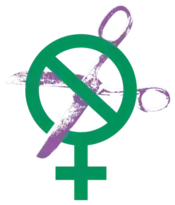

Sisters Uncut

Sisters Uncut is a British feminist direct action group that is opposed to cuts to UK government services for domestic violence victims.[1] It was founded in November 2014, and came to international prominence in October 2015 for a protest on the red carpet at the London premiere of the film Suffragette.[2] The group identify as revolutionary feminists and police and prison abolitionists, and is open to women (including trans and intersex women), nonbinary, agender and gender variant people.[3] The group aims to organise non-hierarchically and uses consensus decision-making.[3] Sisters Uncut originated in London but has regional groups throughout the UK[4] including Manchester and Leeds.[5]

| |

| Founded | November 2014 |

|---|---|

| Type | Activist group |

| Focus | Anti-austerity, Feminism, Intersectionality, Domestic violence, Trans feminism, Black feminism, Working class feminism |

| Location | |

| Method | Demonstration, Direct action, Civil disobedience, Community work |

| Website | http://www.sistersuncut.org |

Background and founding

Under the UK Coalition government of 2010-2015, funding for domestic violence services was cut dramatically, leading to concern from groups such as the Women's Aid Federation of England that the cuts could leave victims of abuse with no ability to escape their abusers.[6] Sisters Uncut was founded in November 2014 in response to these concerns. The group was founded by women from the anti-austerity direct action group UK Uncut, and its name is a reference to that group.[7][8]

Positions

Sisters Uncut is a feminist organisation, and it engages in direct action to attain its goals.[9][1][10] They have been described as "an anti-abuse campaign group".[11][12] The organisation opposes putting undercover police in bars and clubs.[13]

Sisters Uncut takes the position that the criminalisation of prostitution puts sex workers in more danger. They also oppose the Nordic model in which only buyers of sex are prosecuted, believing that it reduces customers and income to sex workers.[14][15]

Shon Faye describes Sisters Uncut as a "feminist organisation fighting for better provision for women in domestic violence".[16]

Activism

The group has become known for high-profile direct action which highlights and challenges UK government policy that affects survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Protests by the group have included:

- A demonstration at the London Councils building on 4 May 2015 which included occupying the roof of the building to highlight the role of local councils in making cuts to domestic violence services.[17][18][19]

- A protest outside the Daily Mail headquarters in Kensington in August 2015; the group burned copies of the newspaper in the street to protest what they described as"anti-migrant propaganda".[20] The paper had called for British troops to be sent to Calais refugee camps to stop migrants reaching the UK.[21]

- Protests outside Yarl's Wood Immigration Removal Centre to demand an end to immigration detention and an end to abuse of migrant women that takes place inside of them.[22]

- A high-profile protest at the 7 October 2015 London premiere of the 2015 film Suffragette against cuts to domestic violence services.[23][24] Their tagline was "Dead women can't vote". The film's star Helena Bonham-Carter described the protest as "perfect.. If you feel strongly enough about something and there's an injustice there you can speak out and try to get something changed". Carey Mulligan, another actress who performed in the film, said that the protest was "awesome" and that she was sad she had missed it.[25]

- Dying the fountains in Trafalgar Square red to symbolism the blood of women who are murdered at the hands of abusive partners, in an action timed to coincident with the 2015 Autumn Budget.[26]

- Protests against cuts to local domestic violence services, including a protest in a Portsmouth Council meeting where the group disrupted the meeting by releasing 4,745 pieces of confetti to symbolise the number of recorded instances of domestic violence in Portsmouth in 2014.[27] This was to protest a planned £180,000 of cuts to domestic violence services by the council.[28] This protest led to one arrest.

- Taking over an empty council home in Hackney, East London from July - September 2016 to highlight the urgent need for safe and secure housing for victims of domestic violence.[29][30]

- Blocking bridges in Bristol, London, Glasgow and Liverpool to coincide with the 2016 Autumn Statement.[31] The group argued that by cutting services, the government were "blocking bridges to safety" for domestic violence victims.

- In May 2017, taking over a building on the former site of Holloway Prison, demanding that the land be used for a women's centre and social housing.[32][33]

- A protest on the red carpet at the British Academy Film and Television Arts Awards in February 2018 against the government's planned Domestic Violence and Abuse Bill, which they argued would actually harm victims by increasing criminal justice powers rather than funding support services.[34]

- The delivery of 30,000 pieces of paper which blocked the doors to the Crown Prosecution Service in Westminster, highlighting the CPS policy of frequently demanding that the police download the data from the mobile phones of sexual violence victims, a process which focuses on the investigation of victims instead of their abusers. The offices were subsequently evacuated. The action coincided with Max Hill QC's first day in post as the head of the CPS in November 2018.[35]

- Ad-Hacking London Tube posters replacing adverts with poems from women & non-binary people who have been silenced by the state. The poems share real stories of how government cuts and ‘hostile environment’ policies have left victims locked up in prison, locked out of refuges, and locked in violent relationships.[36]

- Following the death of Sarah Everard in March 2021, Sisters Uncut helped organise a number of vigils and protests, both to mourn the death and to protest against violence against women, specifically by the police force.[37][38]

- The group opposes the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.[8][9]

- The group was central to the early organising within the Kill the Bill movement.

- In the later months of 2021, Sisters Uncut announced the launch of the national CopWatch Network: an abolitionist network of police intervention groups.[39]

- In March 2022, to mark the one year anniversary of the Clapham Common Vigil, Sisters Uncut set off 1000 rape alarms outside Charing Cross police station in protest of police violence against women. They demanded the public withdraw consent from British policing.[40]

References

- "London Police's Treatment of Women at a Vigil Prompted Fury. Campaigners Say a Reckoning Is Overdue". Time Magazine. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "'Why I stormed the red carpet at the premiere of the Suffragette film' - BBC Newsbeat". BBC Newsbeat. 10 July 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Sisters Uncut: FAQs". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Sisters Uncut: Meetings". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Intersectional Feminism in Action: Sisters Uncut Leeds : Centre for Interdisciplinary Gender Studies". gender-studies.leeds.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "SOS Data Report - Womens Aid". Women's Aid. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Guest blog: Sisters Uncut 23 October 2014 UK Uncut blog Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Taub, Amanda (21 March 2021). "After Sarah Everard's Killing, Women's Groups Want Change, Not More Policing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "The Solution to Violence Against Women Will Never Be 'More Police'". Vice News. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Heurts à Londres lors d'un hommage à Sarah Everard, victime d'un féminicide". France 24 (in French). 14 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Elks, Sonia (13 March 2021). "Women vow to defy ban on vigils for Sarah Everard in UK murder case". Reuters. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Britain's Kate, Duchess of Cambridge, mingles with people mourning murder victim Sarah Everard". The Straits Times. 14 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Anger over plans for plainclothes police officers to patrol bars and clubs to safeguard women from predatory men". The Independent. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Why Not The Nordic Model?". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- Bartosch, Josephine (16 March 2021). "For the Sisters or the Misters?". The Critic. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- Faye, Shon (21 November 2017). "Trans women need access to rape and domestic violence services. Here's why". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Rucki, Alexandra Feminists occupy roof of London Councils building and set off smoke flares to highlight cuts to domestic violence services 4 May 2015 Evening Standard Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Boland, Stephanie Anti-austerity women shut down a London street 4 May 2015 New Statesman Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Richardson Andrew, Charlotte A refuge provided safety for me and my family, others are not so lucky now 7 May 2015 The Guardian Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Hutchins, Liz Burning the Daily Mail with Sisters Uncut 3 August 2015 Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Ramiro, Joana Shocked Paper's Jitters As Protest Burns Mail Copies 3 August 2015 Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Morning Star Retrieved 8 October 2015

- McGuirk, Siobhan Video report: Shut down Yarl's Wood! August 2015 Red Pepper Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Warren, Rossalyn Women Stormed The "Suffragette" Movie Premiere Saying The Feminist Struggle Isn't Over 8 October 2015 BuzzFeed Retrieved 8 October 2015

- "Why did Sisters Uncut protest at the premiere of Suffragette?". The Guardian. 9 October 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Gander, Kashmira & Townsend, Megan Suffragette premiere: Protesters lie on red carpet in demonstration against cuts to domestic violence services 7 October 2015 The Independent Retrieved 8 October 2015

- Gayle, Damien (28 November 2015). "Trafalgar Square runs red with 'blood' in domestic violence cuts protest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Portsmouth budget protest". ITV News. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Sisters Uncut 'shut down' a council meeting where members were discussing £180,000 of cuts to domestic violence services". The Independent. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Feminists 'Reclaim' Council Flat In Protest Over Cuts To Domestic Violence Services". HuffPost UK. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Bartholomew, Emma (14 July 2016). "Sisters Uncut occupies empty council flat in Hackney to highlight domestic abuse aid cuts". Hackney Gazette. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- Persio, Sofia Lotto (20 November 2016). "Sisters Uncut block bridges across the UK to protest cuts to domestic violence services". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Sisters Uncut occupy old women's prison to stop it being turned into luxury flats". Metro. 28 May 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "We at Sisters Uncut have occupied Holloway prison. Why? Domestic violence | Nandini Archer". The Guardian. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- Mumford, Gwilym (18 February 2018). "Domestic violence activists Sisters Uncut invade Baftas red carpet". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Sisters Uncut: Survivors of sexual violence need #supportnotsuspicion". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Sisters Uncut: PRESS RELEASE: Sisters Uncut hack tube poems to amplify voices silenced by the state". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Sisters Uncut: Why we gathered at Clapham Common, even when we were told not to". Sisters Uncut. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- Sinclair, Leah (15 March 2021). "Police guard Churchill statue as protesters descend on Westminster". The Evening Standard. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- "Find your local CopWatch group". Netpol. 6 April 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- "Protesters at demo against 'rotten' Met activate rape alarms at police station". The Independent (UK). Retrieved 23 November 2022.