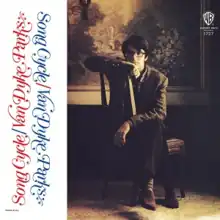

Song Cycle (album)

Song Cycle is the debut album by American recording artist Van Dyke Parks, released in November 1967 by Warner Bros. Records. With the exception of three cover songs, Song Cycle was written and composed by Parks, while its production was credited to Warner Bros. staff producer Lenny Waronker.

| Song Cycle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | November 1967 | |||

| Recorded | 1967 | |||

| Studio | Sunset Sound Recorders, Hollywood | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 32:39 | |||

| Label | Warner Bros. | |||

| Producer | Lenny Waronker | |||

| Van Dyke Parks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Song Cycle | ||||

| ||||

The album draws from a number of American popular music genres, including bluegrass, ragtime, and show tunes, and frames classical styles in the context of 1960s pop music.[5] The material utilizes unconventional song structures, and lyrically explores American history and culture, reflecting Parks' history working in both the film and music industries of Southern California.

Upon its release, Song Cycle was largely acclaimed by critics despite lukewarm sales, and later gained status as a cult album. In 2017, Song Cycle was ranked the 93rd greatest album of the 1960s by Pitchfork.[6]

Background

In Los Angeles during the mid-1960s, Van Dyke Parks became known as an in-demand session pianist, working with such artists as The Byrds, Tim Buckley, and Paul Revere & the Raiders. At the same time, he had been unsatisfied with contemporary pop music and its increasing submissiveness to the British invasion, going so far as to say, "apart from Pet Sounds I didn't find anything striking coming out of the United States."[7] Wanting to give "an American experience which would be uniquely disassociable from the Beatles/British pop viewpoint," he was involved with numerous works that would indulge his interest in Depression-era American pop and folk music, such as co-writing and arranging much of Harpers Bizarre's second album Anything Goes; releasing his own singles "Come to the Sunshine", "Number Nine", and most notably providing lyrical content to the Beach Boys' album Smile.[7]

For his collaborations with Brian Wilson, Parks was signed as a recording artist by Warner Bros. Records.[8] The label reportedly expected that Parks could deliver a smashing commercial success on par with the Beach Boys at that time.[9] During this epoch, Parks visited Frank Sinatra, who was dispirited by the rise of rock music, and was considering retirement. To help alleviate this, Parks pitched his brother Carson's song "Somethin' Stupid" as a duet for Sinatra and his daughter Nancy. Reportedly on Lee Hazlewood's advice, Sinatra recorded "Somethin' Stupid", and it became his first million-selling single. This bought credit for Parks at Warner Bros, and they proceeded to fund Parks's one single: an instrumental cover of Donovan's 1965 song "Colours". It was credited to "George Washington Brown"—a fictitious pianist from South America—to protect his family from the potential infamy of his "musical criminology".[10] "Donovan's Colours" received an ecstatic two-page review by Richard Goldstein, which convinced the label of Parks's ability.[11]

After Parks signed a solo contract with Warner Bros, he formed part of a creative circle that came to include producer Lenny Waronker and songwriter Randy Newman.[12] Parks subsequently abandoned the Smile project, leaving the album forever unfinished by the Beach Boys.[13]

Recording

The album's sessions cost more than US$35,000 (exceeding US$290,000 today), making it one of the most expensive pop albums ever recorded up to that time — in 1967, the typical budget for a pop studio album was about $10,000 (US$90,000 today).[14] The producers were able to make early use of an eight-track professional reel-to-reel recorder, which was used to mix second generation four-track tape that had been transferred from another four-track recording for overdubs.[15] Parks has added that the bulk of the album was done "before Sgt. Pepper reared its ugly head", and that Randy Newman had written "Vine Street" especially for him.[16] Many Los Angeles recording facilities were used, not because of any particular sound preference, but to maximize studio time.[15] Song Cycle contained experimental production and recording methods, including varispeed and regenerated tape delay.[17] Audio engineer Bruce Botnick is credited for inventing the "Farkle" effect, an ingenious modification to a Sunset Sound Recorders echo box.[18] The Farkle effect was used most prominently on violins, harps, and the intro to "The All Golden", and involved very thin splicing tape folded like a fan attached to a tape overhead.[18]

Three-quarter-inch masking tape was creased in eighth-inch folds and wrapped like a fan around the capstan of an Ampex 300 full-track mono tape machine at 30ips. The tape then ran through the recorder and fluttered as the rubber capstan bounced, and, by bringing back the output of the farkle to the mix, Botnick was able to attain the sought-after effect while adding plenty of echo from the famed Sunset Sound chamber and delaying it further via an Ampex 200 three-track at 15ips.[19]

The album opens with a recording of guitarist Steve Young performing "Black Jack Davy", a 17th-century ballad.[20]

Release

The album had the provisional title Looney Tunes, a nod to the cartoons produced by Warner Brothers' film division.[21] According to Parks,

When I played the album for Joe Smith, the president of the label, there was a stunned silence. Joe looked up and said, "Song Cycle"? I said, "Yes," and he said, "So, where are the songs?" And I knew that was the beginning of the end. Warner held the album for a year. Then I met Jac Holzman, and after he listened to it, he went to Warner Brothers and said, "If you folks aren’t going to release this album, I will—how much do you want for it?" So they decided to put it out, grudgingly.[9]

Released in November 1967,[22][23] Parks later felt that the album hadn't turned out exactly as he wanted, noting: "An album with no songs was entirely unintentional", and considered the album more of a learning exercise, "made with a mindset about the importance of studio exploration."[14]

Reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[24] |

In his column for Esquire, music critic Robert Christgau felt that Song Cycle "does not rock" and had "serious reservations about [Parks'] precious, overwrought lyrics and the reedy way he sings them, but the music on this album is wonderful."[25] Warner Bros. press sheets advertised Song Cycle as "the most important, creative and advanced pop recording since Sgt. Pepper."[14] Although it received good reviews upon release, Song Cycle sold slowly, and took at least three years to pay for the original studio sessions.[26] AllMusic's Jason Ankeny has described the album as

an audacious and occasionally brilliant attempt to mount a fully orchestrated, classically minded work within the context of contemporary pop. As indicated by its title, Song Cycle is a thematically coherent work, one which attempts to embrace the breadth of American popular music; bluegrass, ragtime, show tunes – nothing escapes Parks' radar, and the sheer eclecticism and individualism of his work is remarkable. ...[T]he album is both forward-thinking and backward-minded, a collision of bygone musical styles with the progressive sensibilities of the late '60s; while occasionally overambitious and at times insufferably coy, it's nevertheless a one-of-a-kind record, the product of true inspiration.[5]

In response to the poor sales of the record after its release, Warner Bros. Records ran full page newspaper and magazine advertisements written by staff publicist Stan Cornyn that said they "lost $35,509 on 'the album of the year' (dammit)."[26] The ad said that those who actually purchased the album had likely worn their copies out by playing it over and over, and suggested that listeners send in worn out copies to Warner Bros. in return for two new copies, including one "to educate a friend with."[27] Incensed by the tactic, Parks accused Cornyn of trying to kill his career.[28] Excerpts from positive reviews were reprinted in these ads, which included statements written by the Los Angeles Free Press ("The most important art rock project"), Rolling Stone ("Van Dyke Parks may come to be considered the Gertrude Stein of the new pop music"), and The Hollywood Reporter ("Very esoteric").[27]

Many musicians cite the album as an influence, including producer and songwriter Jim O'Rourke.[29] O'Rourke worked with Parks and harpist Joanna Newsom on Newsom's record Ys. Joanna Newsom sought out the partnership with Van Dyke Parks after listening to Song Cycle.[30]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Van Dyke Parks, except where noted

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Vine Street" (Randy Newman) | 3:40 |

| 2. | "Palm Desert" | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Widow's Walk" | 3:13 |

| 4. | "Laurel Canyon Blvd" | 0:28 |

| 5. | "The All Golden" | 3:46 |

| 6. | "Van Dyke Parks" (public domain) | 0:57 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 7. | "Public Domain" | 2:34 |

| 8. | "Donovan's Colours" (Donovan Leitch) | 3:38 |

| 9. | "The Attic" | 2:56 |

| 10. | "Laurel Canyon Blvd" | 1:19 |

| 11. | "By the People" | 5:53 |

| 12. | "Pot Pourri" | 1:08 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 13. | "The Eagle And Me" (Harold Arlen/Yip Harburg) | 2:32 |

Notes

- "Van Dyke Parks" (credited as 'public domain') is actually an interpretation of "Nearer, My God, to Thee", "accompanied by the sound of rushing water".[24]

Personnel

- Van Dyke Parks – main performer, vocals

- Additional musicians and production staff

- Lenny Waronker – producer

- Ron Elliott, Dick Rosmini – guitar

- Jim Hendricks - lead vocal on "Van Dyke Parks"

- Misha Goodatieff – violin

- Virginia Majewski – viola

- Carl Fortina – accordion

- Nicolai Bolin, Vasil Crlenica, William Nadel, Allan Reuss, Leon Stewart, Tommy Tedesco – balalaika

- Don Bagley, Gregory Bemko, Chuck Berghofer, Harry Bluestone, Samuel Boghossian, Dennis Budimir, Joseph Ditullio, Jesse Ehrlich, Nathan Gershman, Philip Goldberg, Armand Kaproff, William Kurasch, Leonard Malarsky, Jerome Reisler, Red Rhodes, Trefoni Rizzi, Lyle Ritz, Joseph Saxon, Ralph Schaffer, Leonard Selic, Frederick Seykora, Darrel Terwilliger, Bob West – strings

- Gayle Levant – harp

- Norman Benno, Arthur Briegleb, Vincent DeRosa, George Fields, William Green, Jim Horn, Dick Hyde, Jay Migliori, Tommy Morgan, Ted Nash, Richard Perissi, Thomas Scott, Thomas Shepard – woodwind

- Billie J. Barnum, Gerri Engeman, Karen Gunderson, James and Vanessa Hendricks, Durrie and Gaile Parks, Julia E. Rinker, Paul Jay Robbins, Nik Woods – choir

- Hal Blaine, Gary Coleman, Jim Gordon, Earl Palmer – percussion

- Steve Young – folk ("Vine Street" introduction tape)

References

- Boyd, Brian (March 26, 1999). "Strange Vibrations". Irish Times.

- Grimstad, Paul (2007-09-04). "What is Avant-Pop?". Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Morris, Chris (July 19, 2003). "Billboard". Billboard. 115 (29): 36. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Hogwood, Ben (5 July 2012). "Spotlight: Van Dyke Parks reissues – Song Cycle, Discover America and The Clang Of The Yankee Reaper". MusicOMH. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Ankeny, Jason. Song Cycle at AllMusic. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- "The 200 Best Albums of the 1960s". Pitchfork. August 22, 2017.

- White, Timothy (February 1985). Musician Magazine.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Henderson 2010, p. 71.

- Kozinn, Allan (July 22, 2013). "'Smile' and Other Difficulties". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Lecture: Van Dyke Parks (New York, 2013)". Red Bull Music Academy. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "The Seldom Seen Kid". Mojo: 55–57. August 12, 2012. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013.

- Henderson 2010, pp. 53–56.

- Vosse, Michael (April 14, 1969). "Our Exagmination Round His Factification For Incamination of Work in Progress: Michael Vosse Talks About Smile". Fusion. Vol. 8.

- Lake 2010, pp. 78.

- Henderson 2010, p. 63.

- Claster, Bob (February 13, 1984). "A Visit With Van Dyke Parks". Bob Claster's Funny Stuff. bobclaster.com. Retrieved 1 August 2013. (Mirror on YouTube)

- Henderson 2010, p. 66.

- Henderson 2010, pp. 77–78.

- Buskin, Richard (December 2003). "CLASSIC TRACKS: 'Strange Days'". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Henderson 2010, p. 68.

- Henderson 2010, p. 27.

- White 1996, p. 279.

- Johnson, Pete (December 10, 1967). "Pop Music's Pilot Through the Aesthetic Shoals". Los Angeles Times. Calendar section, p. P1. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

...only one album, 'Song Cycle,' on Warner Bros. It was just released...

- Greene, Jayson (July 5, 2012). "Song Cycle review". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Christgau, Robert (June 1968). "Columns". Esquire. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- Splice Today article: "INTERVIEW: Van Dyke Parks."

- Henderson 2010.

- Goodman 1997, p. 79.

- "Interviewee's Favorite Albums". Perfect Sound Forever. furious.com. Archived from the original on 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- Davis, Erik (2006). ""Nearer the Heart of Things": Erik Davis profiles JOANNA NEWSOM". Arthur Magazine (25). Retrieved 4 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Goodman, Fred (1997). The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen and the Head-On Collision of Rock and Commerce. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-4562-1.

- Henderson, Richard (2010). Song Cycle. 33⅓. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2917-9.

- Lake, Kirk (2010). There Will Be Rainbows: A Biography of Rufus Wainwright. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-201871-7. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- VanderLans, Rudy (1999). Palm Desert. Emigre. ISBN 978-0-9669409-0-9. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- White, Timothy (1996). The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys, and the Southern Californian Experience. Macmillan. ISBN 0333649370.

External links

- 331⁄3 blog page: "Van Dyke Parks – Song Cycle, by Richard Henderson.

- Song Cycle (1978 Warner Bros. reissue) at Discogs