Snow White

"Snow White" is a German fairy tale, first written down in the early 19th century. The Brothers Grimm published it in 1812 in the first edition of their collection Grimms' Fairy Tales, numbered as Tale 53. The original German title was Sneewittchen; the modern spelling is Schneewittchen. The Grimms completed their final revision of the story in 1854, which can be found in the 1857 version of Grimms' Fairy Tales.[1][2]

| Snow White | |

|---|---|

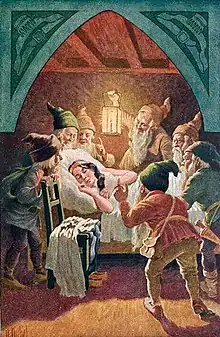

Schneewittchen by Alexander Zick | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Snow White |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | 709 |

| Country | Germany |

The fairy tale features such elements as the magic mirror, the poisoned apple, the glass coffin, and the characters of the Evil Queen and the seven Dwarfs. The seven dwarfs were first given individual names in the 1912 Broadway play Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and then given different names in Walt Disney's 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The Grimm story, which is commonly referred to as "Snow White",[3] should not be confused with the story of "Snow-White and Rose-Red" (in German "Schneeweißchen und Rosenrot"), another fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm.

In the Aarne–Thompson folklore classification, tales of this kind are grouped together as type 709, Snow White. Others of this kind include "Bella Venezia", "Myrsina", "Nourie Hadig", "Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree",[4] "The Young Slave", and "La petite Toute-Belle".

Plot

At the beginning of the story, a queen sits sewing at an open window during a winter snowfall when she pricks her finger with her needle, causing three drops of red blood to drip onto the freshly fallen white snow on the black windowsill. Then she says to herself, "How I wish that I had a daughter that had skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood and hair as black as ebony." Some time later, the queen dies giving birth to a baby daughter whom she names Snow White. (However, in the 1812 version of the tale, the queen does not die but later behaves the same way the step-mother does in later versions of the tale, including the 1854 iteration.) A year later, Snow White's father, the king, marries again. His new wife is very beautiful, but a vain and wicked woman who practices witchcraft. The new queen possesses a magic mirror, which she asks every morning, "Mirror mirror on the wall, who is the fairest one of all?" The mirror always tells the queen that she is the fairest. The queen is always pleased with that response because the magic mirror never lied. But when Snow White is seven years old, her fairness surpasses that of her stepmother. When the queen again asks her mirror the same question, it tells her that Snow White is the fairest.[1][5]

This gives the queen a great shock. She becomes envious, and from that moment on, her heart turns against Snow White, whom the queen grows to hate increasingly with time. Eventually, she orders a huntsman to take Snow White into the forest and kill her. As proof that Snow White is dead, the queen also wants him to return with her heart, which she will consume in order to become immortal. The huntsman takes Snow White into the forest, but after raising his dagger, he finds himself unable to kill her. When Snow White learns of her stepmother's evil plan she tearfully begs the huntsman, "Spare me this mockery of justice! I will run away into the forest and never come home again!" After seeing the tears in the princess's eyes, the huntsman reluctantly agrees to spare Snow White and brings the queen a boar's heart instead.[1][5]

After wandering through the forest for hours, Snow White discovers a tiny cottage belonging to a group of seven dwarfs. Since no one is at home, she eats some of the tiny meals, drinks some of their wine, and then tests all the beds. Finally, the last bed is comfortable enough for her, and she falls asleep. When the dwarfs return home, they immediately become aware that there has been a burglar in their house, because everything in their home is in disorder. Prowling about frantically, they head upstairs and discover the sleeping Snow White. She wakes up and explains to them about her stepmother's attempt to kill her, and the dwarfs take pity on her and let her stay with them in exchange for a job as a housemaid. They warn her to be careful when alone at home and to let no one in while they are working in the mountains.[1][5]

Snow White grows into an absolutely lovely, fair and beautiful young maiden. Meanwhile, the queen, who believes she got rid of Snow White a decade earlier, asks her mirror once again: "Mirror mirror on the wall, who now is the fairest one of all?" The mirror tells her that not only is Snow White still the fairest in the land, but she is also currently hiding with the dwarfs.[1] The queen is furious and decides to kill the girl herself. First, she appears at the dwarfs' cottage, disguised as an old peddler, and offers Snow White a colourful, silky laced bodices as a present. The queen laces her up so tightly that Snow White faints; the dwarfs return just in time to revive Snow White by loosening the laces. Next, the queen dresses up as a comb seller and convinces Snow White to take a beautiful comb as a present; she strokes Snow White's hair with the poisoned comb. The girl is overcome by the poison from the comb, but is again revived by the dwarfs when they remove the comb from her hair. Finally, the queen disguises herself as a farmer's wife and offers Snow White a poisoned apple. Snow White is hesitant to accept it, so the queen cuts the apple in half, eating the white (harmless) half and giving the red poisoned half to Snow White; the girl eagerly takes a bite and then falls into a coma, causing the Queen to think she has finally triumphed. This time, the dwarfs are unable to revive Snow White, and, assuming that the queen has finally killed her, they place her in a glass casket as a funeral for her.[1][5]

The next day, a prince stumbles upon a seemingly dead Snow White lying in her glass coffin during a hunting trip. After hearing her story from the Seven Dwarfs, the prince is allowed to take Snow White to her proper resting place back at her father's castle. All of a sudden, while Snow White is being transported, one of the prince's servants trips and loses his balance. This dislodges the piece of the poisoned apple from Snow White's throat, magically reviving her.[6] The Prince is overjoyed with this miracle, and he declares his love for the now alive and well Snow White, who, surprised to meet him face to face, humbly accepts his marriage proposal. The prince invites everyone in the land to their wedding, except for Snow White's stepmother.

The queen, believing herself finally to be rid of Snow White, asks again her magic mirror who is the fairest in the land. The mirror says that there is a bride of a prince, who is yet fairer than she. The queen decides to visit the wedding and investigate. Once she arrives, the Queen becomes frozen with rage and fear when she finds out that the prince's bride is her stepdaughter, Snow White herself. The furious Queen tries to sow chaos and attempts to kill her again, but the prince recognizes her as a threat to Snow White when he learns the truth from his bride. As punishment for the attempted murder of Snow White, the prince orders the Queen to wear a pair of red-hot iron slippers and to dance in them until she drops dead. With the evil Queen finally defeated and dead, Snow White's wedding to the prince peacefully continues.

- Franz Jüttner's illustrations from Sneewittchen (1905)

1. The Queen asks the magic mirror

1. The Queen asks the magic mirror 2. Snow White in the forest

2. Snow White in the forest 3. The dwarfs find Snow White asleep

3. The dwarfs find Snow White asleep 4. The dwarfs leave Snow White in charge

4. The dwarfs leave Snow White in charge 5. The Queen visits Snow White

5. The Queen visits Snow White 6. The Queen has poisoned Snow White

6. The Queen has poisoned Snow White 7. The Prince awakens Snow White

7. The Prince awakens Snow White 8. The Queen discovers and confronts Snow White at her wedding

8. The Queen discovers and confronts Snow White at her wedding

Inspiration

Scholars have theorized about the possible origins of the tale, with folklorists such as Sigrid Schmidt, Joseph Jacobs and Christine Goldberg noting that it combines multiple motifs also found in other folktales.[7][8] Scholar Graham Anderson compares the fairy tale to the Roman legend of Chione, or "Snow," recorded in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[9][10]

In the 1980s and 1990s, some German authors suggested that the fairy tale could have been inspired by a real person. Eckhard Sander, a teacher, claimed that the inspiration was Margaretha von Waldeck, a German countess born in 1533, as well as several other women in her family.[11] Karlheinz Bartels, a pharmacist and scholar from Lohr am Main, a town in northwestern Bavaria, created a tongue-in-cheek theory that Snow White was Maria Sophia Margarethe Catharina, Baroness von und zu Erthal, born in 1725.[12][13] However, these theories are generally dismissed by serious scholars, with folklore professor Donald Haase calling them "pure speculation and not at all convincing."[14][15][16]

More convincing is that Giambattista Basile wrote and told his fairy tales well before Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, who knew and translated his fairy tales, so they also took inspiration from them. The masterpiece "Lo cunto de li cunti" published posthumously in the years 1634-1636 contains fairy tales inspired by real Italian characters, such as the case of "Lo cuorvo" or "Il corvo" ("The Raven").[17] This fairy tale tells of a noble man (with a name mistaken for real life), who one day sees a dead raven in the snow, and the contrast of red blood on white strikes him so much that he does not want anything more than a white-skinned, red-cheeked bride. Reading the story, the bride is found in Venice, where she seems to have originated from the family of the real person who inspired this tale in Basile. This is one of the first inspirations for that character, that character who will later be called Snow White in other stories. This interpretation would reconnect with that of Graham Anderson, because the real characters would be linked to the birthplace of the Latin writer Ovid Naso. Thus the story of Chione, together with the marriage of Giovanna Zazzera (of Venetian origin) with Annibale Corvi (the Corvi family adored the ravens for a legendary event of the past), gave inspiration to Basile for his tale of "The Crow" or "The Raven". Where there was precisely a woman from Venice with the characteristics required by the noble man and which correspond to the characteristics of that character who would later be called Snow White.

Variations

The principal studies of traditional Snow White variants are Ernst Böklen's, Schneewittchen Studien of 1910, which reprints fifty Snow White variants,[18] and studies by Steven Swann Jones.[19] In their first edition, the Brothers Grimm published the version they had first collected, in which the villain of the piece is Snow White's jealous biological mother. In a version sent to another folklorist prior to the first edition, additionally, she does not order a servant to take her to the woods, but takes her there herself to gather flowers and abandons her; in the first edition, this task was transferred to a servant.[20] It is believed that the change to a stepmother in later editions was to tone down the story for children.[21][22]

A popular but sanitized version of the story is the 1937 American animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by Walt Disney. Disney's variation of Snow White gave the dwarfs names and included a singing Snow White. The Disney film also is the only version in which Snow White and her prince meet before she bites the apple; in fact, it is this meeting that sets the plot in motion. Instead of her lungs and liver, as written in the original, the huntsman is asked by the queen to bring back Snow White's heart. While the heart is mentioned, it is never shown in the box. Snow White is also older and more mature. And she is discovered by the dwarfs after cleaning the house, not vandalizing it. Furthermore, in the Disney movie the evil queen tries only once to kill Snow White (with the poisoned apple) and fails. She then dies by falling down a cliff and being crushed by a boulder, after the dwarfs had chased her through the forest. In the original, the queen is forced to dance to death in red hot iron slippers.[23]

Variants and parallels to other tales

This tale type is widespread in Europe, in America, in Africa and "in some Turkic traditions," [24] the Middle East, in China, in India and in the Americas.[25] Jörg Bäcker draws a parallel to Turkic tales, as well as other tales with a separate origin but overlapping themes, such as those in Central Asia and Eastern Siberia, among the Mongolians and Tungusian peoples.[26] Due to Portuguese colonization, Sigrid Schmidt posits the presence of the tale in modern times in former Portuguese colonies, and contrasts it with other distinct African tales.[27]

Europe

A primary analysis by Celtic folklorist Alfred Nutt, in the 19th century, established the tale type, in Europe, was distributed "from the Balkan peninsula to Iceland, and from Russia to Catalonia", with the highest number of variants being found in Germany and Italy.[28]

This geographical distribution seemed to be confirmed by scholarly studies of the 20th century. A 1957 article by Italian philologist Gianfranco D'Aronco (it) studied the most diffused Tales of Magic in Italian territory, among which Biancaneve.[29] A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found thirty-seven variants of the tale across Italian sources.[30] A similar assessment was made by scholar Sigrid Schmidt, who claimed that the tale type was "particularly popular" in Southern Europe, "specially" in Italy, Greece and Iberian Peninsula.[27] In addition, Swedish scholar Waldemar Liungman suggested Italy as center of diffusion of the story, since he considered Italy as the source of tale ("Ursprung"), and it holds the highest number of variants not derived from the Grimm's tale.[31][32]

Another study, by researcher Theo Meder, points to a wide distribution in Western Europe, specially in Ireland, Iceland and Scandinavia.[25]

Germany

The Brothers Grimm's "Snow White" was predated by several other German versions of the tale, with the earliest being Johann Karl August Musäus's "Richilde" (1782), a satirical novella told from the wicked stepmother's point of view. Albert Ludwig Grimm (no relation to the Brothers Grimm) published a play version, Schneewittchen, in 1809.[33] The Grimms collected at least eight other distinct variants of the tale, which they considered one of the most famous German folktales.[34]

Italy

Giambattista Basile wrote and told his fairy tales well before Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, who knew and translated his fairy tales, so they also took inspiration from them. The masterpiece "Lo cunto de li cunti" published posthumously in the years 1634-1636 contains fairy tales inspired by real Italian characters, such as the case of "Lo cuorvo" o "Il corvo" ("The Raven").[17] This fairy tale tells of a King, a noble title used to facilitate understanding for children and to make them understand that he is someone who commands, who one day sees a dead crow in the snow, and the contrast of red blood on white strikes him so much that he does not want nothing more than a white-skinned, red-cheeked bride. This is one of the first inspirations for that character who in the course of the alterations of fairy tales and stories will become called Snow-White in the future. This idea was taken up by the Brothers Grimm, who knew and translated Basile into German. The character of Snow-White seems to be inspired by the marchioness Giovanna Zazzera (sometimes spelled Zazzera), of a family of Venetian origin (the family of Doge Marino Zorzi). The Marquise Giovanna Gianna Zazzera would have married Annibale of the Corvi family of Sulmona. The surname Corvi means "Ravens" maybe took because in ancient times a raven helped an ancestor in a battle, leaning on his helmet and attacking an enemy Gaul.[35] Thus in the character of Snow-White one finds raven-black hair, snow-white skin with red cheeks. Everything started from this fairy tale and since Basile also worked among the militias of Venice, during that period the story was told among the Venetians and from there it passed to Germany. It should be remembered that the Marchesa Giovanna Zazzera and the Baron Annibale Corvi lived in Abruzzo, where a version was then born that altered over time and always referred to Venice (because Giovanna Zazzera descended from Pietro Zorzi, brother of Doge Marino Zorzi).[36][37] Not surprisingly, according to another thesis, supported by the Treviso professor Giuliano Palmieri, the fairy tale of Snow White could be originally from the Dolomites of the Province of Belluno, and come from the Cordevole valleys. Where he probably arrived in this territory owned by Venice, when Basile worked in the Venetian militias.[38][39]

Among many things, the city of Sulmona where Giovanna Zazzera and Annibale Corvi lived, was the birthplace of the writer Ovidio Naso. Scholar Graham Anderson compares the tale to the Roman legend of Chione, or "Snow", recorded in Ovid's Metamorphoses. So once again the origins are fixed in Italy, again in the birthplace of Publius Ovidius Nasone, which would then later inspire Giambattista Basile together with the marriage of the Marquise Giovanna Zazzera with the Corvi family, to give life to the character.[40][41]

In most Italian versions the heroine is not the daughter of a king but an innkeeper, the antagonist is not her stepmother but her biological mother, and instead of dwarfs she takes refuge with robbers, as we can see in La Bella Venezia an Abruzzian version collected by Antonio De Nino, in which the mother asks her customers if they have seen a woman more beautiful than she. If they say they did not, she only charges them half the price, if they say they did she charges them twice the price. When the customers tell her that her daughter is prettier than her, she gets jealous.[42] In Maria, her Evil Stepmother and the Seven Robbers (Maria, die böse Stiefmutter und die sieben Räuber), a Sicilian version collected by Laura Gonzenbach the heroine also lives with robbers, but the antagonist is her stepmother and she's not an innkeeper.[43][44]

Sometimes the heroine's protectors are female instead of male, as in The Cruel Stepmother (La crudel matrigna), a variant collected by Angelo de Gubernatis in which, like in the Grimm's version, Snow White's counterpart, called here Caterina, is the daughter of a king, and the antagonist is her stepmother, who orders her servants to kill her stepdaughter after she hears people commenting how much prettier Caterina is than she. One day the two women are going to mass together. Instead of a male protector, Caterina takes refuge in a house by the seashore where an old woman lives. Later a witch discovers that Caterina's still alive and where she lives, so she goes to tell the queen, who sends her back to the cottage to kill her with poisoned flowers instead of an apple.[45] A similar version from Siena was collected by Sicilian folklorist Giuseppe Pitrè, in which the heroine, called Ermellina, runs away from home riding an eagle who takes her away to a palace inhabited by fairies. Ermellina's stepmother sends a witch disguised as her stepdaughter's servants to the fairies' palace to try to kill her twice, first with poisoned sweetmeats and the second time with an enchanted dress.[46] Pitré also collected a variant from Palermo titled Child Margarita (La 'Nfanti Margarita) where the heroine stays in a haunted castle.[47][48]

There's also a couple of conversions that combines the ATU tale type 709 with the second part of the type 410 Sleeping Beauty, in which, when the heroine is awakened, the prince's mother tries to kill her and the children she has had with the prince. Gonzenbach collected two variants from Sicily, the first one called Maruzzedda and the second Beautiful Anna; and Vittorio Imbriani collected a version titled La Bella Ostessina.[49][50]

In some versions, the antagonists are not the heroine's mother or stepmother, but her two elder sisters, as in a version from Trentino collected by Christian Schneller,[51] or a version from Bologna collected by Carolina Coronedi-Berti. In this last version, the role of both the mirror and the dwarfs is played by the Moon, which tells the elder sisters that the youngest, called Ziricochel, is the prettiest, and later hides her in his palace. When the sisters discover Ziricochel is still alive, they send an astrologer to kill her. After several attempts, she finally manages to turn her into a statue with an enchanted shirt. Ziricochel is revived after the prince's sisters take the shirt off.[52]

Italo Calvino included the version from Bologna collected by Coronedi Berti, retitling it Giricoccola, and the Abruzzian version collected by De Nino in Italian Folktales.

France

Paul Sébillot collected two variants from Brittany in northwestern France. In the first one, titled The Enchanted Stockings (Les Bas enchantés), starts similarly to Gubernatis' version, with the heroine being the daughter of a queen, and her mother wanting to kill her after soldier marching in front of her balcony says the princess is prettier than the queen. The role of the poisoned apple is fulfilled by the titular stockings, and the heroine is revived after the prince's little sister takes them off when she's playing.[53][54] In the second, titled La petite Toute-Belle, a servant accuses the heroine of stealing the things she stole and then throws her in a well. The heroine survives the fall and ends up living with three dragons that live at the bottom of the well. When the heroine's mother discovers her daughter is still alive, she twice sends a fairy to attempt to kill her, first with sugar almonds, which the dragons warn her are poisoned before she eats them, and then with a red dress.[55] In another version from Brittany, this one collected by François Cadic, the heroine is called Rose-Neige (Eng: Snow-Rose) because her mother pricked her finger with a rose in a snowy day and wished to have a child as beautiful as the rose. The role of the dwarfs is played by Korrigans, dwarf-like creatures from the Breton folklore.[56] Louis Morin collected a version from Troyes in northeastern France, where like in the Grimm's version the mother questions a magic mirror.[57] A version from Corsica titled Anghjulina was collected by Geneviève Massignon, where the roles of both the huntsman and the dwarfs are instead a group of bandits whom Anghjulina's mother asks to kill her daughter, but they instead take her away to live with them in the woods.[58]

Belgium and the Netherlands

A Flemish version from Antwerp collected by Victor de Meyere is quite similar to the version collected by the brothers Grimm. The heroine is called Sneeuwwitje (Snow White in Dutch), she is the queen's stepdaughter, and the stepmother questions a mirror. Instead of dwarfs, the princess is taken in by seven kabouters. Instead of going to kill Snow White herself, the queen twice sends the witch who had sold her the magic mirror to kill Sneeuwwitje, first with a comb and the second time with an apple. But the most significant difference is that the role of the prince in this version is instead Snow White's father, the king.[59]

Another Flemish variant, this one from Hamme, differs more from Grimm's story. The one who wants to kill the heroine, called here Mauricia, is her own biological mother. She is convinced by a demon with a spider head that if her daughter dies, she will become beautiful. The mother sends two servants to kill Mauricia, bringing as proof a lock of her hair, a bottle with her blood, a piece of her tongue and a piece of her clothes. The servants spare Mauricia's life, as well as her pet sheep. To deceive Mauricia's mother, they buy a goat and bring a bottle with the animal's blood as well as a piece of his tongue. Meanwhile, Mauricia is taken in by seventeen robbers who live in a cave deep in the forest, instead of seven dwarfs. When Mauricia's mother discovers that her daughter is still alive, she goes to the robbers' cave disguised. She turns her daughter into a bird, and she takes her place. The plan fails and Mauricia recovers her human form, so the mother tries to kill her by using a magic ring which the demon gave her. Mauricia is awoken when a prince takes the ring off her finger. When he asks her if he would marry her, she rejects him and returns with the seventeen robbers.[60][61]

Iberian Peninsula

One of the first versions from Spain, titled The Beautiful Stepdaughter (La hermosa hijastra), was collected by Manuel Milà i Fontanals, in which a demon tells the stepmother that her stepdaughter is prettier than she is when she's looking at herself in the mirror. The stepmother orders her servants to take her stepdaughter to the forest and kill her, bringing a bottle with her blood as proof. But the servants spare her life and instead kill a dog. Eight days later the demon warns her that the blood in the bottle is not her stepdaughter's, and the stepmother sends her servants again, ordering them to bring one of her toes as proof. The stepdaughter later discovers four men living in the forest, inside a rock that can open and close with the right words. Every day after she sees the men leave she enters the cave and cleans it up. Believing it must be an intruder, the men take turns to stay at the cavern, but the first one falls asleep during his watch. The second one manages to catch the girl, and they agree to let the girl live with them. Later, the same demon that told her stepmother that her stepdaughter was prettier gives the girl an enchanted ring, that has the same role that the apple in the Grimm's version.[62] The version in Catalan included by Francisco Maspons y Labrós in the second volume of Lo Rondallayre follows that plot fairly closely, with some minor differences.[63]

In an Aragonese version titled The Good Daughter (La buena hija) collected by Romualdo Nogués y Milagro, there's no mirror. Instead, the story starts with the mother already hating her daughter because she's prettier, and ordering a servant to kill her, bringing as proof her heart, tongue, and her little finger. The servant spares her and brings the mother the heart and tongue from a dog he ran over and says he lost the finger. The daughter is taken in by robbers living in a cavern, but despite all, she still misses her mother. One day an old woman appears and gives her a ring, saying that if she puts it on she'll see her mother. The daughter actually falls unconscious when she does put it on because the old woman is actually a witch who wants to kidnap her, but she can't because of the scapular the girl is wearing, so she locks her in a crystal casket, where the girl is later found by the prince.[64]

In a version from Mallorca collected by Antoni Maria Alcover i Sureda titled Na Magraneta, a queen wishes to have a daughter after eating a pomegranate and calls her Magraneta. As in the Grimm's version the queen asks her mirror who's the most beautiful. The dwarf's role is fulfilled by thirteen men who are described as big as giants, who live in a castle in the middle of the forest called "Castell de la Colometa", whose doors can open and close by command. When the queen discovers thanks to her mirror that her daughter is still alive she sends an evil fairy disguised as an old woman. The role of the poisoned apple is fulfilled by an iron ring.[65]

Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr. collected two Spanish versions. The first one, titled Blanca Flor, is from Villaluenga de la Sagra, in Toledo. In this one the villain is the heroine's own biological mother, and like in Na Magraneta she questions a mirror if there's a woman more beautiful than she is. Instead of ordering a huntsman or servant to kill her daughter, after the mirror tells the woman her daughter has surpassed her, she tries to get rid of her daughter herself, inviting her to go for a walk in the countryside, and when they reach a rock she recites some spells from her book, making the rock swallow her daughter. Fortunately thanks to her prayers to the Virgin the daughter survives and gets out the rock, and she is later taken in by twelve robbers living in a castle. When the mother discovers her daughter is still alive, she sends a witch to kill her, who gives the daughter an enchanted silk shirt. The moment she puts it on, she falls in a deathlike state. She's later revived when a sexton takes the shirt off.[66] The second one, titled The Envious Mother (La madre envidiosa), comes from Jaraíz de la Vera, Cáceres. Here the villain is also the heroine's biological mother, and she's an innkeeper who asks a witch whether there's a woman prettier than she is. Instead of a shirt, here the role of the apple is fulfilled by enchanted shoes.[67] Aurelio de Llano Roza de Ampudia collected an Asturian version from Teverga titled The Envious Stepmother (La madrastra envidiosa), in which the stepmother locks her stepdaughter in a room with the hope that no one will see her and think she's more beautiful. But the attempt fails when a guest tells the mother the girl locked in a room is prettier than she is. The story ends with the men who found the heroine discussing who should marry the girl once she's revived, and she replies by telling them that she chooses to marry the servant who revived her.[68] Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Jr. collected four versions. The first one is titled Blancanieves, is from Medina del Campo, Valladolid, and follows the plot of the Grimm's version fairly closely with barely any significant differences.[69] The same happens with the second one, titled Blancaflor, that comes from Tordesillas, another location from Valladolid.[70] The last two are the ones that present more significant differences, although like in Grimm's the stepmother questions a magic mirror. The Bad Stepmother (La mala madrastra) comes from Sepúlveda, Segovia, and also has instead of seven dwarfs the robbers that live in a cave deep in the forest, that can open and close at command. Here the words to make it happen are "Open, parsley!" and "Close, peppermint!"[71] The last one, Blancaflor, is from Siete Iglesias de Trabancos, also in Valladolid, ends with the heroine buried after biting a poisoned pear, and the mirror proclaiming that, now that her stepdaughter is finally dead, the stepmother is the most beautiful again.[72]

One of the first Portuguese versions was collected by Francisco Adolfo Coelho. It was titled The Enchanted Shoes (Os sapatinhos encantados), where the heroine is the daughter of an innkeeper, who asks muleteers if they have seen a woman prettier than she is. One day, one answers that her daughter is prettier. The daughter takes refugee with a group of robbers who live in the forest, and the role of the apple is fulfilled by the titular enchanted shoes.[73] Zófimo Consiglieri Pedroso collected another version, titled The Vain Queen, in which the titular queen questions her maids of honor and servants who's the most beautiful. One day, when she asks the same question to her chamberlain, he replies the queen's daughter is more beautiful than she is. The queen orders her servants to behead her daughter bring back his tongue as proof, but they instead spare her and bring the queen a dog's tongue. The princess is taken in by a man, who gives her two options, to live with him as either his wife or his daughter, and the princess chooses the second. The rest of the tale is quite different from most versions, with the titular queen completely disappeared from the story, and the story focusing instead of a prince that falls in love with the princess.[73]

British Isles

In the Scottish version Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree, queen Silver-Tree asks a trout in a well, instead of a magic mirror, who's the most beautiful. When the trout tells her that Gold-Tree, her daughter, is more beautiful, Silver-Tree pretends to fall ill, declaring that her only cure is to eat her own daughter's heart and liver. To save his daughter's life, the king marries her off to a prince, and serves his wife a goat's heart and liver. After Silver-Tree discovers that she has been deceived thanks to the trout, she visits her daughter and sticks her finger on a poisoned thorn. The prince later remarries, and his second wife removes the poisoned thorn from Gold-Tree, reviving her. The second wife then tricks the queen into drinking the poison that was meant for Gold-Tree.[74] In another Scottish version, Lasair Gheug, the King of Ireland's Daughter, the heroine's stepmother frames the princess for the murder of the queen's firstborn and manages to make her swear she'll never tell the truth to anybody. Lasair Gheug, a name that in Gaelic means Flame of Branches, take refugee with thirteen cats, who turn out to be an enchanted prince and his squires. After marrying the prince and having three sons with him the queen discovers her stepdaughter is still alive, also thanks to a talking trout, and sends three giants of ice to put her in a death-like state. As in Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree the prince takes a second wife afterwards, and the second wife is the one who revives the heroine.[75] Thomas William Thompson collected an English version from Blackburn simply titled Snow White which follows Grimm's plot much more closely, although with some significant differences, such as Snow White being taken in by three robbers instead of seven dwarfs.[76]

Scandinavia

One of the first Danish versions collected was Snehvide (Snow White), by Mathias Winther. In this variant, the stepmother is the princess' nurse, who persuades Snow White to ask her father to marry her. Because the king says he won't remarry until grass grows in the grave of the princess' mother, the nurse plants magic seeds in the grave so grass will grow quicker. Then, after the king marries the nurse, Snow White gets betrothed to a prince, who choses her over the nurse's three biological daughters, but after that the king and the prince had to leave to fight in a war. The queen seizes her opportunity to chase Snow White away, and she ends up living with the dwarfs in a mountain. When the queen finds out Snow White is still alive thanks to a magic mirror, she sends her daughters three times, each time one of them, with poisoned gifts to give them to her. With the third gift, a poisoned apple, Snow White falls into a deep sleep, and the dwarfs leave her in the forest, fearing that the king would accuse them of killing her once he comes back. When the king and the prince finally come back from the war and find Snow White's body, the king dies of sorrow, but the prince manages to wake her up. After that we see an ending quite similar to the ones in The Goose Girl and The Three Oranges of Love the prince and Snow White get married, and the prince invites the stepmother and asks her what punishment deserve someone who has hurt someone as innocent as Snow White. The queen suggests for the culprit to be put inside a barrel full of needles, and the prince tells the stepmother she has pronounced her own sentence.[77] Evald Tang Kristensen collected a version titled The Pretty Girl and the Crystal Bowls (Den Kjønne Pige og de Klare Skåle), which, like some Italian variants, combines the tale type 709 with the type 410. In this version, the stepmother questions a pair of crystal bowls instead of a magic mirror, and when they tell her that her stepdaughter is prettier, she sends her to a witch's hut where she's tricked to eat a porridge that makes her pregnant. Ashamed that her daughter has become pregnant out of wedlock she kicks her out, but the girl is taken in by a shepherd. Later a crow lets a ring fall on the huts' floor, and, when the heroine puts it on, she falls in a deathlike state. Believing she's dead the shepherd kills himself and the heroine is later revived when she gives birth to twins, each one of them with a star on the forehead, and one of them sucks the ring off her finger. She's later found by a prince, whose mother tries to kill the girl and her children.[78][79]

A Swedish version titled The Daughter of the Sun and the Twelve Bewitched Princes (Solens dotter och de tolv förtrollade prinsarna) starts pretty similarly to the Grimm's version, with a queen wishing to have a child as white as snow and as red as blood, but that child turned out to be not the heroine but the villain, her own biological mother. Instead of a mirror, the queen asks the Sun, who tells her that her daughter will surpass her in beauty. Because of it the queen orders that her daughter must be raised in the countryside, away from the Royal Court, but when It's time for the princess to come back the queen orders a servant to throw her in a well before she arrives. In the bottom, the princess meets twelve princes cursed to be chimeras, and she agrees to live with them. When the queen and the servant discover she's alive, they give her poisoned candy, which she eats. After being revived by a young king she marries him and has a son with him, but the queen goes to the castle pretending to be a midwife, turns her daughter into a golden bird by sticking a needle on her head, and then the queen takes her daughter's place. After disenchanting the twelve princes with her singing, the princess returns to the court, where she's finally restored to her human form, and her mother is punished after she believed she ate her own daughter while she was still under the spell.[80]

Greece and Mediterranean area

French folklorist Henri Carnoy collected a Greek version, titled Marietta and the Witch her Stepmother (Marietta et la Sorcière, sa Marâtre), in which the heroine is manipulated by her governess to kill her own mother, so the governess could marry her father. Soon after she marries Marietta's father, the new stepmother orders her husband to get rid of his daughter. Marietta ends up living in a castle with forty giants. Meanwhile, Marietta's stepmother, believing her stepdaughter is dead, asks the Sun who's the most beautiful. When the Sun answers Marietta is more beautiful, she realises her stepdaughter is still alive, and, disguised as a peddler, goes to the giants' castle to kill her. She goes twice, the first trying to kill her with an enchanted ring, and the second with poisoned grapes. After Marietta is awoken and marries the prince, the stepmother goes to the prince's castle pretending to be a midwife, sticks a fork on Marietta's head to turn her into a pigeon, and then takes her place. After several transformations, Marietta recovers her human form and her stepmother is punished.[81] Georgios A. Megas collected another Greek version, titled Myrsina, in which the antagonists are the heroine's two elder sisters, and the role of the seven dwarfs is fulfilled by the Twelve Months.[82]

Austrian diplomat Johann Georg von Hahn collected a version from Albania, that also starts with the heroine, called Marigo, killing her mother so her governess can marry her father. But after the marriage, Marigo's stepmother asks the king to get rid of the princess, but instead of killing her the king just abandons her daughter in the woods. Marigo finds a castle inhabited by forty dragons instead of giants, that take her in as their surrogate sister. After discovering her stepdaughter is still alive thanks also to the Sun, the queen twice sends her husband to the dragons' castle to kill Marigo, first with enchanted hair-pins and the second time with an enchanted ring.[83] In another Albanian version, titled Fatimé and collected by French folklorist Auguste Dozon, the antagonists are also the heroine's two elder sisters, as in Myrsina.[84]

Russia and Eastern Europe

According to Christine Shojaei Kawan, the earliest surviving folktale version of the Snow White story is a Russian tale published anonymously in 1795. The heroine is Olga, a merchant's daughter, and the role of the magic mirror is played by some beggars who comment on her beauty.[85] In the Russian tale, titled "Сказка о старичках-келейчиках", a merchant has a daughter named Olga, and marries another woman. Years later, the girl's stepmother welcomes some beggars in need of alms, who tell her Olga is more beautiful than her. A servant takes Olga to the open field and, in tears, tells the girl the stepmother ordered her to be killed and her heart and little finger brought back as proof of the deed. Olga cuts off her little finger and gives to the servant, who kills a little dog and takes out its heart. Olga takes refuge in a cottage with hunters, and asks the beggars to trade gifts with her stepmother: Olga sends a pie, and her stepmother sends her a poisoned pearl-studded shirt. Olga puts on the shirt and faints, as if dead. The hunters find her apparently dead body and place it in a crystal tomb. A prince appears to them and asks to take the coffin with him to his palace. Later, the prince's mother takes off the pearl-studded shirt from Olga's body and she wakes up.[86]

Alexander Afanasyev collected a Russian version titled The Magic Mirror, in which the reason that the heroine has to leave her parents' house is different from the usual. Instead of being the daughter of a king, she is the daughter of a merchant, who's left with her uncle while her father and brothers travel. During their absence, the heroine's uncle attempts to assault her, but she frustrates his plans. To get his revenge he writes a letter to the heroine's father, accusing her of misconduct. Believing what's written in the letter, the merchant sends his son back home to kill his own sister, but the merchant's son does not trust his uncle's letter, and after discovering what's in the letter are lies, he warns her sister, who escapes and is taken in by two bogatyrs. The elements of the stepmother and the mirror are introduced much later, after the merchant returns home believing his daughter is dead and remarries the woman who owns the titular magic mirror, that tells her that her stepdaughter is still alive and is more beautiful than she is.[87] In another Russian version the heroine is the daughter of a Tsar, and her stepmother decides to kill her after asking three different mirrors and all of them told her her stepdaughters is more beautiful than she is. The dwarfs' role is fulfilled by twelve brothers cursed to be hawks, living at the top of a glass mountain.[88]

Arthur and Albert Schott collected a Romanian version titled The Magic Mirror (German: Der Zauberspiegel; Romanian: Oglinda fermecată), in which the villain is the heroine's biological mother. After the titular mirror tells her that her daughter is prettiest, she takes her to go for a walk in the woods and feeds her extremely salty bread, so her daughter will become so thirsty that she would agree to let her tear out her eyes in exchange for water. Once the daughter is blinded her mother leaves her in the forest, where she manages to restore her eyes and is taken in by twelve thieves. After discovering her daughter is still alive, the mother sends an old woman to the thieves' house three times. The first she gives the daughter a ring, the second earrings, and the third poisoned flowers. After the heroine marries the prince, she has a child, and the mother goes to the castle pretending to be a midwife to kill both her daughter and the newborn. After killing the infant, she's stopped before she can kill the heroine.[89]

The Pushkin fairytale The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights bears a striking similarity to the tale of Snow White. However, the Dead Princess befriends 7 knights instead of dwarfs, and it is the Sun and Moon who aid the Prince to the resting place of the Dead Princess, where he breaks with his sword the coffin of the Tsarevna, bringing her back to life.

Americas

In a Louisiana tale, Lé Roi Pan ("The King Peacock"), a mother has a child who becomes more beautiful than she, so she orders her daughter's nurse to kill her. The daughter resigns to her fate, but the nurse spares her and gives her three seeds. After failing to drown in a well and to be eaten by an ogre, the girl eats a seed and falls into a deep sleep. The ogre family (who took her in after seeing her beauty) put her in a crystal coffin to float down the river. Her coffin is found by the titular King Peacock, who takes the seed from her mouth and awakens her.[90] The King Peacock shares "motifs and tropes" with Snow White, according to Maria Tatar.[91]

Adaptations

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Theatrical - Live-action

- Snow White (1902), a lost silent film made in 1902. It was the first time the classic 1812 Brothers Grimm fairy tale was made into a film.

- Snow White (1916), a silent film by Famous Players–Lasky produced by Adolph Zukor and Daniel Frohman, directed by J. Searle Dawley, and starring Marguerite Clark, Creighton Hale, and Dorothy Cumming.

- I sette nani alla riscossa (The Seven Dwarfs to the Rescue) (1951), an Italian film based on the fairy tale.

- Lumikki ja 7 jätkää (The Snow White and the 7 Dudes) (1953), a Finnish musical comedy film directed by Ville Salminen, loosely based on the fairy tale.[92]

- Schneewittchen und die sieben Zwerge (1955), a German live-action adaptation of the fairy tale.

- Snow White and the Seven Fellows (1955), a Hong Kong film as Chow Sze-luk, Lo Yu-kei Dirs

- Snow White and the Three Stooges (1961), starring the Three Stooges with Carol Heiss as Snow White and Patricia Medina as the Evil Queen.

- Snow White (1962), an East German fairy tale film directed by Gottfried Kolditz.

- The New Adventures of Snow White (1969), a West German sex comedy film directed by Rolf Thiele and starring Marie Liljedahl, Eva Reuber-Staier, and Ingrid van Bergen. The film puts an erotic spin on three classic fairy tales Snow White, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty.

- Pamuk Prenses ve 7 Cüceler (1970), a Turkish live-action remake of the 1937 Disney film.

- Snow White (1987), starring Diana Rigg as the Evil Queen and Nicola Stapleton and Sarah Patterson both as Snow White.

- Schneewittchen und das Geheimnis der Zwerge (1992), a German adaptation of the fairy tale.

- Snow White: A Tale of Terror (1997), starring Sam Neill as Snow White's father, Sigourney Weaver as the Evil Queen, and Monica Keena as Snow White.

- 7 Dwarves – Men Alone in the Wood (7 Zwerge – Männer allein im Wald) (2004), a German comedy film

- The Brothers Grimm (2005), an adventure fantasy film directed by Terry Gilliam and starring Matt Damon, Heath Ledger, and Lena Headey

- 7 Dwarves: The Forest Is Not Enough (7 Zwerge – Der Wald ist nicht genug) (2006), sequel to the 2004 German film 7 Dwarves – Men Alone in the Wood

- Sydney White (2007), a modernization, starring Amanda Bynes

- Blancanieves (2012), a silent Spanish film based on the fairy tale.

- Mirror Mirror (2012), starring Julia Roberts as the Evil Queen Clementianna,[93] Lily Collins as Snow White, Armie Hammer as Prince Andrew Alcott, and Nathan Lane as Brighton, the Queen's majordomo.[94]

- The Huntsman series:

- Snow White and the Huntsman (2012), starring Kristen Stewart, Charlize Theron, Chris Hemsworth, and Sam Claflin.

- The Huntsman: Winter's War (2016), which features Snow White as a minor character.

- White as Snow (2019), starring Lou de Laâge, Isabella Huper

- Snow White (2024), an upcoming remake of Disney's 1937 animated version, starring Rachel Zegler as Snow White, Gal Gadot as the Evil Queen, and Andrew Burnap as a new character named Jonathan.

- Snow White and the Evil Queen (2024), an upcoming film by Bentkey starring Brett Cooper as Snow White.

Theatrical - Animation

- Snow-White (1933), also known as Betty Boop in Snow-White, a film in the Betty Boop series from Max Fleischer's Fleischer Studios.

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), an animated film based on the fairy tale, featuring Adriana Caselotti as the voice of Snow White. It is widely considered the best-known adaptation of the story, thanks in part to it becoming one of the first animated feature films and Disney's first animated motion picture.

- Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs (1943) is a Merrie Melodies animated cartoon directed by Bob Clampett. The short was released on January 16, 1943. It is a parody of the fairy tale featuring African-American stereotypes.

- Happily Ever After (1989) is a 1989 American animated musical fantasy film written by Robby London and Martha Moran, directed by John Howley, produced by Filmation.

- Snow White: The Sequel (2007) is a Belgian/French/British adult animated comedy film directed by Picha. It is based on the fairy tale of Snow White and intended as a sequel to Disney's classic animated adaptation. However, like all of Picha's cartoons, the film is actually a sex comedy featuring a lot of bawdy jokes and sex scenes.

- The Seventh Dwarf (2014) (German: Der 7bte Zwerg), is a German 3D computer-animated film, created in 2014. The film is based upon the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty and characters from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Direct-to-video - Animation

- Amada Anime Series: Super Mario Bros. (1989), a three-part OVA series featuring Mario characters in different fairy tales.

- Snow White and the Magic Mirror (1994), produced by Fred Wolf Films Dublin.

- Snow White (1995), a Japanese-American direct-to-video film by Jetlag Productions.

- Happily N'Ever After 2: Snow White—Another Bite @ the Apple (2009), an American-German computer-animated direct-to-video film and sequel to Happily N'Ever After

- Charming (2018), an animated film featuring Snow White as one of the princesses, featuring the voice of Avril Lavigne.

- Red Shoes and the Seven Dwarfs (2019), a Korean-American animated film based on the fairy tale, featuring the voice of Chloë Grace Moretz.[95]

Animation - Television

- Festival of Family Classics (1972–73), episode Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, produced by Rankin/Bass and animated by Mushi Production.

- Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi (1976–79), anime anthology series animated by Dax International has a 10-minute adaptation.

- A Snow White Christmas is a Christmas animated television special produced by Filmation and telecast December 19, 1980, on CBS.

- A 1984 episode of Alvin & the Chipmunks called Snow Wrong is based on the fairy tale, with Brittany of The Chipettes as Snow White.

- The Saturday-morning cartoon series Muppet Babies parodied the tale in "Snow White and the Seven Muppets" (1985).

- My Favorite Fairy Tales (Sekai Dōwa Anime Zenshū) (1986), an anime television anthology, has a 30-minute adaptation.

- Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics (1987–89) an anime television series based on Grimm's stories, as a four half-hour episodes adaptation.

- Season 7 of Garfield and Friends had a two-part story parodying the fairy tale called "Snow Wade and the 77 Dwarfs".

- World Fairy Tale Series (Anime sekai no dōwa) (1995), anime television anthology produced by Toei Animation, has half-hour adaptation.

- Wolves, Witches and Giants (1995–99), special Snow White (1997).

- The Triplets (Les tres bessones/Las tres mellizas) (1997-2003), catalan animated series, season 1 episode 2.

- Simsala Grimm (1999-2010), season 2 episode 8.

- The Rugrats also act out the fairy tale with Angelica Pickles as The Evil Queen. Susie Carmichael as Snow White and Tommy Pickles, Dil Pickles, Kimi Finster, Chuckie Finster, Phil and Lil DeVille and Spike the Dog as The Seven Dwarfs.

- Animated webseries Ever After High (2013-2017) based on the same name doll line, features as main characters Raven Queen, daughter of the Evil Queen, and Apple White, daughter of Snow White. The two protagonists' mothers also appear in the Dragon Games special.

- RWBY (2013) is a web series which features characters called "Weiss Schnee" and "Klein Sieben", German for "White Snow" and "Small Seven" (grammatically incorrect, though, since it would be "Weisser Schnee" and "Kleine Sieben").

- In The Simpsons episode "Four Great Women and a Manicure" (2009), Lisa tells her own variation of the tale, with herself as Snow White.

- Revolting Rhymes (2016), TV film based on the 1982 book of the same name written by Roald Dahl featuring Snow White as one of the main characters.

- A 2016 video on the Pudding TV Fairy Tales YouTube channel tells a comical version of the story.

Live-action - Television

- The Brady Bunch (1973), in the episode "Snow White and the Seven Bradys", the Bradys put on a production of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" in their backyard, with each of the Brady's playing one of the characters.

- El Chapulín Colorado (1978), in the three part episode "Blancanieves y los siete Churi Churín Fun Flais" being crossover with El Chavo del Ocho where Chapulin visits Profesor Jirafales' class to narrate the story of Snow White for the children. Snow White is played by Florinda Meza while the Evil Queen is played by María Antonieta de las Nieves.

- Faerie Tale Theatre (1984) has an episode based on the fairy tale starring Vanessa Redgrave as the Evil Queen, Elizabeth McGovern as Snow White, and Vincent Price as the Magic Mirror.

- A Smoky Mountain Christmas (1986) is a retelling of Snow White, except it is set in the Smoky Mountains and there are orphans instead of dwarves.

- Saved by the Bell (1992), in the episode "Snow White and the Seven Dorks", the school puts on a hip hop version of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs".

- The 10th Kingdom (2000) is a TV miniseries featuring Snow White as a major character.

- Snow White: The Fairest of Them All (2001), starring Kristin Kreuk as Snow White and Miranda Richardson as Queen Elspeth.

- Schneewittchen (2009), a German made-for-television film starring Laura Berlin as Snow White.

- Blanche Neige (2009) - France TV movie

- Once Upon a Time (2011) is a TV series featuring Snow White, Prince Charming, their daughter Emma Swan, and the Evil Queen as the main characters.

Live-action - Direct-to-video

- Neberte nám princeznú (1981) (English: Let the Princess Stay with Us) is a modern version of the Snowhite and the Seven Dwarfs fairytale, starring Marika Gombitová. The musical was directed by Martin Hoffmeister, and released in 1981.

- Grimm's Snow White (2012), starring Eliza Bennett as Snow White and Jane March as the Evil Queen Gwendolyn.

- Snow White: A Deadly Summer (2012) is an American horror film directed by David DeCoteau and starring Shanley Caswell, Maureen McCormick, and Eric Roberts. The film was released straight to DVD and digital download on March 20, 2012

Music and audio

- Sonne (2001) is a music video for the song by Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein, where the band are dwarfs mining gold for Snow White.

- Charmed (2008), an album by Sarah Pinsker, features a song called "Twice the Prince" in which Snow White realizes that she prefers a dwarf to Prince Charming.

- The Boys (2011), Girls' Generation's third studio album, features a concept photo by Taeyeon inspired by Snow White.

- Hitoshizuku and Yamasankakkei are two Japanese Vocaloid producers that created a song called Genealogy of Red, White and Black (2015) based upon the tale of Snow White with some differences, the song features the Vocaloids Kagamine Rin/Len and Lily.

- John Finnemore's Souvenir Programme S5E1 (2016) features a comedy sketch parodying the magic mirror scene.[96][97][98]

- The music video of Va Va Voom (2012) features Nicki Minaj in a spoof of the fairy tale.

In literature

- German author Ludwig Aurbacher used the story of Snow White in his literary tale Die zwei Brüder ("The Two Brothers") (1834).[99]

- Snow White (1967), a postmodern novel by Donald Barthelme which describes the lives of Snow White and the dwarfs.

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1971), a poem by Anne Sexton in her collection Transformations, in which she re-envisions sixteen of the Grimm's Fairy Tales.[100]

- Snow White in New York (1986), a picture book by Fiona French set in 1920s New York.

- "Snow White" (1994), a short story written by James Finn Garner, from Politically Correct Bedtime Stories: Modern Tales For Our Life & Times.

- "Snow, Glass, Apples", a 1994 short story written by Neil Gaiman, which all but explicitly rewrites the tale to make Snow White a vampire-like entity that is opposed by the Queen, while the prince is strongly implied to have necrophiliac tastes.

- Black as Night, 2004 novel by Regina Doman set in contempoary New York City.

- Six-Gun Snow White (2013), a novel by Catherynne M. Valente retelling the Snow White story in an Old West setting.

- Three modern-day "adaptations of... popular international fairy tales" were recorded in Puerto Rico. Two named "Blanca Nieves" ("Snow White") and the third "Blanca Flor" ("White Flower").[101]

- Tímakistan (2013), a novel by Andri Snær Magnason, an adaptation of Snow White.

- Boy, Snow, Bird (2014), a novel by Helen Oyeyemi which adapts the Snow White story as a fable about race and cultural ideas of beauty.[102]

- Winter (2015), a novel by Marissa Meyer loosely based on the story of Snow White.

- Girls Made of Snow and Glass (2017), a novel by Melissa Bashardoust which is a subversive, feminist take on the original fairy tale.[103]

- Sadie: An Amish Retelling of Snow White (2018) by Sarah Price

- Shattered Snow (2019), a time travel novel by Rachel Huffmire, ties together the life of Margaretha von Waldeck and the Grimm Brothers' rendition of Snow White.

- The Princess and the Evil Queen (2019), a novel by Lola Andrews, retells the story as a sensual love tale between Snow White and the Evil Queen.

In theatre

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1912), a play by Jessie Braham

- Snövit (1950), play by Astrid Lindgren

- The story of Snow White is a popular theme for British pantomime.

In comics

- The Haunt of Fear (1953) was a horror comic which featured a gruesome re-imaging of Snow White.

- Prétear (Prétear - The New Legend of Snow-White) is a manga (2000) and anime (2001) loosely inspired by the story of Snow White, featuring a sixteen-year-old orphan who meets seven magical knights sworn to protect her.

- Stone Ocean (2002), the sixth part of the long-running manga series, JoJo's Bizarre Adventure by Hirohiko Araki features Snow White as one of the various fictional characters brought to life by the stand, Bohemian Rhapsody. She also appeared in its anime adaptation.

- Fables (2002), a comic created by Bill Willingham, features Snow White as a major character in the series.

- MÄR (Märchen Awakens Romance) is a Japanese manga (2003) and anime (2005) series where an ordinary student (in the real world) is transported to another reality populated by characters that vaguely resemble characters from fairy tales, like Snow White, Jack (from Jack and the Beanstalk) and Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz.

- Snow White with the Red Hair is a manga (2006) and anime (2015) which open with a loose adaptation of the fairy tale, with a wicked prince pursuing a girl with strikingly red hair.

- Junji Ito's Snow White (2014) is a manga by Junji Ito retelling the story with Snow White repeatedly resurrecting from murders at the hands of the Queen.

- Monica and Friends has many stories that parody Snow White. Notably one of the stories "Branca de Fome e os Sete Anões" was adapted into an animated episode.

Video games

- Dark Parables (2010–present), a series of computer video games featuring fairy tales. Snow White appears as a recurring character in a few installments.

Other

- The Pucca Spring/Summer 2011 fashion show was inspired by Snow White and her wicked stepmother, the Queen. The opening model, Stella Maxwell, was dressed as a Lolita-esque modern day Snow White in a hoodie, miniskirt and high heels.[104] Due to her towering shoes, she fell on the catwalk and dropped the red apple she was carrying.[105]

- Joanne Eccles, an equestrian acrobat, won the title of Aerobatic World Champion (International Jumping of Bordeaux) in 2012. She interpreted Snow White during the first part of the event.

- In the doll franchise Ever After High, Snow White has a daughter named Apple White, and the Queen has a daughter named Raven Queen.

- The Wolf Among Us (2013), the Telltale Games video game based on the comic book series Fables.

- In the Efteling amusement park, Snow White and the dwarfs live in the Fairytale Forest adjoining the castle of her mother-in-law.

Religious interpretation

Erin Heys'[106] "Religious Symbols" article at the website Religion & Snow White analyzes the use of numerous symbols in the story, their implications, and their Christian interpretations, such as the colours red, white, and black; the apple; the number seven; and resurrection.[107]

See also

- The Glass Coffin

- Princess Aubergine

- Sleeping Beauty (a princess cursed into a death-like sleep)

- Snow-White-Fire-Red, an Italian fairy tale

- Snežana, a Slavic female name meaning "snow woman" with a similar connotation to "Snow White"

- Snegurochka, a Russian folk tale often translated as "Snow White"

- Syair Bidasari, a Malay poem with some plot similarities to "Snow White"

- Udea and her Seven Brothers

- The Tale of the Dead Princess and the Seven Knights (Alexander Pushkin's fairy tale in verse form)

References

- Jacob Grimm & Wilhelm Grimm: Kinder- und Hausmärchen; Band 1, 7. Ausgabe (children's and households fairy tales, volume 1, 7th edition). Dietrich, Göttingen 1857, page 264–273.

- Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (2014-10-19). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First ... Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-5189-8. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- Bartels, Karlheinz (2012). Schneewittchen – Zur Fabulologie des Spessarts. Geschichts- und Museumsverein Lohr a. Main, Lohr a. Main. pp. 56–59. ISBN 978-3-934128-40-8.

- Heidi Anne Heiner. "Tales Similar to Snow White and the 7 Dwarfs". Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- English translation of the original

- Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Wilhelm (2014). Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16059-7. OCLC 879662315., I pp. 184-85.

- Jacobs, Joseph. Europa's Fairy Book. London: G. Putnam and Sons. 1916. pp. 260–261.

- Goldberg, Christine (1993). "Review of Steven Swann Jones: The New Comparative Method: Structural and Symbolic Analysis of the Allomotifs of 'Snow White'". The Journal of American Folklore. 106 (419): 104. doi:10.2307/541351. JSTOR 541351.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book XI, 289

- Anderson, Graham (2000). Fairytale in the ancient world. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23702-4. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Sander, Eckhard (1994). Schneewittchen: Marchen oder Wahrheit?: ein lokaler Bezug zum Kellerwald.

- Bartels, Karlheinz (2012). Schneewittchen – Zur Fabulologie des Spessarts. Geschichts- und Museumsverein Lohr a. Main, Lohr a. Main; second edition. ISBN 978-3-934128-40-8.

- Vorwerk, Wolfgang (2015). Das 'Lohrer Schneewittchen' – Zur Fabulologie eines Märchens. Ein Beitrag zu: Christian Grandl/ Kevin J.McKenna, (eds.) Bis dat, qui cito dat. Gegengabe in Paremiology, Folklore, Language, and Literature. Honoring Wolfgang Mieder on His Seventieth Birthday. Peter Lang Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien. pp. 491–503. ISBN 978-3-631-64872-8.

- Stewart, Sara (March 25, 2012). "Snow White becomes a girl-power icon". The New York Post.

- Kawan, Christine Shojaei (June 2005). "Innovation, persistence and self-correction: the case of Snow White" (PDF). Estudos de Literatura Oral. 11–12: 238.

- The decisive statements in the Snow White fairy tale are at the very beginning in the 6th and 7th lines. "And as soon as the child was born, the queen died." "Over a year the king took another wife." Does that also apply to the "Lohrer Schneewittchen Maria Sophia"?

- The Pentamerone of Giambattista Basile - Volume/book 2 - by Giambattista Basile, Benedetto Croce · year 1979

- Ernst Böklen, Schneewittchenstudien: Erster Teil, Fünfundsiebzig Varianten im ergen Sinn (Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1910).

- Jones, Steven Swann (1983). "The Structure of Snow White". Fabula. 24 (1–2): 56–71. doi:10.1515/fabl.1983.24.1-2.56. S2CID 161709267. reprinted and slightly expanded in Fairy Tales and Society: Illusion, Allusion, and Paradigm, ed. by Ruth B. Bottigheimer (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1986), pp. 165–84. The material is also repeated in a different context in his The New Comparative Method: Structural and Symbolic Analysis of the Allomotifs of Snow White (Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1990).

- Kay Stone, "Three Transformations of Snow White", in The Brothers Grimm and Folktale, ed. by James M. McGlathery (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), pp. 52–65 (pp. 57-58); ISBN 0-252-01549-5

- Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 36; ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- Orbach, Israel (1960). "The Emotional Impact of Frightening Stories on Children". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1 (3): 379–389. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb00999.x. PMID 8463375.

- Grimm's Complete Fairy Tales, p. 194; ISBN 978-1-60710-313-4

- Haney, Jack V. (2015). The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas'ev, Volume II. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 536–556. ISBN 978-1-4968-0275-0.

- Meder, Theo. "Sneeuwwitje". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. p. 336.

- Bäcker, Jörg (1 December 2008). "Zhaos Mergen und Zhanglîhuâ Katô. Weibliche Initiation, Schamanismus und Bärenkult in einer daghuro-mongolischen Schneewittchen-Vorform" [Zhaos Mergen and Zhanglîhuâ Katô. Female initiation, shamanism and bear cult in a Daghuro-Mongolian Snow White precursor]. Fabula (in German). 49 (3–4): 288–324. doi:10.1515/FABL.2008.022. S2CID 161591972.

- Schmidt, Sigrid (1 December 2008). "Snow White in Africa". Fabula. 49 (3–4): 268–287. doi:10.1515/FABL.2008.021. S2CID 161823801.

- Nutt, Alfred. "The Lai of Eliduc and the Märchen of Little Snow-White". In: Folk-Lore Volume 3. London: David Nutt. 1892. p. 30.

- D'Aronco, Gianfranco. Le Fiabe Di Magia In Italia. Udine: Arti Grafiche Friulane, 1957. pp. 88-92.

- Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. pp. 156–157.

- Liungman, Waldemar. Die Schwedischen Volksmärchen: Herkunft und Geschichte. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2022 [1961]. p. 200. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783112618004-004

- Pino Saavedra, Yolando. Folktales of Chile. University of Chicago Press, 1967. p. 268.

- Kawan, Christine Shojaei (2005–2006). "Innovation, Persistence and Self-Correction: The Case of Snow White" (PDF). Estudos de Literatura Oral. 11–12: 239.

- Kawan, Christine Shojaei (2005–2006). "Innovation, Persistence and Self-Correction: The Case of Snow White" (PDF). Estudos de Literatura Oral. 11–12: 238–239.

- Tito Livio, Ab Urbe condita libri, VII, 26

- Francesco Zazzera, Della nobilta dell'Italia parte prima. Del signor D. Francesco Zazzera napoletano. Alla sereniss. e catol. maesta' del re Filippo 3. nostro signore, 1615, p. 16. English translated from original (italian of XVII century): «MARINO a very eloquent man, he was so versed in politics and the reasons of state that his opinion prevailing, in all the Consults and Councils, he rose in such a way that he had to sit in the Dogal Seat, after the death of Pietro Gradenigo, in which place ruled Doge 49th being created according to the truest opinion the year 1311. because others want it to be in 1303. where knowing himself (however given to the later spiritual, and contemplative life) not able, according to his desire to wait; on the contrary, unfortunately they seemed to him too strange and different from each other, detesting his first studies, and regretting having spent so many years madly; Moved by divine inspiration, the tenth month and tenth day of his rule, renouncing that dignity, he retired to his villa, where I refrain from the practices, conversations and of the century; some want him to die in the Religion of the Benedictines, and others in his ancient solitude, where from the beginning leading his life he chose to withdraw completely from the world: and so it was in truth, because advancing continuously in the wilderness, if I did, he almost lost his life A hermitic until 1320 who gave back the spirit to her Creator, she acquired Standofi a soura name of Saint; and offering the opportunity to more affectionate relatives, to originate a new surname. when he had grown up, seeing Zazzera wearing a hat up to his shoulders, as was mentioned by all of Zazzera, so Pietro, his brother, was the reason to take it away for his undertaking on the journey to the Embassy, where he was destined; and to his successors he later formed a new surname: which having done this briefly, the aforementioned Andrea Dandolo in the Chronicle of him mentions with the aforementioned words, adding advantageously, as at his own expense, he built the noble Temple of San Domenico; also endowing him with an income suitable for many fathers: all that was content to have his bones buried in the Church of S. Giovanni and Paolo, where his almost continuous residence was. » «MARINO huomo eloquentissimo, fu di maniera versato ne la Politica, e ne le ragioni di Stato che prevalendo la sua opinione, in tutte le Consulte, e Consegli, in maniera si sollevò, che gli ne toccò à seder nel Segio Dogale, dopo la morte di Pietro Gradenigo, nel qual luogo governò Doge 49° essendo creato secondo la più vera epinione l'an.1311.perche altri vogliono che fusse nel 1303.oue conoscendosi (dato però à la vita dopo spirituale, e contemplativa) non potere, conforme al suo desiderio attendere; anzi pur troppo strana parendogli, e diversa l'una da l'altra operazione, detestando i suoi primi studi, e pentito di haver cosi follemente Spesi tanti anni; mosso da divina ispirazione, il decimo mese, e decimo giorno del suo dominio, à quella dignità renunziando, si ritirò in una sua Villa, ove remoro da le pratiiche, conversazioni e del secolo; alcuni vogliono che morisse ne la Religion di Benedettini, ed altri ne l'antica sua solitudine, ove fin dal principio menar vita si elesse in tutto ritirata dal mondo: e così fu invero, perche avanzandosi continuamente ne la inselvatichir se medefimo, menò quasi vita Eremitica fino al 1320 che rendè lo spirito al suo Creatore, acqui Standofi un soura nome di Santo; e porgendo occasione à parenti più affezzionati, di originarsi nuovo coagnome. posciache cresciuta vedendosegli fina a le spalle una Zazzera, à capelliera, com'era da tutti de la Zazzera menzionato, così à Pietro suo fratello fu cagione di toglierla per sua Impresa nel viaggio de l'Ambasceria, ove fu destinato; ed à soccessori suoi dopò di formarlo nuovo cognome: che fatto ciò brevemente il sudetto Andrea Dandolo ne la sua Cronica accenna con le parole sudette, soggiungendo di vantaggio, come a proprie sue spese, edificasse il nobilissimo Tempio di San Domenico; dotandolo eziandio di rendita conveniente per molti padri: tutto che si contentasse far sepellir le sue ossa, ne la Chiesa di S. Giovanni, e Paolo, ov'era la sua quasi continua abitazione.»

- Lattanzio Bianco, "Discorso del dottor Lattanzio Bianco Napol. academico destillatore detto l'Acuto. Intorno al Teatro della nobiltà d'Italia, del dott. Flaminio De Rossi, oue particolarmente dell'origini, e nobiltà di Napoli, di Roma, e di Vinezia si ragiona", publisher Isidoro Facij & Bartolomeo Gobetti, year: 1607

- Giuliano e Marco Palmieri, I Regni Perduti dei Monti Pallidi, Verona, Cierre Edizione, 1996, SBN IT\ICCU\VIA\0079087

- Jessie Grimond, This Europe: Italy claims Snow White - and her seven dwarfs, in The Independent, mercoledì 29 gennaio 2014

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book XI, 289

- Graham Anderson, Fairytale in the ancient world, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0-415-23702-4

- De Nino, Antonio Usi e costumi abruzzesi Volume Terzo. Firenze: Tipografia di G. Barbèra 1883 pp. 253-257

- Gonzenbach, Laura Sicilianische Märchen vol. 1 Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann 1870 pp. 4-7

- Zipes, Jack The Robber with the Witch's Head: More Story from the Great Treasury of Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales Collected by Laura Gonzenbach New York and London: Routledge 2004 pp. 22-25

- De Gubernatis, Angelo Le Novellino di Santo Stefano Torino: Augusto Federico Negro 1869 pp. 32-35

- Crane, Thomas Frederick Italian Popular Tales Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company 1885 pp. 326-331

- Pitrè, Giuseppe Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliane Volume Secondo. Palermo: Luigi Pedone Lauriel 1875 pp. 39-44

- Zipes, Jack The Collected Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales of Giuseppe Pitré Volume 1 New York and London: Routledge 2009 pp. 260-263

- Imnbriani, Vittorio La Novellaja Fiorentina Livorno: Coi tipi di F. Vigo 1877 pp. 239-250

- Monnier, Marc Les Contes Populaires en Italie Paris: G. Charpentier 1880 pp. 341-357

- Schneller, Christian Märchen und Sagen aus Wälschtirol Innsbruck: Wagner 1867 pp. 55-59

- Coronedi Berti, Carolina Favelo bolognesi Monti 1883 pp. 8-10

- Sébillot, Paul Contes Populaires de la Haute-Bretagne Paris: G. Charpentier 1880 pp. 146-150

- Tatar, Maria The Fairest of Them All: Snow White and Other 21 Tales of Mothers and Daughters Harvard University Press 2020 pp. 89-93

- Sébillot, Paul Contes des Landes et des grèves Rennes: Hyacinthe Caillière 1900 pp. 144-152

- Cadic, François Contes et légendes de Bretagne Tome Second Rennes: Terre de Brume University Press 1999 pp. 293-299

- Morin, Louis Revue des Traditions Populaires Volume 5 Paris: J. Maisonneuve 1890 pp. 725-728

- Massignon, Geneviève Contes Corses Paris: Picard 1984 pp. 169-171

- de Meyere, Victor (1927). "CLXXX. Sneeuwwitje". De Vlaamsche vertelselschat. Deel 2 (in Dutch). Antwerpen: De Sikkel. pp. 272–279. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- Roelans, J (1924). "XLI. Mauricia". In de Mont, Pol; de Cock, Alphons (eds.). Wondervertelsels uit Vlaanderen (in Dutch) (2 ed.). Zutphen: W. J. Thieme & CIE. pp. 313–319. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- Lox, Harlinda Flämische Märchen Munich: Diederichs 1999 p. 36 nº 11

- Milá y Fontanals, Manuel Observaciones sobre la poesía popular Barcelona: Imprenta de Narciso Ramirez 1853 pp. 184-185

- Maspons y Labrós, Francisco Lo Rondallayre: Quentos Populars Catalans Vol. II Barcelona: Llibrería de Álvar Verdaguer 1871 pp. 83-85

- Nogués y Milagro, Romualdo Cuentos para gente menuda Madrid: Imprenta de A. Pérez Dubrull 1886 pp. 91-96

- Alcover, Antoni Maria Aplec de Rondaies Mallorquines S. Galayut (1915), pp. 80-92

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos Populares Españoles Standford University Press 1924, pp. 227-230

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos Populares Españoles Standford University Press 1924, pp. 230-231

- Llano Roza de Ampudia, Aurelio Cuentos Asturianos Recogidos de la Tradición Oral Madrid: Cario Ragio 1925, pp. 91-92

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos populares de Castilla y León Volumen 1 Madrid: CSIC 1987, pp. 331-334

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos populares de Castilla y León Volumen 1 Madrid: CSIC 1987, pp. 334-336

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos populares de Castilla y León Volumen 1 Madrid: CSIC 1987 pp. 337-342

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio Cuentos populares de Castilla y León Volumen 1 Madrid: CSIC 1987, pp. 342-346

- Zipes, Jack The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company 2013, pp. 580-582

- Jacobs, Joseph Celtic Fairy Tales London: David Nutt 1892 pp. 88-92

- Bruford, Alan and Donald A. MacDonald Scottish Traditional Tales Edinburgh: Polygon 1994 pp. 98-106

- Briggs, Katharine Mary A Dictionary of British Folktales in the English Language London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1970 pp. 494-495

- Winter, Mathias Danske folkeeventyr 1823 pp. 40-47

- Tang Kristensen, Evald Æventyr fra Jylland Vol. III Kjobehavn: Trykt hos Konrad Jorgensen i Kolding 1895 pp. 273-277

- Badman, Stephen Folk and Fairy Tales from Denmark vol. 1 2015 pp. 263-267

- Sanavio, Annuska Palme Fiabe popolari svedesi Milano: Rizzoli 2017 Tale nº 7

- Carnoy, Henri et Nicolaides, Jean Traditions populaires de l'Asie Mineure Paris 1889 pp. 91-106

- Megas, Georgios A. Folktales of Greece Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press pp. 106-113 1970

- Hahn, Johann Georg von Griechische und Albanesische Märchen Zweiter Theil Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann 1864 pp. 134-143

- Dozon, Auguste Contes Albanais Paris: Ernst Leroux 1881 pp. 1-6

- Kawan, Christine Shojaei (2008). "A Brief Literary History of Snow White". Fabula. 49 (3–4): 325–342. doi:10.1515/FABL.2008.023. S2CID 161939712.

- "Старая погудка на новый лад: Русская сказка в изданиях конца XVIII века". Б-ка Рос. акад. наук. Saint Petersburg: Тропа Троянова, 2003. pp. 214-218 (text), 358 (classification). Полное собрание русских сказок; Т. 8. Ранние собрания.

- Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A.N. Afanas'ev Volume II University Press of Mississippi 2015 nº 211

- Löwis of Menar, August von Russische Volksmärchen Jena: Eugen Diederichs 1927 pp. 123-134

- Schott, Arthur und Albert Rumänische Volkserzählungen aus dem Banat Bukarest: Kriterion 1975 pp. 34-42

- Fortier, Alcée. Louisiana Folk-Tales. Memoirs of the American Folk-Lore Society. Vol. 2. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. 1895. pp. 56-61.

- "coaccess". apps.crossref.org. doi:10.4159/9780674245822-013. S2CID 242168546. Retrieved 2023-06-17.