1921 Upper Silesia plebiscite

The Upper Silesia plebiscite was a plebiscite mandated by the Versailles Treaty and carried out on 20 March 1921 to determine ownership of the province of Upper Silesia between Weimar Germany and Poland.[1] The region was ethnically mixed with both Germans and Poles; according to prewar statistics, ethnic Poles formed 60 percent of the population.[2] Under the previous rule by the German Empire, Poles claimed they had faced discrimination, making them effectively second class citizens.[3][4][5] The period of the plebiscite campaign and inter-Allied occupation was marked by violence. There were three Polish uprisings, and German volunteer paramilitary units came to the region as well.

| Outcome | Upper Silesia is divided. East Upper Silesia goes to Poland. West Upper Silesia goes to Germany. | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Pink = Germany

Green = Poland

Lilac = Czechoslovakia (including, without plebiscite, Hlučín)

Pale green = to Poland following plebiscite

Orange = remaining in Germany following plebiscite

The area was policed by French, British, and Italian troops, and overseen by an Inter-Allied Commission. The Allies planned a partition of the region, but a Polish insurgency took control of over half the area. The Germans responded with volunteer paramilitary units from all over Germany, which fought the Polish units. In the end, after renewed Allied military intervention, the final position of the opposing forces became, roughly, the new border. The decision was handed over to the League of Nations, which confirmed this border, and Poland received roughly one third of the plebiscite zone by area, including the greater part of the industrial region.[6]

After the referendum, on 20 October 1921, a conference of ambassadors in Paris decided to divide the region. Consequently, the German-Polish Accord on East Silesia (Geneva Convention), a minority treaty, was concluded on 15 May 1922 which dealt with the constitutional and legal future of Upper Silesia that had partly become Polish territory.

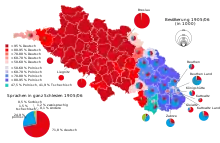

Ethnolinguistic structure before the plebiscite

The earliest exact census figures on ethnolinguistic or national structure (Nationalverschiedenheit) of the Prussian part of Upper Silesia, come from 1819. Polish immigration from Galicia, Congress Poland and Prussian provinces into Upper Silesia during the 19th century was a major factor in their increasing numbers. The last Prussian general census figures available are from 1910 (if not including the 1911 census of school children - Sprachzählung unter den Schulkindern - which revealed a higher percent of Polish-speakers among school children than the 1910 census among the general populace). Figures (Table 1.) show that large demographic changes took place between 1819 and 1910, with the region's total population quadrupling, the percent of Germans increasing significantly, while Polish-speakers maintained their steady increasing numbers. Also the total land area in which Polish was spoken, as well as the land area in which it was spoken, declined between 1790 and 1890.[7] Polish authors before 1918 estimated the number of Poles in Prussian Upper Silesia as slightly higher than according to official German censuses.[8]

The three western districts of Falkenberg (Niemodlin), Grottkau (Grodków) and Neisse (Nysa), though part of Regierungsbezirk Oppeln, were not included in the plebiscite area, as they were almost entirely populated by Germans.

| Table 1. Numbers of Polish, German and other inhabitants (Regierungsbezirk Oppeln)[9][10][11] | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1819 | 1828 | 1831 | 1834 | 1837 | 1840 | 1843 | 1846 | 1852 | 1855 | 1858 | 1861 | 1867 | 1890 | 1900 | 1905 | 1910 |

| Polish | 377,100

(67.2%) |

418,837

(61.1%) |

443,084

(62.0%) |

468,691

(62.6%) |

495,362

(62.1%) |

525,395

(58.6%) |

540,402

(58.1%) |

568,582

(58.1%) |

584,293

(58.6%) |

590,248

(58.7%) |

612,849

(57.3%) |

665,865

(59.1%) |

742,153

(59.8%) |

918,728 (58.2%) | 1,048,230 (56.1%) | 1,158,805 (57.0%) | Census, monolingual Polish: 1,169,340 (53.0%)[12]

or up to 1,560,000 together with bilinguals[8] |

| German | 162,600

(29.0%) |

255,483

(37.3%) |

257,852

(36.1%) |

266,399

(35.6%) |

290,168

(36.3%) |

330,099

(36.8%) |

348,094

(37.4%) |

364,175

(37.2%) |

363,990

(36.5%) |

366,562

(36.5%) |

406,950

(38.1%) |

409,218

(36.3%) |

457,545

(36.8%) |

566,523 (35.9%) | 684,397 (36.6%) | 757,200 (37.2%) | 884,045 (40.0%) |

| Other | 21,503

(3.8%) |

10,904

(1.6%) |

13,254

(1.9%) |

13,120

(1.8%) |

12,679

(1.6%) |

41,570

(4.6%) |

42,292

(4.5%) |

45,736

(4.7%) |

49,445

(4.9%) |

48,270

(4.8%) |

49,037

(4.6%) |

51,187

(4.6%) |

41,611

(3.4%) |

92,480

(5.9%) |

135,519

(7.3%) |

117,651

(5.8%) |

Total population: 2,207,981 |

The plebiscite

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

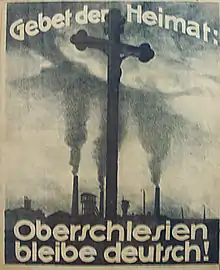

The Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I placed some formerly German territory in neighboring countries, some of which had not existed at the beginning of the war. In the case of the new Polish state, the Treaty of Versailles established some 54,000 square kilometers of formerly German territory as part of newly independent Poland. Many of these areas were ethnically mixed. In three of these ethnically mixed areas on the new German-Polish border, however, the Allied leaders provided for border plebiscites or referendums. The areas would be occupied by Allied forces and governed in some degree by Allied commissions. The most significant of these plebiscites was the one in Upper Silesia, since the region was a principal industrial center. The most important economic asset was the enormous coal-mining industry and its ancillary businesses, but the area yielded iron, zinc, and lead as well. The "Industrial Triangle" on the eastern side of the plebiscite zone—between the cities of Beuthen (Bytom), Kattowitz (Katowice), and Gleiwitz (Gliwice) was the heart of this large industrial complex. The Upper Silesia plebiscite was therefore a plebiscite for self-determination of Upper Silesia required by the Treaty of Versailles. Both Germany and Poland valued this region not only for reasons of national feeling, but for its economic importance as well.

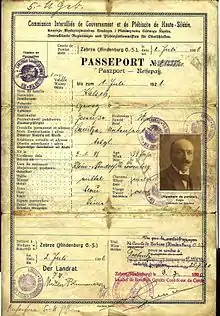

The area was occupied by British, French, and Italian forces, and an Interallied Committee headed by a French general, Henri Le Rond. The plebiscite was set for 20 March 1921. Both Poles and Germans were allowed to organize campaigns. Each side developed secret paramilitary forces—both financed from the opposing capitals, Warsaw and Berlin. The major figure of the campaign was Wojciech Korfanty, a pro-Polish politician. The Germans complained to the still offcial Prussian Courts that Germans were being diared while a blind eye was turned to Polish militias, and intimidation of Germans in smaller Polish controlled towns and villages. The plebiscite area was largely cut off from normal contact with Germany. Upper Silesia was not represented in the Reichtstag, and German citizens needed visas to enter the plebiscite area. When the Second Silesian Uprising broke out, the British delegation blamed the French delegations pro-Polish bias for the ease with which the uprising had spread.[13]

The Poles carried out two uprisings during the campaign, in August 1919 and August 1920. The Allies restored order in each case, but the Polish insurrectionists clashed with German "volunteers," the Freikorps.[14]

A feature of the plebiscite campaign was the growing prominence of a strong autonomist movement, the most visible branch of which was the Bund der Oberschlesier/Związek Górnoślązaków. This organization attempted to gain promises of autonomy from both states and possible future independence for Upper Silesia.[15]

There were 1,186,758 votes cast in an area inhabited by 2,073,663 people.[16] It resulted in 717,122 votes being cast for Germany and 483,514 for Poland. The towns and most of the villages in the plebiscite territory gave German majorities. However, the districts of Pless (Pszczyna) and Rybnik in the southeast, as well as Tarnowitz (Tarnowskie Góry) in the east and Tost-Gleiwitz (Gliwice) in the interior showed considerable Polish majorities, while in Lublinitz (Lubliniec) and Groß Strehlitz (Strzelce Opolskie) the votes cast on either side were practically equal. All the districts of the industrial zone in a narrower sense - Beuthen (Bytom), Hindenburg (Zabrze), Kattowitz (Katowice), and Königshütte (Chorzów) - had slight German majorities, though in Beuthen and Kattowitz this was due entirely to the town vote (four-fifths in Kattowitz compared to an overall 60%).[17] Many country communes of Upper Silesia had given Polish majorities. Overall, however, the Germans won the vote by a measure of 59.4% to 40.6%.[18] The Interallied Commission deliberated, but the British proposed a more easterly border than the French, which would have given much less of the Industrial Triangle to Poland.

In late April 1921, when pro-Polish forces began to fear that the region would be partitioned according to the British plan, elements on the Polish side announced a popular uprising. Korfanty was the leading figure of the uprising, but he had much support in Upper Silesia as well as support from the Polish government in Warsaw. Korfanty called for a popular armed uprising whose aim was to maximize the territory Poland would receive in the partition. German volunteers rushed to meet this uprising, and fighting on a large scale took place in the late spring and early summer of 1921. Germanophone spokesmen and German officials complained that the French units of the Upper Silesian army of occupation were favoring the insurrection by refusing to put down their violent activities or restore order.

Twelve days after the start of the uprising, Wojciech Korfanty offered to take his Upper Silesian forces behind a line of demarcation, on condition that the released territory would not be occupied by German forces, but by Allied troops. On 1 July 1921 British troops returned to Upper Silesia to help French forces occupy this area. Simultaneously with these events, the Interallied Commission pronounced a general amnesty for the illegal actions committed during the recent violence, with the exception of acts of revenge and cruelty. The German defense force was finally withdrawn.

Because the Allied Supreme Council was unable to come to an agreement on the partition of the Upper Silesian territory on the basis of the confusing plebiscite results, a solution was found by turning the question over to the Council of the League of Nations. Agreements between the Germans and Poles in Upper Silesia and appeals issued by both sides, as well as the dispatch of six battalions of Allied troops and the disbandment of the local guards, contributed markedly to the pacification of the district. On the basis of the reports of a League commission and those of its experts, the Council awarded the greater part of the Upper Silesian industrial district to Poland. Poland obtained almost exactly half of the 1,950,000 inhabitants, viz., 965,000, but not quite a third of the territory, i.e., only 3,214.26 km2 (1,255 mi2) out of 10,950.89 km2 (4,265 mi2) but more than 80% of the heavy industry of the region.[19]

The German and Polish governments, under a League of Nations recommendation, agreed to enforce protections of minority interests that would last for 15 years. Special measures were threatened in case either of the two states should refuse to participate in the drawing up of such regulations, or to accept them subsequently. In the event, the German minority remaining on the Polish side of the border suffered considerable discrimination in the subsequent decades.[20]

The Polish Government, convinced by the economic and political power of the region and by the autonomist movement of the plebiscite campaign, decided to give Upper Silesia considerable autonomy with a Silesian Parliament as a constituency and the Silesian Voivodship Council as the executive body. On the German side the new Prussian province of Upper Silesia (Oberschlesien) with regional government in Oppeln was formed, likewise with special autonomy.

Results

| County | population (1919) | registered voters | turnout | votes for Germany | % | votes for Poland | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beuthen (Bytom), town [21] | 71,187 | 42,990 | 39,991 | 29,890 | 74.7% | 10,101 | 25.3% |

| Beuthen (Bytom), district [21] | 213,790 | 109,749 | 106,698 | 43,677 | 40.9% | 63,021 | 59.1% |

| Cosel (Koźle), district [22] | 79,973 | 51,364 | 50,100 | 37,651 | 75.2% | 12,449 | 24.8% |

| Gleiwitz (Gliwice), town [23] | 69,028 | 41,949 | 40,587 | 32,029 | 78.9% | 8,558 | 21.1% |

| Groß Strehlitz (Strzelce Opolskie), district [24] | 76,502 | 46,528 | 45,461 | 22,415 | 49.3% | 23,046 | 50.7% |

| Hindenburg (Zabrze), district [25] | 167,632 | 90,793 | 88,480 | 45,219 | 51.1% | 43,261 | 48.9% |

| Kattowitz (Katowice), town [26] | 45,422 | 28,531 | 26,674 | 22,774 | 85.4% | 3,900 | 14.6% |

| Kattowitz (Katowice), district [26] | 227,657 | 122,342 | 119,011 | 52,892 | 44.4% | 66,119 | 55.6% |

| Königshütte (Chorzów), town [27] | 74,811 | 44,052 | 42,628 | 31,864 | 74.7% | 10,764 | 25.3% |

| Kreuzburg (Kluczbork), district [28] | 52,558 | 40,602 | 39,627 | 37,975 | 95.8% | 1,652 | 4.2% |

| Leobschütz (Głubczyce), district [29] | 78,247 | 66,697 | 65,387 | 65,128 | 99.6% | 259 | 0.4% |

| Lublinitz (Lubliniec), district [30] | 55,380 | 29,991 | 29,132 | 15,453 | 53.0% | 13,679 | 47.0% |

| Namslau (Namysłów), district [31] | 5,659 | 5,606 | 5,481 | 5,348 | 97.6% | 133 | 2.4% |

| Neustadt (Prudnik), district [32] | 51,287 | 36,941 | 36,093 | 31,825 | 88.2% | 4,268 | 11.8% |

| Oppeln (Opole), town [33] | 35,483 | 22,930 | 21,914 | 20,816 | 95.0% | 1,098 | 5.0% |

| Oppeln (Opole), district [33] | 123,165 | 82,715 | 80,896 | 56,170 | 69.4% | 24,726 | 30.6% |

| Pleß (Pszczyna), district [34] | 141,828 | 73,923 | 72,053 | 18,675 | 25.9% | 53,378 | 74.1% |

| Ratibor (Racibórz), town [35] | 36,994 | 25,336 | 24,518 | 22,291 | 90.9% | 2,227 | 9.1% |

| Ratibor (Racibórz), district [35] | 78,238 | 45,900 | 44,867 | 26,349 | 58.7% | 18,518 | 41.3% |

| Rosenberg (Olesno), district [36] | 54,962 | 35,976 | 35,007 | 23,857 | 68.1% | 11,150 | 31.9% |

| Rybnik, district [37] | 160,836 | 82,350 | 80,266 | 27,919 | 34.8% | 52,347 | 65.2% |

| Tarnowitz (Tarnowskie Góry), district [38] | 86,563 | 45,561 | 44,591 | 17,078 | 38.3% | 27,513 | 61.7% |

| Tost-Gleiwitz (Gliwice), district [23] | 86,461 | 48,153 | 47,296 | 20,098 | 42.5% | 27,198 | 57.5% |

| Total [39] | 2,073,663 | 1,220,979 | 1,186,758 | 707,393 | 59.6% | 479,365 | 40.4% |

| Total without Namslau district [18] | 2,068,004 | 1,215,373 | 1,181,277 | 702,045 | 59.4% | 479,232 | 40.6% |

According to Article 88 of the Treaty of Versailles all inhabitants of the plebiscite district older than 20 years of age and those who had "been expelled by the German authorities and have not retained their domicile there" were entitled to return to vote.

This stipulation of the Treaty of Versailles allowed the participation of thousands of Upper Silesian migrant workers from western Germany (Ruhrpolen). Hugo Service regards the transport of these eligible voters to Silesia, organized by German authorities, "a cynical act aimed at boosting the German vote", in his opinion it was one of the reasons for the overall result. As Service writes, despite the fact that almost 60% of Upper Silesians voted for their region to remain part of Germany it would be dubious to claim that most of them were ethnically German or regarded themselves as Germans. Voting for Germany in the 1921 vote and regarding oneself as German were two different things. People had diverse, often very pragmatic reasons for voting for Germany, which usually had little to do with a person regarding him or herself as having a German ethnonational identity.[40][41]

According to Robert Machray, 192,408 of all plebiscite voters were migrants, making up 16% of the total electorate. Among them, 94.7% voted for Germany.[42] There were cases of votes being cast in the name of already deceased persons who died outside of Upper Silesia, and since their deaths were registered" in comparatively inaccessible German registration departments in Central Germany", it was often difficult to detect voter fraud.[42] Additionally, "the general conditions in which the plebiscite was held by no means created an atmosphere for a free and independent vote" - the administration was staffed by ethnic Germans only, and no Polish schools were allowed, limiting Polish cultural life to churches and private organisations.[42] The Polish population of Silesia overwhelmingly consisted of poor workers and small farmers, who owned no real property and were highly dependent on the German authorities to provide appropriate instrastructure. All offices and every industry was controlled by the German population, who exerted an overwhelming pressure on Poles to vote for Germany, and they "frequently exceeded their lawful powers and supported many forms of anti-Polish activities".[42]

Demobilised German officers joined the Freikorps and terrorised the Polish population,; Machray states that "Upper Silesia was the scene of incessant confusion, sanguinary struggles with armed German attacks on Polish meetings and on the terrorized and defenceless Polish population, especially in the rural areas."[42] Emil Julius Gumbel investigated and condemned the cases of widespread intimidation and murders by Freikorps and Selbstschutz divisions, remarking: “a denunciation, a suspicion without foundation under the given circumstances, was sufficient. The man concerned is fetched from his lodgings and instantly shot ... all this only because the man was a Pole or was considered a Pole and worked for union with Poland.”[42][43] Machray establishes that many Poles were either prevented from voting or were intimidated into voting for Germany, noting that in provinces such as Kozle and Olesno, a minority of voters voted for Poland, despite the fact that these areas were overwhelmingly Polish according to the 1910 census, with Poles making up 75% of the Kozle and 80.7% of the Olesno provinces, respectively. Machray concludes that given the aggressive anti-Polish campaign conducted by local authorities and German volunteers, "the results were far from being an objective reflection of the true desires of the oppressed people".[42] The constant ethnic tensions and attacks on Polish voters resulted in the Silesian Uprisings.[44]

Comparison of district demographics with voting behavior

The following table compares the percentage of German speakers (excluding bilinguals) as reported in the 1910 census in each district, with the pro-German vote share registered in the respective district. In almost all districts, the percentage of pro-German votes exceeded the percentage of those who identified as German by almost 25% on average, suggesting that many non-Germans voted in favour of Germany.[45] The historian Richard Blanke explained this disparity in the number of German speakers versus the German vote by saying "Some [Poles] became German altogether (that is, "objectively"), but most continued to speak Polish while identifying politically with Germany (that is, they became "subjectively" German). In one presumably typical Upper Silesian village analyzed in detail by the pioneering sociologist Jozef Chalasinski, fewer than 10 percent of the inhabitants were German by native language, yet 33 percent of the newspapers sold there were German, and 34 percent of the village's vote in the 1921 plebiscite went to Germany. When Chalasinski conducted this study in the early 1930s, after this community had been part of Poland for ten years, many local "Poles" continued to exhibit signs of a subjective German national consciousness."[46]

| District | % of German Population[45] | % of votes for Germany |

|---|---|---|

| Beuthen (Bytom), town | 60.7% | 74.7% |

| Beuthen (Bytom), district | 30.3% | 40.9% |

| Cosel (Koźle), district | 21.7% | 75.2% |

| Gleiwitz (Gliwice), town | 74.0% | 78.9% |

| Groß Strehlitz (Strzelce Opolskie), district | 17.2% | 49.3% |

| Hindenburg (Zabrze), district | 40.0% | 51.1% |

| Kattowitz (Katowice), town | 85.4% | 85.4% |

| Kattowitz (Katowice), district | 30.3% | 44.4% |

| Königshütte (Chorzów), town | 54.1% | 74.7% |

| Kreuzburg (Kluczbork), district | 46.9% | 95.8% |

| Leobschütz (Głubczyce), district | 84.6% | 99.6% |

| Lublinitz (Lubliniec), district | 14.7% | 53.0% |

| Namslau (Namysłów), district1 | 72.5% | 97.6% |

| Neustadt (Prudnik), district2 | 52.8% | 88.2% |

| Oppeln (Opole), town | 80.0% | 95.0% |

| Oppeln (Opole), district | 20.1% | 69.4% |

| Pleß (Pszczyna), district | 13.4% | 25.9% |

| Ratibor (Racibórz), town | 59.6% | 90.9% |

| Ratibor (Racibórz), district3 | 11.2% | 58.7% |

| Rosenberg (Olesno), district | 16.4% | 68.1% |

| Rybnik, district | 18.9% | 34.8% |

| Tarnowitz (Tarnowskie Góry), district | 27.0% | 38.3% |

| Tost-Gleiwitz (Gliwice), district | 20.4% | 42.5% |

| Total | 35.7% | 59.6% |

| Total without Namslau district | 35.1% | 59.4% |

The above-mentioned population percentages refer to the entire area of the respective districts, however in a few cases, only parts of a district were included in the plebiscite area:

1 Only a small part of the Namslau district was part of the plebiscite area; 1905 census data was used for this district

2 The predominantly German south-western part of the Neustadt district (including the town of Neustadt) was not part of the plebiscite area

3 The southern part of the Ratibor district (Hlučín Region) was ceded to Czechoslovakia in 1919 and hence was not included in the plebiscite area

Settlements that voted to secede for Poland

In the 1921 plebiscite, 40.6% of eligible voters decided to secede from Germany and become Polish citizens.[18] In total over seven hundred towns and villages voted in majority to secede from Germany and become part of Poland, especially in the rural districts of Pszczyna,[34] Rybnik,[37] Tarnowskie Góry,[38] Toszek-Gliwice,[23] Strzelce Opolskie,[24] Bytom,[21] Katowice,[26] Lubliniec,[30] Zabrze,[25] Racibórz,[35] Olesno,[36] Koźle[22] and Opole.[33]

Division of the region after the plebiscite

| Division of: | Area in 1910 in km2 | Share of territory | Population in 1910 | After WW1 part of: | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Silesia | 27,105 km2 [47] | 100% | 3,017,981 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 526 km2 [48][49] | 2% | 1% | Poznań Voivodeship | [Note 1] |

| to Germany | 26,579 km2 | 98% | 99% | Province of Lower Silesia | |

| Upper Silesia | 13,230 km2 [47] | 100% | 2,207,981 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 3,225 km2 [51] | 25% | 41% [51] | Silesian Voivodeship | [Note 2] |

| to Czechoslovakia | 325 km2 [51] | 2% | 2% [51] | Hlučín Region | |

| to Germany | 9,680 km2 [51] | 73% | 57% [51] | Province of Upper Silesia |

See also

Notes

- After World War I Poland received a small part of historical Lower Silesia, with majority ethnic Polish population as of year 1918. That area included parts of counties Syców (German: Polnisch Wartenberg), Namysłów, Góra and Milicz. In total around 526 square kilometers with around 30 thousand[48][51] inhabitants, including the city of Rychtal. Too small to form its own voivodeship, the area was incorporated to Poznań Voivodeship (former Province of Posen).

- Interwar Silesian Voivodeship was formed from Prussian East Upper Silesia (area 3,225 km2) and Polish part of Austrian Cieszyn Silesia (1,010 km2), in total 4,235 km2. After the annexation of Trans-Olza from Czechoslovakia in 1938, it increased to 5,122 km2.[52] Silesian Voivodeship's capital was Katowice.

References

- F. Gregory Campbell, "The Struggle for Upper Silesia, 1919-1922." Journal of Modern History 42.3 (1970): 361-385. online Archived 2022-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- T. Hunt Tooley, "National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the eastern border", University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p. 140

- Racisms Made in Germany edited by Wulf D. Hund, Wulf Dietmar Hund, Christian Koller, Moshe Zimmermann LIT Verlag Münster 2011 page 20, 21

- The Ideology of Kokugo: Nationalizing Language in Modern Japan Lee Yeounsuk page 161 University of Hawaii Press 2009

- The Immigrant Threat: The Integration of Old and New Migrants in Western Europe since 1850 (Studies of World Migrations) Leo Lucassen page 61 University of Illinois Press page 2005

- T. Hunt Tooley, "German political violence and the border plebiscite in Upper Silesia, 1919–1921." Central European History 21.1 (1988): 56-98.

- Joseph Partsch (1896). "Die Sprachgrenze 1790 und 1890". Schlesien: eine Landeskunde für das deutsche Volk. T. 1., Das ganze Land (in German). Breslau: Verlag Ferdinand Hirt. pp. 364–367.

- Kozicki, Stanislas (1918). The Poles under Prussian rule. Toronto: London, Polish Press Bur. pp. 2–3.

- Georg Hassel (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt (in German). Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 34.

Nationalverschiedenheit 1819: Polen - 377,100; Deutsche - 162,600; Mährer - 12,000; Juden - 8,000; Tschechen - 1,600; Gesamtbevölkerung: 561,203

- Paul Weber (1913). Die Polen in Oberschlesien: eine statistische Untersuchung (in German). Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung von Julius Springer.

- Kalisch, Johannes; Bochinski, Hans (1958). "Stosunki narodowościowe na Śląsku w świetle relacji pruskich urzędników z roku 1882" (PDF). Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka. Leipzig. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-01.

- Paul Weber (1913). Die Polen in Oberschlesien: eine statistische Untersuchung (in German). Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung von Julius Springer. p. 27.

- Blanke, Richard (7 July 2014). Orphans of Versailles. The Germans in Western Poland 1918-1939. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8131-5633-0.

- T. Hunt Tooley, "German Political Violence and the Border Plebiscite in Upper Silesia, 1919-1921," Central European History 21 (March 1988): 56-98.

- Günter Doose, Die separatistische Bewegung in Oberschlesien nach dem ersten Weltkrieg. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1987

- herder-institut.de: (in German, French, and Polish) Results of the plebiscites in three Prussian districts conducted between July 1920 and March 1921, according to Polish sources. "Rocznik statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej" (PDF). Główny Urząd Statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej GUS, Annual (Main Statistical Office of the Republic of Poland). 1920. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-22. Retrieved 2012-06-08. - Also in HTML

- Urban, Thomas (2003). Polen (2 ed.). C.H.Beck. p. 40. ISBN 3-406-44793-7. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- Volksabstimmungen in Oberschlesien 1920-1922 (gonschior.de)

- Karl Junge, 1922, "Foreign and colonial history: Germany and Austria (Ch.III), Germany," in The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad, for the Year 1921 (M. Epstein, Ed.), pp. 177-186, esp. 179f, New Yprk, NY, USA: Longmans, Green, and Co., see , accessed 6 July 2015.

- Richard Blanke, Orphans of Versailles: The Germans in Western Poland, 1918-1939. Lexington, KY: The University of Kentucky Press, 1993.

- "Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Beuthen". Archived from the original on 2015-04-05. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Cosel Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Gleiwitz und Tost Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Groß Strehlitz Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Hindenburg". Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Kattowitz Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Königshütte". Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- "Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Kreuzburg". Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Leobschütz

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Lublinitz Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Namslau". Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Neustadt Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Oppeln Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Pless Archived 2015-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Ratibor Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Rosenberg Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Rybnik Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Die Volksabstimmung in Oberschlesien 1921: Tarnowitz Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Herder Institut (in German)

- Service, Hugo (2013). Germans to Poles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67148-5.

- Tooley, T. Hunt. National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918-1922 University of Nebraska Press 1997, ISBN 978-0803244290, p. 234-252

- Machray, Robert (1945). The Problem of Upper Silesia (PDF). Michigan: G. Allen & Unwin Limited. pp. 79–83.

- Gumbel, Emil Julius (1929). Verräter verfallen der Feme! (in German). Berlin. p. 156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Peter Leśniewski (2001) The 1919 insurrection in upper Silesia, Civil Wars, 4:1, 22-48, DOI: 10.1080/13698240108402462

- Belzyt, Leszek (1998). Sprachliche Minderheiten im preussischen Staat: 1815 - 1914 ; die preußische Sprachenstatistik in Bearbeitung und Kommentar. Marburg: Herder-Inst. ISBN 978-3-87969-267-5.

- Blanke, Richard (7 July 2014). Orphans of Versailles. The Germans in Western Poland 1918-1939. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8131-5633-0.

- "Gemeindeverzeichnis Deutschland: Schlesien".

- "Rocznik statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1920/21". Rocznik Statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (in Polish and French). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. I: 56–62. 1921.

- "Schlesien: Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert". OME-Lexikon - Universität Oldenburg.

- Sperling, Gotthard Hermann (1932). "Aus Niederschlesiens Ostmark" (PDF). Opolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa.

- Weinfeld, Ignacy (1925). Tablice statystyczne Polski: wydanie za rok 1924 [Poland's statistical tables: edition for year 1924]. Warsaw: Instytut Wydawniczy "Bibljoteka Polska". p. 2.

- Mały Rocznik Statystyczny [Little Statistical Yearbook] 1939 (PDF). Warsaw: GUS. 1939. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

Further reading

- Campbell, F. Gregory Campbell, "The Struggle for Upper Silesia, 1919-1922." Journal of Modern History 42.3 (1970): 361–385. online Archived 2022-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Rodriguez, Allison Ann. "Silesia at the Crossroads: Defining Germans and Poles in Upper Silesia During the First World War and Plebiscite Period" (PhD Diss. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2020) online.

- Tooley, T. Hunt. "German political violence and the border plebiscite in Upper Silesia, 1919–1921." Central European History 21.1 (1988): 56–98.

- Tooley, T. Hunt. National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918-1922. (University of Nebraska Press, 1997).

- Walters, F. P. A History of the League of Nations (Oxford University Press, 1952). online

- Wilson, T. K. Frontiers of Violence: Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia 1918-1922 (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Czesław Madajczyk, Tadeusz Jędruszczak, Plebiscyt i trzecie powstanie śląskie ("Plebiscite and Third Silesian Uprising") [in:] Historia Polski ("History of Poland"), Vol.IV, part 1, PAN, Warszawa 1984 ISBN 83-01-03865-9

- Kazimierz Popiołek, Historia Śląska od pradziejów do 1945 roku ("History of Poland since prehistory until 1945"), Śląski Inst. Naukowy (Silesian Science Institute) 1984 ISBN 83-216-0151-0

External links

- Wojciech Korfanty's proclamation after plebiscite

- Exact plebiscite results - according to villages and districts (in German)

- 1920 map showing German territory's changes, including marked area for the Upper Silesia plebiscite

- Map of interwar Poland; shows plebiscite areas

- Map of interwar Poland; shows plebiscite areas Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine (in color, Polish)