South African Army

The South African Army is the principal land warfare force of South Africa, a part of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), along with the South African Air Force, South African Navy and South African Military Health Service. The Army is commanded by the Chief of the Army, who is subordinate to the Chief of the SANDF.

| South African Army | |

|---|---|

Flag of the South African Army | |

| Founded | 1912[lower-alpha 1] |

| Country | |

| Branch | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size |

|

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa |

| Motto(s) | For The Motherland! |

| Anniversaries | 10 May |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Minister of Defence and Military Veterans | Thandi Modise |

| Chief of the Army | Lt Gen Lawrence Mbatha |

| Deputy Chief Army | Maj Gen Michael Ramantswana |

| Sergeant Major of the Army | Senior Chief Warrant Officer P.T. Tladi |

| Insignia | |

| Seal |  |

Formed in 1912, as the Union Defence Force in the Union of South Africa, through the amalgamation of the South African colonial forces following the unification of South Africa. It evolved within the tradition of frontier warfare fought by Boer Commando (militia) forces, reinforced by the Afrikaners' historical distrust of large standing armies.[2] Following the ascension to power of the National Party, the Army's long-standing Commonwealth ties were afterwards cut.

The South African Army was fundamentally changed by the end of Apartheid and its preceding upheavals, as the South African Defence Force became the SANDF. This process also led to the rank and age balance of the army deteriorating desperately, though this has greatly improved.

During its history, the South African Army has fought in a number of major wars, including the First and Second World Wars, Rhodesian Bush War, and the long and bitter Border War. The South African Army has also been involved in many peacekeeping operations such as in the Lesotho intervention, Central African Republic Civil War, and multiple counter-insurgencies in Africa; often under the auspices of the United Nations, or as part of wider African Union operations in Southern Africa. It also played a key role in controlling sectarian political violence inside South Africa during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

History

After the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, General Jan Smuts, the Union's first Minister of Defence, placed a high priority on creating a unified military out of the separate armies of the union's four provinces (the British Cape Colonial Forces, and the forces of the Natal Colony, the Transvaal, and the Orange River Colony). The Defence Act (No. 13) of 1912 established a Union Defence Force (UDF) that included a Permanent Force (or standing army) of career soldiers, an Active Citizen Force of temporary conscripts and volunteers as well as a Cadet organisation.[3] The 1912 law also obligated all white males between seventeen and sixty years of age to serve in the military, but this was not strictly enforced as there were a large number of volunteers. Instead, half of the white males aged from 17 to 25 were drafted by lots into the ACF. For training purposes, the Union was divided into 15 military districts.[4]: 2

Initially, the Permanent Force consisted of five regiments of the South African Mounted Riflemen (SAMR), each with a battery of artillery attached. Dorning says that '..the SAMR was in reality a military constabulary similar to the Cape Mounted Riflemen, tasked primarily with police work in their respective geographical areas.'[4]: 3 In 1913 and 1914, the new 23,400-member Citizen Force was called on to suppress several industrial strikes on the Witwatersrand.

In accordance with the 1912 Defence Act, the Active Citizen Force was established under Brig. Gen. C.F. Beyers on 1 July 1913.[5] The authorised strength of the ACF and Coast Garrison Force was 25,155 and by 31 December actual strength stood at 23,462.

First World War

Following the British declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914, South Africa was an extension of the British war effort due to her status as a Dominion within the Empire. Although self-governing, South Africa, along with other Dominions such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand, were only semi-independent from Britain.[6]

General Louis Botha, the then prime minister, faced widespread Afrikaner opposition to fighting alongside Great Britain so soon after the Second Boer War, and had to quell a militarily rebellion by some of the more extremist elements before he could send an expeditionary force of some 67,000 troops to invade German South West Africa (now Namibia). The German troops stationed there eventually surrendered to the South African forces in July 1915. In 1920 South Africa received a League of Nations mandate to govern the former German colony and to prepare it for independence within a few years, however South African occupation continued, illegally, until 1990.[7]

Later, the South African Infantry Brigade, and various other supporting units such as the South African Native Labour Corps, were deployed to France in order to fight on the Western Front as the South African Overseas Expeditionary Force under British command. The 1st South African Brigade consisted of four infantry battalion sized regiments, representing men from all four provinces of the Union of South Africa, as well as Rhodesia. The 1st Regiment was from the Cape Province, the 2nd Regiment was from Natal and the Orange Free State and the 3rd Regiment was from Transvaal and Rhodesia. The 4th Regiment was called the South African Scottish and was raised from members of the Transvaal Scottish and the Cape Town Highlanders; they wore the Atholl Murray tartan. Supporting units included five batteries of heavy artillery, a field ambulance unit, a Royal Engineers signals company and a military hospital.[8]

The most costly action that the South African forces on the Western Front fought in was the Battle of Delville Wood in 1916 – of the 3,000 men from the brigade who entered the wood, only 768 emerged unscathed.[9] Another tragic loss of life for the South African forces during the war was the Mendi sinking on 21 February 1917, when the troopship Mendi – while transporting 607 members of the South African Native Labour Corps from Britain to France – was struck and cut almost in half by another ship.[10]

In addition, the war against the German and Askari forces in German East Africa also involved more than 20,000 South African troops; they fought under General Jan Smuts's command when he directed the British campaign against there in 1915. (During the war, the army was led by General Smuts, who had re-joined the army from his position as Minister of Defence on the outbreak of the war.)[11]

Coloured South Africans also saw notable action with the Cape Corps in Palestine.

With a population of roughly 6 million, between 1914 - 1918, over 250,000 South Africans of all races voluntarily served their country. Thousands more served in the British Army directly, with over 3,000 joining the British Royal Flying Corps and over 100 volunteering for the Royal Navy. More than 146,000 whites, 83,000 black Africans and 2,500 Coloureds and Asians also served in either German South-West Africa, East Africa, the Middle East, or on the Western Front in Europe. Suffering roughly 19,000 casualties, over 7,000 South Africans were killed, and nearly 12,000 were wounded during the course of the war.[12] Eight South Africans won the Victoria Cross for gallantry, the Empire’s highest and prestigious military medal. The Battle of Delville Wood and the sinking of the SS Mendi being the greatest single incidents of loss of life.

Interwar period

Wartime casualties and post-war demobilisation weakened the UDF. New legislation in 1922 re-established conscription for white males[13] over the age of 21 for four years of military training and service and re-constituted the Permanent Force. UDF troops assumed internal security tasks in South Africa and quelled several revolts against South African domination in South-West Africa. South Africans suffered high casualties, especially in 1922, when an independent group of Khoikhoi – known as the Bondelswarts-Herero for the black bands that they wore into battle – led one of numerous revolts; in 1925, when a mixed-race population – the Basters – demanded cultural autonomy and political independence; and in 1932, when the Ovambo (Ambo) population along the border with Angola demanded an end to South African domination. During the Rand strike of 1922, 14,000 members of the ACF and certain A class reservists were called up.[14]

Expenditure cuts saw the UDF as a whole reduced. The last remaining regiment of the South Africa Mounted Riflemen was disbanded on 31 March 1926 and the number of military districts was reduced from 16 to six on 1 April 1926. The Brigade HQ of the SA Field Artillery was also disbanded.[14] In 1933 the six military districts were redesignated Commands.[4]: 9 As a result of its conscription policies, the UDF increased its active-duty forces to 56,000 by the late 1930s; 100,000 men also belonged to the National Riflemen's Reserve, which provided weapons training and practice.

Second World War

During World War II, the South African Army fought in the East African, North African and Italian campaigns. In 1939, the army at home in South Africa was divided between a number of regional commands.[15] These included Cape Command (with its headquarters at the Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town), Orange Free State Command, Natal Command, Witwatersrand Command (5th and 9th Brigades plus the Transvaal Horse Artillery), Robert's Heights and Transvaal Command (HQ Robert's Heights) and Eastern Province Command at East London.

With the declaration of war in September 1939, the South African Army numbered only 5,353 regulars,[16] with an additional 14,631 men of the Active Citizen Force (ACF) which gave peace time training to volunteers and in time of war would form the main body of the army. Pre-war plans did not anticipate that the army would fight outside southern Africa and it was trained and equipped only for bush warfare.

One of the problems to continuously face South Africa during the war was the shortage of available men. Due to its racial policies it would only consider arming men of European descent which limited the available pool of men aged between 20 and 40 to around 320,000. In addition the declaration of war on Germany had the support of only a narrow majority in the South African parliament and was far from universally popular. Indeed, there was a significant minority actively opposed to the war and under these conditions conscription was never an option. The expansion of the army and its deployment overseas depended entirely on volunteers.

The 1st South African Infantry Division took part in several actions in East Africa in 1940, North Africa in 1941 and 1942, including the Second Battle of El Alamein, before being withdrawn to South Africa.

The 2nd South African Infantry Division also took part in a number of actions in North Africa during 1942, but on 21 June 1942 two complete infantry brigades of the division as well as most of the supporting units were captured at the fall of Tobruk.

The 3rd South African Infantry Division never took an active part in any battles but instead organised and trained the South African home defence forces, performed garrison duties and supplied replacements for the South African 1st Infantry Division and the South African 2nd Infantry Division. However, one of this division's constituent brigades – 7th South African Infantry Battalion in Phalaborwa – did take part in the invasion of Madagascar in 1942.

The 6th South African Armoured Division fought in numerous actions in Italy from 1944 to 1945.

Of the 334,000 men volunteered for full time service in the South African Army during the war (including some 211,000 whites, 77,000 blacks and 46,000 Cape Coloureds and Asians), about 9,000 were killed in action, though the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has records of 11,023 known South African war dead during World War II.[17]

Post-war period

Wartime expansion was again followed by rapid demobilisation after World War II. By then, a century of Anglo-Boer clashes followed by decades of growing British influence in South Africa had fuelled Afrikaner resentment. Resurgent Afrikaner nationalism was an important factor in the growth of the National Party (NP) as the 1948 elections approached. After the narrow election victory by the NP in 1948, the government began the steady Afrikanerisation of the military; it expanded military service obligations and enforced conscription laws more strictly. Most UDF conscripts underwent three months of Citizen Force training in their first year of service, and an additional three weeks of training each year for four years after that.

In 1948, the new Minister of Defence, Frans Erasmus, aimed ' to level the playing-fields' within the Union Defence Force, which was strongly British-oriented in usages, structures, uniforms and nomenclature.[18] This developed from an attempt at affirmative action into a 'politically tinged purge'.

The various Commando units, previously 'Skietverenigings', were later classified as Type A, B or C independent Commandos and continued as single-battalion or small independent units. As part of the post-war reorganisation, the Defence Rifle Associations were disbanded in 1948 and replaced by a new Commando organisation with a strength of 90,000 men.[19] At the same time, the Afrikaans-oriented single-battalion regiments founded in 1934 underwent at least one change of name and sometimes more. An early victim was the renowned Middellandse Regiment, which became Regiment Gideon Scheepers in 1954.

It was also decided to establish and maintain two complete army divisions in the UDF: namely 1 SA Infantry Division and 6 SA Armoured Division, consisting of 1, 2, 3, 12, and 13 (CF) Infantry Brigades and the (PF) 11th Armoured Brigade. The divisions were formally established with effect from 1 July 1948, but with the exception of 11 Brigade they were disbanded on 1 November 1949, mainly as a result of difficulties in obtaining volunteer recruits to man the Citizen Force brigades. The 11th Armoured Brigade was itself disbanded on 1 October 1953. In the early 1950s the Union undertook, however, to provide one armoured division for active service in the Middle East in the event of war in the region. To this end some 200 Centurion tanks were ordered, and the first were delivered in July 1952. During Exercise Oranje, conducted in 1956, the Army trialled its Centurions for the first time in a simulated nuclear war situation.

The Defence Act (No. 44) of 1957 renamed the UDF the South African Defence Force (SADF) and established within it some quick-reaction units, or Commandos, to respond to localised threats. The SADF, numbering about 20,000 in 1958, would grow to almost 80,000 in the next two decades.

In 1960 there was another wave of regimental name-changing.[18] Regiment Gideon Scheepers became Regiment Groot Karoo, and three regiments named after famous Boer generals Regiment De La Rey (given its 13 World War 2 battle honours, the most celebrated of the 1934 battalions), Regiment Louw Wepener and Regiment De Wet were inexplicably renamed Regiment Wes-Transvaal, Regiment Oos-Vrystaat and Regiment Noord-Vrystaat. After strenuous efforts, Regiment Wes-Transvaal, Regiment Oos-Vrystaat and Regiment Noord-Vrystaat regained their honoured names.

Following the declaration of the Republic of South Africa in 1961, the "Royal" title was dropped from the names of army regiments like the Natal Carbineers and the Durban Light Infantry, and the Crown removed from regimental badges.

"Border War" (1966–1989)

In the early 1960s, the military threat by the South-West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) and its Communist backers in South West Africa prompted the South African government to increase military service obligations and to extend periods of active duty. The Defence Act (No. 12) of 1961 authorised the minister of defence to deploy Citizen Force troops and Commandos for "riot" control, often to quell anti-apartheid demonstrations, especially when it deteriorated into mob riots with loss of life. The Defence Act (No. 85) of 1967 also expanded military obligations, requiring white male citizens to perform national service, including an initial period of training, a period of active duty, and several years in reserve status, subject to immediate call-up.

From 1966 to 1989 the SADF, with its South West African Territorial Force auxiliary, fought the counter-insurgency South African Border War against SWAPO rebels in South-West Africa (Namibia). These operations included the raising of special units such as the South African 32 Battalion. They also carried out operations in support of UNITA rebels in Angola and against the Cuban troops that supported the Angolan government.

As far as conventional formations were concerned, 7 SA Division and 17, 18 and 19 Brigades were established on 1 April 1965.[4] Difficulties with manning levels saw the disestablishment of 7 SA Division on 1 November 1967 and its replacement by the Army Task Force (HQ) and 16 Brigade.

Also during the 1970s, the SADF began accepting "non-whites" and women into the military as career soldiers, not only as temporary volunteers or reservists; however, the former served mostly, if not exclusively, in segregated units while the latter were not assigned to combat roles. By the end of the 1970s, the South African military was increasingly called upon to confront external threats and internal unrest which started escalating to armed confrontation between the South African state and the liberation forces. Principal among these armed groups was that of the ANC's Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the AZAPO's Azanian People's Liberation Army and the PAC's Poqo.

In 1973 two new infantry units were established: 7 South African Infantry Battalion (Bourke's Luck) and 8 SA Infantry Battalion (Upington), as well as 11 Commando (Kimberley), which to a great extent took over the functions of the Danie Theron Combat School's training wing. In 1973 the SADF also took over responsibility for the defence of South West Africa (today Namibia) from the South African Police. During the succeeding months the Army became involved in combat operations for the first time since the Second World War, clashing with groups of SWAPO infiltrating into South West Africa.

7th and 8th Divisions, early 1980s[20]

- 7 SA Division (HQ Johannesburg)

- 71 Motorised Brigade (Cape Town)

- Cape Town Highlanders

- Cape Town Rifles

- Western Province Regiment

- 72 Motorised Brigade (Johannesburg)

- Johannesburg Regiment

- 1 Transvaal Scottish

- 2 Transvaal Scottish

- 73 Motorised Brigade (once at Kensington?)

- Rand Light Infantry

- Regiment Louw Wepner (Ladybrand?)

- Kimberley Regiment (Kimberley)

- Division Troops

- Light Horse Regiment (Johannesburg)

- Cape Field Artillery

- 7th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

- 14th Field Artillery (Potchefstroom)

- 8 SA Armoured Division (Durban)

- 81 Armoured Brigade (Pretoria)

- Pretoria Regiment (armoured) (Pretoria)

- Pretoria Highlanders

- Regiment Boland

- 82 Mechanized Brigade (Potchefstroom)

- 1 Regiment de la Rey

- Regiment de Wet

- Witwatersrand Regiment (Germiston)

- 84 Motorised Brigade (Durban)

- 1 Durban Light Infantry (Durban)

- 2 Durban Light Infantry

- Prince Alfred's Guard

- Division Troops

John Keegan, World Armies, p.639

From 1 September 1972 Army Task Force Headquarters was redesignated HQ 7 South African Infantry Division.[4] Two years later, it was decided to organise the Army's conventional force into two divisions under a corps headquarters. Both were primarily reserve (Citizen Force) formations, though the division and brigade HQs were Permanent Force. The headquarters of the two divisions were established on 1 August 1974, and 8th Armoured Division was active at its headquarters at Lord's Grounds, Durban, until at least 27 September 1992.[21] 1 SA Corps itself was established in August 1974 and was active until 30 January 1977.[22] It appears from Colonel Lionel Crook's book on 71 Brigade[23] that four of the six brigades were redesignations of 16, 17, 18, and 19 Brigades. 71 Motorised Brigade was the former 17 Brigade, 72 Brigade was the former 18 Brigade, 73 Brigade was a new formation, 81 Brigade was the former 16 Brigade, 82 Brigade was the former 19 Brigade, and 84 Brigade was new.[23]: 2

In the early 1980s, the Army was restructured in order to counter all forms of insurgency while at the same time maintaining a credible conventional force. To meet these requirements, the Army was subdivided into conventional and counterinsurgency forces. The counterinsurgency forces were further divided into nine territorial commands, each of which was responsible to the Chief of the Army. This force consisted of members of the Permanent Force, Commandos, and a few selected Citizen Force units. The Citizen Force, through the 7 and 8 Divisions, provided the conventional defence force. By July 1987 the number of territorial commands was expanded to ten, and the Walvis Bay military area was often counted as an eleventh.[24] The commands were the Western Province Command (HQ Cape Town, 1959-1998); Eastern Province Command (HQ Port Elizabeth, 1959-1998); Northern Cape Command (HQ Kimberley); Orange Free State Command (HQ Bloemfontein, 1959-1998); Northern Transvaal Command (HQ Pretoria); Witwatersrand Command (HQ Johannesburg, subject of a bombing in 1987);[25] Northwestern Command (HQ Potchefstroom); Eastern Transvaal Command (HQ Nelspruit); Natal Command (Durban), and Far North Command (HQ Pietersburg, which in late 1993 and early 1994 included Regiment Hillcrest which was then part of 73 Motorised Brigade, and 73 Brigade itself). The part-time force also operated in the military area of Walvis Bay.

During this same period, the Engineers and Signals were grouped into the first of the 'type' formations, the South African Army Engineer Formation (in 1982) and the South African Army Signals Formation (in 1984). Both these formations were made directly responsible to Chief of Army.

In 1984 Northern Transvaal Command was subdivided and Eastern Transvaal Command (Nelspruit) and Far North Command (Pietersburg) formed. The two new Commands were regarded as theatres and as such also had responsibility for conventional operations (and units) within their areas.[26] For example, Far North Command had 73 Motorised Brigade within its area. Southern Cape Command may have been disbanded, and Northern Cape Command established, in 1986.[27] In 1989 the RLI became the conventional reserve for Far North Command. The area of responsibility of each commands followed the boundaries of the Economic Development Regions.[28] Before the dissolution of the territorial commands General Derrick Mgwebi is also reported to have headed Mpumalanga Command.

During the 1980s, the legal requirements for national service were to register for service at age sixteen and to report for duty when called up, which usually occurred at some time after a man's eighteenth birthday or on leaving school.[3] National service obligations could be fulfilled by active-duty military service for two years and by serving in the reserves, generally for ten or twelve years. Reservists generally underwent fifty days per year of active duty or training, after their initial period of service. The system was for the most part that the National Service requirement was for 720 days (two years) and subsequent reserve duty was a further 720 days. The reserve duty was broken up depending on the needs of the units and of the individual concerned. This generally worked out as a ninety-day "operational" commitment one year, followed the next year by a thirty-day commitment in addition to any courses, parades or admin evenings that might be required. Members of the Reserve were able to volunteer for further duty in addition to that mandated. This additional, voluntary, service was recognised with the award of the Emblem for Voluntary Service (EVS) (now the Badge for Reserve Voluntary Service (BRVS)) for five years of voluntary service over and above the mandated commitment. The requirements for national service changed several times during the 1980s and the early 1990s in response to national security needs, and they were suspended in 1993.

Post-1994

From the early 1990s (after 1992) to 1 April 1997, the SA Army maintained three 'small' divisions, the 7th (HQ Johannesburg), 8th (HQ Durban) and 9th (HQ Cape Town).[29] They consisted of a reconnaissance battalion, two anti-aircraft defence battalions (AA guns), two battalions of artillery (G-5s and G-6s), a battalion of 127 mm MRLs, an engineer battalion, two battalions of Olifant MBTs, two battalions mounted in Ratel ICVs, and finally two battalions mounted in Buffel APCs. They were all amalgamated into the 7th South African Division on 1 April 1997, and became the 73rd, 74th and 75th Brigades respectively.[30]

On 1 April 1997 Regiment Louw Wepener (Bethlehem), Regiment De Wet (Kroonstad) and Regiment Dan Pienaar (Bloemfontein) were absorbed into Regiment Bloemspruit.

7th Division was disbanded on 1 April 1999 and all army battalions were assigned to 'type' formations, in accordance with the recommendations of the South African Defence Review 1998.[31] The 'type' formation force structure was implemented in accordance with the recommendations of auditing firm Deloitte and Touche, who were contracted to draw up a plan to make the SA Army more economically efficient. The Deloitte and Touche plan had the army separate its combat forces into 'silo' style formations for armour, infantry, artillery, and engineers. Deane-Peter Baker of the South African Institute for Security Studies said that the D&T plan, while alleviating, to an extent, the mistrust of the new South African leadership of the remaining apartheid-era South African Defence Force personnel in middle management positions, reduced the combat effectiveness of the Army, and was seen by 2011 as a mistake.[32] Another mistaken decision was the decision to limit the force design of the SANDF to rely on short logistic lines for highly mechanised mobile forces in defence of national territory, as it causes many supply issues during modern foreign deployments. This is one of the major problems of the army and various solutions are being considered by the government to better equip forces deployed in out-of-area force projection operations.[33]

Though non-white personnel did serve as unarmed labourers with the army in both World Wars, a number of non-whites were employed in segregated units during the Border War, and a number of units were completely desegregated, it was not until 1994 – when South Africa achieved full democracy – that the army as a whole was made open to all races. Today the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has racial quotas to make sure that White, Black, Coloured, and Indian South Africans are proportionately represented in the armed forces.[34]

During 2006 the Army released its ARMY VISION 2020 guidelines document, in a fresh attempt to reassess the 1998 structures which had proved wanting. The army planned a return to a division based structure, from the previous structure where units are simply provided as needed to the two active brigades. In many respects the plan was an attempt to undo the effects of the Deloitte and Touche-inspired force design that came into effect in 2001.[32] The new plan was to create two divisions and a special operations brigade to conduct mountain, jungle, airborne and amphibious operations. Specialised training would have had to be carried out, as and when funds become available. A works regiment was also to have been created, to help with the maintenance of army and Defence Force buildings and infrastructure. However the plan was not implemented, and appeared to stall until the issue of the 2014 South African Defence Review. With the release of that review in mid-2014 it appears possible that the 2006 planning may be reinvigorated.

Concerns have been raised as to the operational capabilities of the army given the high proportion of the army's budget spent on salaries (around 80%) and low amounts budgeted for capital (5%) and operational (15%) capacity.[35] In addition to the large ratio of officers to soldiers, critical skills shortages, high average age of service personnel (48 years), and low proportion that are medically fit enough to be readily deployable (about 10% of personnel).[35]

Peacekeeping and other operations

The post-1994 South African Army has been extensively involved in peacekeeping operations under United Nations and African Union command in other African countries such as the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), the United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB) and the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), and is doing well with these challenges, despite some pitfalls and budget cuts.

Other operations that the Army was tasked with by government include: Operation Boleas (Lesotho), Operation Fibre (Burundi), Operation Triton (five times in the Comoros), Operation Amphibian (Rwanda), Operation Montego (Liberia), Operation Espresso (Ethiopia) , Operation Cordite (Sudan), Operation Teutonic and Operation Bulisa (both in the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Operation Pristine (Ivory Coast), Operation Vimbezela (Central African Republic) and Operation Bongane (Uganda).[36]

The most notable UN deployments since 1994 have been Operation Vimbezela (Central African Republic) and Operation Mistral, the South African contribution to the United Nations mission to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Central African deployment developed rapidly into a combat mission and led to the loss of 15 soldiers from 1 Parachute Battalion in Bangui. The contribution to Ops Mistral, while starting in 2009, became a completely different tasking with the contingent sent in 2013 to the United Nations Force Intervention Brigade, a ~3000-strong intervention brigade that was authorised by the United Nations Security Council on 28 March 2013 through United Nations Security Council Resolution 2098. It is the first United Nations peacekeeping unit that has been specifically tasked to carry out offensive operations against armed rebel groups operating in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, specifically those that threaten the State authority and civilian security. They can also carry out their mandate without the help of the Congolese Army. The brigade is made up of troops from Tanzania, South Africa and Malawi and has had several successes against rebel groups such as M23 militia.[36][37]

All Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, including South Africa, are working on establishing the SADC Standby Brigade as an element of the African Standby Force. Working towards the creation and strengthening of these regional brigades should contribute to the peace and security of the region.[33] The major challenges that the Army face today is to readdress its current force design, to balance its budget, to integrate new equipment to replace several ageing systems, and to prepare forces for the African Standby Force and African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises.[33]

Structure

Since the Defence Act of 1912, the South African Army has been comprised, in general terms, of three groupings. The first is the standing army, also known since the 1970s as the Permanent Force. A military reserve force was also established by the terms of the 1912 Act and initially designated the Active Citizen Force. The force was established on 1 July 1913.[14] Other designations through the years have included Active Reserve Force, Citizen Force, Conventional Reserve and Territorial Reserve. The Deloitte and Touche plan, as well as various policies over the years have referred to a 'One Force Concept' where reservists and reserve units are supposed to be treated on an equal footing with the permanent force counterparts. This is often not the case.

Due to the restructuring of the Reserves, the exact number of reserves is difficult to ascertain. However the 2011/12 planning target was 12,400 reserves.[38]

The third grouping was initially the Defence Rifle Associations, which later became the Commandos, a rural self-defence force. There were several thousand other members in the Commandos. Each Commando was responsible for the safeguarding and protection of a specific community (both rural or urban). However, this system was phased out between 2003 and 2008 "because of the role it played in the apartheid era", according to the Minister of Safety and Security Charles Nqakula.[39] The last commando unit, that at Harrismith in the Free State, was disbanded in March 2008.

South African military ranks are derived from that of the British Armed Forces, with Army ranks derived from the British Army.

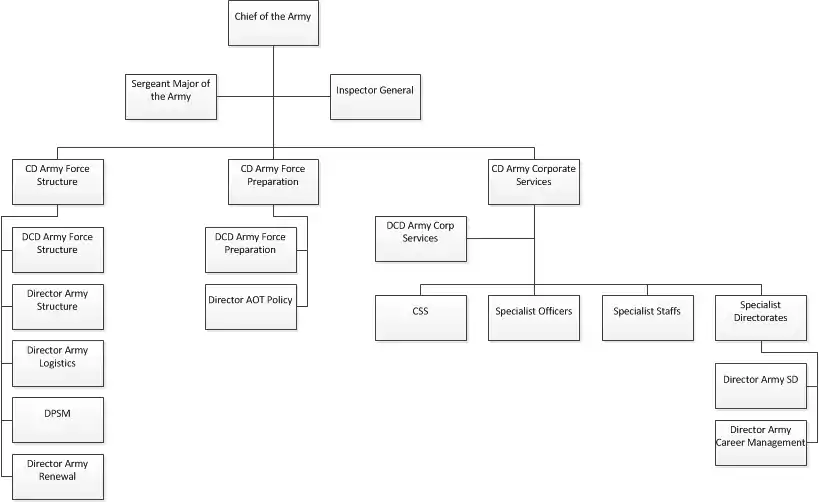

The SA Army command structure is as follows:[40]

Directorates

- Chief of the SA Army Force Structure - To structure the SA Army in order to provide the SA Army component of the Landward Defence Capability.[41]

- Chief of the SA Army Force Preparation - Responsible for directing, orchestrating and controlling the combat readiness of SA Army Forces

- Chief of the SA Army Corporate Services - Directing corporate resources, services and advice directed towards operationalising the SA Army strategy.

- Inspector General - Provides an internal audit service within the Army strategy.

- Chief of the SA Army Reserves - To give specialist advice to Chief of the SA Army and his staff in all Reserves related issues

- Sergeant Major of the Army - To enhance discipline in the SA Army and enforce standards of discipline.

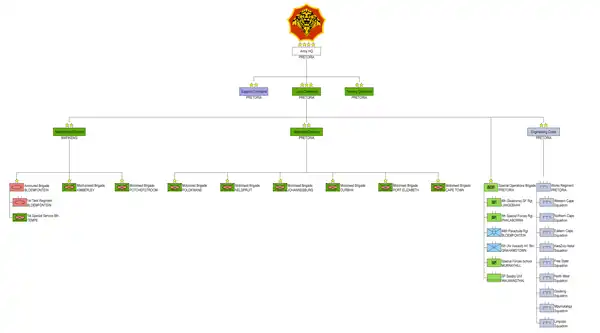

Formations and units

The two standing army brigades are Headquarters 43 South African Brigade and Headquarters 46 South African Brigade.[40] Each of these two headquarters are organised to provide four headquarters groups. Two of these units should be available for deployment at any one time whilst the other two are on leave and in training.

In accordance with the Deloitte and Touche structure plan, the army was reorganised into single-branch 'formations':

- South African Armoured Corps

- South African Army Infantry Formation

- South African Army Artillery Formation

- South African Army Air Defence Artillery Formation

- South African Army Engineer Formation

- South African Army Signal Formation

- South African Army Support Formation

- South African Army Training Formation

Existing and former administrative corps and branches of the South African Army can be seen at South African Army corps and branches.

Many Army units are routinely placed under the nine joint operational-tactical headquarters that the SANDF Chief of Joint Operations supervises directly through Joint Operations Division (IISS 2013). Brigadier-General McGill Alexander took over as General Officer Commanding RJTF South in 2002, but in 2003 he was tasked to close down all the RJTFs.

The South African Army is changing structure into "4 Modern Brigades". The first of which - The Mechanized brigade has already been established at Lohatlha in the Northern Cape.

Bases

The South African Army maintains large bases in all 9 provinces of the country, mostly in or around major cities and towns:[42][43][44][45][46] The army has 10 general support bases, seemingly part of the South African Army Support Formation.

Eastern Cape

- The Grahamstown army base houses the 6 South African Infantry Battalion (Air Assault) and the Chief Makhanda Regiment (Air Assault).

- Port Elizabeth is home to Chief Maqoma Regiment (Air Assault).

- The Mthatha army base is home to the 14 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

- Port Elizabeth is home to the Nelson Mandela Regiment (Light Infantry).

- East London is home to the Buffalo Volunteer Rifles (Light Infantry).

Free State

- One of the largest bases in the country[47] is Tempe Military Base which is located in Bloemfontein and is home to 1 South African Tank Regiment, 1 Special Service Battalion (Armoured Car Regiment), the South African School of Armour (which offers decentralized training to regular and reserve regiments), 44 Parachute Regiment and 1 South African Infantry Battalion (Mechanized Infantry). The parachute training wing is also located here. Bloemfontein is also home to the Mangaung Regiment (Light Infantry), General Dan Pienaar Artillery Regiment (Artillery) and Thaba Bosiu Armoured Regiment (Tank Regiment) as well as 3 Military Hospital.

- Kroonstad is home to the School of Engineers, and an Army Band.

- Bethlehem is home to 2 Field Engineer Regiment SAEC.[48][49]

Gauteng

- Army headquarters is located at Dequar Road, Pretoria, which also houses the State Artillery Regiment (Artillery) and the Pretoria Armoured Regiment (Tank Regiment).

- Pretoria is home to a large joint services base called Thaba Tshwane, which is also home to the South African Army College, the National Ceremonial Guard and Band, the Military Police School, 1 Military Hospital, Madzhakandila Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery), Tshwane Regiment (Motorised Infantry), and Steve Biko Artillery Regiment (airborne mortars). Just south of Thaba Tshwane and within a separate area is Technical Base Complex Centurion, which is home to Bagaka Regiment, Ukhosi Parachute Engineer Regiment, 1 Military Printing Regiment, 4 Survey and Map Regiment, and the Army Engineer Formation.[50] Reportedly it also houses the Technical Service Training Centre, and units from the SAMHS and the SAAF. The base, whose TEK appellation may be derived from "Tegnies Basis Werkswinkel", is located at Centurion, south of Pretoria. It has a housing complex for active members.

- Wallmannsthal is home to 43 SA Brigade Headquarters.

- Centurion is home to 3 Parachute Battalion.

- The Joint Support Base in Wonderboom houses the School of Signals, 1 Signal Regiment, 2 Signal Regiment, 3 Electronic Workshop, 4 Signal Regiment and 5 Signal Regiment.

- Several army bases in Johannesburg house 21 South African Infantry Battalion, 46 South African Brigade headquarters, 6th Field Engineers Regiment, 1 Construction Regiment, 35th Engineering Supply Regiment, the Rand Light Infantry (Motorised Infantry), The Johannesburg Regiment (Motorised Infantry), the Solomon Mahlangu Regiment (Motorised Infantry), OR Tambo Regiment (Motorised Infantry), the Andrew Mlangeni Regiment (Motorised Infantry), Lenong Regiment (Motorised Infantry), the Sandfontein Artillery Regiment (Artillery) and the Johannesburg Light Horse Regiment (Armoured Car Regiment).

- Benoni is home to IWombe Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery).

- Springs is home to Sekhukhune Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery).

- The Heidelberg Army Base is home to the SA Army Gymnasium.

- Germiston is home to the Bambatha Rifles (Mechanized Infantry).

- Vereeniging is home to Galeshewe Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery).

Western Cape

- Several army bases are located in Cape Town and are home to the 9th South African Infantry Battalion (Seaborne Infantry), The Army Band, the Gonnema Regiment (Mechanized Infantry), General Jan Smuts Regiment (Mechanized Infantry), the Chief Langalibalele Rifles (Motorised Infantry), Nelson Mandela Artillery Regiment (Artillery), Autshumato Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery), Blaauwberg Armoured Regiment (Armoured Car Regiment) and Ihawu Field Engineer Regiment.[51]

- The Oudtshoorn army base houses the South African Infantry School.

Northern Cape

- An Army base in Kimberley is home to the Air Defence Artillery School, 10 Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery), 3 South African Infantry Battalion (the basic training unit for the Army), the Kimberley Regiment (Motorised Infantry) and Madzhakandila Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Air Defence Artillery).

- The Lohatla training area is home to the SA Army Combat Training Centre where large army field exercises take place. It also houses 101 Field Workshop and 16 Maintenance Unit.

- An Army base in Upington is home to 8 South African Infantry Battalion (Mechanized Infantry).

North-West

- The Potchefstroom army base is home to the School of Artillery, 4 Artillery Regiment (Artillery), Artillery Mobile Regiment (Artillery), the School of Tactical Intelligence, 1 Tactical Intelligence Regiment, General de la Rey Regiment (Mechanized Infantry), Regiment Potchefstroom Universiteit (Artillery) and Molapo Armoured Regiment (Armoured Car Regiment).

- The Mahikeng Army base is home to 10 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

- Orkney is home to Regiment Skoonspruit (Motorised Infantry).

- The Zeerust Army Base is home to 2 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).[52]

KwaZulu-Natal

- Durban is home to an Army Band, the Durban Light Infantry (Mechanized Infantry), King Cetshwayo Artillery Regiment (Artillery), Queen Nandi Mounted Rifles (Tank Regiment), Umvoti Mounted Rifles (Armoured Car Regiment), the King Shaka Regiment (Motorised Infantry) and the 19 Field Engineer Regiment SAEC.

- Pietermaritzburg is home to the Ingobamakhosi Carbineers (Motorised Infantry).

- The Mtubatuba army base is home to 121 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

- The Ladysmith army base is home to 5 South African Infantry Battalion.[53]

Mpumalanga

- Middelburg Army base is home to 4 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

- Barberton is home to General Botha Regiment (Motorised Infantry).

Limpopo

- The Polokwane army base is home to an Army Band and Mapungubwe Regiment (Motorised Infantry).

- The Phalaborwa army base is home to 7 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

- The Thohoyandou army base is home to 15 South African Infantry Battalion (Motorised Infantry).

The main South African Army Headquarters are located in Salvokop, Pretoria in the Dequar Road Complex along with 102 Field Workshop SAOSC, 17 Maintenance Unit and the South African Military Health Service Military Health Department.

Budget

A budget of approximately R15.7 billion was allocated for fiscal year 2023.

The vast majority of army equipment is nearing the end of its service life, with some items (like the Olifant main battle tank) dating from decades ago.

The South African National Defence Force has however started to remedy the situation with the procurement of 244 Badger infantry fighting vehicles under the Hoefyster programme. Other procurements are planned and should follow in line with the guideline document – Army Vision 2020. The SANDF has launched a project called "African Warrior" which is aimed in modernising the equipment and weapons of the SANDF. The project has been very successful in recent years and the South African Army has now put in service a 21st-century R4 assault rifle.[54]

Equipment

The South African Army maintains a wide variety of military equipment.

Equipment summary

| Type | Name | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Main battle tanks | Olifant | 195[55] |

| Tank destroyers | Rooikat | 240[56] |

| Ratel ZT-3 | 52[57] | |

| Infantry fighting vehicles | Ratel IFV | 1,200[58] |

| Badger IFV | 244 on order[59] | |

| Armoured personnel carriers | Mamba | 440+[60] |

| Mine-resistant ambush-protected | Casspir | 370+[61] |

| Towed artillery | GV5 Leopard | 72[62] |

| GV1 25-pounder | N/A[63] | |

| Self-propelled artillery | GV6 Rhino | 43[64] |

| T5-52 | 6[65] | |

| Rocket artillery | Bateleur FV2 | 25[66] |

| Valkiri | 76[67] | |

| Anti-aircraft autocannon | Oerlikon GDF | 150[68] |

| ZU-23-2 Zumlac | 36[69] | |

| Armoured military trucks | SAMIL 20 | Thousands[70] |

| SAMIL 50 | Thousands[71] | |

| SAMIL 100 | Thousands[72] | |

| MAN Transport Trucks | N/A[73] | |

| Kynos Aljaba Trucks | N/A[74] |

Future programmes

Source[75]

- Project Aorta: A scheme for a new main battle tank. The South African Armoured Corps operated up to a 168 Olifant Mk1B and Mk2 MBT, modified Centurion cruiser tanks. The Centurion tank in its early versions first saw action in Germany in the closing weeks of the Second World War (three were rushed to Northern Germany but failed to arrive in time to see action). Between 90 and 110 MBT were to have formed part of the government's ongoing Strategic Defence Package but fell by the wayside for a variety of reasons.

- Project Hoefyster: Partial acquisition of a new generation infantry fighting vehicle. 244 Badger Infantry Combat Vehicles on order at a cost of R8.4 billion. Denel Land Systems awarded contract.

- Project Musuku: Development and partial acquisition of an advanced multi-role light artillery gun capability in the form of the 105 mm "Light Experimental Ordnance".

- Project Outcome (GBADS III): Planned acquisition of the Umkhonto all weather surface-to-air-missile (AWSAM). No dates as yet.

- Project Protector (GBADS II): Development and partial acquisition of a mobile ground-based air defence system. Possible R3bn budget for land-based Umkhonto IR missile.

- Project Sepula: A new generation armoured personnel carrier for the SA Army to replace the 440+ Mamba and 370+ Casspir that remain in service. The thinking is the Sepula vehicle should have a high level of commonality with the Vistula choice and at least share the drive train to form a "family" of vehicles. Assuming about 90 vehicles a motorised infantry battalion and multiplying that with the number of regular units as well as "some" Reserve Force regiments, about 1000 will be required at a cost of about R3 to R4 million each.

- Project Tladi: "Zone 1" anti-tank. New generation portable infantry A/T rocket launcher to replace RPG7 and FT5.

- Project Vistula: A drive to acquire up to 3000 new tactical 5t and 10t trucks for the SA Army and its sister Services. To replace the SAMIL series.

- Project Warrior: Dismounted soldier system. Acquisition study for low risk items completed 2006. Development plan for complex sub-systems underway.

Gallery

Notes

- From the law creating the Union Defence Force.

References

- "SANDF not meeting staffing targets". defenceweb.co.za. DefenceWeb. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "A Country Study: South Africa". The Library of Congress. 1996. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Early Development of the South African Military". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1996. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Dorning, W.A. (28 February 2012). "A concise history of the South African Defence Force (1912-1987)" (Online). Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. 17 (2). doi:10.5787/17-2-420. ISSN 2224-0020. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Dorning, 3.

- Stevenson, David (2005). 1914-1918 : the history of the First World War. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-190434-4. OCLC 688607944.

- James, W. Martin. (2011). A political history of the civil war in Angola, 1974-1990. New Brunswick [N.J.]: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1506-2. OCLC 693560852.

- "South African forces in the British Army". Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "South African Military History Society - Journal - The Lessons of Delville Wood". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Africans played key, often unheralded, role in World War I". AP NEWS. 1 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Farwell, Byron (1989). The Great War in Africa, 1914-1918. New York. ISBN 0-393-30564-3. OCLC 21815763.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Great Britain. War Office (1922). Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920. Robarts - University of Toronto. London H.M. Stationery Off.

- Lillie, Ashley C. (2012). "The Origin and Development of the South African Army" (Online). Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. 12 (2). doi:10.5787/12-2-618. ISSN 2224-0020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Dorning, 8.

- Ryan, David A. "Union Defence Forces 6 September 1939". World War II Armed Forces – Orders of Battle and Organizations. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Wessels, Andre (June 2000). "The first two years of war: The development of the Union Defence Forces (UDF) September 1939 to September 1941". Military History Journal. 11 (5). Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Commonwealth War Graves Commission". cwgc.org. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Steenkamp, Willem (1996). "The Multi Battalion Regiment: A Old Concept with a New Relevance". ISS. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "A Short History of the South African Army". Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

From: South African Defence Force Review 1991

- John Keegan, World Armies, p.639, cited in Lt Cdr Carl T. Orbann USN, 'South African Defense Policy,' Thesis for the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA., June 1984.

- "SAMHS Newsletter". South African Military History Society. August 1992. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

DURBAN: 13th August. Evening outing to visit 8 Armoured Divs. H.Q. at Lords Grounds. Old Fort Road. To be conducted by Brigadier Frank Bestbier SD

- "SACMP Corps History 1946-1988". redcap. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Crook, Lionel (1994). Greenbank, Michele (ed.). 71 Motorised Brigade: a history of the headquarters 71 Motorised Brigade and of the citizen force units under its command. Brackenfell, South Africa: L. Crook in conjunction with the South African Legion. ISBN 9780620165242. OCLC 35814757.

- "SA Army/Leër". sadf.info. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.. Ten commands were listed in The SADF: A Survey: Supplement to Financial Mail, July 10, 1987, p.21

- "Grosskopf recounts 1987 Wits command bombing". iol.co.za. IOL News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- "A Short History of the South African Army". rhodesia.nl. From: South African Defence Force Review 1991. 1991. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Commands and Military Areas". The British and Commonwealth Military Badge Forum. 19 August 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Sass, Brig Bill (Rtd) (1993). "An Overview of the Changing South African Defence Force". South African Defence Review. Institute for Security Studies (13). Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- See Jane's Defence Weekly 20 December 1992 and, earlier, 20 July 1991. The term 'small' is used here in comparison with the 'normal' strength of a division of nine manoeuvre battalions. Divisional HQ location source http://www.iss.co.za/pubs/asr/SADR13/Sass.html Archived 16 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- "SACMP Corps History 1988–98". redcap. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (17 February 2010). "Fact file: 7 SA Division". defenceweb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Deane-Peter Baker, 17 October 2007: South African Army Restructuring A Critical Step Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Institute for Security Studies

- "The post-apartheid South African military: Transforming with the nation" (PDF). Institute for Security Studies Africa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- "Department of Defence Annual Report 2018/19" (PDF). Parliamentary Monitoring Group. pp. 161, 169. ISBN 978-0-621-47311-7.

- Mills, Greg (30 January 2019). "The SANDF's Real Challenge: It's become a Welfare not a Warfare Agency". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "African peacekeeping deployments show what the SANDF can do". defenceweb.co.za. DefenceWeb. 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Garcia, Antonio (2018). South Africa and United Nations Peacekeeping Offensive Operations : Conceptual Models. Baltimore, Maryland: Project Muse. ISBN 9780797496866. OCLC 1154841748.

- "Department of Defence Annual Report FY11/12" (PDF). p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- De Lange, Deon (28 May 2008). "South Africa: Commandos Were 'Hostile to New SA'". Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- "SA Army Force Structure: Level 2" (PDF). army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Structure: SA Army Structure: Level 2". Army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 February 2010). "Fact file: The SA Infantry Corps". defenceWeb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 February 2010). "Fact file: The SA Armoured Corps". defenceWeb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 February 2010). "Fact file: The SA Artillery". defenceWeb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 February 2010). "Fact file: The SA Air Defence Artillery". defenceWeb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (9 February 2010). "Fact file: The SA Tactical Intelligence Corps". defenceWeb.co.za. DefenceWeb. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Army Bases South Africa". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (17 June 2010). "Fact file: Regiment Bloemspruit". defenceWeb. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "SA Army Contact Us: Free State Province, South Africa". Army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "SA Army Contact Us: Gauteng Province, South Africa". Army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "SA Army Contact Us: Western Cape Province". army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "SA Army Contact Us: North West Province, South Africa". army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "SA Army Contact Us: KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa". army.mil.za. SA Army: RSA Dept of Defence. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Denel showcases a 21st Century R4 assault rifle at AAD". DefenceWeb. 24 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- "home". 18 April 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "home". 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "home". 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "home". 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Helfrich, Kim (15 October 2021). "Hoefyster is another Denel casualty". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "home". 8 July 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "home". 8 July 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "Denel GV5 Luiperd (G5 Leopard)". www.militaryfactory.com. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "GV1 25-pounder" (PDF). 13 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (10 February 2011). "Fact file: G6 L45 self-propelled towed gun-howitzer". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Martin, Guy (5 January 2018). "South African Army artillery deal confirmed". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (27 January 2011). "Fact file: Denel FV2 Bateleur Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS)". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (27 January 2011). "Fact file: Denel FV2 Bateleur Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS)". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Helfrich, Kim (28 March 2014). "Upgrade for South Africa's air defence system". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Martin, Guy (1 February 2013). "South African National Defence Force". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Helfrich, Kim (17 March 2022). "Cuban expertise sees over ten thousand military vehicles serviceable again". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Helfrich, Kim (17 March 2022). "Cuban expertise sees over ten thousand military vehicles serviceable again". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Helfrich, Kim (17 March 2022). "Cuban expertise sees over ten thousand military vehicles serviceable again". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (16 August 2011). "Imperial keeps SANDF MAN trucks running". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "Kynos Aljaba | Weaponsystems.net". weaponsystems.net. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (26 May 2009). "SANDF projects: past, present & future". defenceWeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

Further reading

| Library resources about South African Army |

| Library resources about South African Military History |

- Frankel, Philip (2000). Soldiers in a Storm: The Armed Forces in South Africa's Democratic Transition (paper). Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3747-0. LCCN 00032102. OL 6782707M.

- Garcia, Antonio (2018). South Africa and United Nations Peacekeeping Offensive Operations : Conceptual Models. Baltimore, Maryland: Project Muse. ISBN 9780797496866. OCLC 1154841748.

- Hamann, Hilton (23 July 2007). Days of the Generals: The Untold Story of South Africa's Apartheid-era Military Generals (1st ed.). Struik Publishers. ISBN 978-1868723409.

- Nelson, H.D. (1981). South Africa: A Country Study. U.S. Department of the Army Pamphlet. Vol. 550–93. (also possibly is a 1971 edition)

- Siegfried, Stander (1985). Like the Wind, The Story of the SA Army. Cape Town: Saayman & Weber.

- Volker, W. Victor (2010). Army signals in South Africa: the story of the South African Corps of Signals and its antecedents. Pretoria: Veritas Books.

- Volker, W. Victor (2010). Signal units of the South African Corps of Signals and related signal services. Pretoria: Veritas Books. ISBN 978-0620453455.

- Volker, W. Victor (2010). 9c - Nine Charlie!: Army Signallers in the Field: The Story of the Men and Women of the South African Corps of Signals, and Their Equipment. Pretoria: Veritas Books. ISBN 978-0620453462.

- Vrdoljak, Mary Kathleen (1970). The history of South African regiments: A select bibliography (Thesis). Cape Town: University of Cape Town Libraries.

- Wessels, André (2013). "South Africa's Land Forces, 1912-2012". Journal for Contemporary History. 38 (1): 229–254.

External links

- Official South African Army Website

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)