Banda Islands

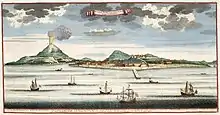

The Banda Islands (Indonesian: Kepulauan Banda) are a volcanic group of ten small volcanic islands in the Banda Sea, about 140 km (87 mi) south of Seram Island and about 2,000 km (1,243 mi) east of Java, and constitute an administrative district (kecamatan) within the Central Maluku Regency in the Indonesian province of Maluku. The islands rise out of 4-to-6-kilometre (2.5 to 3.7 mi) deep ocean and have a total land area of approximately 172 square kilometres (66 sq mi). They had a population of 18,544 at the 2010 Census[2] and 20,924 at the 2020 Census.[3] Until the mid-19th century the Banda Islands were the world's only source of the spices nutmeg and mace, produced from the nutmeg tree. The islands are also popular destinations for scuba diving and snorkeling. The main town and administrative centre is Banda Neira, located on the island of the same name.

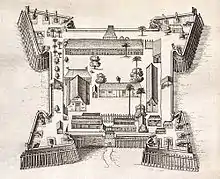

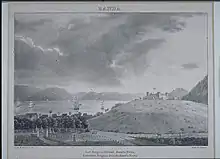

Banda Besar island seen from Fort Belgica | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Southeast Asia |

| Coordinates | 4°35′S 129°55′E |

| Archipelago | Maluku Islands |

| Total islands | 11 (7 inhabited) |

| Major islands | Banda Besar, Neira, Banda Api, Pulau Hatta, Pulau Ay, Pulau Rhun |

| Area | 172 km2 (66 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 641 m (2103 ft)[1] |

| Highest point | Gunung Api |

| Administration | |

| Province | Maluku |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 20,924 (2020) |

| Pop. density | 121.65/km2 (315.07/sq mi) |

History

Pre-European history

The first documented human presence in the Banda Islands comes from a rock shelter site on Pulau Ay that was in use at least 8,000 years ago.[4]

The earliest mention of the Banda Islands are found in Chinese records dating as far back as 200 BCE though there is speculation that it is mentioned in earlier Indian sources. The Srivijaya Kingdom had extensive trade contacts with the Banda Islands. Also during this period (from the late 13th century and onwards) Islam arrived in the region. It soon became established in the area.[5]

Before the arrival of Europeans, Banda had an oligarchic form of government led by orang kaya ('rich men') and the Bandanese had an active and independent role in trade throughout the archipelago.[6]: 24 Banda was the world's only source of nutmeg and mace, spices used as flavourings, medicines, and preserving agents that were at the time highly valued in European markets. They were sold by Arab traders to the Venetians for exorbitant prices. The traders did not divulge the exact location of their source and no European was able to deduce their location.

The first written accounts of Banda are in Suma Oriental, a book written by the Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires who was based in Malacca from 1512 to 1515 but visited Banda several times. On his first visit, he interviewed the Portuguese and the far more knowledgeable Malay sailors in Malacca. He estimated the early sixteenth century population to be 2500–3000. He reported the Bandanese as being part of an Indonesia-wide trading network and the only native Malukan long-range traders taking cargo to Malacca, although shipments from Banda were also being made by Javanese traders.

In addition to the production of nutmeg and mace, Banda maintained significant entrepôt trade; goods that moved through Banda included cloves from Ternate and Tidore in the north, bird-of-paradise feathers from the Aru Islands and Western New Guinea, massoi bark for traditional medicines and salves. In exchange, Banda predominantly received rice and cloth; namely light cotton batik from Java, calicoes from India and ikat from the Lesser Sundas. In 1603, an average quality sarong-sized cloth traded for eighteen kilograms of nutmeg. Some of these textiles were then sold on, ending up in Halmahera and New Guinea. Coarser ikat from the Lesser Sundas was traded for sago from the Kei Islands, Aru and Seram.

Portuguese

In August 1511, on behalf of the king of Portugal, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, which at the time was a major hub of Asian trade. In November of that year, after having secured Malacca and learned of the Banda Islands' location, Albuquerque sent an expedition of three ships led by his good friend António de Abreu to find them. Malay pilots, either recruited or forcibly conscripted, guided them via Java, the Lesser Sundas and Ambon to Banda, arriving in early 1512.[7]: 7 [8]: 5, 7 The first Europeans to reach the Banda Islands, the expedition remained in Banda for about one month, purchasing and filling their ships with Banda's nutmeg, mace, and cloves, in which Banda had a thriving entrepôt trade.[7]: 7 D'Abreu sailed through Ambon and Seram while his second in command Francisco Serrão went ahead towards the Maluku islands, was shipwrecked and ended up in Ternate.[6]: 25

Distracted by hostilities elsewhere in the archipelago, such as Ambon and Ternate, the Portuguese did not return to the Banda Islands until 1529, when Portuguese trader Captain Garcia Henriques landed troops. Five of the Banda islands were within gunshot of each other and Henriques realised that a fort on the main island Neira would give him full control of the group. The Bandanese were, however, hostile to such a plan, and their warlike antics were both costly and tiresome to Garcia whose men were attacked when they attempted to build a fort. From then on, the Portuguese were infrequent visitors to the islands, preferring to buy their nutmeg from traders in Malacca.[8]: 5, 7

Unlike inhabitants of other eastern Indonesian islands visited by the Portuguese, such as Ambon, Solor, Ternate and Morotai, the Bandanese displayed no enthusiasm for Christianity or the Europeans who brought it in the sixteenth century, and no serious attempt was made to Christianise the Bandanese.[6]: 25 Maintaining their independence, the Bandanese never allowed the Portuguese to build a fort or permanent post in the islands. Ironically, it was this lack of presence which attracted the Dutch to trade in Banda instead of the clove-producing islands of Ternate and Tidore.

Dutch control

The Dutch followed the Portuguese to Banda but were to have a much more dominating and lasting presence. Dutch–Bandanese relations were mutually resentful from the outset, with Holland's first merchants complaining of Bandanese reneging on agreed deliveries and price, and cheating on quantity and quality. For the Bandanese, on the other hand, although they welcomed another competitor purchaser for their spices, the items of trade offered by the Dutch—heavy woolens, and damasks, unwanted manufactured goods, for example—were usually unsuitable in comparison to traditional trade products. The Javanese, Arab and Indian, and Portuguese traders for example brought indispensable items along with steel knives, copper, medicines, and prized Chinese porcelain.

As much as the Dutch disliked dealing with the Bandanese, the trade was a highly profitable one with spices selling for 300 times the purchase price in Banda. This amply justified the expense and risk in shipping them to Europe. The allure of such profits saw an increasing number of Dutch expeditions; it was soon seen that in trade with the East Indies, competition from each would eat into all their profits. Thus the competitors united to form the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) (the United East India Company, referred to in English as the Dutch East India Company) in 1602.[7]

Until the early seventeenth century the Bandas were ruled by a group of leading citizens, the orang kaya (literally 'rich men'); each of these was head of a district. At the time nutmeg was one of the "fine spices" kept expensive in Europe by disciplined manipulation of the market, but a desirable commodity for Dutch traders in the ports of India as well; economic historian Fernand Braudel notes that India consumed twice as much as Europe.[9] A number of Banda's orang kaya were persuaded by the Dutch to sign a treaty granting the Dutch a monopoly on spice purchases. Even though the Bandanese had little understanding of the significance of the treaty known as 'The Eternal Compact', or that not all Bandanese leaders had signed, it would later be used to justify Dutch troops being brought in to defend their monopoly.

In April 1609, Admiral Pieter Willemsz. Verhoeff arrived at Banda Neira with a request by Maurice, Prince of Orange to build a fort on the island (the eventual Fort Nassau). The Bandanese were not excited about this idea. On 22 May, before building of the fort had started, the orang kaya called a meeting with the Dutch admiral, purportedly to negotiate prices. Instead, they led Verhoeff and two high-ranked men into an ambush and decapitated them and subsequently killed 46 of the Dutch visitors. Jan Pietersz Coen, who was a lower-ranked merchant on the expedition, managed to escape, but the traumatic event likely influenced his future attitude towards the Bandanese.[10]: 95–98

English–Dutch rivalry

While Portuguese and Spanish activity in the region had weakened, the English had built fortified trading posts on tiny Ai and Run islands, ten to twenty kilometres from the main Banda Islands. With the English paying higher prices, they were significantly undermining Dutch aims for a monopoly. As Anglo-Dutch tensions increased in 1611 the Dutch built the larger and more strategic Fort Belgica above Fort Nassau.

In 1615, the Dutch invaded Ai with 900 men, whereupon the English retreated to Run where they regrouped. Japanese mercenaries served in the Dutch forces.[11] That same night, the English launched a surprise counter-attack on Ai, retaking the island and killing 200 Dutchmen. A year later, a much stronger Dutch force attacked Ai. This time the defenders were able to hold off the attack with cannon fire, but after a month of siege they ran out of ammunition. The Dutch killed the defenders, and afterwards strengthened the fort, renaming it 'Fort Revenge'.

Massacre of the Bandanese

Newly appointed VOC governor-general Jan Pieterszoon Coen set about enforcing Dutch monopoly over the Banda's spice trade. In 1621 well-armed soldiers were landed on Bandaneira Island and within a few days they had also occupied neighbouring and larger Lontar. The orang kaya were forced at gunpoint to sign an unfeasibly arduous treaty, one that was in fact impossible to keep, thus providing Coen an excuse to use superior Dutch force against the Bandanese.[7] The Dutch quickly noted a number of alleged violations of the new treaty, in response to which Coen launched a punitive massacre. Japanese mercenaries were hired to deal with the orang kaya,[12] forty of whom were beheaded with their heads impaled and displayed on bamboo spears.[13] The butchering and beheadings were carried out by the Japanese for the Dutch.[14]

The islanders were tortured and their villages destroyed by the Dutch.[15][16] The Bandanese chiefs were also tortured by the Dutch and Japanese.[17][18]

The Dutch carved 68 parcels out of the islands after the enslavement and slaughter of the natives.[19][20]

The population of the Banda Islands prior to Dutch conquest is generally estimated to have been around 13,000–15,000 people, some of whom were Malay and Javanese traders, as well as Chinese and Arabs. The actual numbers of Bandanese who were killed, forcibly expelled or fled the islands in 1621 remain uncertain. But readings of historical sources suggest around one thousand Bandanese likely survived in the islands, and were spread throughout the nutmeg groves as forced labourers.[7]: 54 [21]: 18 [22][23] The Dutch subsequently re-settled the islands with imported slaves, convicts and indentured labourers (to work the nutmeg plantations), as well as immigrants from elsewhere in Indonesia. Most survivors fled as refugees to the islands of their trading partners, in particular Keffing and Guli Guli in the Seram Laut chain and Kei Besar.[7] Shipments of surviving Bandanese were also sent to Batavia (Jakarta) to work as slaves in developing the city and its fortress. Some 530 of these individuals were later returned to the islands because of their much-needed expertise in nutmeg cultivation (something sorely lacking among newly arrived Dutch settlers).[7]: 55 [21]: 24

Whereas up until this point the Dutch presence had been simply as traders, that was sometimes treaty-based, the Banda conquest marked the start of the first overt colonial rule in Indonesia, albeit under the auspices of the VOC.

VOC monopoly

Having nearly eradicated the islands' native population, Coen divided the productive land of approximately half a million nutmeg trees into sixty-eight 1.2-hectare perken. These land parcels were then handed to Dutch planters known as perkeniers of which 34 were on Lontar, 31 on Ai and 3 on Neira. With few Bandanese left to work them, slaves from elsewhere were brought in.[24] Now enjoying control of the nutmeg production, the VOC paid the perkeniers 1⁄122nd of the Dutch market price for nutmeg; however, the perkeniers still profited immensely, building substantial villas with opulent imported European decorations.

The outlying island of Run was harder for the VOC to control and they exterminated all nutmeg trees there. The production and export of nutmeg was a VOC monopoly for almost two hundred years. Fort Belgica, one of many forts built by the Dutch East India Company, is one of the largest remaining European forts in Indonesia.

English–Dutch rivalry continues

Though not physically present at the Banda Islands, the English claimed the small island of Run until 1667 when, under the Treaty of Breda, the Dutch and English agreed to maintain the colonial status quo and relinquish their respective claims.

In 1810, the Kingdom of Holland was a vassal of Napoleonic France and hence in conflict with Britain. The French and British were each seeking to control lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes. On 10 May 1810, a squadron consisting of the 36-gun frigate HMS Caroline, HMS Piedmontaise (formerly a French frigate), 18-gun sloop HMS Barracouta, and the 12-gun transport HMS Mandarin left Madras with money, supplies and troops to support the garrison at Amboyna, recently captured from the Dutch. The frigates and sloop carried a hundred officers and men of the Madras European Regiment, while the Mandarin carried supplies. The squadron was commanded by Captain Christopher Cole, with Captain Charles Foote on the Piedmontaise and Captain Richard Kenah aboard the Barracouta. After departing from Madras, Cole informed Foote and Kenah of Cole's plan to capture the Bandas; Foote and Kenah agreed. In Singapore, Captain Spencer informed Cole that over 700 regular Dutch troops may have been located in the Bandas.[25][26]

The squadron took a circuitous route to avoid alerting the Dutch. On 9 August 1810, the British appeared at Banda Neira. They quickly stormed the island and attacked Belgica Castle at sunrise. The battle was over within hours, with the Dutch surrendering Fort Nassau – after some subterfuge – and within days the remainder of the Banda Islands. After the Dutch surrender, Captain Charles Foote (of the Piedmontaise) was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Banda Islands. This action was a prelude to Britain's invasion of Java in 1811.[25]

Before the Dutch retook control of the islands, the British removed many nutmeg trees and transplanted them to Ceylon and other British colonies. The competition largely destroyed the value of the Banda Islands to the Dutch.[27]

Recent history

In the late 1990s, violence between Christians and Muslims spilled over from intercommunal conflict in Ambon. The disturbance and resulting deaths damaged the previously prosperous tourism industry.[28]

Geography

There are seven inhabited islands and several that are uninhabited. The inhabited islands are:

Main group (formed from the drowned caldera of a former volcano):

- Banda Neira, or Naira, the island with the administrative capital and a small airfield (as well as accommodation for visitors). Present on Banda Neira is Fort Belgica, one of the largest remaining Dutch forts that are still intact in Indonesia.

- Banda Api, an active volcano (Gunung Api) with a peak of about 650 m

- Banda Besar, or Lonthoir, is the largest island (Indonesian besar, big), 12 km (7 mi) long and 3 km (2 mi) wide. It has three main settlements, Lonthoir, Selamon and Waer.

Some distance to the west:

- Pulau Ai or Pulau Ay

- Pulau Run, further west again. In the 17th century, this island was involved in an exchange between the British and the Dutch: it was exchanged for the island of Manhattan in New York.

To the east:

- Pulau Pisang (Banana Island), also known as Syahrir.

To the southeast:

- Pulau Hatta, formerly Rosengain or Rozengain

Others, possibly small and/or uninhabited, are:

- Nailaka, a short distance northeast of Pulau Run

- Batu Kapal, a small island northwest of Pulau Pisang

- Manuk, an active volcano

- Pulau Keraka or Pulau Karaka (Crab Island), a short distance north of Banda Api

- Manukang or Suanggi, to the northwest of the main group

- Hatta Reef

The islands are part of the Banda Sea Islands moist deciduous forests ecoregion.

Demographics

Language

Bandanese speak Banda Malay, which has several features distinguishing it from Ambonese Malay, a Malay dialect that is a lingua franca in central and southern Maluku alongside Indonesian. Banda Malay is famous in the region for its unique, lilting accent, but it also has a number of locally identifying words in its lexicon, many of them borrowings or loanwords from Dutch.

Examples:

- fork: forok (Dutch vork)

- ant: mir (Dutch mier)

- spoon: lepe (Dutch lepel)

- difficult: lastek (Dutch lastig)

- floor: plur (Dutch vloer)

- porch: stup (Dutch stoep)

Banda Malay shares many Portuguese loanwords with Ambonese Malay not appearing in the national language, Indonesian. But it has comparatively fewer, and they differ in pronunciation.

Examples:

- turtle: tetaruga (Banda Malay); totoruga (Ambonese Malay) (from Portuguese tartaruga)

- throat: gargontong (Banda Malay); gargangtang (Ambonese Malay) (from Portuguese garganta)

Finally, and most noticeably, Banda Malay uses some distinct pronouns. The most immediately distinguishing is that of the second person singular familiar form of address: pané.

The descendants of some of the Bandanese who fled Dutch conquest in the seventeenth century live in the Kai Islands (Kepulauan Kei) to the east of the Banda group, where a version of the original Banda language is still spoken in the villages of Banda Eli and Banda Elat on Kai Besar Island. While long integrated into Kei Island society, residents of these settlements continue to value the historical origins of their ancestors.

Culture

Most of the present-day inhabitants of the Banda Islands are descended from migrants and plantation labourers from various parts of Indonesia, as well as from indigenous Bandanese. They have inherited aspects of pre-colonial ritual practices in the Banda Islands that are highly valued and still performed, giving them a distinct and very local cultural identity.[29]

See also

Further reading

- Ghosh, Amitav (2021). The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 1529369479.

- Giles Milton. Nathaniel's Nutmeg: How One Man's Courage Changed the Course of History (Sceptre books, Hodder and Stoughton, London)

Notes

- "G. Banda Api". Badan Geologi. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- Lape, Peter (2013). "Die erste Besiedlung auf den Banda-Inseln: 8000 Jahre Archäologie auf den Molukken" [The first settlement in the Banda Islands: 8000 years of archeology in the Moluccas]. Antike Welt. 5 (13): 9–13.

- Schellinger, Paul; Salkin, Robert, eds. (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 5: Asia and Oceania. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333576892.

- Hanna, Willard A. (1991). Indonesian Banda: Colonialism and Its Aftermath in the Nutmeg Islands. Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Naira. ISBN 9780915980918.

- Milton, Giles (1999). Nathaniel's Nutmeg. London: Sceptre. ISBN 9780340696767.

- Braudel, Fernand (1984). Civilization and Capitalism: 15th–18th Century. Vol. III: The Perspective of the World. London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd. p. 219.

- Van Opstall, Margaretha Elizabeth (1972). De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azië 1607–1612 [The journey of Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff's fleet to Asia 1607–1612]. Utrecht University.

- Bown, Stephen R. (2009). Merchant kings: when companies ruled the world, 1600–1900. New York: Thomas Dunne Books (published 2010). ISBN 9780312616113.

- Worrall, Simon (23 June 2012). "The world's oldest clove tree". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Unoki, Ko (2013). Mergers, Acquisitions and Global Empires: Tolerance, Diversity and the Success of M&A. Oxon: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 9781136215384.

- Krondl, Michael (2008). The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. Random House Publishing Group. p. 209. ISBN 9780345509826.

- Raden, Aja (2015). Stoned: Jewelry, Obsession, and How Desire Shapes the World. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062334718.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9780300105186.

- "Frigates, War Canoes, and Volcanoes". 26 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Turner, Jack (10 December 2008). Spice: The History of a Temptation. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 290–291. ISBN 9780307491220.

- Prak, Maarten; Webb, Diane (22 September 2005). The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century: The Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780521843522.

- Milton, Giles (12 April 2012). Nathaniel's Nutmeg. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 163. ISBN 9781444717716.

- Loth., Vincent C. (1995). "Pioneers and Perkeniers: The Banda Islands in the 18th Century". Cakalele. 6: 13–35. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Vol. 1, Part 2: From c. 1500 to c. 1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780521663700.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Vol. 1: From Early Times to c. 1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 430. ISBN 9780521355056.

- Brown, Iem (2004). The Territories of Indonesia. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 9781135355418.

- Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (2008). The War for All the Oceans: From Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo. Penguin. pp. 344–355. ISBN 978-0-14-311392-8.

- "Sir Christopher Cole, K.C.B.". The Annual biography and obituary. Vol. 21. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown. 1837. pp. 114–123.

- Milne, Peter (16 January 2011). "Banda, the nutmeg treasure islands". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

But the economic importance of the Bandas was only fleeting. With the Napoleonic wars raging across Europe, the English returned to the Bandas in the early 19th century, temporarily taking over control from the Dutch. This gave the English an opportunity to uproot hundreds of valuable nutmeg seedlings and transport them to their own colonies in Ceylon and Singapore, breaking forever the Dutch monopoly and consigning the Bandas to economic decline and irrelevance.

- Witton, Patrick; Elliott, Mark; Greenway, Paul; Jealous, Virginia (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781740591546.

- Winn, Phillip (2010). "Slavery and cultural creativity in the Banda Islands". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 41 (3): 365–389. doi:10.1017/s0022463410000238.

General references

- Lape, Peter (2000). "Political dynamics and religious change in the late pre-colonial Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia". World Archaeology. 32 (1): 138–155. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.500.4009. doi:10.1080/004382400409934. S2CID 19503031.

- Muller, Karl (1997). Pickell, David (ed.). Maluku: Indonesian Spice Islands. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 978-962-593-176-0.

- Villiers, John (1981). "Trade and society in the Banda Islands in the sixteenth century". Modern Asian Studies. 15 (4): 723–750. doi:10.1017/s0026749x0000874x.

- Warburg, Otto (1897) Die Muskatnuss: ihre Geschichte, Botanik, Kultur, Handel und Verwerthung sowie ihre Verfälschungen und Surrogate zugleich ein Beitrag zur Kulturgeschichte der Banda-Inseln. Leipzig: Engelmann.

- Winn, Phillip (1998). "Banda is the Blessed Land: sacred practice and identity in the Banda Islands, Maluku". Antropologi Indonesia. 57: 71–80.

- Winn, Phillip (2001). "Graves, groves and gardens: place and identity in central Maluku, Indonesia". The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. 2 (1): 24–44. doi:10.1080/14442210110001706025. S2CID 161495500.

- Winn, Phillip (2002). "Everyone searches, everyone finds: moral discourse and resource use in an Indonesian Muslim community". Oceania. 72 (4): 275–292. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.2002.tb02796.x.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Capture of Banda Neira by the British Royal Navy 1810

- "Banda Sea Islands moist deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Forts of the Spice Islands