Simion Movilă

Simion Movilă (after 1559[8][9] – 14 September 1607),[7] a boyar of the Movilești family, was twice Prince of Wallachia (November 1600 – June 1601; October 1601 – July 1602) and Prince of Moldavia from July 1606 until his death.[6]

| Simion Movilă | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prince of Wallachia (1st reign) | |

| Reign | November 1600 – June 1601[1] |

| Predecessor | Michael the Brave[2] |

| Successor | Radu Mihnea[3] |

| Prince of Wallachia (2nd reign) | |

| Reign | October 1601 – August or July 1602[4][1] |

| Predecessor | Radu Mihnea[3] |

| Successor | Radu Șerban[5] |

| Prince of Moldavia | |

| Reign | July 1606[6] – 14 September 1607[7] |

| Predecessor | Ieremia Movilă[6] |

| Successor | Mihail Movilă[6] |

| Born | After 1559[8][9] |

| Died | 14 September 1607[7] |

| Spouse | Marghita[7] |

| Issue | Peter Mogila[10] Mihail Movilă Gabriel Movilă[11] |

| House | Movilești family |

| Father | Ioan Movilă[12] |

| Mother | Maria Movilă[13] |

| Religion | Orthodox[14] |

Family

He was the grandson of Petru Rareș,[15] younger brother of Ieremia Movilă,[9][13] and father of Peter Mogila, who became the Metropolitan of Kiev, Halych and All-Rus'[lower-alpha 1] from 1633 until his death, and later was canonized as a saint in the Russian, Romanian and Polish Orthodox Churches.[10]

Biography

In the early 1580s, Simion, along with his brothers, built Sucevița Monastery.[14][18][19]

In October 1600,[1] he was put on the throne of Wallachia by Polish forces.[20]

In August 1602, Simion was defeated by Radu Șerban and forced into exile to Moldavia.[4]

After the death of his brother Ieremia in July 1606, Simion gained the Moldavian throne.[6] By making rich gifts, Simion managed to be recognized by the sultan. While he was ruler of Moldavia, he had hostile relations with the Poles.

Death

He died on September 14, 1607, after a reign of only a year and a few months. His death was suspected to be the result of poisoning,[21] which only further inflamed tensions around succession.[7][22] This eventually spiralled into war, which was eventually won by his son Mihail after Polish support.[6]

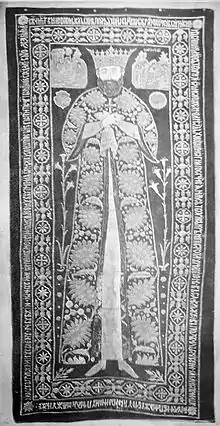

Simion was buried at the Sucevița Monastery.[23]

References

- von Herrmann, George Michael Gottlieb (2010). Das alte Kronstadt: eine siebenbürgische Stadt- und Landesgeschichte bis 1800, Volume 1 (in German). p. 127. ISBN 9783412204396.

- Djuvar (2016, p. 193)

- Panaite, Viorel (29 July 2019). Ottoman Law of War and Peace: The Ottoman Empire and Its Tribute-Payers from the North of the Danube. Second Revised Edition. p. 402. ISBN 9789004411104.

- Alexandru Ioan Cuza university (2009, p. 218)

- Kolodziejczyk (2011, p. 116)

- Kolodziejczyk (2011, p. 837)

- Alexandru Ioan Cuza university (2009, p. 221)

- Göbl (1907, p. 253)

- Wasiucionek, Michał. Politics and Watermelons | Cross-Border Political Networks in the Polish-Moldavian-Ottoman Context in the Seventeenth Century (PDF) (Thesis).

- "The Orthodox Faith - Volume III - Church History - Seventeenth Century - Saint Peter Mogila". www.oca.org. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Suciu (1980, p. 165)

- Miclescu-Prăjescu (1971, p. 222)

- Miclescu-Prăjescu (1971, p. 214)

- "Tourism - Sucevita Monastery". 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Miclescu-Prăjescu (1971, p. 231)

- "The Ecumenical Throne and the Church of Ukraine". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. 28 September 2018. p. 4. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

The Metropolis of Russia is recorded in the ancient official charters of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, such as for instance in the Formulation of Leo the Wise (11th century),1 as the sixtieth eparchy of the Ecumenical Throne. Originally, it was united under the name "Kyiv and all Russia," with Kyiv as its see.

- "Kyiv metropoly". Retrieved 13 November 2021.

The title 'metropolitan of Kyiv, Halych, and Little Russia' was restored in 1743

- Sheehan, Sean; Nevins, Debbie (15 July 2015) [1994]. Romania. Cavendish Square Publishing LLC. p. 136. ISBN 9781502603371.

- Scarce, Jennifer M. (8 April 2014) [1987]. Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East. Taylor & Francis. p. 105. ISBN 9781136783852.

- Boia, Lucian; Brown, James Christian (2001) [1997]. History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. p. 274. ISBN 9789639116962.

- Wasiucionek, Michal (27 June 2019). The Ottomans and Eastern Europe: Borders and Political Patronage in the Early Modern World. p. 173?. ISBN 9781788318587.

[Simion] died suddenly in September 1607, and many suspected that he was poisoned by Elizabeta to pave the way to the throne for his thirteen-year-old son.

- "Mohyla, Petro". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Ogden, Alan, ed. (12 January 2021) [2002]. Revelations of Byzantium:The Monasteries and Painted Churches of Northern Moldavia. Histria Books. p. 226. ISBN 9781592110681.

Bibliography

- Alexandru Ioan Cuza university (2009). Medieval and Early Modern for Central and Eastern Europe. Al I Cuza University Press.

- Djuvar, Neagu (28 October 2016). A Brief Illustrated History of Romanians. ISBN 9789735053819.

- Göbl, Carol (1907). Catalogul manuscriptelor românești: întocmit de Ioan Bianu, bibliotecarul Academiei Române, Volume 1 (in Romanian).

- Kolodziejczyk, Dariusz (22 June 2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th-18th Century). A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by Annotated Documents. ISBN 978-9004191907.

- Miclescu-Prăjescu, I. (April 1971). "New Data regarding the Installation of Movilă Princes". The Slavonic and East European Review. Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies. 49 (115): 214–234. JSTOR 4206367. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Suciu, I. D. (1980). Unitatea poporului român: contribuții istorice bănățene (in Romanian). Facla.