Henry Havelock

Major-General Sir Henry Havelock KCB (5 April 1795 – 24 November 1857) was a British general who is particularly associated with India and his recapture of Cawnpore during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (First War of Independence, Sepoy Mutiny).

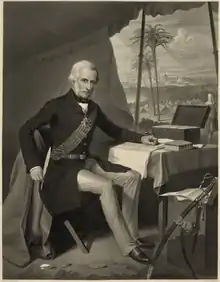

Sir Henry Havelock | |

|---|---|

Henry Havelock, 1865 portrait | |

| Born | 5 April 1795 Bishopwearmouth, Sunderland, England |

| Died | 24 November 1857 (aged 62) Alumbagh, Lucknow, British India |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1815–1857 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Battles/wars | First Anglo-Burmese War First Anglo-Afghan War First Anglo-Sikh War Anglo-Persian War Indian Rebellion |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath |

| Relations | Sir Henry Havelock-Allan, 1st Baronet (son) |

Early life

Henry Havelock was born at Ford Hall, Bishopwearmouth (now in Sunderland), the son of William Havelock, a wealthy shipbuilder, and Jane, daughter of John Carter, solicitor, of Stockton-on-Tees. He was the second of four brothers, all of whom entered the army.[1] The family moved to Ingress Park, Greenhithe, Kent, when Henry was still a child, and here his mother died in 1811. From January 1800 until August 1804 Henry attended Dartford Grammar School[2] as a parlour boarder with the Master, Rev John Bradley,[3] after which he was placed with his elder brother in the boarding-house of Dr. Raine, headmaster of Charterhouse School until he was 17.[4] Among his contemporaries at Charterhouse were Connop Thirlwall, George Grote, William Hale, Julius Hare, and William Norris (Recorder of Penang), the last two being his special friends. Shortly after leaving Charterhouse his father lost his fortune by unsuccessful speculation, sold Ingress Hall, and removed to Clifton.[1]

In accordance with the desire of his mother he entered the Middle Temple in 1813, and became a pupil of Joseph Chitty; his fellow-student was Thomas Talfourd. Havelock was thrown upon his own resources, and obliged to abandon the law as a profession.[1] By the good offices of his brother William, who had distinguished himself in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo, he obtained on 30 July 1815, at the age of 20, a post as second lieutenant in the 95th Regiment of Foot, Rifle Brigade, and was posted to the company of Captain Harry Smith, who encouraged him to study military history and the art of war. He was promoted lieutenant on 24 October 1821. During the following eight years of service in Britain he read extensively all the standard works and acquired a good acquaintance with the theory of war.[1]

India

Seeing no prospect of active service, he resolved to go to India, and at the end of 1822 transferred into the 13th (1st Somersetshire) Regiment (Light Infantry), then commanded by Major Robert Sale, and embarked on the General Kyd in January 1823 for India.[5] Before embarkation he studied the Persian and Hindustani languages with success under John Borthwick Gilchrist. During the voyage a brother officer, Lieutenant James Gardner, awakened in Havelock religious convictions which had slumbered since his mother's death, but henceforth became the guiding principle of his life.[1]

Havelock served with distinction in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826), after which he returned to England and married Hannah Shepherd Marshman, the daughter of eminent Christian missionaries Dr. and Mrs. Joshua Marshman. At about the same time he became a Baptist, being baptized by Mr. John Mack at Serampore.[1] He introduced some of his new family's missionary ideas to the army and began the distribution of bibles to all soldiers. He also introduced all-rank bible study classes and established the first non-church services for military personnel.[6]

First Afghan War

By the time Havelock took part in the First Anglo-Afghan War in 1839, he had been promoted to the rank of captain. He was present as aide-de-camp to Willoughby Cotton at the capture of Ghazni, on 23 May 1839, and at the occupation of Kabul. After a short period in Bengal to secure the publication of his Memoirs of the Afghan Campaign, he returned to Kabul in charge of recruits, and became interpreter to General William George Keith Elphinstone.[1]

In 1841, being attached to Sir Robert Henry Sale's force, he took part in the celebrated passage of the defiles of the Ghilzais and in the fighting from Tezeen to Jalalabad. Here, after many months siege, his column in a sortie en masse defeated Akbar Khan on 7 April 1842. He was now made Deputy Lieutenant-General of the infantry division in Kabul, and in September he assisted at Jagdalak, at Tezeen, and at the release of the British prisoners at Kabul, besides taking a prominent part at Istalif. He next went through the Gwalior campaign as Persian interpreter to Sir Hugh Gough, and distinguished himself at Maharajpur in 1843, and also in the Sikh Wars at the battles of Mudki, Ferozeshah and Sobraon in 1845.[1]

He used his spare time to produce analytical reports about the skirmishes and battles in which he was involved. These writings were returned to Britain and were reported on in the press of the day. For his military services he was made Deputy Adjutant-General at Bombay. He transferred from the 13th Regiment of Foot to the 39th, then as second major into the 53rd at the beginning of 1849, and soon afterwards left for England, where he spent two years[1] and became involved in the running of the Stepney Baptist Academy, soon to move to Regent's Park. He returned to India in 1852 with further promotion: he was appointed Quartermaster-General, promoted to full colonel, and appointed Adjutant-General, India in November 1854.[7]

Indian Rebellion of 1857–1859

In that year, he was selected by Sir James Outram to command a division in the Anglo-Persian War, during which he was present at the action of Muhamra against the forces of Nasser al-Din Shah under command of Khanlar Mirza. Peace with Persia freed his troops just as the Indian Rebellion broke out; and he was chosen to command a column to quell disturbances in Allahabad, to support Sir Henry Lawrence at Lucknow and Wheeler at Cawnpore, and to pursue and utterly destroy all mutineers and insurgents.[1] Throughout August Havelock led his soldiers northwards across Oudh (present day Uttar Pradesh), defeating all rebel forces in his path, despite being greatly outnumbered. His years of study of the theories of war and his experiences in earlier campaigns were put to good use. At this time Lady Canning wrote of him in her diary: "General Havelock is not in fashion, but all the same we believe that he will do well." But in spite of this lukewarm commendation Havelock proved himself the man for the occasion and won a reputation as a great military leader.[1]

Three times he advanced for the relief of the Lucknow, but twice held back rather than risk fighting with troops wasted by battle and disease.[1] Reinforcements arrived at last under Outram, who assumed command. With Havelock commanding the assault, Lucknow was relieved on 25 September 1857. However, a second rebel force arrived and besieged the town again. This time Havelock and his troops were caught inside the blockade.[1]

Death

.jpg.webp)

He died in Lucknow on 24 November 1857 of dysentery, a few days after the siege was lifted. He lived long enough to receive news that he was to be created a Baronet for the first three battles of the campaign; but he never knew of the major-generalship which was conferred shortly afterwards. With his baronetcy came a pension of £1,000 a year voted by Parliament. He was also appointed Colonel of the 3rd (East Kent) Regiment of Foot ("The Buffs") in December, as news of his death had yet to reach England. The baronetcy was afterwards bestowed upon his eldest son, Henry, in the following January; while to his widow, by Royal Warrant of Precedence, were given the rights to which she would have been entitled had her husband survived and been created a baronet.[1] Parliament awarded pensions of £1,000 a year each to widow and son.[1]

Tomb in Lucknow

Legacy

Statue in Trafalgar Square

There is a statue of Havelock (by William Behnes) in Trafalgar Square, London. The plaque on the plinth reads:

To Major General Sir Henry Havelock KCB and his brave companions in arms during the campaign in India 1857. "Soldiers! Your labours, your privations, your sufferings and your valour, will not be forgotten by a grateful country." H. Havelock

In 2000, there was a controversy when the then mayor of London, Ken Livingstone suggested that the Trafalgar Square statue, together with that of General Charles James Napier, be replaced with "more relevant" figures.[8]

Statue in Mowbray Park

William Behnes also designed the statue of Havelock at the top of Building Hill in Mowbray Park Sunderland. Two cannon (replicas of cannons presented to Sunderland after the Crimean War in 1857) stand beside the statue, facing north commanding the view over the park. The statue, however, looks west towards Havelock's birthplace. The statue reads: Born 5, April 1795 at Ford Hall Bishopwearmouth Died 24 November 1857 at Dil-Koosa Lucknow.[9]

An imposing monument to Havelock's memory was erected by his sons, widow, and family. His tomb still stands in Chander Nagar – Alambagh area of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. These verses are inscribed on his tomb: " His ashes in a peaceful urn shall rest; His name a great example stands, to show How strangely high endeavours may be blessed, When piety and valour jointly go." [10]

Other

- Havelock MRT station and Havelock Road along Singapore River, Singapore[11][12]

- Havelock Island, in the Andaman Islands was also named in his honour (now Swaraj Dweep).[13]

- Several public Houses in England are named "The General Havelock":[14] The Haydon Bridge pub sign bears his portrait, as does the East Sleekburn one; in addition, there is a road/street called Havelock Mews next to the latter.[15]

- Havelock Road in Luton is claimed to be named after him.[16] The road appears on The 1887 1st edition and 1901 2nd edition OS maps[17]

- Havelock Guest House in Jersey.[18]

- The New Zealand towns of Havelock, on the South Island, and Havelock North, on the North Island, are named after him.[19][20]

- Havelock Road in Southall, London, was to be renamed Guru Nanak Road in 2021.[21][22]

- Havelock, North Carolina, a city in coastal North Carolina[23]

- The town of Havelock, Nebraska, which was incorporated in 1893 but was later annexed by the City of Lincoln, was named after him. The former area of the town is still known today as the Havelock neighborhood in Lincoln.[24]

- Havelock Street in Sunnyside, San Francisco, California established in 1880.[25]

In fiction

Havelock, referred to as Gravedigger Havelock, appears as a character in several of the Flashman novels by George MacDonald Fraser - Flashman,[26] Flashman and the Mountain of Light[27] and Flashman in the Great Game.[28] He is portrayed as a very competent officer[28] and an exceptionally religious man.[27]

Published works

- Havelock, Henry (1840). Narrative of the War in Affghanistan 1838–39. London: Henry Colburn. OCLC 36579435.

References

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Havelock, Sir Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80.

- Brock, William (1858). "A biographical sketch of sir Henry Havelock. Copyright ed". Tauchnitz.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Wilmington churchyard M.I.'s". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Parish, W. D. List of Carthusians, 1800–1879. (14 January 2009). In Wikisource, The Free Library. Retrieved 07:57, 14 January 2009, from

List of Carthusians, letter H.

List of Carthusians, letter H. - "The Fight of Faith: lives and testimonies from the battlefield" Bray, P./Claydon, M. (Eds) Ch 8 p102 (Pollock, J.): London, Panoplia, 2013 ISBN 978-0-9576089-0-0

- "Sir Henry Havelock". British Empire. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "No. 21638". The London Gazette. 8 December 1854. p. 3991.

- Kelso, Paul (20 October 2000). "Mayor attacks generals in battle of Trafalgar Square". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Sunderland, TWSU22, Sculpture, Monument to Major General Sir Henry Havelock Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Lucknow album : containing a series of fifty photographic views of Lucknow and its environs together with a large sized plan of the city". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Meet Hajijah and Boon Tat: 10 Singapore roads named after someone's grandmother or grandfather". The Straits Times. 25 May 2017.

- National Library Board, Singapore. "Havelock Road". Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "PM Narendra Modi renames 3 islands of Andaman Nicobar". The Indian Times. 30 December 2018.

- "Pub information: Search results". Beerintheevening.com. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "East Sleekburn". East Sleekburn.

- "Luton on Sunday – 28/02/2016 digital edition". Retrieved 28 February 2016. page 23.

- "Archaeology Data Service: myADS" (PDF). Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Jersey Hotel: Havelock Guest House". www.havelockguesthouse.com. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Havelock | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz.

- "Havelock North | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz.

- "Road in Southall named after British general who suppressed 1857 uprising is now Guru Nanak Road". Indian Express. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Curling, Cheryl. "Southall road to be named after Guru Nanak". www.ealing.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "History". Havelock, North Carolina. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Fitzpatrick, Lilian Linder (1925). "Lancaster County". Nebraska Place-Names. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- "San Jose at Havelock: 1910 and Today". Sunnyside History. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- Fraser, George MacDonald (1969). Flashman : from the Flashman papers, 1839-1842. London. ISBN 0-257-66799-7. OCLC 29733.

I didn't find out what, though, until the following day, when Sale came back again with the gravedigger at his elbow - he was Major Havelock, by the way, a Bible-moth of the deepest dye, and a great name now

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - George MacDonald Fraser (1991). Flashman and the Mountain of Light. Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-617980-1.

I was about to sidle off to the staff mess when I heard a great groan close by, and there was old Gravedigger Havelock, clasping his bony paws in supplication and looking like Thomas Carlyle with rheumatics—I never seemed to see that man but he was calling on God for something or other: possibly it was the sight of me that did it.

- George MacDonald Fraser (2006). Flashman in the Great Game (the Flashman Papers, Book 8). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-721719-9.

...and since I had to be here I'd rather be under Havelock's wing than anyone's. He was a good soldier, you see, and as canny as Campbell in his own way; there'd be no massacres or Last Stands round the Union Jack with the Gravedigger in charge.

Bibliography

- Brock, William (1858). A Biographical Sketch of Sir Henry Havelock, K. C. B. Leipzig: Tauchnitz.

- Marshman, John Clark (1860). Memoirs of Major-General Sir Henry Havelock, K.C.B. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80.

- Pollock, John (1996) [1963]. Way to Glory: the biography of General Henry Havelock. Christian Focus Publications. ISBN 978-1-85792-245-5.