Sir Robert Laurie, 6th Baronet

Admiral Sir Robert Laurie, 6th Baronet KCB (25 May 1764 – 7 January 1848) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He rose through the ranks after his entry, fighting as a lieutenant under Howe at the Glorious First of June, and being wounded in the action. Shortly after he served in the West Indies and off the American coast, where he operated successfully against enemy raiders and privateers, he was rewarded with the command of the frigate HMS Cleopatra, and in 1805 fought an action with a superior French opponent, Ville de Milan. He was forced to surrender his ship after several hours of fighting, but so heavily damaged the Frenchman that both she and the captured British vessel were taken shortly afterwards when another British frigate HMS Leander, arrived on the scene. Rewarded for his valour and honourably acquitted for the loss of his ship, he served throughout the rest of the Napoleonic Wars. He rose to flag rank after the end of the wars, eventually dying in 1848 with the rank of Admiral of the White. He inherited a baronetcy in 1804, but this became extinct upon his death.

Sir Robert Laurie | |

|---|---|

| Born | 25 May 1764 |

| Died | 7 January 1848 Maxwelton House, Dumfriesshire |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Service/ | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1780–1848 |

| Rank | Admiral of the White |

| Commands held | HMS Zephyr HMS Andromache HMS Cleopatra HMS Milan HMS Ajax |

| Battles/wars | Glorious First of June |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath |

Family and early life

Robert Laurie was born on 25 May 1764, the son of Sir Robert Laurie and his wife Mary Elizabeth Ruthven.[1] He entered the navy in 1780, spending 10 years as midshipman before being promoted to lieutenant in 1790. He was a lieutenant aboard the 90-gun second rate HMS Queen and fought in the Glorious First of June in 1794, during which action he was wounded.[1]

Command

He received a promotion in June the following year, rising to the rank of commander and being given the sloop HMS Zephyr. He served in the North Sea before being ordered to the Leeward Islands towards the end of 1796.[1] While sailing there he came across the 12-gun privateer Refléche and captured her on 8 January 1797.[2] He went on to take part in the reduction of Trinidad in February 1797, making several other captures of privateers during the rest of the year; the 4-gun Vengeur des Français on 16 June, the 6-gun Légère on 6 July and the 2-gun Va-Tout on 8 July.[2] On 17 July 1798 Laurie received a promotion to post-captain.[1]

He was removed into HMS Andromache in 1799 and spent the next several years serving on the North American and Jamaica stations. He took a Spanish gunboat off Cuba on 22 March 1801 in company with the 32-gun HMS Cleopatra, and after a spell in the Bahamas in 1803, returned to the English Channel in 1804.[3] Laurie then transferred to take command of the Cleopatra in summer 1804.[1] Laurie succeeded to the baronetcy on 10 September 1804 with the death of his father, the fifth baronet.[1] Cleopatra spent some time in the West Indies, and was homeward bound in February 1805.[4]

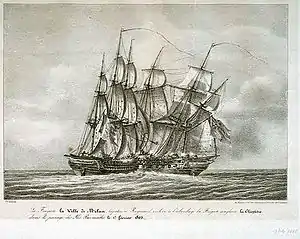

Fighting the Ville de Milan

While sailing off Bermuda on 16 February Cleopatra sighted a sail; this was the 40-gun French frigate Ville de Milan which had sailed from Martinique on 28 January under Captain Jean-Marie Renaud, bound for France with important despatches.[5] Despite identifying his quarry as a superior opponent, Laurie ordered a chase. Renaud had orders to avoid combat and pressed on sail to escape Laurie.[5] The chase covered 180 miles and lasted until the following morning, when Renaud reluctantly came about to meet the Cleopatra, which was overhauling the Ville de Milan.[6] The engagement began in earnest at 2.30pm, and a heavy cannonade was maintained between the two frigates until 5pm, when the Cleopatra had her wheel shot away and her rudder jammed.[6] The Ville de Milan approached from windward and ran aboard the Cleopatra, jamming her bowsprit over the quarterdeck of the British ship and raked her decks with musket fire. The British resisted one attempt to board, but on being unable to break free, were forced to surrender to a second boarding party.[7] The Cleopatra had 22 killed and 36 wounded, with the loss of her foremast, mainmast and bowsprit.[8] The Ville de Milan had probably about 30 killed and wounded, with Captain Renaud among the dead. She also lost her mainmast and mizzenmast.[7] Three days were spent transferring a prize crew and prisoners, and patching up the ships, before the two got underway on 21 February.[7]

However, on 23 February they were discovered by the 50-gun HMS Leander, under Captain John Talbot. Leander ran up to them, whereupon they separated. Talbot chased Cleopatra, brought her to with a shot and took possession. The freed crew reported the situation to Talbot, and left him to pursue the fleeing Ville de Milan. Talbot soon overtook her and she surrendered without a fight.[8][9][10] Laurie took back command of the Cleopatra and all three ships sailed to Halifax, where the Ville de Milan was taken into service as HMS Milan.[10][11] Laurie's engagement with the superior opponent had initially cost him his ship, but had rendered her easy prey to any other Royal Navy frigate in the vicinity.[10] Had he not brought her to battle, the Ville de Milan could have easily outsailed the Leander or even engaged her on fairly equal terms. Instead the damage and losses incurred in breaking down the Cleopatra had left her helpless to resist.[7]

A court-martial honourably acquitted Laurie of any blame for the loss of his ship, and the Patriotic Fund presented him with a 100-guinea sword 'as a well-merited compliment to his great bravery and skill'.[11][12] Laurie was duly appointed to command the Milan.[10] He was then appointed to command the 74-gun third rate HMS Ajax towards the end of 1811, and spent the rest of the war in the Mediterranean.[1]

Later life

Laurie was promoted to Rear-Admiral of the Blue on 19 July 1821,[13] Rear-Admiral of the White 27 May 1825,[14] Rear-Admiral of the Red 22 July 1830,[15] Vice-Admiral of the White 10 January 1837,[16] Vice-Admiral of the Red (date unknown) and Admiral of the Blue on 9 November 1846.[17][1][18] He was nominated a Knight Commander of the Bath in 1836.[19] He died unmarried with the rank of Admiral of the White on 7 January 1848 at his seat of Maxwelton House, Dumfriesshire.[1] He had no issue, and the baronetcy became extinct upon his death.[1] Maxwelton House later passed to his grand-nephew Sir Emilius Bayley who changed his name and baronetcy to Laurie.

Notes

- The Gentleman's Magazine. p. 434.

- Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 274.

- Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 183.

- Henderson. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. p. 81.

- Henderson. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. p. 82.

- Henderson. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. p. 83.

- Henderson. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. p. 84.

- Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail. p. 206.

- Colledge. Ships of the Royal Navy. p. 71.

- Henderson. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. p. 85.

- Brenton. The Naval History of Great Britain. p. 98.

- Allen. Battles of the British Navy. p. 100.

- "No. 17727". The London Gazette. 20 July 1821. p. 1512.

- "No. 18141". The London Gazette. 28 May 1825. p. 933.

- "No. 18709". The London Gazette. 23 July 1830. p. 1540.

- "No. 19456". The London Gazette. 10 January 1937. p. 70.

- "No. 20660". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 November 1846. p. 3994.

- United Service Magazine. p. 154.

- "No. 18850". The London Gazette. 13 September 1831. p. 1893.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 2. Henry G. Bohn.

- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1837). The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Year MDCCLXXXIII. to MDCCCXXXVI. Vol. 2. H. Colburn.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Henderson, James (2005) [1975]. Frigates, Sloops and Brigs: An Account of the Lesser Warships of the Wars from 1793 to 1815. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-301-0.

- Nichols, John (1848). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 183. E. Cave.

- Nichols, John (1847). The United Service Magazine. Vol. 3. H. Colburn.

- O'Byrne, William Richard (1849). . . John Murray – via Wikisource.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-295-5.