Sikkim expedition

The Sikkim expedition (Chinese: 隆吐山戰役; pinyin: Lóng tǔshān zhànyì; lit. 'Battle of the Lingtu Mountain') was an 1888 British military expedition to expel Tibetan forces from Sikkim in present-day northeast India. The roots of the conflict lay in British-Tibetan competition for suzerainty over Sikkim.

| Sikkim expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

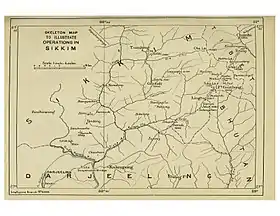

The theatre of war in Sikkim | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Lingtu | |

|---|---|

Lingtu | |

| Highest point | |

| Coordinates | 27°16′08″N 88°47′34″E |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Himalaya |

Causes

Sikkim had a long history of relations with Tibet. Buddhism was the state religion and its Chogyal rulers were descended from Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, a Tibetan saint who unified Bhutan. In the first half of the 19th century, the British extended their influence to the Himalayas and Sikkim signed the Treaty of Tumlong with the British in 1861. As the British established relations with Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan, Tibetan influence waned and in Lhasa and Peking it was feared that if left unopposed, the British would encroach into Tibet through Sikkim.

Thutob Namgyal, the 9th Chogyal of Sikkim, looked to the Dalai Lama for spiritual leadership and during his reign the Tibetan government started to regain political influence over Sikkim. Under the 1861 treaty, the Chogyal was restricted to spending no more than three months in Tibet but he frequently ignored this provision and in 1887, after having resided for almost two years in Tibet he declined to travel to Darjeeling to meet with the Lieutenant-Governor arguing that the Amban in Lhasa had forbidden him to do so.[1] Meanwhile, he had ordered that the revenue collected be sent to Chumbi, a clear sign of his intention not to return to Sikkim.[1]

In 1884 the Indian government prepared to send a diplomatic mission to the Tibetan capital Lhasa to define the spheres of influence of the Tibetan and Indian governments. Colman Macaulay was to be the responsible for the negotiations but the mission was indefinitely postponed after the Tibetan government dispatched an expedition of 300 soldiers that crossed the Jelep La pass and occupied Lingtu around 13 miles (21 km) into Sikkim.

The British decided to suspend the Macaulay mission since its presence was the Tibetan's argument for their occupation. However, instead of retreating the Tibetans showed every sign of being there to stay. They built a fortified gate on the road that crossed Lingtu coming from Darjeeling and into Tibet, and also constructed a fort for its defence. After negotiations with the Chinese stalled, the Indian government ordered the despatch of a military expedition to Lingtu to restore Indian control of the road.

Despatch of the Expedition

Starting in 1888, while negotiations carried on the British prepared for a military solution. In January they sent to the frontier the headquarters and one wing of the 32nd Pioneers to repair the Rongli bridge and the road, and prepared resting locations for the expedition at Sevoke and Riang in the Terai.[1] The Tibetan government received an ultimatum to withdraw their troops by 15 March.[2]

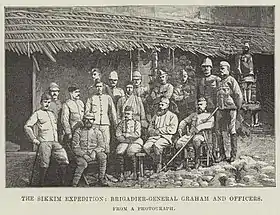

On 25 February Brig-Gen Thomas Graham RA was ordered to march. His forces mustered the 2nd Battalion Derbyshire Regiment, HQ wing 13th Bengal Infantry, four guns from the 9-1st Northern Division Royal Artillery and the 32nd Pioneers.[2] His orders were to expel the Tibetans from Lingtu and reestablish Indian control of the road up to the Jelep La, while securing Gantok and Tumlong from possible reprisals. He was not instructed to cross into Tibet but the decision was left to his discretion.

An advanced depot was established at Dolepchen and the entire force was assembled at Padong by 14 March when it was divided into two columns, the Lingtu column commanded by Graham and the Intchi column by Lt-Col Mitchell.

Jeluk and Lingtu

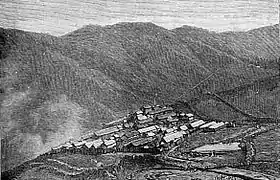

_p084_WAY_TO_SEDONGCHEN.jpg.webp)

Mitchell sent 200 men to Pakyong while he remained in Padong.[3] Graham advanced to Sedongchen, about 7 miles (11 km) from Lingtu, on the 19th and the next day he attacked the Tibetan stockade at Jeluk.[3] The Tibetans had barricaded the road and erected a stockade on a hill that dominated the road. Graham advanced up the road with the pioneers in front clearing the path from bamboo and foliage, followed by a hundred men of the Derbyshire and the two artillery pieces.[3] The advance was slow due to the difficult terrain, but once they reached the stockade the Tibetans retreated after a short struggle. In spite of the fortifications the defenders' bows and matchlocks were outgunned by the British modern rifles and artillery. After carrying the stockade, the British drove the defenders off a stone breastwork that covered the back of the stockade and stopped short their pursuit of the retreating Tibetans.[4]

After the battle of Jeluk, Graham reformed his men and advanced down the road as far as Garnei, within a mile of the Lingtu fort, and camped there for the night.[4] The next morning the column advanced slowly through the mist and snow to the Tibetan positions and around 11 o'clock the 32nd Pioneers occupied the gate of the fort which was guarded only by some 30 Tibetan soldiers.[5]

Gnathong

After escaping from Lingtu, the Tibetans crossed the border and rallied in the Chumbi valley, defeated but not destroyed. In fact they received reinforcements and the British readied their defences in Gnathong, a plateau some three or four miles north of Lingtu.[6] On 21 May the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal arrived at Gnathong and the Tibetans attacked the British defences the next day at 7 AM with 3,000 men (British claim).[6] The fighting lasted until 10 a.m. when the Tibetans retreated. The British admitted three killed and eight wounded and claimed to have killed around a hundred Tibetans.[6] The Tibetans retreated back across the Jelap La and no other combat took place, so in June the British started to send some of the troops back to Darjeeling.[7]

Renewed operations

Towards the end of July, as the British withdrawal continued, renewed Tibetan activity was observed on the other side of the border.[7] The Tibetans were fortifying the mountain passes above the Chumbi valley. Colonel Graham had at his disposition only 500 men plus a garrison at Gnathong, while the Bengal government estimated the Tibetan strength between Rinchingong and Kophu at 7,000, plus a reserve at Lingamathang of 1,000 soldiers.[7] Quickly the Bengal authorities sent reinforcements and by the end of August, Graham's forces at Gnathong had risen to 1,691 soldiers and four guns.[7]

After some skirmishes, the Tibetans crossed the Tuko La pass some two miles from Gnathong. Quickly they started building a wall on the ridge of the pass, some three or four feet high and almost four miles wide.[8] Colonel Graham attacked the Tibetan positions around 8 a.m. with three columns. He led the left column, which attacked the blockhouse that guarded the Tuko La pass. Lieutenant-Colonel Bromhead commanded the centre column that was to advance up the main road to Tuko La. The right column, commanded by Major Craigie-Halkett, was to occupy the saddle-back north east of Woodcock hill and hold the Tibetans' left.[8] Around 9:30 am the attack was opened with the bombardment of the Tibetan left flank by the artillery of the British right. At 10:30 the other two British columns were in contact with the Tibetans, and the British penetrated the defences and captured the Tuko La pass, after which the Tibetans retreated through the Nim La pass.[9] After securing his flanks, Colonel Graham moved to attack the Tibetans at the Jelep La pass which was attacked at 2:00 pm and captured shortly afterwards.[10] The next day the pursuit continued and by 4:00 pm the British had occupied Rinchingong.[11]

Chumbi Valley and Gangtok

The next day, 26 September, the British advanced 3 miles (4.8 km) along the Ammo Chu, and bivouacked for the night at Myatong (Yatung).[11] The Tibetans were disorganized and did not oppose the enemy's progress.

Meanwhile, Graham found it necessary to advance to Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim, where the pro-Tibetan party had ousted the pro-Indian opposition. Colonel Mitchell, with 150 men from the 13th Bengal Infantry, marched to the city on the 23 September.[11]

Convention of Calcutta

After the advance on Chumbi and Gangtok, military operations stalled. On 21 December, the Chinese resident in Lhasa arrived at Gnathong and negotiations began, but no agreement was reached so the Amban returned to Rinchingong where he received orders to wait for Mr. T. H. Hart, of the Chinese Imperial Customs Service, who finally arrived to Gnathong on 22 March 1889.[12] Eventually the Anglo-Chinese Convention of Calcutta was signed on 17 March 1890 at Kolkata, which established the Tibetan renunciation of suzerainty over Sikkim, and delimited the border between Tibet and Sikkim.[12]

See also

Notes

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 50.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 51.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 52.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 53.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 54.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 55.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 56.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 57.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 58.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 59.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 60.

- Paget, Frontier and Overseas Expeditions (1907), p. 61.

References

- Scholarly sources

- Kiernan, V. G. (March 1955), "India, China and Sikkim: 1886-1890", The Indian Historical Quarterly, 31: 34–41 – via archive.org

- Marshall, Julie G. (2005). Britain and Tibet 1765–1947: A select annotated bibliography of British relations with Tibet and the Himalayan states including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. Routledge. ISBN 9780415336475.p. 212.

- Matteo Miele, The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: The Bhutanese Role, West Bohemian Historical Review, 2018, VIII, 2.

- Singh, Amar Kaur Jasbir (1988), Himalayan Triangle: A historical survey of British India's relations with Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan, 1765-1950, British Library, ISBN 9780712306300

- Yi, Meng Cheng (October 2021), "Expedition turned Invasion: The 1888 Sikkim Expedition through British, Indian and Chinese eyes", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 31 (4): 803–829, doi:10.1017/S1356186321000018, S2CID 234852375

- Historical sources

- Iggulden, Herbert Augustus (1900). The 2nd Battalion Derbyshire Regiment in the Sikkim Expedition of 1888. London, S. Sonnenschein & co. – via archive.org.

- Macaulay, Colman (1885). Report of a Mission to Sikkim and the Tibetan Frontier: With a memorandum on our relations with Tibet. Bengal Secretariat Press – via archive.org.

- Paget, William Henry (1907). Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India. Simla: Government Monotype Press – via archive.org.