Silent Sentinels

The Silent Sentinels, also known as the Sentinels of Liberty,[1][2][3] were a group of over 2,000 women in favor of women's suffrage organized by Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, who nonviolently protested in front of the White House during Woodrow Wilson's presidency starting on January 10, 1917.[4] Nearly 500 were arrested, and 168 served jail time.[1][2][3] They were the first group to picket the White House.[1][3] Later, they also protested in Lafayette Square, not stopping until June 4, 1919 when the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed both by the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Sentinels started their protest after a meeting with the president on January 9, 1917, during which he told the women to "concert public opinion on behalf of women's suffrage."[5] The protesters served as a constant reminder to Wilson of his lack of support for suffrage. At first the picketers were tolerated, but they were later arrested on charges of obstructing traffic.

The name Silent Sentinels was given to the women because of their silent protesting, and had been coined by Harriot Stanton Blatch.[6] Using silence as a form of protest was a new principled, strategic, and rhetorical strategy within the national suffrage movement and within their own assortment of protest strategies.[5] Throughout this two and a half year long vigil, many of the women [7] who picketed were harassed, arrested, and unjustly treated by local and US authorities, including the torture and abuse inflicted on them before and during the November 14, 1917, Night of Terror.

Background

The Silent Sentinels' protests were organized by the National Women's Party (NWP), a militant women's suffrage organization. The NWP was first founded as the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CUWS) in 1913 by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns following their organizing of NAWSA's woman suffrage parade in Washington DC in March 1913.[8] CUWS by definition was an organization that took a militant approach to women's suffrage and broke away from the more moderate National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[8] CUWS only lasted for three years until its founders merged it with the Woman's Party to form the National Woman's Party.[8] The National Woman's Party boasted fewer members than National American Woman Suffrage Association(having 50,000 members to NAWSA's million),[7] but its tactics were more attention-grabbing and harnessed more media coverage. The NWP's members are known primarily for picketing the White House and going on hunger strikes while in the jail or workhouse.

The Suffragist

The Suffragist was the National Woman's Party weekly newsletter. The Suffragist acted as a voice for the Silent Sentinels throughout their vigil. It covered the Sentinels' progress and included interviews with protesters, reports on President Woodrow Wilson's (non) reaction, and political essays.[4] While the Sentinels were in prison, a few members wrote about their experiences which were later posted in The Suffragist. "Although The Suffragist was intended for mass circulation, its subscription peaked at just over 20,000 issues in 1917. Most copies went to party members, advertisers, branch headquarters, and NWP organizers, which strongly suggests that the suffragists themselves were a key audience of the publication."[5]

Banners

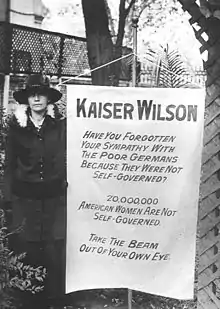

The following are examples of banners held by the women:

- "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?"[5]

- "Mr. President, what will you do for woman suffrage?"[5]

- "We shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments."[9]

- "The time come to conquer or submit, for us there can be but one choice. We have made it." (another quotation from Wilson)

- "Kaiser Wilson, have you forgotten your sympathy with the poor Germans because they were not self-governed? 20,000,000 American women are not self-governed. Take the beam out of your own eye." (comparing Wilson to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and to a famous quote of Jesus regarding hypocrisy)

- "Mr. President, you say liberty is the fundamental demand of the human spirit."[5]

- "Mr. President, you say we are interested in the United States, politically speaking, in nothing but human liberty."[5]

The Sentinels all wore purple, white, and gold sashes which were the NWP's colors. Their banners were also usually colored this way.[5]

Responses

The public's responses to the Silent Sentinels were varied.

Some people wholeheartedly approved of the work Silent Sentinels were performing. Men and women present at the scene of the White House showed their support for the Sentinels by bringing them hot drinks and hot bricks to stand on. Sometimes, women would even assist in holding up the banners. Other ways of showing support included writing letters praising the Sentinels to The Suffragist and donating money.[10]

On the other hand, some disapproved of Silent Sentinels' protests. This included some of the more moderate suffragists. For example, Carrie Chapman Catt- then the leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association - believed that the best way to realize women's suffrage was to gain the vote through individual states first, upon which women could vote for a pro-suffrage majority in Congress. Until late 1915, she thus opposed advocating for a national amendment to grant women's suffrage, as the NWP did.[7] Members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association feared that pickets would create a backlash from male voters.[10]

Anti-suffragists also opposed the Silent Sentinels' protest. Mobs sometimes attempted to deter the Silent Sentinels through violence (which increased after US entry into World War I). For example, some attacked the Silent Sentinels and tore their banners to shreds. This occurred especially with the more provocative banners, such as banners calling Woodrow Wilson "Kaiser Wilson."[7]

At first President Wilson was not very responsive to the women's protest. At points he even seemed amused by it, tipping his hat and smiling. It was said that at one point Wilson even invited them in for coffee; the women declined.[11] At other points in time, he ignored the protests altogether, such as when the Sentinels protested on the day of his second inauguration ceremony.[12] As the Sentinels continued to protest, the issue became bigger and Wilson's opinion began to change. Although he continued to dislike the Silent Sentinels, he began to recognize them as a group seriously presenting him with an issue.[13]

Occoquan Workhouse and the Night of Terror

On June 22, 1917, police arrested protesters Lucy Burns and Katherine Morey on charges of obstructing traffic because they carried a banner quoting from Wilson's speech to Congress: "We shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments." On June 25, 12 women were arrested, including Mabel Vernon and Annie Arniel from Delaware, again on charges of obstructing traffic. They were sentenced to three days in jail or to pay a $10 fine. They chose jail because they wanted to show commitment to their cause and their willingness to sacrifice their physical bodies. On July 14, 16 women, including Matilda Hall Gardner, Florence Bayard Hilles, Alison Turnbull Hopkins, and Elizabeth Selden Rogers (of the politically powerful Baldwin, Hoar & Sherman family) were arrested and sentenced to 60 days in jail or to pay a $25 fine.[14] Again, the women chose jail. Lucy Burns argued that the women should be treated as political prisoners, but that designation had never been used in America.

When the number of women being arrested surpassed the resources of the District of Columbia Jail, the prisoners were taken to Virginia's Occoquan Workhouse (now the Lorton Correctional Complex). Once there, they were asked to give up everything except for their clothing. They were then taken to a showering station where they were ordered to strip naked and bathe. There was only one bar of soap available for everyone in the workhouse to use, so all of the suffragists refused to use it. Afterwards they were given baggy, unclean, and uncomfortable prison clothes and taken to dinner. They could barely eat dinner because it was so sour and distasteful.[14]

The conditions of the District Jail and the Occoquan Workhouse were very unsanitary and unsafe. Prisoners had to share cells and many other things with those who had syphilis, and worms were frequently found in their food.[14]

After a heated debate, the House of Representatives created a committee to deal with women's suffrage in September 1917. Massachusetts Representative Joseph Walsh opposed the creation of the committee, thinking the House was yielding to "the nagging of iron-jawed angels." He referred to the Silent Sentinels as "bewildered, deluded creatures with short skirts and short hair."[15] On September 14, Representative Jeannette Rankin took the chair of the Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage to visit the activists in the Workhouse and the next day, the committee sent on the suffrage amendment bill to the Senate.[16]

As the suffragists kept protesting, the jail terms grew longer. Finally, police arrested Alice Paul on October 20, 1917, while she carried a banner that quoted Wilson: "The time has come to conquer or submit, for us there can be but one choice. We have made it." She was sentenced to seven months in prison. Paul and others were sent to the District Jail and many others were again sent to the Occoquan Workhouse. Paul was placed in solitary confinement for two weeks, with nothing to eat except bread and water. She became weak and unable to walk, so she was taken to the prison hospital. There, she began a hunger strike, and others joined her.[14]

In response to the hunger strike, the prison doctors forcefed the women by putting tubes down their throats.[14] They forcefed them substances that would have as much protein as possible, like raw eggs mixed with milk. Many of the women ended up vomiting because their stomachs could not handle the protein. One physician reported that Alice Paul had "a spirit like Joan of Arc, and it is useless to try to change it. She will die but she will never give up."[17]

A large number of Sentinels protested the forcefeeding of the suffragists on November 10 and around 31 of these were arrested and sent to Occoquan Workhouse.[18] On the night of November 14, 1917, known as the "Night of Terror", the superintendent of the Occoquan Workhouse, W.H. Whittaker, ordered the nearly forty guards to brutalize the suffragists. They beat Lucy Burns, chained her hands to the cell bars above her head, then left her there for the night.[19] They threw Dora Lewis into a dark cell and smashed her head against an iron bed, which knocked her out. Her cellmate, Alice Cosu, who believed Lewis to be dead, suffered a heart attack. Dorothy Day, who later co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement, was slammed repeatedly over the back of an iron bench. Guards grabbed, dragged, beat, choked, pinched, and kicked other women.[20]

Newspapers carried stories about how the protesters were being treated.[21] The stories angered some Americans and created more support for the suffrage amendment. On November 27 and 28, all the protesters were released, including Alice Paul, who spent five weeks in prison. Later, in March 1918, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated six suffragists' convictions.[22][23] The court held that the informations on which the women's convictions were based were overly vague.[22]

Decision

On January 9, 1918, Wilson announced his support for the women's suffrage amendment. The next day, the House of Representatives narrowly passed the amendment but the Senate refused to even debate it until October. When the Senate voted on the amendment in October, it failed by two votes. And in spite of the ruling by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, arrests of White House protesters resumed on August 6, 1918.

To keep up the pressure, on December 16, 1918, protesters started burning Wilson's words in watch fires in front of the White House. On February 9, 1919, the protesters burned Wilson's image in effigy at the White House.[24]

On another front, the National Woman's Party, led by Paul, urged citizens to vote against anti-suffrage senators up for election in the fall of 1918. After the 1918 election, most members of Congress were pro-suffrage. On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the amendment, and two weeks later on June 4, the Senate finally followed. With their work done in Congress, the protesters turned their attention to getting the states to ratify the amendment.

It was officially ratified on August 26, 1920, shortly after ratification by Tennessee, the thirty-sixth state to do so. The Tennessee legislature ratified the 19th Amendment by the single vote of a legislator (Harry T. Burn) who had opposed the amendment but changed his position after his mother sent him a telegram saying "Dear Son, Hurrah! and vote for suffrage. Don't forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the 'rat' in ratification."[25][26]

Popular culture

The Silent Sentinels vigil was a key part of the 2004 film Iron Jawed Angels.[27][28]

See also

- History of women's suffrage in the United States

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Prison Special

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

- Women's Suffrage organisations

- Mud March, 1907 suffrage procession in London

- Women's Sunday, 1908 suffrage march and rally in London

- Women's Coronation Procession, 1911 suffrage march in London

- Suffrage Hikes, 1912 to 1914 in the US

- Woman Suffrage Procession, 1913 suffrage march in Washington, D.C.

- Great Pilgrimage, 1913 suffrage march in the UK

- Selma to Montgomery march, 1965 suffrage march in the US

References

- "The Woman Suffrage Timeline". The Liz Library. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "Woodrow Wilson: Women's Suffrage". PBS. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "PSI Source: National Woman's Party". McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda. The National Woman's Party and the Silent Sentinels. University of Maryland. pp. 144–145.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda A. (2007). "Militancy, power, and identity: The Silent Sentinels as women fighting for political voice". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 10 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1353/rap.2008.0003. JSTOR 41940153. S2CID 143290312.

- Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 44.

- "Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman's Party Campaign". Library of Congress.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda A. (2011). Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913–1920. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-60344-281-7.

- Wilson, Woodrow. Address to Joint Session of Congress. Congress.

- Walton, Mary (2010). A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-230-61175-7.

- "Wilson: A Portrait : Women's Suffrage". PBS. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda A. (2011). Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913–1920. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-60344-281-7.

- Stillion Southard, Belinda A. (2011). Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913–1920. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-60344-281-7.

- Stevens, Doris (1920). Jailed for Freedom. New York, NY: Liverright Publishing.

- "HOUSE MOVES FOR WOMAN SUFFRAGE; Adopts by 181 to 107 Rule to Create a Committee to Deal with the Subject. DEBATE A HEATED ONE Annoyance of President by Pickets at White House Denounced as "Outlawry."". The New York Times. September 25, 1917.

- Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 45.

- Nardo, Don (1947). The Split History of the Women's Suffrage Movement: A Perspective Flip Book. Stevens Point, WI: Capstone. p. 26.

- Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 45, 47.

- Mickenberg, Julia L. (2014). "Suffragettes and Soviets: American Feminists and the Spector of Revolutionary Russia". Journal of American History. 100 (4): 1041. doi:10.1093/jahist/jau004.

- Skinner, B. F. (2004). "Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten". Public Policy. 415: 6–7.

- "Move Militants from Workhouse". The New York Times. November 25, 1917. p. 6.

- Hunter v. District of Columbia, 47 App. D.C. 406 (D.C. Cir. 1918).

- Collins, Kristin A. (September 18, 2012). "Representing Injustice: Justice as an Icon of Woman Suffrage". SSRN 2459608.

- Phillips, Phillip Edward (2014). Prison Narratives from Boethius to Zena. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 146.

- Kunin, Madeleine (2008). Pearls, Politics, and Power: How Women Can Win and Lead. Chelsea Green. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-933392-92-9.

- Grunwald, Lisa; Stephen J. Adler (2005). Women's letters: America from the Revolutionary War to the present. Dial. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-385-33553-9.

- "Suffrage Voiceless Speeches « Women Suffrage and Beyond". Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- "Iron Jawed Angels". February 15, 2004 – via IMDb.

Sources

- Levin, Carol Simon; Dodyk, Delight Wing (March 2020). "Reclaiming Our Voice" (PDF). Garden State Legacy. Susanna Rich. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

Additional resources

Print book publications

- Basch, F. (2003). Women's Rights and Suffrage In The United States, 1848–1920. Political and Historical Encyclopedia of Women, 443.

- Boyle-Baise, M., & Zevin, J. (2013). FOUR History Mystery: Rediscovering our Past. In Young Citizens of the World (pp. 95–118). Routledge.

- Bozonelis, H. K. (2008). A Look at the Nineteenth Amendment: Women Win the Right to Vote. Enslow Publishers, Inc..

- Cahill, B. (2015). Alice Paul, the National Woman's Party and the Vote: The First Civil Rights Struggle of the 20th Century. McFarland.

- Crocker, R. (2012). Belinda a. Stillion Southard. Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913–1920.(Presidential Rhetoric Series, number 21.) College Station: Texas A&M University Press. 2011

- DuBois, E. C. (1999). Feminism and suffrage: The emergence of an independent women's movement in America, 1848-1869. Cornell University Press.

- Durnford, S. L. (2005). " We shall fight for the things we have always held nearest our hearts": Rhetorical strategies in the US woman suffrage movement.

- Florey, K. (2013). Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study. McFarland.

- Gibson, K. L., & Heyse, A. L. (2011). When the woman suffragettes of the National Woman's Party (NWP) picketed the White House from 1917 to 1919, they carried banners that asked President Woodrow Wilson what he would do to support women's democratic rights and if he would endorse their push for suffrage. Silencing the Opposition: How the US Government Suppressed Freedom of Expression During Major Crises, 151.

- Grant, N. P. C. (1914). Women’s Rights: The Struggle Continues (Doctoral dissertation, SUNY New Paltz).

- Gray, S. (2012). Silent Citizenship in Democratic Theory and Practice: The Problems and Power of Silence in Democracy.

- Gray, S. W. (2014). On the Problems and Power of Silence in Democratic Theory and Practice.

- Horning, N. (2018). The Women’s Movement and the Rise of Feminism. Greenhaven Publishing LLC.

- Nord, Jason. (2015). The Silent Sentinels (Liberty and Justice). Equality Press.

- Marsico, Katie. Women's right to vote : America's suffrage movement. New York : Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, 2011.

- Mountjoy, S., & McNeese, T. (2007). The Women's Rights Movement: Moving Toward Equality. Infobase Publishing.

- Roberts, E. L. (2000). Free Speech, Free Press, Free Society. Unfettered Expression: Freedom in American Intellectual Life.

- Slagell, A. R. (2013). Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman's Party, 1913-1920

- Walton, Mary. (2010). A Women's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. St. Martin's Press.

- Wood, S. V. (1998). Jailed for Freedom: American Women Win the Vote

Journal publications

- Bosmajian, H. A. (1974). The abrogation of the suffragists' first amendment rights. Western Speech, 38(4), 218–232.

- Callaway, H. (1986). Survival and support: Women's forms of political action. In Caught up in Conflict (pp. 214–230). Palgrave, London.

- Carr, J. (2016). Making Noise, Making News: Suffrage Print Culture and US Modernism by Mary Chapman. American Periodicals: A Journal of History & Criticism, 26(1), 108–111.

- Casey, P. F. (1995). Final Battle, The. Tenn. BJ, 31, 20.

- Chapman, M. (2006). “Are Women People?”: Alice Duer Miller's Poetry and Politics. American Literary History, 18(1), 59–85.

- Collins, K. A. (2012). Representing Injustice: Justice as an Icon of Woman Suffrage. Yale JL & Human., 24, 191.

- Costain, A. N., & Costain, W. D. (2017). Protest Events and Direct Action. The Oxford Handbook of US Women's Social Movement Activism, 398.

- Dolton, P. F. (2015). The Alert Collector: Women's Suffrage Movement. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 54(2), 31–36.

- Kelly, K. F. (2011). Performing prison: Dress, modernity, and the radical suffrage body. Fashion Theory, 15(3), 299–321.

- Kenneally, J. J. (2017). " I Want to Go to Jail": The Woman's Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919. Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 45(1), 102.

- McMahon, L. (2016). A Woman's Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(1), 243–245.

- Neuman, J. (2017). The Faux Debate in North American Suffrage History. Women's History Review, 26(6), 1013–1020.

- Noble, G. (2012). The rise and fall of the Equal Rights Amendment. History Review, (72), 30.

- Palczewski, C. H. (2016). The 1919 Prison Special: Constituting white women's citizenship. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 102(2), 107–132.

- Southard, B. A. S. (2007). Militancy, power, and identity: The Silent Sentinels as women fighting for political voice. Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 399–417.

- Stillion Southard, B. A. (2008). The National Woman's Party's Militant Campaign for Woman Suffrage: Asserting Citizenship Rights through Political Mimesis (Doctoral dissertation)

- Ware, S. (2012). The Book I Couldn't Write: Alice Paul and the Challenge of Feminist Biography. Journal of Women's History, 24(2), 13–36.

- Ziebarth, M. (1971). MHS Collections: Woman's Rights Movement. Minnesota History, 42(6), 225–230.

Newspapers

Websites

- Becoming a Detective: Historical Case File #3—Silent Sentinels

- Bryn Mawr on the Picket Line Bryn Mawr on the Picket Lines - The Radicals and Activists]

- Historical Overview of the National Womans Party | Articles and Essays | Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party | Digital Collections | Library of Congress Historical Overview of the National Woman's Party]

- 100 Years Ago, A Different March For Women's Rights]

- Picketing and Protest: Testing the First Amendment]

- Suffrage Voiceless Speeches « Women Suffrage and Beyond Suffrage Voiceless Speeches]

- The Silent Sentinels (Boundary Stones)

- 1917 Suite | Silent Sentinels and the Night of Terror | Blackbird v17n1 | #gallery Silent Sentinels and the Night of Terror]

Videos and multimedia

- This footage from 1913 show Women's Suffrage Parade March Footage from 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade March]

- Silent Sentinel "Silent Sentinel" (2017) Video]

- Clio - Welcome "Silent Sentinels Picket for Women's Suffrage" (1917-1919) Videos]

- About this Collection | Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party | Digital Collections | Library of Congress Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party]

.jpg.webp)