Henry Middleton (captain)

Sir Henry Middleton (died 1613) was a sea captain and adventurer. He negotiated with the sultan of Ternate and the sultan of Tidore, competed against Dutch and Portuguese interests in the East Indies but still managed to buy cloves.[1] He had two brothers, John Middleton (d. 1602 or 1603), the eldest who was captain of EIC galleon Hector and director of EIC. David Middleton was also a mariner working for EIC.

Henry was taken on at the Woolwich ship yards working first on the East India Company's Red Dragon. The company was organising its first expedition to "East India". The prominent Elizabethan trader and privateer, James Lancaster was to command the four ships. Second in command was Middleton's brother John, a company captain who secured Henry as a mercantile agent with a berth on the voyage. They set off in April 1601 arriving in Aceh, Sumatra in June 1602.[1]

Middleton was sent onwards to Priaman on the west coast where he procured substantial quantities of pepper and cloves before returning home safely in the summer of 1603.[1]

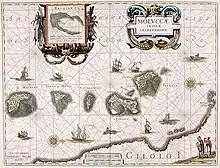

In 1604 Middleton commanded a second voyage heading for the islands of Ternate, Tidore, Ambon and Banda in the Moluccas with his brother David Middleton as second captain.[2] They would encounter severe Dutch East India Company hostility, which saw the beginning of Anglo-Dutch competition for access to spices.[3]

Second voyage

Outward bound

The Second Voyage used the same four ships. With the Red Dragon now under the command of Middleton,[4] the fleet departed Gravesend on 25 March 1604 but were delayed at the Downs as they did not have the correct complement of men.[5] Middleton had lost the beneficial wind conditions[6] but ordered that they should sail on to Plymouth and discharge the extra men there.[7] Despite these delays, on 7 April, the fleet passed Cabo da Roca, the westernmost extent of mainland Portugal. By 15 April they reached the Canary Islands and sailed on to the central Atlantic Ocean.[7] On 24 April, 570 kilometres off the coast of Western Africa, they anchored at Maio, Cape Verde and went ashore in search of fresh food and water.[8] They were due to set sail early the next morning, but became aware that one of their merchants was missing.[9] A search party of 150 men searched for a day, but failed to find him, and Middleton resolved to leave without him.[9]

The fleet crossed the equator on 16 May, and sighted the Cape of Good Hope just under two months later.[10] At least eighty of the crew were suffering from scurvy but, with the weather against them, it was six days before they could get their sick on land.[11] Having landed at Table Bay, the company traded successfully with the local inhabitants, securing over two hundred sheep and a number of "beeves".[12] On 3 August, Middleton took his pinnace and a company of men in other boats to hunt whales in the bay.[13] Having harpooned one whale a larger animal attacked, causing the boat to flood and Middleton to take refuge on another of the boats. With great difficulty, the pinnace was rescued and brought ashore where it took the ship's carpenters three days to repair. The younger whale was dragged to shore;[14] its oil was intended for their lamps, but a combination of the small size of the whale and bad casks provided the company with less than they would have liked.[15]

Following attacks from the native population, the fleet's company returned to their ships on 14 August, and then, with fair winds, set sail five days later.[16]

East India

On 21 December, the fleet anchored within the islands of Sumatra. They had lost a number of men to scurvy and Middleton himself was too ill to land and present the King of Bantam with a letter from King James until 31 December. It was decided that the Hector and Susan would return to England with their cargoes of pepper[17] and the Red Dragon and Ascension would proceed eastwards to acquire cloves and nutmeg. The ships departed on 16 January, and just under a month later made anchor off Ambiona having lost more men to flux on the way.[18] Here they gained permission from the Portuguese commander to trade on the island but considered the prices asked too high.[19] However, a Dutch fleet now arrived taking the fort by force and cutting off Middleton's opportunity to trade. The Dutch had also beaten the English to the Banda Islands, where they were offering the same commodities as Middleton had to offer.[20] In view of this, Middleton decided to split up the two vessels, with the Red Dragon sailing to the Moluccas for cloves and the Ascension making for the isles of Banda to acquire nutmeg and mace.[20] Sailing for a month, against both wind and current,[21] the Dragon became the first English merchant vessel to reach the Moluccas on 18 March 1605.[1]

Tidore and Ternate

The company purchased fresh supplies from the people of Makian, an island mostly sworn to the king of Ternate, with the exception of the town of Taffasoa, which was sworn to the king of Tidore. The natives refused to trade cloves without permission from the Ternate king. Duly, the Dragon sailed on towards the more eastward islands of Tidore and Ternate. On 22 March, the crew became involved in the friction between Tidore and Ternate. Two Ternatan caracoas[note 1] were being chased by seven Tidore warboats[22] and hailed the Red Dragon for help. The lead boat contained the King of Ternate and three Dutch merchants who pleaded with Middleton to rescue the second vessel, which contained more Dutch. The Tidores boarded the Ternate vessel, killing all but three who managed to swim to the safety of the Dragon.[23] Middleton attempted to persuade the Ternatans to allow a trade monopoly and the establishment of an English factory but he lacked the authority needed to pledge the required protection from both Portuguese and Dutch aggression.[1]

Middleton arrived at Tidore on 27 March, and the following day met Thomè de Torres, captain of one of the Portuguese galleon. Middleton declared that if they would not accept peaceable trade, he would have just cause to join the Dutch in war against them. The Red Dragon traded successfully and remained at Tidore for the next three weeks, acquiring all but 80 bahars.[note 2] of the cloves on the island. The remaining cloves were unavailable as they belonged to Portuguese merchants of Malacca Town.[24]

In April 1605, the Red Dragon prepared to return to Makian. On their arrival at seven the following evening, Middleton sent his brother along with two Ternatans to present the governor with letters from both kings permitting trade. After a public reading of the letter, the governor announced that there were no ripe cloves on the island, and Middleton, suspecting Ternatan duplicity, decided to sail for Taffasoa where the English managed to acquire more cloves just before the Ternate attacked the town. They returned to Tidore on 3 May having received word from the fort of a Dutch attack.[25]

In addition to the Dutch fleet, the king of Ternate and all his caracoas were there, as part of the attack on their enemies. The Red Dragon received a cold reception from the Dutch, who claimed that a Gujarati had told them that they had assisted the Portuguese during the last battle. The Dutch then described the battle ensuing, and their plans to attack the fort on the next day. That evening Captain de Torres came aboard and told Middleton that they (the Portuguese) were sure of victory against the Dutch, and would trade any remaining cloves with the English. At around one in the afternoon on 7 May, the Dutch and Ternate attacked, firing all their ordnance at the fort. During particularly heavy fire, the attacking forces landed men on the island, a little north of the town, who entrenched themselves there for the night. The attack continued the next morning, and the landed men were now within a mile of the fort and set up a large piece of ordnance to further bombard the fort. The morning of 9 May, the attack began before sunrise, and catching the Portuguese unaware, the Dutch and Ternate scaled the walls and raised their colours in the fort. During the ensuing battle, the Portuguese and Tidorean forces got the upper hand and drove their enemies from the fort, forcing them to drop their weapons and retreat into the sea. Just as the battle seemed won, the fort exploded, and the combined Dutch and Ternatan forces rallied. The Portuguese retreated once more, sacking the town as they did so, burning the factory with the cloves and leaving nothing of worth.[26]

Sixth voyage

By 1610 East India Company's ships were making regular voyages. Middleton in the Trade's Increase was tasked with establishing trade in Surat, western India. In November, they arrived at Socotra, an island east of the Horn of Africa. Here the crew were advised of better trading in Aden, part of the Ottoman Empire. Middleton left the Peppercorn, one of the three ships at Aden before sailing on to Mocha, Yemen.

As commander Middleton went ashore at Mocha and was greeted with great pomp by the Agha, but a week later the English were attacked and robbed by their hosts. Eight were killed and Middleton and seven others were chained up by the neck. Meanwhile, his ship, The Darling successfully repelled three boatloads of soldiers. He escaped but found in Surat the company's representatives had been forced to abandon trading due to Portuguese pressure on the local authorities. He subsequently spent eighteen fruitless months trying to establish a new trading post.[1][27]

References

- Margaret Makepeace, 'Middleton, Sir Henry (d. 1613)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Middleton, David". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Middleton, David". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 110. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Corney, Bolton; Middleton, Sir Henry (1855). The voyage of Sir Henry Middleton to Bantam and the Maluco Islands; being the second voyage set forth by the governor and company of merchants of London trading into the East-Indies (1855 ed.). London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 1.

- Corney (1855), pp1–2.

- Corney (1855), pp2–3.

- Corney (1855), p3.

- Corney (1855), pp4–5.

- Corney (1855), p6.

- Corney (1855), pp6–7.

- Corney (1855), pp7–8.

- Corney (1855), p9.

- Corney (1855), pp9–10.

- Corney (1855), pp10–11.

- Corney (1855), p11.

- Corney (1855), p14.

- Corney (1855), p18.

- Corney (1855), pp19–23.

- Corney (1855), pp24–25.

- Corney (1855), p28.

- Corney (1855), pp29–33.

- Corney (1855), p33.

- Corney (1855), p34.

- Corney (1855), pp34–45

- Corney (1855), pp46–50.

- Corney (1855), pp50–56.

- Elizabeth Baigent, 'Downton, Nicholas (bap. 1561, d. 1615)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008

- ancient Austranesian boats used for war and trading

- A unit in the trading system that stretched from the ports of China, the East Indies, India and eastern Africa.