Sir Robert Cotton, 1st Baronet, of Connington

Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, 1st Baronet (22 January 1570/71 – 6 May 1631) of Conington Hall in the parish of Conington in Huntingdonshire, England,[1] was a Member of Parliament and an antiquarian who founded the Cotton library.

Sir Robert Cotton, 1st Baronet, of Connington | |

|---|---|

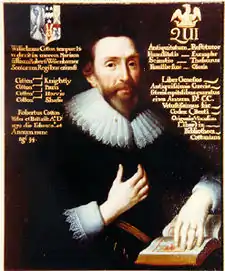

Portrait of Robert Cotton, commissioned 1626 and attributed to Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen | |

| Member of the English Parliament for Newtown | |

| In office 1601–1601 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | |

| Member of the English Parliament for Huntingdonshire | |

| In office 1604–1611 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the English Parliament for Old Sarum | |

| In office 1624–1624 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the English Parliament for Thetford | |

| In office 1625–1625 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the English Parliament for Castle Rising | |

| In office 1628–1629 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | Parliament suspended until 1640 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Bruce Cotton 22 January 1570/1 Denton, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Died | 6 May 1631 |

| Children | Sir Thomas Cotton, 2nd Baronet Roland Rowland Cotton (Saltonstall) II of Derby |

Origins

He was born on 22 January 1571 in Denton, Huntingdonshire, the son and heir of Thomas Cotton (1544–1592) of Conington (son of Thomas Cotton of Conington Sheriff of Huntingdonshire in 1547[2]) by his first wife Elizabeth Shirley, a daughter of Francis Shirley of Staunton Harold in Leicestershire.[1] The Cotton family originated at the manor of Cotton, Cheshire,[3] from which they took their surname.

Education

Cotton was educated at The King's (The Cathedral) School and Westminster School where he was a pupil of the antiquarian William Camden, under whose influence he began to study antiquarian topics. He began collecting rare manuscripts as well as collecting notes on the history of Huntingdonshire when he was seventeen.[4] He proceeded to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he graduated BA in 1585[5] and in 1589 entered the Middle Temple to study law. He began to amass a library in which the documents rivalled, then surpassed, the royal manuscript collections.

Career

Cotton was elected a Member of Parliament for Newtown, Isle of Wight in 1601 and as Knight of the Shire for Huntingdonshire in 1604.

He helped to devise the institution of the title of baronet as a means for King James I to raise funds: like a peerage, a baronetcy was heritable but, like a knighthood, it gave the holder no seat in the House of Lords.

One of his scarce monographs, Twenty-Four Arguments, proposed the bolstering of royal powers to suppress Catholic elements in England[6] in the wake of the Popery Act of 1627. His public Anti-Catholicism brought him short-lived favour with the king.

Despite this early period of goodwill with King James I, his approach to public life, based on his immersion in the study of old documents, was essentially based on that "sacred obligation of the king to put his trust in parliaments" which in 1628 was expressed in his monograph The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now Standeth, and the Remedye.

From the Court party's point of view, this was anti-royalist in nature, and the king's ministers began to fear the uses being made of Cotton's library to support pro-parliamentarian arguments. Thus it was confiscated in 1630 and returned only after his death to his heirs.

Role in Parliament

Cotton supported the claim of King James VI of Scotland to succeed Queen Elizabeth I on the English throne, and after the queen's death was commissioned to write a work defending James's claim to the throne, for which he was rewarded with a knighthood in 1603.

Cotton was elected to parliament for Huntingdonshire in 1604, a constituency previously represented by his grandfather. Cotton worked on the Committee on Grievances and in 1605–06 received the Bill pertaining to the Gunpowder Plot through his work on the Committee of Privileges. In 1607 he was reappointed to the Committee of Privileges. Cotton was appointed to the joint conference with the Lords during his work on the bill pertaining to the full union between Scotland and England in 1606–07.

In 1610, Cotton was nominated in first place to the Committee of Privileges. In 1610/11 the royal revenues were low, and Cotton wrote Means for raising the king’s estate. In this work, he suggested the formation of the baronetcy, a new higher order of social rank, higher than the knight but lower than the baron.

Cotton was not elected to the 1614 Parliament. In 1621, Cotton advised James I on the impeachment of Sir Francis Bacon concerning the respective roles of the king and Parliament. In 1624, Cotton was elected to represent Old Sarum after the previous member, Sir Arthur Ingram, decided to sit for York.[7]

He was subsequently elected to Parliament for Old Sarum (1624), Thetford (1625) and Castle Rising (1628).

The Society of Antiquaries

Cotton reunited with his former schoolmaster William Camden in the late 1580s as an early member of the Society of Antiquaries. Camden was one of the greatest early antiquarians, whose 1586 work Britannia was a chorographical (topographical and historical) survey of Britain.[8]

Cotton exerted little influence in the society until after his father's death in 1592. In 1593, he was resident at the family seat of Conington Castle, which he rebuilt. He returned to London in 1598 and revived the Society and petitioned for a permanent academy for antiquarian studies, suggesting that Cotton's collection of manuscripts be combined with the Queen's library to form a national library. The plan did not receive royal approval.[7]

The discussion of the Society in the summer of 1600 focused on ancient burial customs, probably the result of a recent visit to Hadrian's Wall by Camden and Cotton during which they collected Roman coins, monuments and fossils. The trip appears to have initiated Cotton's interest in Roman artefacts. The antiquarians Reginald Bainbridge and Lord William Howard offered Cotton Roman stones while the Essex antiquarian John Barkham arranged to send him Roman relics.[8]

Cotton's antiquarian studies influenced many people of his time and he was often looked to by other antiquarians for ideas. Below is a letter written by fellow antiquarian Roger Dodsworth to Cotton:

Honble- Sr

- With my due acknowledgement of your multiplied favours presupposed, I thought good to advertise you that, since I saw you, I have used such meanes, as my health would permitt, to enquire after such things as you desired. I have beene att Cattericke wher I was informed of 2Romaine monuments weh were found in a 1620 and are now in my Io: of Arundells keeping. I have found, a peece of a round piller, att Ribblccester, being almost half a yeard thick, and half an ell in height, with such letters, on the one side thereof, as I have figured in this paper inclosed. I saw, ther, a little table of free stone, not half a yeard square, with the portraitures of 3 armed men cutt therin, but no inscription att all theron. I saw likewise 2 other stones of the nature of slate, or thicke flaggs some yeard square, with fretted antique workes engraven on them, without any letters. I shalbe very gladd that my uttmost endeavours, might availe to requite the least of many respects you have done unto me. And do desire you to signify your pleasure, what you would have mee to doo touching the premisses, and I shall not faile to do my best in effecting thereof...

- Yours faythfully

- Roger Dodsworth

- Hutton grange 16 February 1622.[8]

The last recorded meeting of the Society of Antiquaries was in 1607.[7] Cotton, however, continued collecting.

Marriage and progeny

As a young man, Cotton may have contracted a (possibly irregular) marriage with Frideswide Faunt, daughter of William Faunt of Foston, Leicestershire, and sister of the Jesuit theologian Arthur Faunt. The marriage was recorded by William Burton, Frideswide's nephew, but is not mentioned in Cotton's own papers.[9]

In about 1593 (the precise date is not known), he married Elizabeth Brocas, the daughter of William Brocas of Theddingworth in Leicestershire. This marriage took place about a year after the death of Cotton's father, and helped to shore up his financial position, as Elizabeth was an heiress. Their subsequent marital history suggests that perhaps these factors outweighed personal compatibility.[10]

By Elizabeth, Cotton had a son: Sir Thomas Cotton, 2nd Baronet (1594–1662). Sir Thomas in turn married Margaret Howard, by whom he had a son, Sir John Cotton (born 1621).[7]

Sir Robert had an extensive circle of friends and a considerable capacity to charm, which he displayed both before and after marrying. He spent several years, and possibly more than a decade, living with the widowed Lady Hunsdon, perhaps as her lover during an overt separation from his wife. Eventually, the Cottons patched things up. Nonetheless, a reputation as something of a playboy attached to Sir Robert until the end of his life.

Library

The Cottonian Library was the richest private collection of manuscripts ever amassed.[11] Of secular libraries, it outranked the Royal Library, the collections of the Inns of Court and the College of Arms. Cotton's collection included several rare and old texts, including the original codex bound manuscript of Beowulf, written around the year 1000; the Lindisfarne Gospels, written in the seventh or eighth century; and the Codex Alexandrinus, a fifth century manuscript of the Greek Bible.[12] Cotton's house near the Palace of Westminster became the meeting-place of the Society of Antiquaries of London and of all the eminent scholars of England.[13] the Library was eventually donated to the nation by Cotton's grandson and is now housed in the British Library.[14]

The physical arrangement of Cotton's Library continues to be reflected in citations to manuscripts formerly in his possession. His library was housed in a room 26 feet (7.9 m) long by six feet wide filled with bookpresses, each surmounted by the bust of a figure from classical antiquity.[12] Counterclockwise, these were catalogued as Julius, Augustus, Cleopatra, Faustina, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. (Domitian had only one shelf, perhaps because it was over the door). Manuscripts are today designated by library, bookpress, and number: for example, the manuscript of Beowulf is designated Cotton Vitellius A.xv, and the manuscript of Pearl is Cotton Nero A.x.

Role of family on the Cotton library

Sir Robert Cotton began developing the works and manuscripts into a collection for his Library shortly after the birth of his son in 1594.[7] From the period 1609 to 1614 the deaths of various people (including Lord Lumley, Earl of Salisbury, Prince Henry, William Dethick and Northampton) all contributed to Sir Robert Cotton's purchase of works for his library.[7] Sir Robert Cotton resided in London, while his wife and son remained in the country.[7] During his father's absence Thomas Cotton studied to eventually receive his BA on 24 October 1616 from Broadgates Hall—the very same year that Sir Robert Cotton returned to his wife Elizabeth and family (a result of a hiccup with the law involving the death of earl of Somerset).[7] At that point, Sir Thomas Cotton had taken the responsibilities of the home and the library into his own hands.[7]

In 1620, Thomas Cotton married Margaret Howard with whom he had his first son, Sir John Cotton, just one year later in 1621.[7] Sir Thomas Cotton's marriage with Margaret Howard ended in 1622, which had been the year that Thomas Cotton's father, Sir Robert Cotton, permanently moved residence to The Cotton House, along with the library which remained in the Cotton House until Sir Robert Cotton's death nine years later in 1631.[7] The relocation of the library and residence to the Cotton House gave members of Parliament and government workers better access to the matter within the library to be used as resources for their work.[7]

The Cotton Library offered important and valuable sources of reference and knowledge to many people, such as John Selden, "a frequent borrower from the library, and probably its protector during the civil wars" as stated in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[7] Selden, in 1623 said of Cotton: “his kindness and willingness to make them [his collection of books and manuscripts] available to students of good literature and affairs of state".[15][7] In keeping with the notion that John Selden was a common presence in the Cotton library, The British Library holds a list of thirteen works, and the locations of those volumes today, that had been lent to Seldon by Sir Robert Cotton.[16]

After another hiccup with the government, Sir Robert Cotton was forced to close the library by Charles I because the content within the library was believed to be harmful to the interests of the Royalists in 1629.[17][7] In September 1630 Sir Robert Cotton and Sir Thomas Cotton, together, petitioned for renewed access to their library.[7] One year later, in 1631, Sir Robert Cotton died without knowing what the future held for his library, but wrote in his will that the library be left to his son Thomas Cotton and that it be passed down accordingly.[7] After the death of his father, Sir Thomas Cotton married his second wife, Alice Constable, in 1640 with whom they had their son Robert Cotton in 1644.[7] Sir Thomas Cotton's "ownership access to the Cotton library was more limited than under his father" according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Thomas Cotton maintained his ability to "protect," "improve" and "maximize the profits" received during the civil war, as he had earlier on in his life as a result of his father's absence.[7] Upon the death of Sir Robert Cotton on 13 May 1662, Sir Thomas Cotton obeyed the will of his father and passed down the library to his eldest son from his first marriage, Sir John Cotton.[7]

On 12 September 1702, Sir John Cotton died.[7] Prior to his death, Sir John Cotton had arranged for the Cotton Library to be bought for the nation of England through acts of Parliament.[7] If the library had not been sold to the nation, despite the wish of his grandfather Sir Robert Cotton, the library would have been taken over and inherited by John Cotton's two grandsons, who, unlike the rest of the college-educated Cotton family, had been illiterate and put the Cotton Library at risk of potentially getting broken up and sold to different divisions within the family.[7]

Selected manuscripts

- Cotton Julius A.x Old English Martyrology

- Cotton Augustus II.106 Magna Carta: Exemplification of 1215

- Cotton Cleopatra A.ii Life of St Modwenna

- Cotton Faustina A.x Additional Glosses to the Glossary in Ælfric's Grammar

- Cotton Tiberius B.v Labours of the Months

- Cotton Caligula A.ii "A Pistil of Susan" (frag.)

- Cotton Claudius B.iv Genesis

- Cotton Nero A.x. Pearl, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- Cotton Nero D.iv Lindisfarne Gospels

- Cotton Galba A.xviii Athelstan Psalter

- Cotton Otho C.i Ælfric's De creatore et creatura

- Cotton Vitellius A.xv Beowulf, Judith

- Cotton Vespasian D.xiv Ælfric's De duodecim abusivis

- Cotton Titus D.xxvi Ælfwine's Prayerbook

- Cotton Domitian A.viii Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (version E)

See also

References

- Kyle, Chris & Sgroi

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.242, pedigree of Cotton

- Vivian, p.240

- "Robert Cotton, 1571–1631." Robert Cotton, 1571–1631. Montague Millennium Inc., 22 February 2006. Web.

- "Cotton, Robert (Bruce) (CTN581R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Cotton, Robert (1671). Cottoni posthuma : divers choice pieces of that renowned antiquary, Sir Robert Cotton, Knight and Baronet. London: The Cotton Library. p. 107.

- Stuart, Handley (2011) [2004]. "Cotton, Sir Robert Bruce, first baronet (1571–1631)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6424. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Howarth, D. Sir Robert Cotton and the Commemoration of Famous Men. British Library

- Harris, Oliver (2008). "'The greatest blow to antiquities that ever England had': the Reformation and the antiquarian resistance". In Dijkhuizen, Jan Frans van; Todd, Richard (eds.). The Reformation Unsettled: British literature and the question of religious identity, 1560–1660. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 225–42 (228–9). ISBN 9782503526249.

- Matt, Kuhns (2014). Cotton's library: the many perils of preserving history. Lakewood, Ohio. ISBN 9780988250543. OCLC 903273973.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kesselring, K.J. (2016). The Trials of Charles 1. The Broadview Sources Series. p. 27. ISBN 9781554812912.

- Murray, Stuart A. P. (2012) [2009]. The Library: An Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 122–124. ISBN 9781616084530.

- Lee, Sidney (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Kesselring, K.J. (2016). The Trials of Charles I. The Broadview Sources Series. p. 27. ISBN 9781554812912.

- Smith, T. "Catalogue of the manuscripts in the Cottonian Library, 1696 / Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum bibliothecae Cottonianae." Ed. C. G. C. Tite (1696); repr. (1984).

- Tite, Colin G. C. (1991). "A 'loan' of printed books from Sir Robert Cotton to John Selden". Bodleian Library Record. 13 (6): 486–490.

- Kesselring, K.J. (2016). The Trial of Charles I. The Broadview Sources Series. p. 27. ISBN 9781554812912.

Further reading

- Sharpe, Kevin (1979). Sir Robert Cotton, 1586–1631: History and Politics in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019821877X.

- Tite, Colin G.C. (1994). The Manuscript Library of Sir Robert Cotton. London: British Library. ISBN 0712303596.

- Wright, C. J., ed. (1997). Sir Robert Cotton as Collector: essays on an early Stuart courtier and his legacy. London: British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-0358-3.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kyle, Chris & Sgroi, Rosemary, biography of Cotton, Sir Robert Bruce (1571-1631), of Blackfriars, London; New Exchange, The Strand; Cotton House, Westminster and Conington Hall, Hunts., published in History of Parliament: House of Commons 1604–1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 2010