Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet

Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet (2 June 1768 – 25 September 1843)[1] was a British Whig politician, Lord Mayor of London from 1815 to 1817, and from 1817 until his death in 1843 a reformist Member of Parliament.

Matthew Wood | |

|---|---|

Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet, wearing the chain of the Lord Mayor of London. Portrait by Arthur William Devis | |

| Lord Mayor of London | |

| In office 1815–1817 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Birch |

| Succeeded by | Christopher Smith |

| Member of Parliament for the City of London | |

| In office June 1817 – 25 September 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Harvey Christian Combe |

| Succeeded by | James Pattison |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Matthew Wood 2 June 1768 Tiverton, Devon |

| Died | 25 September 1843 London, United Kingdom |

| Spouse | Maria Page |

| Children | 6 |

Early life

Matthew Wood was the son of William Wood (died 1809), a serge maker from Exeter and Tiverton both in Devon, by his wife Catherine Cluse (died 1798).[2] He was descended from the Wood family of Hareston[3] in the parish of Brixton in Devon, which the family had inherited by marriage to the heiress of the Carslake family.[4]

Business career

Wood was educated briefly at Blundell's School in Tiverton, before being obliged to help his ailing father. He was involved in the putting-out system of his father's business for serge, based at Tiverton, and the sale of cloth in Exeter.[5] Wood was then apprenticed to his cousin, an Exeter chemist and druggist, but moved to London in 1790 to set himself up in business.[6]

In 1797 Wood took an opportunity to go into business as a hop merchant.[7] From then on he was involved in parallel developments, as a druggist and hop trader.

Around 1804 Wood went into business, on the hops side, with Lieut.-Col. Edward Wigan, who died in 1814, a London militia officer and goldsmith. He was later partner with Edward Wigan, eldest son of Lieut. Col. Edward Wigan.[8][9] The firm of Wood, Wigan & Wood was based in Falcon Square, a small and largely residential area between Falcon Street to the west, and Silver Street to the east.[10] The partners in it, in 1816, were Matthew Wood, Alfred Wood (another son of Lieut.-Col. Edward Wigan), and Philip Western Wood, Matthew's brother.[9] Around 1820 that part of the business was moved to St Margaret Hill, in the centre of Southwark. The partnership changed, with the Wigans dropping out. Philip Wood, another brother Benjamin Wood, and Matthew's youngest son Western all coming in. In 1832 the business was once more in the City of London, on Mark Lane. It traded as Wood, Field & Wood.[11]

Wood also carried on a druggist business, in Falcon Square.[12]

In politics

Wood was elected to the Court of Common Council of the City of London, representing the Cripplegate ward, in 1802, holding the seat to 1807. In 1807 he was elected to the Court of Aldermen.[1] His initial effort to get into parliament was at the 1812 general election, when he and Robert Waithman only split the radical vote, coming 6th and 5th respectively in the four-member City of London constituency.[13] In an 1814 by-election at Grampound he showed an interest, but did not make it a serious contest.[14]

Wood was a member of the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers, by tradition the leading Whig livery company;[15][16] he became its Prime Warden. He served as Sheriff of the City of London for 1809.[17] He won popularity by encouraging resistance to unpopular government measures and by his vigour as first magistrate in seeking to suppress the London underworld.[1]

Wood was a founder member of the Hampden Clubs and of the Union Society for parliamentary reform in 1812. This was under the aegis of John Cartwright, whose parliamentary election campaign he supported in 1814.[1]

Lord Mayor

Wood was Lord Mayor of London from 1815 to 1817.[17] In December 1816, he dispersed the Spa Fields riot, but went on to present to the Prince Regent a petition expressing the rioters demands for popular representation and reform.[1]

Member of Parliament

On 17 January 1817 Wood and Robert Waithman gave a reform banquet. At it Wood spoke in favour of triennial parliaments.[18]

In June 1817, Wood was elected unopposed[19] as a Member of Parliament for the City of London, following the resignation of Harvey Christian Combe MP.[15] He held the seat until his death in 1843.[20]

In 1821, Matthew Wood was one of "seven wise men" that John Cartwright proposed to Jeremy Bentham act as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", their reports and observations to concern "the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom". In addition to Bentham and himself, the other names Cartwright proposed were Sir Francis Burdett, Rev. William Draper; George Ensor, Rev. Richard Hayes and Robert Williams. [21]

Caroline of Brunswick

Wood was a prominent partisan and adviser of Queen Caroline on her return to England in 1820: she arrived at Dover on 5 June.[22] In 1813, when she was a beleaguered Princess of Wales, he had gone to Kensington Palace with an address from the City of London, and congratulated her "upon her triumph over a wicked conspiracy against her honour and her life".[1] Wood had carried out a protracted campaign to stage manage her return. An apparent attempt via his son William to contact her in Italy, near Parma, took place in 1819.[23] Wood was corresponding with her by April 1820, and his son John met her in Geneva. Wood himself went to France at the end of May. At Saint-Omer, he frustrated the efforts of Henry Brougham, the Queen's attorney-general, and Lord Hutchinson, who were on a government-backed mission to buy her off. Wood convinced the Queen with promises of the popular acclaim that would greet her. They arrived in London on 6 June.[11] The diarist Charles Greville noted on 7 June:

The Queen arrived in London yesterday at seven o'clock… She travelled in an open landau, Alderman Wood sitting by her side and Lady Anne Hamilton and another woman opposite. Everybody was disgusted at the vulgarity of Wood in sitting in the place of honour, while the Duke of Hamilton’s sister was sitting backwards in the carriage.[24]

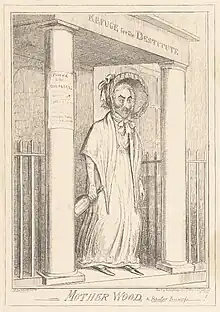

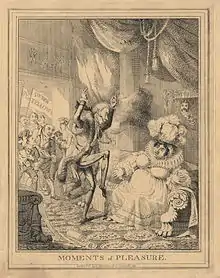

Wood took a significant role in the political uproar that followed. He avoided, however, her trial.[11] He was the subject, along with the Queen and her Italian lover Bartolomeo Pergami, of many lampoons. Theodore Lane created a series of scurrilous images of the trio. In Moments of Pleasure, Wood is seen dancing for the Queen.

At the Queen's funeral in London on 14 August 1821, Wood's son John, her chaplain, was in one of the main mourning coaches; his father Matthew's carriage was further back in the procession.[25] That night the Queen's coffin lay in St Peter's Church, Colchester. Wood attended, bringing under his coat an engraved plate, made with the agreement of the Queen's executors, Stephen Lushington and Thomas Wilde. They wished to have it attached to the coffin, but when a cabinet-maker came, Sir George Nayler, Clarenceux King of Arms would not allow it. Lushington was unable to resolve the stand-off, and a crowd gathered outside the church. In the end the plate was replaced by another, inscribed in Latin.[26]

On 15 August 1821, the Queen's coffin was taken to Harwich, and put on board HMS Glasgow. It arrived at Stade on 20 August, and ultimately was placed in a vault in Brunswick Cathedral.[27] Supporters had managed while the coffin was at sea to place on it the inscription "Caroline, the injured Queen of England".[28] Accompanying it was the Rev. John Page Wood, who had been at the Queen's deathbed.[29]

Jemmy Wood legal case

In 1836 the Gloucester banker James 'Jemmy' Wood, one of the richest men in the country, died, and Matthew Wood, though unrelated, was one of his executors and heirs. Jemmy Wood's sister Elizabeth was an admirer of Queen Caroline and had already left property to Matthew Wood when she died c.1823.[29] In 1833, Jemmy Wood gave Matthew Wood rent-free use of Hatherley House, owned by his bank had acquired; Matthew Wood in turn allowed Jemmy to send all his mail under parliamentary franked cover. Matthew Wood campaigned for a baronetcy both for himself, and for Jemmy Wood; and was written into Jemmy Wood's will.

In a resulting legal case, on 20 February 1839 Judge Herbert Jenner-Fust at the Arches Prerogative Court, London, "decided that the terms were made by conspiracy and fraud, and ordered that the whole of the immense property should be divided amongst two relations". Some years later, this verdict was overturned on appeal by Lord Lyndhurst. The remaining estate of Jemmy Wood went according to the original will, with Matthew Wood receiving over £100,000.[29]

Baronetcy

Queen Victoria made Wood a baronet in her accession year of 1837, of Hatherley House in Gloucestershire,[30] the seat being the still-disputed country house.[2]

Marriage and children

On 5 November 1795 Wood married Maria Page, the daughter of John Page of Woodbridge in Suffolk,[2] by whom he had six children:

- John Page Wood (1796–1866), who became a Church of England vicar in Essex.[2] His daughter Katharine Wood (1846–1921) is better known by her married name of Katharine O'Shea.[31] Popularly known as Kitty O'Shea, her relationship with the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell led to a political scandal which caused his downfall. John's son Evelyn Wood (1838–1919) was a Field Marshal and a recipient of the Victoria Cross.

- Maria Elizabeth Wood (born 1798)

- Catharine Wood (born 1799)

- William Wood, 1st Baron Hatherley (1801–1881), a barrister and Liberal MP who served as Lord Chancellor from 1868 to 1872

- Western Wood (1804–1863), MP for the City of London 1861–63

- Henry-Wright Wood (born 1806), died an infant.

The present Page-Wood baronets quarter the arms of Carslake Argent, a bull's head erased sable.[32]

References

- "WOOD, Matthew (1768-1843), of 77 South Audley Street, Mdx. History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- Collen, G. W. (1840). Debrett's baronetage of England. revised, corrected and continued by G.W. Collen. Vol. 3. London. p. 593.

- "Manor House Wedding Venue Devon".

- Risdon, Tristram (d.1640), Survey of Devon, 1811 edition, London, 1811, with 1810 Additions, pp.194-5

- Gentleman's Magazine, Or Monthly Intelligencer. Edward Cave. 1843. p. 541.

- "www.blundells.org - Famous OBs". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Kynaston, David (1994). The City of London: A world of its own, 1815-1890. Vol. I. Chatto & Windus. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7011-6094-4.

- The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review. Bradbury, Evans. 1854. p. 668.

- The European Magazine, and London Review. Philological Society of London. 1816.

- Baddeley, John James (1921). Cripplegate, one of the twenty-six wards of the city of London. London: Printed for private circulation. p. 133.

- "Wood, Matthew (1768-1843), of 77 South Audley Street and Little Strawberry Hill, Mdx., History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org.

- Thornbury, George Walter (1880). Old and new London: a narrative of its history, its people and its places, by W. Thornbury (E. Walford). p. 413.

- "London 1790-1820, History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org.

- "Grampound 1790-1820, History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org.

- "No. 17259". The London Gazette. 14 June 1817. p. 1339.

- Collins' Illustrated Guide to London and Neighbourhood: Being a Concise Description of the Chief Places of Interest in the Metropolis, and the Best Modes of Obtaining Access to Them : with Information Relating to Railways, Omnibuses, Steamers, &c. W. Collins. 1873. p. 96.

- "Lord Mayors of The City of London From 1189" (PDF). City of London Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Cannon, John (15 February 1973). Parliamentary Reform 1640-1832. CUP Archive. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-521-08697-4.

- Stooks Smith, Henry (1973) [1844-1850]. Craig, F. W. S. (ed.). The Parliaments of England (2nd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. pp. 211–2. ISBN 0-900178-13-2.

- Craig, F. W. S. (1989) [1977]. British parliamentary election results 1832–1885 (2nd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. p. 4. ISBN 0-900178-26-4.

- Bentham, Jeremy (1843). The Works of Jeremy Bentham: Memoirs of Bentham. London: W. Tait. pp. 522–523.

- Fraser, Flora (1996). The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline. Macmillan. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-333-57294-8.

- Fraser, Flora (1996). The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline. Macmillan. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-333-57294-8.

- Charles C. F. Greville, A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV and King William IV, volume I (London, Longmans Green & Co, 1874), at page 28

- Fraser, Flora (1996). The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline. Macmillan. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-333-57294-8.

- Fraser, Flora (1996). The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline. Macmillan. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-333-57294-8.

- Fraser, Flora (1996). The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline. Macmillan. pp. 464–465. ISBN 978-0-333-57294-8.

- Smith, E. A. "Caroline [Princess Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel] (1768–1821)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4722. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "No. 19558". The London Gazette. 14 November 1837. p. 2921.

- Fargnoli, A. Nicholas; Gillespie, Michael Patrick (2006). Critical companion to James Joyce: a literary reference to his life and work. New York: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 9781438108483.

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895; quartering illustrated in: Montague-Smith, P.W. (ed.), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Kelly's Directories Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, 1968, p.875