Siege of Ngatapa

The siege of Ngatapa (Māori: Ngātapa) was an engagement that took place from 31 December 1868 to 5 January 1869 during Te Kooti's War in the East Coast region of New Zealand.

| Siege of Ngatapa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Te Kooti's War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| New Zealand government | Ringatū | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Colonel George Whitmore Ropata Wahawaha | Te Kooti | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Armed Constabulary Kūpapa (Ngāti Porou) | Ringatū | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 670 | 300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 11 killed |

at least 130 killed 150 prisoners, mostly women and children | ||||||

Te Kooti's War was part of the New Zealand Wars, a series of conflicts between the British, the local authorities and their Māori allies on one side, and several Māori iwi (tribes) on the other, that took place from 1843 to 1872. Like some of the later clashes in this period, Te Kooti's War had a religious basis. Te Kooti was the leader of the Ringatū religion and gathered a following of disenfranchised Māori who like himself had been exiled to the Chatham Islands in 1866 by the government. After two years of captivity, they escaped to the mainland, landing on the East Coast in July 1868. Pursued by the local militia, Te Kooti and his followers moved inland. He mounted a raid in November in Poverty Bay which resulted in the murders of several local settlers and a series of skirmishes with Māori aligned with the government—known as kūpapa—followed.

Te Kooti and his 300 followers, along with their families and a number of prisoners, retreated to the hillfort—or pā—at Ngatapa. An initial attack made on 4 December by warriors of the Ngāti Porou iwi, led by Ropata Wahawaha, was fended off. At the end of the month, the Armed Constabulary—a regular paramilitary force—commanded by Colonel George Whitmore, along with Ropata's Ngāti Porou warriors, surrounded the pā. After being encircled and cut off from their water supply for almost a week, Te Kooti and his men escaped down a cliff face that their attackers believed to be inaccessible. Many of Te Kooti's followers were subsequently captured and executed by the Ngāti Porou and some Māori members of the Armed Constabulary with the cognisance of Whitmore, a massacre that has in modern times been condemned as an abuse of law and human rights.

Background

From 1843 to 1872, there were a series of conflicts in New Zealand between some local Māori people on one side, and British imperial and colonial forces and their Māori allies on the other. These clashes are collectively termed the New Zealand Wars. While some of the wars of this period were as a result of land confiscations or clashes with the Māori King Movement, many of the later conflicts were due to the rise of prophetic Māori leaders and religious movements which threatened the autonomy of the government.[2] These movements also subverted tribalism so often were met with hostility by the leaders of many iwi (tribes) as well.[3] Te Kooti's War was the last of these later wars, and marked the final field engagements of the New Zealand Wars.[4]

The earliest conflicts of the New Zealand Wars saw Māori warriors using muskets in addition to their traditional weapons, such as striking staffs—or taiaha—and war clubs—or mere. By the time of Te Kooti's War, they were equipped with modern Snider–Enfield rifles; either captured in battle or purchased from arms dealers. They still retained their close combat weapons and were also known to use shotguns. Their opponents also used Snider-Enfield rifles but could rely on more reliable and robust supplies of ammunition compared to the Māori, who would have to rely on what they captured or scavenged.[5]

Te Kooti was a Māori warrior of the Rongowhakaata iwi who in 1865 had fought on the side of the New Zealand government against the Pai Mārire religious movement during the siege of Waerenga-a-Hika in Poverty Bay. Afterwards, already regarded as a troublemaker by the settlers in the region and some local Māori, he was arrested by the local magistrate and militia commander, Captain Reginald Biggs, on the grounds of being a spy; communications between Te Kooti and a Pai Mārire leader, supposedly arranging an ambush of local militia, had been intercepted. In March 1866 he was exiled without a trial to the Chatham Islands along with 200 Pai Mārire warriors and their families. While there he developed his own religion, Ringatū.[6][7][8] In 1868, he and his followers escaped from captivity and, now armed with weapons secured from the vessel they had commandeered to effect their escape, landed back at Poverty Bay in July.[9]

After rebuffing a request from Biggs to surrender, Te Kooti and his Ringatū warriors were pursued by the local militia, made up of European settlers, in order to prevent them moving inland.[10] A series of defeats followed for the militia as they endeavoured to stop Te Kooti's march to Puketapu, a hillfort—or pā—in the Urewera hill country. This resulted in Te Kooti acquiring more supplies for his men.[9] The militia were soon reinforced with troops from the Armed Constabulary, a paramilitary law enforcement agency that formed New Zealand's main defence force at the time and which was led by Colonel George Whitmore.[11][12]

In September, conflict in South Taranaki saw Whitmore and his men withdrawn to deal with that threat while the government sought a truce with Te Kooti, offering land in exchange for a surrender of arms. This did not meet with a response; Te Kooti did not trust the government.[13] Te Kooti then spread rumours that an attack on Wairoa in Hawke's Bay was imminent. However, on the night of 9/10 November, Te Kooti and his Ringatū men instead attacked a number of communities in Poverty Bay, including at Matawhero. There they massacred settlers, their families, and local Māori. Te Kooti sought revenge—or utu—for his banishment to the Chathams. Among those killed were Biggs, his wife, and their infant son. Soon afterwards, Te Kooti murdered a chief—or rangatira–Paratene Pototi, who had played a role in Te Kooti being sent to the Chathams. Six other rangatira were also executed.[14][15] Te Kooti remained in control of the area for a week, taking prisoners and gathering weapons and supplies.[16] As a result of the massacre, the government were now determined to deal with Te Kooti, placing a bounty for his capture and sending Whitmore's Armed Constabulary back to the region.[15]

Prelude

On 17 November, Te Kooti began withdrawing his forces and captives from Poverty Bay to the rural community of Makeretu, known now as Ashley Clinton, about 48 kilometres (30 mi) west of Tūranga—now Gisborne. Two days later, 200 Ngāti Kahungunu warriors—kūpapa or Māori who were aligned with the Government—arrived in the area to reinforce the 240 Māori warriors already present in the area, and together began their pursuit of Te Kooti. They attacked Makeretu and met the Ringatū forces in open battle. The kūpapa were forced into a defensive posture on a ridge about 1.6 kilometres (0.99 mi) from Makeretu, and one of the Ngāti Kahungunu leaders was among the 20 warriors killed. They held their positions while awaiting supplies of ammunition. However, Te Kooti sent a small raiding party to attack the depot that was the expected source of the supplies of ammunition and this proved successful. They routed the small garrison at the depot and plundered 16,000 rounds of ammunition for Te Kooti's forces.[17]

The kūpapa were still able to hold their defensive positions due to their greater numbers but needed reinforcements and ammunition before they could go on the offensive. A force of around 370 kūpapa, led by Ropata Wahawaha of the Ngāti Porou iwi, arrived at Makeretu on 2 December, bringing the total number opposing Te Kooti to over 800. Now resupplied with ammunition portered directly from Tūranga, they attacked Te Kooti's position the following day. However, Te Kooti had moved most of his fighters, along with women, children, food and livestock, to the pā of Ngatapa, about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) further inland. Only a small rearguard had been left at Makeretu, and at least 14 were killed and some others taken prisoner.[18]

Following the capture of Makeretu, Ropata's Ngāti Porou wanted to execute some of the prisoners, but Tareha Te Moananui, the leader of the Ngāti Kahungunu contingent, refused, and returned to Tūranga with most of his men. The inter-tribal dispute had delayed a move to Ngatapa by Ropata's forces, which now numbered around 450 kūpapa, by nearly a day.[18][19]

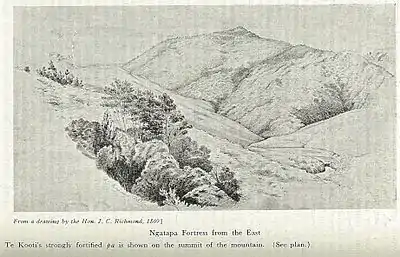

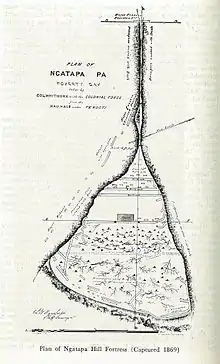

Ngatapa

Ngatapa, about 56 kilometres (35 mi) from Poverty Bay and 24 kilometres (15 mi) northwest from the modern township bearing its name, was a pā located on a hilltop rising 800 metres (2,600 ft) from a ridge. An elongated, narrow ridge extended away to the west side of the pā while its southern side was steep and covered in bush. The northern side was nearly sheer. A secondary hill, known as the Crow's Nest and about 800 metres (2,600 ft) to the east rose from the same ridge, and this formed the approach to the base of the hilltop, which was triangular in shape. Te Kooti had strengthened the defences of the pā with a series of three trenches, earth banks and palisades, as well as covered walkways connecting the trenches. The interior of the pā was a maze of rifle pits.[20][21]

Pā had been a key to success for Māori combatants in previous campaigns, as the British and colonial forces had discovered. When outnumbered, Māori often used a well-constructed pā to negate the advantage of the superior firepower possessed by the attacking Europeans and kūpapa.[22]

Belich argues that Ngatapa was more a traditional pā than a modern one. A fault with the fortifications at Ngatapa was that the parapets were excessively wide, creating a blind spot immediately in front them. When Te Kooti laid out the defensive arrangements he gave little consideration to the construction of traps and diversions, often problematic for attackers of modern pā. Another weakness was the lack of a water source within the pā which, after the withdrawal from Makaretu, would contain around 300 of Te Kooti's warriors, their families plus numerous prisoners, at least 500 people in all. A further problem was a lack of a clear line of retreat, a common feature for modern pā. Nonetheless, Ngatapa was considered a serious obstacle for attacking forces.[20][21]

Siege

On 4 December, after an initial attack on Ngatapa by the remaining kūpapa was beaten off by concentrated fire from the Ringatū, Ropata and a European officer, Lieutenant George Preece of the Armed Constabulary who was attached to the Ngāti Porou contingent, led a party up close to the pā and during the course of the afternoon small groups of warriors were able to join them. Eventually, they breached the outer defensive trench. As night fell, more reinforcements, including some led by Ihaka Whaanga of Ngāti Kahungunu, joined them but ammunition was low. Ropata requested some be brought up, but night had fallen and no one wanted to make the climb up in the dark. Ropata abandoned the position early the following morning as his men had run out of ammunition. They then withdrew from Ngatapa altogether, fatigued from the marching and fight of the past several days, and returned to Tūranga.[23][Note 1]

Rumours that Te Kooti had abandoned Ngatapa spread in the days following the engagement there, but then on 12 December Te Kooti led a second lightning raid into Poverty Bay. This saw three settlers killed at Opou, near Tūranga, and a skirmish with some Ngāti Kahungunu followed. Further reports confirming Te Kooti's presence at Ngatapa were received. The raid of 12 December galvanised Whitmore, who had arrived at Tūranga with his Armed Constabulary on 6 December, to renew his campaign against Te Kooti. He had previously decided just days earlier to return to South Taranaki on hearing the rumours that Te Kooti had quit Ngatapa and retired inland. His troops, who had embarked on a ship for South Taranaki, were turned around and planning began for a second, better-equipped assault on Ngatapa.[25][26] Concerned that Te Kooti could still vacate Ngatapa before Whitmore could get there with his men, a contingent of Ngāti Kahungunu had moved off from Wairoa to penetrate the interior and cut off his retreat.[27] In the meantime, Ropata, disappointed with the performance of some of his Ngāti Porou at Ngatapa, went to his home region of Waiapu to recruit more warriors.[24]

Whitmore departed Tūranga with his force on 24 December and three days later was observing Ngatapa from a position, dubbed Fort Richmond, about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) away, having placed a number of depots of stores on his march to make supply of his troops easier. His Armed Constabulary were too few to surround the pā. However, on 30 December, they were joined at Fort Richmond by 300 Ngāti Porou gathered and led by Ropata and Hotene Porourangi. This brought the total forces under Whitmore's command to nearly 700 men; 370 Ngāti Porou and 300 men of the Armed Constabulary, 60 of them Māori of the Te Arawa iwi.[28][29]

Encirclement

The following day, Whitmore moved his force up to the Crow's Nest and erected fortifications. Detachments advanced up the hill towards the pā, digging in under sniper fire. By nightfall, the main approach to Ngatapa was under Whitmore's control although there were still minor pathways through the broken terrain surrounding the pā. In the early hours of 1 January, a large detachment of 200 men cut off the southern approach. Soon afterwards, Ropata with 80 of his Ngāti Porou and the 60 Te Arawa Armed Constabulary began working their way around the base of the hilltop. In doing so, he cut off the streams that formed the pā's water supply. More Armed Constabulary worked around the other side of the hilltop and despite boulders being rolled down the hill at them, cut off the last of the minor pathways off the hilltop. Ngatapa pā was effectively encircled, with only the north side, a high rocky precipice considered far too steep for use as an escape route, left unsecured.[29][30]

Ropata had planned to move upwards from his position when the attack commenced but heavy rain soon fell. This affected the supply arrangements, which had been placed under stress when the Ngāti Porou arrived at Ngatapa without much ammunition. It also delayed Whitmore's attack. In the meantime, there was sniping from the pā which killed two of Ropata's men. On 3 January, Te Kooti's Ringatū warriors made a sortie against the Armed Constabulary holding the western perimeter, astride the narrow and precarious ridge line. In response, Whitmore briefly pounded the pā defences with Coehorn mortars. A relief party helped force the attacking Ringatū back.[29][30][Note 2]

Further attempts were made by the Ringatū to gain access to the water supply, but these too were defeated. The actions of Te Kooti made Whitmore realise that the occupiers of the pā were becoming desperate. The next day, the Te Arawa men of the Armed Constabulary and Ngāti Porou warriors climbed the steep southern side via a route discovered by Ropata's scouts. They then attacked the outer trench and palisades while others in Whitmore's force kept up heavy covering fire. Te Kooti had to withdraw from the trench; the loss of the pā was now almost certain.[29][30]

Escape and pursuit

In the early hours of the morning of 5 January, Te Kooti and the rest of the Ringatū fled the pā. They descended down the steep rock face on the northern side of Ngatapa, lowering themselves more than 20 metres (66 ft) down on vines woven to form a rope. On hearing the cries of one of the female prisoners still inside the pā, yelling that there were no men present, the attackers entered to find mainly women and children left, and wounded men. The latter were immediately killed.[29][30]

No rearguard remained to cover the escape and Ropata's Ngāti Porou and the Te Arawa Armed Constabulary promptly set off in pursuit of the fleeing Ringatū. The European personnel of the Armed Constabulary remained behind; there was concern that they make not be able to tell the difference between the escapees and their pursuers. Te Kooti and his key followers evaded capture but around 130 of his men, weak from hunger and lacking ammunition for defence, were rounded up from the bush and gorges below over the next two days. As many Ngāti Porou were incensed at the murders committed by the Ringatū in Poverty Bay, most of the prisoners were marched up to a cliff and executed on Ropata's orders. Whitmore did nothing to interfere. Some Te Arawa members of the Armed Constabulary also participated in the killings. Around 20 men, some of whom later stood trial for the murders of the settlers at Matawhero, and 135 women and children were made prisoners.[32][33]

Aftermath

The government forces and their kūpapa allies incurred few casualties at Ngatapa, with the Armed Constabulary having five men killed and Ngati Porou six. Te Kooti suffered a major defeat with at least half of his Ringatū warriors, around 130 or so, being killed at Ngatapa or executed in the subsequent pursuit through the bush following their escape from the pā. This was in addition to the 60 or so killed or captured at Makaretu.[34] At least some of the executed were likely to have been Māori captured by Te Kooti in his raids in Poverty Bay rather than Ringatū.[32][33] The historian Matthew Wright noted that Ropata, who ordered the executions, had been captured and enslaved by Te Kooti's Rongowhakaata iwi as a young man and this was a factor in the massacre at Ngatapa.[35]

Te Kooti found refuge in the Urewera ranges with the Tūhoe iwi and from there raided a number of Māori communities that he perceived as being allied to the government. A number of expeditions were mounted to capture him although he was able to evade these. Over time he lost support from Tūhoe due to the impact of punitive expeditions mounted by the government into their land. Te Kooti moved into King Country where he was sheltered by Tāwhiao, the Māori King, until he received a pardon in 1883.[36]

Legacy

In 2004, in a report on land claims in the Poverty Bay and East Cape regions, the Waitangi Tribunal described the executions as "one of the worst abuses of law and human rights in New Zealand's colonial history". It also noted that Te Kooti's actions in killing settlers and Māori in Poverty Bay were a breach of the Treaty of Waitangi and went on to comment that "The horrors of Ngatapa were perpetrated to avenge the horrors of Matawhero".[37] On 5 January 2019, to commemorate the passage of 150 years since the massacre, a pouwhenua (land post) sculpted from totara wood was unveiled near Matawhero by descendants of those killed.[38]

Notes

Footnotes

- Ropata and Preece were subsequently awarded the New Zealand Cross for this action, the recommendation coming from Whitmore.[24]

- Two men of the Armed Constabulary, Benjamin Biddle and Solomon Black, were later awarded the New Zealand Cross for their role in turning back the attackers.[31]

Citations

- Greenwood, William (1946). "Iconography of Te Kooti Rikirangi". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 55 (1). Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- McGibbon 2000, pp. 370–371.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 379.

- Keenan 2021, p. 231.

- Ryan & Parham 2002, pp. 12–14.

- McLauchlan 2017, pp. 161–162.

- O'Malley 2019, p. 211.

- Cowan 1956, pp. 223–224.

- McLauchlan 2017, pp. 163–165.

- O'Malley 2019, pp. 213–214.

- O'Malley 2019, p. 215.

- McGibbon 2000, pp. 32–34.

- Belich 1998, p. 225.

- McLauchlan 2017, pp. 167–168.

- O'Malley 2019, pp. 218–219.

- Belich 1998, p. 228.

- Belich 1998, p. 230.

- Belich 1998, pp. 231–232.

- Crosby 2015, p. 347.

- Cowan 1956, p. 273.

- Belich 1998, pp. 260–261.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 383.

- Crosby 2015, pp. 348–349.

- Cowan 1956, p. 275.

- Crosby 2015, pp. 350–351.

- Belich 1998, p. 262.

- Belich 1998, p. 263.

- Crosby 2015, p. 352.

- Belich 1998, pp. 264–265.

- Crosby 2015, pp. 352–354.

- Cowan 1956, p. 278.

- O'Malley 2019, pp. 223–225.

- Belich 1998, pp. 265–266.

- Cowan 1956, pp. 281–282.

- Wright 2011, p. 203.

- McLauchlan 2017, pp. 171–172.

- "Killings Blamed on Both Sides". New Zealand Herald. 31 October 2004. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- "Dark Days at Ngatapa Recalled". Wateanews.com. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

References

- Belich, James (1998) [1986]. The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-027504-9.

- Cowan, James (1956) [1923]. The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Māori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume II: The Hauhau Wars, 1864–72. Wellington: R.E. Owen. OCLC 715908103.

- Crosby, Ron (2015). Kūpapa: The Bitter Legacy of Māori Alliances with the Crown. Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-357311-1.

- Keenan, Danny (2021) [2009]. Wars Without End: New Zealand's Land Wars – A Māori Perspective. Auckland: Penguin Random House New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-14-377493-8.

- McGibbon, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History. Auckland: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-558376-2.

- McLauchlan, Gordon (2017). A Short History of the New Zealand Wars. Auckland: David Bateman. ISBN 978-1-86953-962-7.

- O'Malley, Vincent (2019). The New Zealand Wars: Nga Pakanga O Aotearoa. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 978-1-988545-99-8.

- Ryan, Tim; Parham, Bill (2002). The Colonial New Zealand Wars. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86934-082-7.

- Wright, Matthew (2011). Guns and Utu: A Short History of the Musket Wars. Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-356565-9.