1983 Anchorage runway collision

On 23 December 1983, Korean Air Lines Flight 084 (KAL084), a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 performing a cargo flight, collided during its takeoff roll with SouthCentral Air Flight 59 (SCA59), a Piper PA-31-350, on runway 06L/24R (now 07L/25R) at Anchorage International Airport, as a result of the KAL084 flight crew becoming disoriented while taxiing in dense fog and attempting to take off on the wrong runway. Both aircraft were destroyed, but no fatalities resulted.[1][2][3][4][5]

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 23 December 1983 |

| Summary | Collision on runway due to fog and disorientation of the pilot onboard Flight 084 |

| Site | Anchorage International Airport, Anchorage, Alaska |

| Total fatalities | 0 |

| Total injuries | 6 |

| Total survivors | 12 (all) |

| First aircraft | |

The DC-10 involved in the accident, seen at Orly Airport in April 1981. | |

| Type | McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 |

| Operator | Korean Air Lines |

| IATA flight No. | KE084 |

| ICAO flight No. | KAL084 |

| Call sign | KOREAN AIR 084 |

| Registration | HL7339 |

| Flight origin | Anchorage International Airport, Anchorage, Alaska |

| Destination | Los Angeles International Airport, Los Angeles, California |

| Occupants | 3 |

| Passengers | 0 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 3 |

| Survivors | 3 (all) |

| Second aircraft | |

.jpg.webp) A PA-31-350 similar to that involved in the accident. | |

| Type | Piper PA-31-350 Navajo Chieftain |

| Operator | SouthCentral Air |

| IATA flight No. | XE59 |

| ICAO flight No. | SCA59 |

| Call sign | SOUTHCENTRAL 59 |

| Registration | N35206 |

| Flight origin | Anchorage International Airport, Anchorage, Alaska |

| Destination | Kenai Municipal Airport, Kenai, Alaska |

| Occupants | 9 |

| Passengers | 8 |

| Crew | 1 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 3 |

| Survivors | 9 (all) |

Accident

At 1215 Yukon Standard Time,[lower-alpha 1] Flight 59 was cleared from Anchorage to Kenai in accordance with its filed flight plan; however, clearance delivery told the pilot to expect a delay until 1244 due to the heavy fog covering the airport, so the pilot shut down the aircraft and he and his passengers deplaned temporarily. After reboarding and recontacting the tower at 1234, Flight 59 was delayed for about an hour at its parking location due to the continued dense fog, before finally requesting and receiving a taxi clearance around 1339 as visibility began to improve. SCA 59 arrived at taxiway W-3 (which connects the main east–west taxiway to the approach end of runway 6L) at 1344, holding short of runway 6L until the runway visual range (RVR) reached 1,800 ft (550 m), the minimum required for the flight to take off.[1][2][3][5][lower-alpha 2]

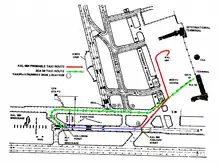

At 1357, the Anchorage ground controller cleared Korean Air Lines Flight 084 to taxi for a departure on either runway 6R or runway 32; the flight crew chose runway 32. The flight crew's selection of runway 32 was contrary to Korean Air Lines' operating specifications, as these required a visibility of at least one-quarter mile for takeoff on runway 32 at Anchorage, while the visibility at the time was only one-eighth of a mile.[1][2][5][lower-alpha 3] (The National Transportation Safety Board [NTSB], which investigated the accident, was unable to determine why the flight crew chose runway 32 instead of runway 6R, in part because the aircraft's cockpit voice recorder (CVR) was never recovered.)[1][2] The proper taxi route from the north apron (where the DC-10 was parked) to runway 32 would have involved taxiing south to the east–west taxiway, then making a right turn onto the east–west taxiway and following it to the threshold of runway 32 before turning right again onto the runway. However, the flight instead taxied southwest on taxiway W-1 to runway 6L/24R and lined up on the latter runway, facing west.[3] The heavy fog prevented the ground controller from being able to see the flight's taxi route[3] and impaired the KAL084 flight crew's ability to navigate around the airport;[2][lower-alpha 4] additionally, some of the lighted taxiway and runway designation signs along the flight's course were partially or fully burned out, making the signs less visually conspicuous and harder to see, and the intersections of taxiway W-1 with the east–west taxiway and with runway 6L/24R lacked signage to indicate the identity of either taxiway (the latter deficiency was rectified after the accident).[1][5] The height above the ground of the DC-10's flight deck, about 30 ft (9.1 m), exacerbated the flight crew's difficulties, as it increased the slant range from the crew's eyes to the runway and taxiway signage and pavement markings.[1][2] After taxiing into position on what the KAL084 flight crew thought was runway 32, the captain expressed some uncertainty that the aircraft was on the correct runway, and briefly considered switching to runway 6R, but, reassured by his first officer's certainty that they were on runway 32, the captain reported at 1403 that Flight 084 was holding in position on runway 32, and, at 1404, the flight was cleared for takeoff. At no time did the flight crew, despite the uncertainty expressed by the captain, attempt to use their instruments to verify that the heading of the runway they were on matched that of runway 32; the NTSB was unable to determine the reason for this omission.[1][2][5]

At 1405:28, the Anchorage tower controller cleared SCA59 to taxi into position and hold on runway 6L, as the RVR had risen to the required 1,800 feet; 50 seconds later, at 1406:18, KAL084 radioed that it was starting its takeoff roll.[5] Shortly afterwards, the pilot of SCA59 saw headlights approaching, which he initially assumed to be from a truck on the runway. After realizing that the lights were in fact from an aircraft on its takeoff roll, he ducked down low and yelled for his passengers to do the same.[1][2][4] Meanwhile, the captain of Flight 084, seeing the PA-31 in his aircraft's path, applied up elevator and left rudder, lifting the DC-10's nose landing gear off the ground and causing its main body gear (mounted on the aircraft's centerline between the left and right wing gear) to swing to the right; as a result, the PA-31's fuselage was straddled by the DC-10's body gear and left wing gear, instead of being struck head-on by the body gear (which would likely have resulted in fatalities on board the smaller aircraft).[1][2][5] After striking Flight 59, KAL084 continued off the end of the runway at far below flying speed,[lower-alpha 5] crashed through seven non-frangible towers supporting the runway 6L approach lighting system, came to rest 1,434 ft (437 m) past the end of the runway, and immediately caught fire.[1][2][3][4][5][7]

.png.webp)

Three of the passengers on board SCA59 received minor injuries, while the remaining passengers and the pilot were uninjured, although the aircraft was destroyed by the impact (the left and right wings were sheared off by the DC-10's main landing gear, while the DC-10's nose gear caved in the right side of the cockpit roof and then tore off part of the PA-31's vertical stabilizer);[1][3][5][7] the three flight crew of KAL084 were seriously injured by impact forces, but managed to escape their aircraft before it was consumed by fire.[1][2][3][5] (Some initial media reports erroneously listed seven injuries among the SCA59 occupants and none aboard KAL084.)[7]

Other runway collisions in December 1983

Coincidentally, the Anchorage accident was one of four runway collisions involving large air carrier aircraft in December 1983, all of which occurred in conditions of restricted visibility:[1]

- On 7 December, the Madrid runway disaster occurred when an Iberia Boeing 727 on its takeoff roll collided in fog with an Aviaco Airlines McDonnell Douglas DC-9, resulting in 93 fatalities and the destruction of both aircraft.[1][8][lower-alpha 6]

- On 19 December, a Japan Air Lines Boeing 747 landing on runway 6R at Anchorage in fog struck an airport truck taking runway friction measurements, destroying the truck and severely injuring its driver while slightly damaging the 747.[1][3][4][7][9]

- On 20 December, Ozark Air Lines Flight 650, a DC-9, struck and destroyed a snow sweeper while landing at Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in a snowstorm, breaking off the aircraft's right wing and killing the driver of the snow sweeper.[1][9]

See also

- Runway safety

- Linate Airport disaster, another runway collision in fog due to a pilot taking an incorrect taxi route

- 1990 Wayne County Airport runway collision, another runway collision in fog due to a pilot taking an incorrect taxi route

- Madrid runway disaster, another December 1983 runway collision in fog due to a pilot taking an incorrect taxi route

- Comair Flight 5191, another accident involving a flight crew taking off on a wrong runway when this could have been avoided by use of instruments to crosscheck the runway heading

- Singapore Airlines Flight 006, a case where a crew attempted a takeoff on a runway closed for construction, due, in part, to reduced visibility

Notes

- Alaska switched from four time zones to two on 30 October 1983, when the Yukon Time Zone (UTC−09:00 in winter and UTC−08:00 in summer), formerly used only in the city of Yakutat, was expanded to cover most of the state, including the city and airport of Anchorage. The Yukon Time Zone was renamed the Alaska Time Zone at the end of November 1983; see Time in Alaska for more information. The time in effect on the day of the accident would thus technically have been Alaska Standard Time; however, the NTSB report still uses the term "Yukon Standard Time".

- At the time of the 1983 accident, the airport's three runways were numbered 6L/24R, 6R/24L, and 14/32. As of 2021, these are now numbered 7L/25R, 7R/25L, and 15/33, respectively, as the runways' magnetic headings are different from their 1983 values due to changes in Anchorage's magnetic declination over time resulting from shifts in the earth's magnetic field.

- In contrast, a takeoff on runway 6R - the airport's primary instrument runway - would have required only that the transmissometers at the touchdown, midfield, and rollout zones of that runway were indicating an RVR of at least 600 feet; the runway 6R RVR was significantly better than this minimum, and, thus, KAL's operating specifications would have allowed a takeoff on this runway (but only on this runway).[1]

- Other flightcrews that day had also experienced difficulty finding their way around in the fog. In a postaccident interview, the SCA 59 pilot recalled that, while he was taxiing to runway 6L, a Japan Airlines aircraft had started to pull into taxiway W-3 behind him, temporarily confusing it for taxiway W-4 (which connected the western ends of the east-west taxiway and runway 6R/24L), before realizing their mistake and continuing on down the east-west taxiway;[1] in addition, airport safety personnel had had to assist in directing other aircraft that had become lost in the fog.[6]

- The intersection of taxiway W-1 and runway 6L/24R, where the DC-10 began its takeoff roll, is approximately three-quarters of the way along runway 24R, leaving only 2,400 ft (730 m) until the end of the runway. At the weight, air temperature, and field elevation applicable for KAL 084, it would have required a runway length of 8,150 ft (2,480 m) to take off, more than three times the actual length available. As a result, the DC-10, starting from where it did, could not have successfully taken off even had it not collided with the PA-31.[1][2][3][5]

- The NTSB's mention of this accident in the report on the Anchorage runway collision lists an greater number of fatalities for the Madrid accident than actually occurred, but is otherwise accurate.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

- "Korean Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30, HL7339, SouthCentral Air Piper PA-31-350, N35206, Anchorage, Alaska, December 23, 1983" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 9 August 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- J. Mac McClellan (May 1985). "Aftermath: Takeoff Collision". Flying. pp. 20–22. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "A Korean Air Lines DC-10 cargo plane, apparently trying..." United Press International. 23 December 1983. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "Officials investigate possible language barrier in crash". United Press International. 24 December 1983. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "Mishap With A Moral". The MAC Flyer. Military Airlift Command. January 1985. pp. 20–23. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- KOREAN AIR LINES COMPANY, LTD., Bum Hee Lee and Bong Hyun Cho, Appellants/Cross-Appellees, v. STATE of Alaska, Motorola, Inc., Employers Insurance of Wausau, a Wisconsin corporation, Applied Magnetics Corporation, a California corporation, and Granite State Insurance Company, a New Hampshire corporation, Appellees/Cross-Appellants., 779 P.2d 333 (Alaska 1 September 1989) ("Brantley, a safety officer for the airport, testified that he had to locate and lead other aircraft that had become lost in the fog.").

- Paul Jenkins (24 December 1983). "KAL cargo jet collides with passenger plane". The Desert Sun. No. 122. Associated Press. p. A3. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "TECHNICAL REPORT: Accident which occurred to aircraft McDonnell Douglas DC-9 and Boeing B-727-200, Registration EC-CGS and EC-CFJ, in Madrid-Barajas Airport, Spain" (PDF). Civil Aviation Accident Investigation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- "Aircraft Accident/Incident Summary Reports" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 30 September 1985. pp. 17–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

External links

- NTSB accident report (summary, PDF) - copy of PDF at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University

- Accident description (DC-10) at the Aviation Safety Network (archive)

- Accident description (PA-31) at the Aviation Safety Network Wikibase (archive)

- Footage of the accident scene on YouTube, narrated by an ARFF captain who responded to the crash

Lawsuits arising from the accident: