Sir Thomas Herbert, 1st Baronet

Sir Thomas Herbert, 1st Baronet (1606–1682), was an English traveller, historian and a gentleman of the bedchamber of King Charles I while Charles was in the custody of Parliament (from 1647 until the king's execution in January 1649).[1]

Biography

Herbert was born to a Yorkshire family.[1] His birthplace, a timber-framed structure, still stands in York and is known as the Herbert House.[2] Several of Herbert's ancestors were aldermen and merchants in that area – such as his grandfather and benefactor, Alderman Herbert (d. 1614) – and they traced a connection with the Earls of Pembroke.[3] After attending St Peter's School, York and Tonbridge School, he is said to have studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Jesus College, Oxford (1621),[3][4] but afterwards removed to Cambridge, through the influence of his uncle Dr Ambrose Akroyd.[3]

In 1627 William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, procured his appointment in the suite of Sir Dodmore Cotton, then starting as ambassador for Persia with Sir Robert Shirley. Sailing in March they visited the Cape, Madagascar, Goa and Surat; landing at Gambrun on the Persian coast (10 January 1628), they travelled inland to Ashraf and thence to Qazvin, where both Cotton and Shirley died, and whence Herbert made extensive travels in the Persian hinterland, visiting Kashan, Baghdad and Amol. On his return voyage Herbert touched at Ceylon, the Coromandel coast, Mauritius and St Helena. He reached England in 1629, travelled in Europe in 1630–1631, married in 1632 and retired from court in 1634 (his prospects perhaps blighted by Pembroke's death in 1630); after this he resided on his Tintern estate and elsewhere until the English Civil War, when he sided with Parliament.[3] He later published an account of his travels.

He was gentleman of the bedchamber to King Charles I from 1647 up to the king's execution. During the first civil war he was a keen supporter of Parliament, and when he was in the king's service the New Model Army found no reason to suspect him of disloyalty.[5]

There is varied opinion on the matter of Herbert's devotion to King Charles. In 1678 he published Threnodia Carolina, an account of the last two years of the king's life. In this account Herbert seems devoted in the extreme, being too distraught to be with the king on the scaffold and bursting into tears when the king seemed upset by some news he had brought. It is true that many of the staunch Roundheads Parliament appointed to the king's service were converted into royalists on getting to know him. However Threnodia Carolina may have been an attempt to give Herbert a good name in Charles II's government (the king made him a baronet) and to clear the name of his son-in-law Robert Phayre, who was a regicide.[5]

After the execution Herbert followed the New Model Army to Ireland arriving that summer to take up a position as a parliamentary commissioner. He was to remain in Ireland during the following decade serving in various governmental offices. In December 1653 he was appointed secretary to the Governing Commission for Ireland, which was redesigned in the August 1654 the Governing Council of Ireland. He served as its Clerk until 1659. Henry Cromwell knighted him for his services in July 1658. At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 Herbert returned to London to take advantage of the offer of a general pardon. On 3 July 1660, shortly after his arrival in England, he had an audience with King Charles II who created him a baronet (his previous Cromwellian knighthood having passed into oblivion at the restoration).[5] After this Herbert dropped out of public life, but initially he remained in London residing in York Street, Westminster, until the Great Plague in 1666, when he retired to York, where he died (at Petergate House) on 1 March 1682,[3] and was buried in the church of St. Crux in that city, where his widow placed a brass tablet to his memory.Rigg 1891, p. 216

Works

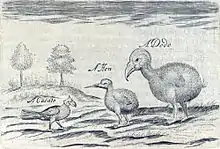

Herbert's chief work is the Description of the Persian Monarchy now beinge' the Orientall Indyes, Iles and other ports of the Greater Asia and Africk (1634), reissued with additions, &c., in 1638 as Some Yeares Travels into Africa and Asia the Great (al. into divers parts of Asia and Afrigue), a third edition followed in 1664, and a fourth in 1677. This is one of the best records of 17th-century travel. Among its illustrations are remarkable sketches of the dodo, cuneiform inscriptions and Persepolis.[3]

Herbert's Threnodia Carolina; or, Memoirs of the two last years of the reign of that unparallell'd prince of ever blessed memory King Charles I., was in great part printed at the author's request in Wood's Athenae Oxonienses, in full by Dr C Goodall in his Collection of Tracts (1702, repr. G. & W. Nicol, 1813).[3]

Sir William Dugdale is understood to have received assistance from Herbert in the Monasticon Anglicanum, vol. iv.; see two of Herbert's papers on St John's, Beverley and Ripon collegiate church, now cathedral, in Drake's Eboracum (appendix). Cf. also Robert Davies account of Herbert in The Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Journal, part ni., pp. 182–214 (1870), containing a facsimile of the inscription on Herbert's tomb; Wood's Athenae, iv. I5-41; and Fasti, 11. 26, 131, 138, 143–144, 150.[3]

Family

Herbert married, on 16 April 1632, Lucia, daughter of Sir Walter Alexander, Gentleman Usher to Charles I. She died in 1671. They had four sons and six daughters, but only one son and three daughters survived their father:[5][6]

- Henry (d. 1687), who succeed his father as baronet Herbert of Tintern.[7]

- Elizabeth, who married Colonel Robert Phaire of Cork on 16 August 1658.[5]

- Lucie.

- Anne.

Within a year of Lucia's death Herbert married Elizabeth (d. 1696), daughter of Gervase Cutler, of Stainbrough, Yorkshire and Magdalen Egerton, and niece of the Earl of Bridgewater. They had one child, a daughter, who died in infancy.[5][6]

Notes

- Cousin 1910.

- "York Conservation Trust | Properties | Sir Thomas Herbert's House". www.yorkconservationtrust.org. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 340.

- "Herbert, Thomas (HRBT621T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Fritze 2004.

- Rigg 1891, p. 216.

- Rigg 1891, p. 216 cites Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1661–2, p. 290; Wotton, Baronetage, iv. 276.

References

- Rigg, James McMullen (1891). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 26. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 215–217.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2004). "Herbert, Sir Thomas, first baronet (1606–1682)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13049. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Herbert, Sir Thomas". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Herbert, Sir Thomas". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Herbert, Sir Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 340.

Further reading

- Herbert, Sir Thomas (1815), Memoirs of the two last years of the reign of king Charles (3 ed.), G. and W. Nicol

- Leigh Rayment's list of baronets – Baronetcies beginning with "H" (part 2) "Herbert of Tintern, Monmouth"