

- Duvosquel 1985, p. 437.

- Colomer 2003, p. 159.

- Colomer 2003, p. 159-160.

- Arblaster 2014, p. 74.

- Arblaster 2014, p. 84-85.

- Helmers 2016, p. 356-359.

References

- Arblaster, Paul (2014). From Ghent to Aix: How They Brought the News in the Habsburg Netherlands, 1550-1700. Brill. ISBN 9789004276840.

- Beausobre, Isaac de (1733). Mémoires de Frederic Henri de Nassau Prince d'Orange (in French). Pierre Humbert.

- Brown, Jonathan; Elliott, John H. (2005). A Palace for a King: The Buen Retiro and the Court of Philip IV. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300101850.

- Büren, Guido von; Grellert, Marc (2016). "Architectura militaris im langen 17. Jahrundert amb Rhein. Die virtuelle Rekonstruktion der Bonner Heinrichbastion und ihr Kontext". In Rutz, Andreas; Tomczyk, Marlene (eds.). Krieg und Kriegserfahrung im Westen des Reiches 1568-1714 (in German). V&R unipress GmbH. pp. 237–272. ISBN 9783847103509.

- Céspedes y Meneses, Gonzalo de (1634). Historia de don Felipe IIII rey de las Españas (in Spanish). Sebastian de Cormellas.

- Colomer, José Luis (2003). "Ambrosio Spinola: fortuna iconográfica de un genovés al servicio de la Monarquía". In Boccardo, Piero; Colomer, José Luis; Di Fabio, Clario (eds.). España y Génova. Obras, artistas y coleccionistas (in Spanish). CEEH - Fundación Carolina. pp. 157–173. ISBN 978-84-949424-3-3.

- Duerloo, Luc (2016). Dynasty and Piety: Archduke Albert (1598-1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in an Age of Religious Wars. Routledge. ISBN 9781317147282.

- Duvosquel, Jean-Marie (1985). Splendeurs d'Espagne et les villes belges: 1500 - 1700 ; Bruxelles, Palais des Beaux-Arts, 25 sept. - 22 déc. 1985 (in French). Crédit communal.

- Esteban Estríngana, Alicia (2020). "Perderse en Flandes. Opciones y desafíos de la monarquía de Felipe IV en tres años decisivos (1621-1623)". In Fortea Pérez, José Ignacio; Gelabert González, Juan Eloy; López Vela, Roberto; Postigo Castellanos, Elena (eds.). Monarquías en conflicto. Linajes y noblezas en la articulación de la Monarquía Hispánica (in Spanish). Fundación Española de Historia Moderna - Universidad de Cantabria. pp. 131–194. ISBN 978-84-949424-3-3.

- Helmers, Helmer (2016). "Cartography, War Correspondence and News Publishing: The Early Career of Nicolaes van Geelkercken, 1610–1630". In Raymond, Joad; Moxham, Noah (eds.). News Networks in Early Modern Europe (in Spanish). Brill. pp. 350–374. ISBN 978-90-04-27717-5.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1990). Empires and Entrepots: Dutch, the Spanish Monarchy and the Jews, 1585-1713. Hambledon Press. ISBN 9780826431820.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1997). Conflicts of empires: Spain, the low countries and the struggle for world supremacy, 1585–1713. Hambledon Press. ISBN 9780826435538.

- Le Clerc, Jean (1728). Histoire des Provinces Unies des Pays-Bas (in French). Vol. II. Z. Chatelain.

- Richer, Estienne (1622). Le Mercure françois (in French). Vol. VII. Estienne Richer.

- Richer, Estienne (1623). Le Mercure françois (in French). Vol. VIII. Estienne Richer.

- Martin, Gregory (2022). "The Siege of Jülich, 1621-22". Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Nimwegen, Olaf van (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835752.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521543927.

- Priego Fernández del Campo, José (2002). La pintura de tema bélico del S. XVII en España (PhD). Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Rodríguez Villa, Antonio (1904). Ambrosio Spínola, primer marqués de los Balbases (in Spanish). Fortanet.

- Sallengre, Albert-Henri (1728). Essai d'une histoire des Provinces-Unies, pour l'année MDCXXI.: Où la trêve finit, & la guerre recommença avec l'Espagne (in French). Thomas Johnson.

- Ten Raa, F. J. G.; Bas, F. de (1915). Het Staatsche Leger van het sluiten van het Twaalfjarig Bestand tot den dood van Maurtis, prins van Oranje, graaf van Nassau (1609-1625) (in Dutch). Vol. III. Koninklijke Militaire Academie.

- Torner Marco, Ramón (2004). Jusepe Leonardo. Un pintor bilbilitano en la Corte de Felipe IV (in Spanish). Centro de Estudios Bilbilitanos. ISBN 84-7820-677-9.

- Úbeda de los Cobos, Andrés (2005). El palacio del Rey Planeta: Felipe IV y el Buen Retiro (in Spanish). Museo Nacional del Prado. ISBN 9788484800811.