Siege of Tauromenium (394 BC)

The siege of Tauromenium was laid down by Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, in the winter of 394 BC, in the course of the Sicilian Wars against Carthage. After defeating the Carthaginians at the Battle of Syracuse in 397 BC, Dionysius had been expanding his territory and political influence by conquering Sicel lands and planting Greek colonies in northeastern Sicily. Tauromenium was a Sicel city allied to Carthage and in a position to threaten both Syracuse and Messina. Dionysius laid siege to the city in the winter of 394 BC, but had to lift the siege after his night assault was defeated. Carthage responded to this attack on their allies by renewing the war, which was ended by a peace treaty in 392 BC that granted Dionysius overlordship of the Sicels, while Carthage retained all territory west of the Halykos and Himera rivers in Sicily.

| Siege of Tauromenium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Sicilian Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Syracuse | Tauromenium, Sicily | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Dionysius | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 600+ | Unknown | ||||||

Background

Carthage had intervened in favor of Segesta in 409 BC against Selinus, which led to the sack of both Selinus and Himera in 409 BC. This led to Hermocrates raiding Punic territory, and the retaliation of Carthage saw the destruction of Akragas, Gela and Camarina by 405 BC, when a peace treaty ended the war with Carthage in control of much of Sicily and Dionysius to power in Syracuse. After strengthening Syracuse between 404–398 BC, Dionysius attacked the Phoenician city of Motya with an army of 80,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry, along with a fleet of 200 warships and 500 transports carrying his supplies and war machines in 398 BC, igniting the first of four wars he was to lead against Carthage.[1] After Dionysius sacked Motya, Himilco arrived in Sicily with an army numbering 50,000 men along with 400 triremes and 600 transports.[2]

Himilco first stormed Motya, where the mostly Sicel garrison under Biton was easily overcome,[3] then lifted the siege of Segesta, and Dionysius retired to Syracuse instead of offering battle in western Sicily against a superior army.[4] Himilco returned to Panormus, garrisoned the Carthaginian territories, and then sailed to Lipara and collected 30 talents of silver as tribute.[5] The Carthaginian force next sailed for Messana and easily captured and sacked the city. The occupation of Messana gave the Carthaginians control over the Strait of Messina and a harbor that could house their entire fleet, and also put them in a position to hinder naval traffic between Italy and Sicily. The Greeks had controlled this strategic position since 725 BC. The Carthaginians were also in a position to alley with Rhegion, which was hostile to Syracuse.

Strategic considerations

Himilco chose not to set up base at Messana, he probably was not confident about holding the city this far away from Carthage.[6] Furthermore, majority of the Greeks of Messana were holed up in the hill fortresses nearby, and reducing them required time, which in turn would enable Dionysius to strengthen himself for the coming battle. The ultimate Carthaginian goal was the defeat of Syracuse, Messana was just a sideshow. Bringing reinforcements from Carthage would be time consuming as Carthage had no standing army and would need time to raise fresh mercenaries, while dividing the field army to Guard Messana would decrease his striking power against Dionysius. Himilco on the other hand could not entirely ignore the hostile Greek fortresses in his rear, as they might cause problems once he left the site. His solution was simple and ingenious at the same time, something that is termed indirect approach.[7]

The solution

Himilco chose to plant a city at Mt. Taurus, where some Sicels had already settled,[8] and populated it with allied Sicels and fortified the place, and in doing so killed several birds with a single stone. The city was near enough to block any Greek movements from Messana but was far enough away to fall victim to a surprise attack, and it could serve as a future base of operations. Furthermore, all the Sicels hated Dionysius[9] and except those from Assorus, they now abandoned the Greeks and either joined Himilco or went to their respective homes, decreasing the strength of Dionysius without Carthaginians striking a single blow.

Epaminondas of Thebes in 370 BC used the same strategy when he rebuilt Messene and founded Megalopolis in Spartan territory after failing to take Sparta by force, and decreased their territory and manpower successfully.[7]

Sicels and Greeks: mixed relations

Before Himilco built Tauronemium, Dionysius had permitted the Sicels to settle at Naxos, a nearby Greek city Dionysius had sacked and depopulated, an act that apparently did not impress the Sicels, and they chose to join Himilco at the first opportunity. Their past history with the Greeks may have been a reason.

Naxos was the first Greek colony in Sicily, settled in 734 BC on Sicel land. From that date Sicels had been the victims of Greek aggression. Leontini was the next colony, settled by Naxos, where the Greeks promised to live in peace with the Sicels. The Greeks at Leontini got colonists from Megara (who later founded Megara Hyblea) to drive the Sicels out of that city.[10] On the other hand, Sicels also lived on friendly terms with Greeks, Hippocrates had hired Sicel mercenaries to fight both Sicels and Greeks and slaughtered the Sicel mercenaries when convenient,[11] Sicels and Greeks of Camarina also banded together to fight Syracuse, and much of Greek culture was absorbed by Sicel communities. The Greeks joined hands to defeat Ducetius, a Sicel warlord who tried to create a united Sicel state in the 440s. Dionysius had attacked the Sicels towns of Herbessus,[12] Henna[13] and Herbita[14] prior to starting the war with Carthage, so the Sicels had cause to hate him.[15]

Sicily during 396–394 BC

The Carthaginians moved south towards Catana after the Sicels were secure at Tauromenium.[16] Dionysius moved his forces to Catana also but, due to the rash tactics of his brother Leptines, the Greek fleet was heavily defeated at the naval battle of Catana.[17] The Sicilian Greek cities which had become tributary to Carthage after 405 BC had all revolted in 398 BC, and along with the Sicels and the Sikans had joined Dionysius in his attack against Motya. After the defeat at Catana the Sicilian Greek soldiers returned to their respective homes when Dionysius decided to withstand a siege in Syracuse against their wishes. The Sicels had also turned against Dionysius after the establishment of Tauromenium and had sent soldiers to help Himilco during the siege of Syracuse in 397 BC.

Himilco besieged Syracuse itself in the autumn of 397 BC. After the Carthaginian forces were devastated by a plague, Dionysius managed to decimate the Punic fleet and shut up the army survivors in their camp in the summer of 396 BC. Himilco, after bribing Dionysius, fled to Africa with Carthaginian citizens, while Dionysius enslaved the abandoned Carthaginian soldiers.

Carthage: plagued by problems

The return of Himilco after abandoning his troops at the mercy of Dionysius did not sit well with the Carthaginian citizens or their African subjects. Himilco publicly took full responsibility for the debacle, dressed in rags visited all the temples of the city pleading for deliverance and finally committed suicide.[17] The divine was not mollified as a plague swept through Africa weakening Carthage further, and to top things off, the Libyans, angered by the desertion of their kinsmen in Sicily, gathered an army numbering 70,000 men and besieged Carthage itself.

Mago, the victor of Catana, (and possibly a member of the Magonid family)[18] took command. The standing Punic army was in Sicily and recruiting a new one would have been time consuming and probably very costly (Himilco's abandonment of mercenaries would have made mercenaries wary), so he rallied Carthaginian citizens to man the walls while the Punic navy kept the city supplied, as the Libyans had no ships to counter the Carthaginian fleet. Mago then used bribes and other means to quell the rebels.[17]

Mago in Sicily

After securing the safety of Carthage, Mago moved to Sicily, where the Punic city of Solus had been sacked by Dionysius sometime in 396 BC. Carthage was unwilling or unable to provide Mago with additional forces, and he had to make do with the Punic garrison left by Himilco and whatever forces he could gather in Sicily.[19] The Carthaginians caught a break when Dionysius chose not to invade the Punic territories in western Sicily immediately lifting the siege of Syracuse. The Elymians had stayed loyal to Carthage since the start of the war, while the Sicilian Greeks and Sikans were not threatening and most of the Sicels were not hostile when Mago arrived in Sicily.

Instead of trying to recover the lost Punic conquests through force, Mago adopted a policy of cooperation and friendship, giving aid to Greeks, Sikans, Sicels, Elymians and Punics regardless of their prior standing with Carthage.[9] Many of the Greeks had been victims of the duplicity and aggression of Dionysius (he had destroyed Greek cities Naxos, Leontini and Catana and driven out the population) and even preferred to live under Punic rule.[20]

The Carthaginians allowed Greeks from Naxos, Catana and Leontini, made refugees by Dionysius, along with Sicels and Sikans to settle in Punic territory, while alliances were made with Sicel tribes being threatened by Dionysius.[21] The Greeks cities, free of Carthaginian over lordship since 398 BC, now moved from a pro Syracuse position to a neutral one, either feeling threatened by Dionysius or because of the activities of Mago.[22]

Syracuse: Dionysius secures position

Dionysius did not immediately attack Punic Sicily after lifting the siege of Syracuse in 396 BC, although no formal treaty had been made ending the war with Carthage. The war had been costly and he may have been short of money, he also had to deal with a revolt of his mercenaries, and furthermore, he feared a fight to the finish with Carthage as it might end up finishing him.[23] After securing Syracuse and resettling the rebellious mercenaries at Leontini (or having them killed after taking them to Leontini in the pretext of handing the town to them),[24] Dionysius began to secure his position in eastern Sicily.

Campaigns of Dionysius

The city of Rhegion, which is situated across Messana in the Italian mainland, was hostile to Dionysius because the tyrant was responsible for the destruction of Naxos, Catana and Leontini, fellow Ionian Greek cities of Sicily. Rhegion had aided the Syracusan rebels[25] in 403 BC against Dionysius (ironically Carthage helped bail Dionysius out) and had launched an unsuccessful campaign against Syracuse in 400 BC.[26] Furthermore, Dionysius held a personal grudge: The citizens of Rhegion told him to marry their hangman's daughter when he sought a wife from Rhegion.[27] The destruction of Messana had left Rhegion in a position to dominate the Strait of Messina, and Carthage with an opportunity to join hands with Rhegion and threaten Syracuse from the north, just as Anaxilas of Rhegion had done in 480 BC against Syracuse before the 1st battle of Himera.

Securing the north

Dionysius chose not to attack Carthaginians in western Sicily while the threat of Rhegion forcing a two front war on him existed, instead he rebuilt and repopulated Messana with 1,000 colonists from Locri and 4,000 Medma from Italy[28] and some from Messene in mainland Greece, who were later relocated to Tyndaris when Sparta objected to settling the Messenians in Messana.[29] The original inhabitants of Messana, homeless since the sack of their city in 397 BC, were settled at Tyndaris, another city built by Dionysius after he forced the Sicel city of Abacaenum to cede lands to the new colony in 395 BC, which eventually housed 5,000 citizens.[30] The founding of Messana and Tyndaris helped secure the north eastern coast of Sicily for Dionysius. Rhegion, fearing Dionysius might use Messana as a base against them, planted the Greek colony of Mylae between Messana and Tyndaris and populated the city with the refugees of Naxos and Catana,[31] thus reducing the territory of Messana. The colonists of Mylai, aided by Rhegion and led by the exiled Syraccusan general Heloris, attacked the acropolis of Messana, but the Mesanians, aided by some mercenaries of Dionysius, were victorious; the Messanians then attacked Mylae, which surrendered, the inhabitants were allowed to leave, and many took refuge with the Sicels.[32]

Prelude to Tauromeniun

Dionysius attacked the Sicels and took Smeneous (exact location unknown) and Morgantina, around which the Punic city Solus and Sicel city Cephaleodium were betrayed to him, and the Sicel town Enna was sacked with the booty used to fatten his coffers.[29] Syracusan territory by now had expanded to border Agyrium. Agyris, tyrant of Agyrium was a ruthless man, having become rich after killing the leading citizens of Agyrium, commanded 20,000 citizens and many fortresses and was second only to Dionysius in Sicily.[33] Furthermore, Agyris had aided the Campanian mercenaries sent by Carthage to rescue Dionysius in 403 BC (when the Greek rebels had him besieged in Syracuse and he was close to capitulating),[34] so Dionysius had a personal debt to consider.

Sicel allies of Syracuse

Dionysius chose not to provoke Agyris or Damon, ruler of Centuripae but made alliances with the Sicel cities of Agyrium, Centuripae, Herbita, Assorus (this city had stayed loyal to Syracuse after other Sicels had deserted to Himilco when Tauromenium was founded in 397 BC)[35] and Herbessus,[29] creating a buffer zone for Syracuse in central Sicily. Thus having created a buffer in Central Sicily, Dionysius resolved to deal with Rhegion. Tauromenium was sitting between the territory controlled by Syracuse and could hinder Syracusan army/fleet movements, so Dionysius chose to attack the enemy nearest to Syracuse first in the winter of 394 BC.[31]

Opposing forces

Dionysius had mustered an army of 40,000 foot and 3,000 horsemen,[36] from both citizens and mercenaries (at least 10,000, if not more)[37] for attacking Motya in 398 BC, perhaps along with 40,000 Greek, Sicel and Sikan volunteers.[38] At Catana in 397 BC Dionysius commanded 30,000 foot and 3,000 horse, perhaps he was short of cash to hire mercenaries and part of his forces were manning Syracuse. The exact size of the Greeks army in 394 BC is not known, nor is the role played by the Greek fleet.

Greek forces

The mainstay of the Greek army was the Hoplite, drawn mainly from the citizens by Dionysius had a large number of mercenaries from Italy and Greece as well. Sicels and other native Sicilians also served in the army as hoplites and also supplied peltasts, and a number of Campanians, probably equipped like Samnite or Etruscan warriors,[39] were present as well. The phalanx was the standard fighting formation of the army. The cavalry was recruited from wealthier citizens and hired mercenaries. Dionysius also had the services of a number of Iberian troops, former members of Himilco's army. The Iberian infantry wore purple bordered white tunics and leather headgear. The heavy infantry fought in a dense phalanx, armed with heavy throwing spears, long body shields and short thrusting swords.[40] Dionysius probably had an army which was predominantly made of mercenaries, as Greek citizens liked short campaigns and were reluctant to fight during off season.[41]

Sicel warriors

The number of Sicels soldiers present at Tauromenium is not known. Large Sicilian cities like Syracuse and Akragas could field up to 10,000–20,000 citizens,[42] while smaller ones like Himera and Messana between 3,000[43]–6,000[44] soldiers. Tauromenium probably could field a similar numbers like Messana.

The Sicels may have come from Italy[45] and their forces may have displayed Oscan influence. The Sicel tribes lived in villages around a hilltop fort, their citizen force probably built around units of 100 like the Oscans and Latins. Sicel soldiers armed themselves, and may have adopted some Greek style equipment. Poorer citizens formed the infantry while wealthier citizens the cavalry. Like the Samnites,[46] Sicels probably had troops armed with 2 javelins (for poking and throwing), while some may have carried longer spear for thrusting, while hide covered round shields carried by both type of troops, who also wore helmets, shin guards and a square breastplate, with wide belts protecting their middle. Some Sicels may have borrowed the cuirass, kepis and greaves from the Greeks. Cavalry wore bronze armour and carried swords and lances.[47]

Sicels may have favored open order ambushes and raids in their mountain homeland, but also formed battle lines when needed with the javelinmen in front and lancers backing them up and cavalry protecting the flanks.[47] Light troops were also used, and in sieges women and children could be sued as impromptu peltasts hurling tiles, bricks and other missiles.

Beginning of campaign

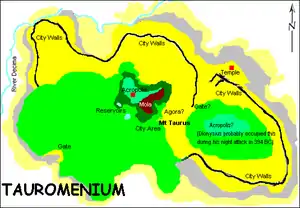

The Syracusan army approached the city from the south and encamped at the ruins of Naxos and set about cutting off the access to the city.[31] The Sicels put up a stubborn defence; the city was perched on cliffs which were not accessible by siege engines unless siege ramps could be built. Dionysius was not interested in starving the Sicels out and set about planning an assault of the city.

Dionysius chose to attack, extend the siege in winter, which was unusual in ancient times as it often meant combating both the elements and the enemy; logistics were also a prime concern as the scope for foraging (crops were not ready for harvest) was limited. However, Dionysius may have based his decision on the fact that the Carthaginians and Rhegians, most likely source of help for the Sicels, would not be prepared for a winter campaign, and the Sicels would be caught off guard as well.

Defenses at Tauronemium

The city of Tauromenion was built atop the 200 m high Mt. Taurus, surrounded by ravines and walls that covered the most vulnerable places. The main acropolis was built on the highest point and overlooks the town, being 212 m from sea level. The Sicel town is said to have another acropolis, which probably occupied the place of the Greek Theater. The western gate of the city was situated on the south wall. The city overlooked the site of Naxos, which was the first Greek colony in Sicily, and from that place the aggression of the Greeks against Sicels began. The Sicels were determined to hold on to Tauromenium, which was a gift from Carthaginians who had never attacked them, and had enabled them to recapture the lands of their forefathers.[22]

Night commando

The most famous siege in Greek history, that of Troy, was resolved by a night attack. Dionysius was no stranger to night operations, having twice pulled off the feat at Motya and Syracuse. He had nothing like the Trojan Horse to dupe the Sicels with and was about to find out third time may not be "charmed" for him.

The Sicels had refused to contest the siege openly so the Greeks settled in at Naxos. The snow covered the heights of Mt. Taurus as the winter solstice approached, and the Greeks observed that the guard was slack on one of the forts of Tauromenium.[22] Dionysius chose a moonless, stormy night to scale the walls of the fortress, probably situated on the peak where the Greek Theatre now stands, with a picked group of mercenaries. The cold and the jagged sides of the cliff took their toll in the dark and Dionysius suffered cuts to his face, but the detachment managed to successfully scale the heights and take possession of the acropolis without difficulty.

Urban warfare

If Dionysius hoped to avoid a fierce urban battle by launching a surprise attack he failed, because just as the Greeks entered the town led by Dionysius the Sicels woke up and began to gather; more soldiers from the Acropolis on Mt. Taurus swelled their ranks and they launched a counterattack. The soldiers of Dionysius, probably tired from their arduous climb, got clobbered, 600 Greeks were immediately cut down and the Sicels sent the survivors tumbling down the side of the mountain. As the Greeks rolled or scrambled down the sides many lost their armor. Dionysius was one of the few who retained their breastplate – a small consolation but a matter of pride for him. Tauromenium remained untaken; Dionysius packed up and went home.

Aftermath

The defeat at Tauromenium had serious consequences. The Greek cities of Akragas and Messana deposed the supporters of Dionysius from power when the news of the debacle became known. The situation worsened when Mago gathered up his forces and raided Messana, but Dionysius defeated the Carthaginians at the Abacaenum to prevent further damage befalling him. Tauromenium remained free for 2 more years before falling victim to super power politics. Caught in a jam at the Battle of Chrysas in 392 BC, both Mago and Dionysius agreed to terms formally concluding the war which started in 398 BC. One on the conditions was Carthage agreeing to Syracusan over-lordship of Sicels. Dionysius occupied Tauromenium in 391 BC, expelled the Sicels and installed his mercenaries on the site. In 358 BC a Greeks town was founded there, and it remained Greek until passing into Roman hands. After settling his affairs in Sicily, Dionysius began a campaign against Rhegion in 390 BC. He failed to take the city in 390 and 389 BC and finally succeeded in 387 BC. Three years later, again he started a war with Carthage that lasted until 375 BC and ended in his defeat.

Bibliography

- Warry, John (1993). Warfare in The Classical World. Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-56619-463-6.

- Lancel, Serge (1997). Carthage A History. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-57718-103-4.

- Kern, Paul B. (1999). Ancient Siege Warfare. Indiana University Publishers. ISBN 0-253-33546-9.

- Church, Alfred J. (1886). Carthage, 4th Edition. T. Fisher Unwin.

- Freeman, Edward A. (1894). History of Sicily Vol. IV. Oxford Press.

- Caven, Brian (1990). Dionysius I: War-Lord of Sicily. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04507-7.

- Ray, Fred Eugene. (2008). Land Battles in 5th Century BC Greece. McFarland & Co. Inc. Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-3534-0.

Further reading

- Baker, G. P. (1999). Hannibal. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1005-0.

- Bath, Tony (1992). Hannibal's Campaigns. Barns & Noble. ISBN 0-88029-817-0.

- Bath, Tony (1992). Hannibal's Campaigns. Barns & Noble. ISBN 0-88029-817-0.

- Freeman, Edward A. (1892). Sicily Phoenician, Greek & Roman, Third Edition. T. Fisher Unwin.

References

- Church, Alfred J., Carthage, p47

- Caven, Brian, Dionysius I, pp107

- Diod. X.IV.55

- Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp183

- Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, pp173

- Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp184

- Hart, B.H. Liddle, Strategy 2nd Edition, pp15

- Diod. X.IV.59

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.90

- Polyneaus V.5.1

- Polyneaus V.6.1

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.7

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.14

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.15

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.58

- Freeman, Edward A., Sicily, p173

- Church, Alfred J., Carthage, p53-54

- Lancel, Serge., Carthage A History, pp114

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol IV, p169

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol. 4, pp58 – pp59

- Diod. X.IV.90

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.88

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol. 4, pp149 – pp151

- Polyainos V.2.1

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.8

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.40-41

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.44, X.IV.07

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol IV, pp152

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.78

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily, pp 153- pp156

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.87

- Diodorus Siculus X.IV.87

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.95

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol. 4, pp18 – pp21

- Freeman, Edward A., History of Sicily Vol. 4, pp107

- Caven, Brian, Dionysius I, p93

- Kern, Paul B., Ancient Siege Warfare, pp178

- Diodurus Siculus, X.IV.47

- Warry, John, Warfare in the Classical Age, pp103

- Goldsworthy, Adrian, The Fall of Carthage, p 32 ISBN 0-253-33546-9

- Freeman, Edward A, History of Sicily Vol. IV, pp164

- Diodorus Siculus, X.III.84

- Diodorus Siculus, X.IV.40

- Diodorus Siculus XIII.60

- Thucidides, 3.103.1

- Warry, John, Warfare in the Classical Age, pp 103

- Ray, Fred Eugene, Land Warfare in 5th Century BC Greece, pp 53-54

External links

- Diodorus Siculus translated by G. Booth (1814) Complete book (scanned by Google)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)