Single-grain experiment

The single-grain experiment was an experiment carried out at the University of Wisconsin–Madison from May 1907 to 1911. The experiment tested if cows could survive on a single type of grain. The experiment would lead to the development of modern nutritional science.

History

Foundations

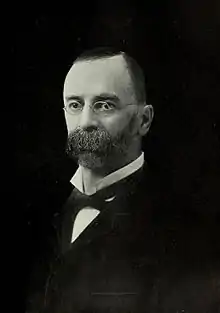

In 1881, agricultural chemist Stephen M. Babcock returned to the United States after earning his doctorate in organic chemistry at the University of Göttingen, Germany to accept a position at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, New York where his first assignment was to determine the proper feed ratios of carbohydrate, fat, and protein from cow feces using chemical analysis. His findings determined that the feces' chemical composition was similar to that of the feed with the only major exception being the ash. These results were tested and retested, and his results were found to be similar to German studies done earlier. This led Babcock to think about what would happen if the cows were fed a single grain (barley, corn, wheat) though that test would not occur for nearly twenty-five years.

Seven years later, Babcock accepted a position at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Agricultural Experiment Station (UWAES) as chair of the Agricultural Chemistry department, and immediately began petitioning Dean of Agriculture William Arnon Henry, then station director, to perform the "single-grain experiment". Henry refused.

Babcock continued pressing Henry to perform the "single-grain experiment", even approaching the UWAES animal husbandry chair J.A. Craig (he refused). When W.L. Carlyle replaced Craig in 1897, Carlyle was more receptive to Babcock's idea. Initially trying a salt experiment with eight dairy cows as a matter of taste preference while eight other cows received no salt. After one of the eight cows that did not receive salt died, Carlyle discontinued the experiment and all the remaining cows were given salt in order to restore their health.

Henry, now Dean of Agriculture in 1901, finally relented and gave Babcock permission to perform the experiment. Carlyle approved the experiment with only two cows. One cow was fed corn while the other was fed rolled oats and straw with hopes the experiment would last one year. Three months into the experiment, the oat-fed cow died, and Carlyle halted the event to save the other cow's life. The results were not published mainly because Babcock did not list how much of each grain the respective cows had consumed.

In 1906, a chemist from the University of Michigan, Edwin B. Hart (1874–1953), was hired by Babcock. Hart previously had worked at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, and had studied physiological chemistry under Albrecht Kossel in Germany. Both worked with George C. Humphrey, who replaced Carlyle as animal husbandry professor, to plan a long-term feeding plan using a chemically-balanced diet of carbohydrates, fat, and protein instead of single plant rations as done in Babcock's earlier experiments. The "single-grain experiment" was thus born in 1907.

The experiment

From May 1907 to 1911, the experiment was carried out with Hart as director, Babcock providing the ideas, and Humphrey overseeing the welfare of the cows during the experiment. Elmer McCollum, an organic chemist from Connecticut, was hired by Hart to analyze the grain rations and the cow feces. The experiment called for four groups of four heifers each during which three groups were raised and two pregnancies were carried through during the experiment. The first group ate only corn (corn stover, corn meal and gluten feed), the second group ate only nutrients from the wheat plant (wheat straw, wheat meal and wheat gluten), the third group ate only nutrients from the oat plant (oat straw and rolled oats),[1] and the last group ate a mixture of the other three.

In 1908, it was shown that the corn-fed animals were the most healthy of the group while the wheat-fed groups were the least healthy. All four groups bred during that year with the corn-fed calves being the healthiest while the wheat and mixed-fed calves were stillborn or later died. Similar results were found in 1909. In 1910, the corn-fed cows had their diets switched to wheat and the non-corn-fed cows were fed corn. This produced unhealthy calves for the formerly corn-fed cows while the remaining cows produced healthy calves. When the 1909 formulas were reintroduced to the respective cows in 1911, the gestation results of 1909 reoccurred in 1911. These results were published in 1911. Similar results had been done in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in 1901, in Poland 1910, and in England in 1906 (though the English results were not published until 1912).

Legacy

"This experiment made it clear that there were marked differences in nutritive values which could not be detected by any chemical means available at the time and that the current scientific bases for formulating rations were seriously inadequate. More important, the experiment led to the conviction that simplified diets must be used for the solution of nutrition problems."[2] The experiment would lead to the development of nutrition as a science. It would also lead to a determination that there were minerals and vitamins in food; that research would continue into the 1930s and 1940s, ending in 1948 with the discovery of Vitamin B12.[3]

References

- Carpenter, Kenneth J. (2003). "A Short History of Nutritional Science Part 2 (1885–1912)." The Journal of Nutrition 133:975-84. April. Accessed October 9, 2006.

- "Nutrition." A Century of Food Science (2000). Institute of Food Technologists: Chicago, pp. 27–28.

- The University of Wisconsin–Madison Dairy Barn building

- Petition from Madison, Wisconsin to National Park Service for University of Wisconsin–Madison Dairy Barn to be named a National Landmark, pp. 21–25.

- University of Wisconsin–Madison Dairy Barn Historical: impact on the "single-grain experiment."

- UW–-Madison Dairy Barn Being Considered as National Treasure

Specific

- Hart, E. B., E. V. McCollum, H. Steenbock, and G. C. Humphrey, Physiological effect on growth and reproduction of rations balanced from restricted sources, Wis. Agr. Expt. Sta. Research Bull. 17, 1911

- Leonard Maynard, Animal Nutrition, First Edition, 1937, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York and London.

- Rickes, E. L. et al. 1948. Science 107:396; Smith, E. L., and L. E. J. Parker. 1948 Biochem. J. 43:viii.