Solomon, King of Hungary

Solomon, also Salomon (Hungarian: Salamon; 1053–1087) was King of Hungary from 1063. Being the elder son of Andrew I, he was crowned king in his father's lifetime in 1057 or 1058. However, he was forced to flee from Hungary after his uncle, Béla I, dethroned Andrew in 1060. Assisted by German troops, Solomon returned and was again crowned king in 1063. On this occasion he married Judith, sister of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. In the following year he reached an agreement with his cousins, the three sons of Béla I. Géza, Ladislaus and Lampert acknowledged Solomon's rule, but in exchange received one-third of the kingdom as a separate duchy.

| Solomon | |

|---|---|

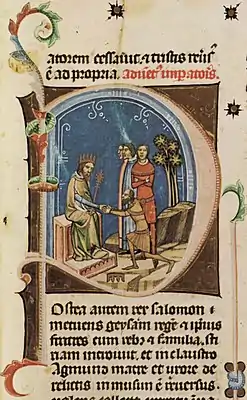

.jpg.webp) Solomon (Chronica Hungarorum) | |

| King of Hungary | |

| Reign | 1063–1074 |

| Coronation | 1057 or 1058 1063 |

| Predecessor | Béla I |

| Successor | Géza I |

| Born | 1053 |

| Died | 1087 Bulgaria theme (Byzantine Empire) |

| Spouse | Judith of Swabia |

| Dynasty | Árpád dynasty |

| Father | Andrew I of Hungary |

| Mother | Anastasia of Kiev |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

In the following years, Solomon and his cousins jointly fought against the Czechs, the Cumans and other enemies of the kingdom. Their relationship deteriorated in the early 1070s and Géza rebelled against him. Solomon could only maintain his rule in a small zone along the western frontiers of Hungary after his defeat in the Battle of Mogyoród on 14 March 1074. He officially abdicated in 1081, but was arrested for conspiring against Géza's brother and successor, Ladislaus.

Solomon was set free during the canonization process of the first king of Hungary, Stephen I, in 1083. In an attempt to regain his crown, Solomon allied with the Pechenegs, but King Ladislaus defeated their invading troops. According to a nearly contemporaneous source, Solomon died on a plundering raid in the Byzantine Empire. Later legends say that he survived and died as a saintly hermit in Pula (Croatia).

Early life

Solomon was a son of King Andrew I of Hungary and his wife, Anastasia of Kiev.[1] His parents were married in about 1038.[2] He was born in 1053[3] as his parents' second child and eldest son.[4]

His father had him crowned king in 1057 or 1058.[4][5] Solomon's coronation was a fundamental condition of his engagement to Judith, a sister of King Henry IV of Germany.[4][6] Their engagement put an end to the more than ten-year-long period of armed conflicts between Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire.[4][7][8] However, Solomon's coronation provoked his uncle, Béla, who had until that time held a strong claim to succeed his brother Andrew according to the traditional principle of seniority.[5][6][8] Béla had, since around 1048, administered the so-called ducatus or duchy, which encompassed one-third of the kingdom.[9]

.jpg.webp)

According to the Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle, a 14th-century chronicle:

Because carnal love and ties of blood are wont to prove a hindrance to truthfulness, in King Andreas love for his son overcame justice, so that he broke the treaty of his promise, which in kings should not be; in the twelfth year of his reign, when he was worn out with age, he caused his son Salomon, who was still a child of five years, to be anointed and crowned king over all Hungary. He pretended that he did this to prevent injury to his kingdom, for the Emperor would not have given his daughter to his son Salomon unless he had crowned him. When therefore they sang at Salomon's coronation: "Be lord over thy brethren," and it was told to Duke Bela by an interpreter that the infant Salomon had been made king over him, he was greatly angered.[10]

According to the Illuminated Chronicle, in order to secure Solomon's succession, his father arranged a meeting with Duke Béla at the royal manor in Tiszavárkony.[6][7] The king proposed that his brother choose between a crown and a sword (which were the symbols of royal and ducal power, respectively), but had previously commanded his men to murder the duke if Béla picked the crown.[6][7]

The duke, whom a courtier had informed of the king's plan, chose the sword, then left Hungary after the meeting.[6][7] He sought the assistance of Duke Boleslaus the Bold of Poland and returned with Polish reinforcements.[5][8] Béla emerged the victor in the ensuing civil war, during which Solomon's father was mortally injured in a battle.[8] Solomon and his mother fled to the Holy Roman Empire and settled in Melk in Austria.[4][8][11]

Béla was crowned king on 6 December 1060,[5] but the young German king's advisors, who were staunch supporters of Solomon (the fiancé of their monarch's sister), refused to conclude a peace treaty with him.[12] In the summer of 1063, the assembly of the German princes decided to invade Hungary in order to restore Solomon.[13] Solomon's uncle died in an accident on 11 September, before the imperial army arrived.[14] His three sons—Géza, Ladislaus and Lampert—left for Poland.[11]

Reign

Accompanied back to Hungary by German troops, Solomon entered Székesfehérvár without resistance.[4] He was ceremoniously "crowned king with the consent and acclamation of all Hungary"[15] in September 1063, according to the Illuminated Chronicle.[16] The same source adds that the German monarch "seated" Solomon "upon his father's throne",[15] but did not require him to take an oath of fealty.[4][5][16] Solomon's marriage with Henry IV's sister, Judith—who was six years older than her future husband[4]—also took place on this occasion.[12] Judith, along with her mother-in-law Anastasia, became one of her young husband's principal advisors.[3]

Solomon's three cousins - Géza and his brothers - returned after the German troops had been withdrawn from Hungary.[16] They arrived with Polish reinforcements and Solomon sought refuge in the fortress of Moson at the western border of his kingdom.[17] The Hungarian prelates began to mediate between them in order to avoid a new civil war.[16]

Solomon and his cousins eventually reached an agreement, which was signed in Győr on 20 January 1064.[5] Géza and his brothers acknowledged Solomon as lawful king, and Solomon granted them their father's one-time ducatus.[16][18] As a token of their reconciliation, Duke Géza put a crown on Solomon's head in the cathedral of Pécs on Easter Sunday.[16][18] Their relationship remained tense; when the cathedral burned down during the following night, they initially accused each other of arson.[18] The episode is described in the Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle as follows:

[Sudden] flames seized that church and the palaces and all nearby buildings, and they collapsed in one devastating conflagration. Everyone was gripped with fear at the shock of the roaring flames and the terrible shattering of the bells as they fell from the towers; and none knew where to turn. The King and the Duke were in an amazed stupor; terrified by the suspicion of foul work, each went his separate way. In the morning they were apprised through faithful messengers that in truth there had not been on either side any evil intention of treachery, but that the fire had been happening of chance. The King and the Duke came together again in the goodness of peace.[19]

The king and his cousins closely cooperated in the period between 1064 and 1071.[20][21] Both Solomon and Géza were, in 1065 or 1066, present at the consecration of the Benedictine Zselicszentjakab Abbey, established by Palatine Otto of the Győr clan, a partisan of the king.[21][22] They invaded Bohemia together after the Czechs had plundered the region of Trencsén (present-day Trenčín, Slovakia) in 1067.[20][23] During the following year, nomadic tribes broke into Transylvania and plundered the regions, but Solomon and his cousins routed them at Kerlés (present-day Chiraleş, Romania).[20][24] The identification of the marauders is uncertain: the Annales Posonienses and Simon of Kéza write of Pechenegs, the 14th-century Hungarian chronicles refer to Cumans, and a Russian chronicle mentions the Cumans and the Vlachs.[25]

Pecheneg troops pillaged Syrmia (now in Serbia) in 1071.[20][23] As the king and the duke suspected that the soldiers of the Byzantine garrison at Belgrade incited the marauders against Hungary, they decided to attack the fortress.[20] The Hungarian army crossed the river Sava, although the Byzantines "blew sulphurous fires by means of machines"[26] against their boats.[27] The Hungarians took Belgrade after a siege of three months.[28] However, the Byzantine commander, Niketas, surrendered the fortress to Duke Géza instead of the king; he knew that Solomon "was a hard man and that in all things he listened to the vile counsels of Count Vid, who was detestable in the eyes both of God and men",[29] according to the Illuminated Chronicle.[30]

Division of the war-booty caused a new conflict between Solomon and his cousin, because the king granted only a quarter of the booty to the duke, who claimed its third part.[31] Thereafter the duke negotiated with the Byzantine Emperor's envoys and set all the Byzantine captives free without the king's consent.[32] The conflict was further sharpened by Count Vid; the Illuminated Chronicle narrates how the count incited the young monarch against his cousins by saying that as "two sharp swords cannot be kept in the same scabbard", so the king and the duke "cannot reign together in the same kingdom".[33] [34]

The Byzantines reoccupied Belgrade in the next year.[35] Solomon decided to invade the Byzantine Empire and ordered his cousins to accompany him.[34][36] Only Géza joined the king; his brother, Ladislaus, remained with half of their troops in the Nyírség.[34][36] Solomon and Géza marched along the valley of the river Great Morava as far as Niš.[35][27] Here the locals made them "rich gifts of gold and silver and precious cloaks"[37] and Solomon seized the arm of Saint Procopius of Scythopolis.[35][27] He donated the relic to the Orthodox monastery of Syrmium (present-day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia).[35][27]

After their return from the campaign, both Solomon and Géza began to make preparations for their inevitable conflict and were seeking assistance from abroad.[38] They concluded a truce, which was to last "from the feast of St Martin until the feast of St George", from 11 November 1073 until 24 April 1074.[35] However, Solomon chose to attack his cousin as soon as the German troops sent by his brother-in-law arrived in Hungary.[38] The royal army crossed the river Tisza and routed the troops of Géza, who had been abandoned by many of his nobles before the battle, at Kemej on 26 February 1074.[38][39]

A strong army soon arrived in Hungary, headed by Géza's brother-in-law, Duke Otto I of Olomouc.[39] In the decisive battle, which was fought at Mogyoród on 14 March 1074, Solomon was defeated and forced to flee from the battlefield.[39]

Abdication

After the battle of Mogyoród, Duke Géza's soldiers pursued Solomon and his men "from dawn to dusk",[40] but they managed to take refugee in Moson, where his mother and wife had been staying.[41] According to the Illuminated Chronicle, the queen mother blamed her son for the defeat, which filled Solomon with so much anger that he wanted to "strike his mother in the face".[42] His wife held him back by catching his hand.[41]

Thereafter, Solomon preserved only Moson and the nearby Pressburg (Bratislava, Slovakia). Other parts of the kingdom accepted the rule of Géza, who had been proclaimed king after his victory.[43][44]

Solomon sent his envoys to Henry IV and promised "six of the strongest fortified cities in Hungary" if his brother-in-law would help him to depose Géza.[45] He was even ready to accept the German monarch's suzerainty.[43]

Henry IV invaded Hungary in August.[45] He marched as far as Vác, but soon withdrew from Hungary without defeating Géza.[46] Nevertheless, the German invasion strengthened Solomon's rule in the region of his two fortresses,[45][46] where he continued to exercise all royal prerogatives, including coinage.[41] His mother and wife left him and followed Henry IV to Germany.[41] According to Berthold of Reichenau's Chronicle:

That summer [Henry IV] undertook an expedition into Hungary to help King Salomon, who also because of his insolent and shameful crimes had been deposed from his office by his father's brother (sic) and the other magnates of the kingdom, for whose counsels he cared little. [Henry IV], however, was able to achieve nothing of what he wished there, namely to restore Salomon. Finally, bringing back his sister, Queen Judith, the wife of Salomon, he returned home to Worms[47]

Solomon attempted to convince Pope Gregory VII to support him against Géza.[48] However, the pope condemned him for having accepted his kingdom "as a fief from the king of the Germans"[49] and claimed suzerainty over Hungary.[50] Thereafter it was Henry IV's support which enabled Solomon to resist Géza's all attempts at taking Moson and Pressburg.[51] The German monarch even sent one of his main opponents, Bishop Burchard II of Halberstadt, into exile to Solomon in June 1076.[52] Solomon's wife, Queen Judith, who was about to return to her husband, undertook to take the imprisoned bishop to Hungary, but the prelate managed to escape.[52]

Géza decided to start new negotiations with Solomon.[53] However, he died on 25 April 1077 and his partisans proclaimed his brother, Ladislaus, king.[54] The new king occupied Moson in 1079, thus Solomon could preserve only Pressburg.[55] In 1080[55] or 1081,[51] the two cousins concluded a treaty, according to which Solomon acknowledged Ladislaus as king in exchange for "revenues sufficient to bear the expenses of a king".[56][57]

Later life

Solomon did not give up his ambitions even after his abdication. He was arrested for plotting against his cousin,[57][58] then held in captivity in Visegrád.[57] He was released "on the occasion of the canonization of King St. Stephen and the blessed Emeric the confessor"[59] around 17 August 1083.[58][55] According to Hartvik's Legend of King Saint Stephen, King Ladislaus ordered Solomon's release, because nobody could open the grave of the saintly king while Solomon was held in captivity.[60]

Having been liberated, Solomon first visited his wife in Regensburg, "although she was not grateful for this",[61] according to the nearly contemporaneous Bernold of St Blasien.[51] From Germany, Solomon fled to the "Cumans"—in fact Pechenegs, according to the historians Gyula Kristó and Pál Engel—who were dwelling in the regions east of the Carpathian Mountains and north of the Lower Danube.[51][58] Solomon promised one of their chiefs, Kutesk, that "he would give him the right of possession over the province of Transylvania and would take his daughter as wife"[59] if Kutesk and his people would help him to regain his throne.[51][60] They invaded the regions along the Upper Tisza "with a great multitude"[59] of the "Cumans", but King Ladislaus routed and forced them to withdraw from Hungary.[60][62]

At the head of "a large contingent of Dacians"[63] (Hungarians), Solomon joined a huge army of Cumans and Pechenegs who invaded the Byzantine Empire in 1087.[64] The Byzantines routed the invaders in the mountains of Bulgaria.[64] Solomon seems to have died fighting in the battlefield, because Bernold of St. Blasien narrates that he "died courageously after an incredible slaughter of the enemy after he bravely undertook an enterprise against the King of the Greeks" in 1087.[65][66]

Reports of later sources prove that Solomon became the subject of popular legends.[67] For instance, the Illuminated Chronicle writes that Solomon "repented of his sins, so far as human understanding may reach" after the battle, and passed the last years of his life "in pilgrimage and prayer, in fastings and watchings, in labour and contrition".[68][66][67] According to these sources, Solomon died in Pula on the Istrian Peninsula[60] where he was venerated as a saint.[69] However, he was never officially canonized.[67] His alleged tombstone is now in a local museum.[69] Simon of Kéza wrote in his Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum:

[Solomon] was now completely at a loss, and after returning to his queen at Admont he spent a few days with her before returning to Székesfehérvár in monk's habit. There, the story goes, his brother (sic) Ladislas was distributing alms to the poor with his own hands on the porch of the church of the Blessed Virgin, and Solomon was among the recipients. When Ladislas looked closely he realised who it was. After the distribution was over Ladislas made careful inquiries. He intended Solomon no harm, but Solomon assumed he did, and quit Székesfehérvár, making for the Adriatic. There he passed the rest of his days in complete poverty in a city named Pula; he died in destitution and was buried there, never having returned to his wife.[70]

Family

| Ancestors of Solomon of Hungary[71][72] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Solomon's wife, Judith, who was born in 1048, was the third daughter of Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor and his second wife, Agnes de Poitou.[73] Their wedding took place in Székesfehérvár in June 1063.[4] The marriage remained childless.[74] They first separated from each other around 1075.[41] According to Bernold of St. Blasien, neither Solomon nor his wife had "kept the marriage contract: on the contrary, they had not been afraid, in opposition to the apostle, to defraud each other."[75][51] Having been informed of Solomon's death, Judith married Duke Władysław I Herman of Poland in 1088.[74] In contrast with all contemporaneous sources, the late 13th-century Simon of Kéza writes that Judith "spurned all suitors" after her husband's death, although "many princes in Germany sought her hand".[76][74]

The following family tree presents Solomon's ancestors and some of his relatives who are mentioned in the article.[71][73]

| a lady of the Tátony clan | Vazul | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Henry III | Agnes of Poitou | Anastasia | Andrew I | Béla I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Henry IV | Judith | Solomon | 2 children | Géza I | Ladislaus I | Lampert | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kings of Hungary (from 1095) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 69, 87.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 69.

- Makk 1994, p. 77.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 87.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 26.

- Engel 2001, p. 31.

- Kontler 1999, p. 60.

- Robinson 1999, p. 35.

- Engel 2001, pp. 30–31.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 64.91), p. 115.

- Kontler 1999, p. 61.

- Robinson 1999, p. 53.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 78.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, pp. 80–81.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 69.97), p. 117.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 81.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 88.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 89.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 70.99), p. 118.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 82.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 90.

- Engel 2001, pp. 39, 44.

- Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 89.

- Curta 2006, p. 251.

- Spinei 2009, p. 118.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 74.104), p. 119.

- Curta 2006, p. 252.

- Stephenson 2000, p. 141.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 77.109), p. 120.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 83.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, pp. 83–84.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 91.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 78.110), p. 121.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 84.

- Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 90.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 92.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 79.112), p. 121.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 93.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 86.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 85.121), p. 124.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 94.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 87.123), p. 125.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 87.

- Bartl et al. 2002, p. 27.

- Robinson 1999, p. 99.

- Engel 2001, p. 32.

- Berthold of Reichenau, Chronicle (Second Version) (year 1074), p. 131.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 88.

- Pope Gregory VII's letter to King Solomon of Hungary, claiming suzerainty over that kingdom, p. 48.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, pp. 88–89.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 95.

- Robinson 1999, p. 152.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, pp. 90–91.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 92.

- Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 92.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 94.133), p. 128.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 93.

- Engel 2001, p. 33.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 95.134), p. 128.

- Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 94.

- Bernold of St Blasien, Chronicle (year 1084), p. 273.

- Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 93.

- Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (7.1.), p. 217.

- Curta 2006, p. 300.

- Bernold of St Blasien, Chronicle (year 1087), p. 290.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 95–96.

- Klaniczay 2002, p. 148.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 96.136), p. 129.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 97.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 2.61), pp. 135–137.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. Appendices 1–2.

- Vernadsky 1948, pp. 39, 57.

- Robinson 1999, p. 19.

- Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 96.

- Bernold of St Blasien, Chronicle (year 1084), p. 274.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 2.61), p. 137.

Sources

Primary sources

- Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (Translated by E. R. A. Sewter) (1969). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044958-7.

- "Bernold of St Blasien, Chronicle" (2008). In Robinson, I. S. Eleventh-Century Germany: The Swabian Chronicles. Manchaster University Press. pp. 245–337. ISBN 978-0-7190-7734-0.

- "Berthold of Reichenau, Chronicle: Second Version" (2008). In Robinson, I. S. Eleventh-Century Germany: The Swabian Chronicles. Manchaster University Press. pp. 108–244. ISBN 978-0-7190-7734-0.

- "Pope Gregory VII's letter to King Solomon of Hungary, claiming suzerainty over that kingdom". In The Correspondence of Pope Gregory: Selected Letters from the Registrum (Translated with and Introduction and Notes by Ephraim Emerton). Columbia University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-231-09627-0.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary sources

- Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). "Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301" [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]. In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Klaniczay, Gábor (2002). Holy Rulers and Blessed Princes: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42018-0.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kosztolnyik, Z. J. (1981). Five Eleventh Century Hungarian Kings: Their Policies and their Relations with Rome. Boulder. ISBN 0-914710-73-7.

- Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói [Rulers of the House of Árpád] (in Hungarian). I.P.C. Könyvek. ISBN 963-7930-97-3.

- Makk, Ferenc (1994). "Salamon". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 591. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Robinson, I. S. (1999). Henry IV of Germany, 1056–1106. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54590-0.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02756-4.

- Vernadsky, George (1948). A History of Russia, Volume II: Kievan Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01647-6.

.svg.png.webp)