South Korean defectors

After the Korean War, 333 South Korean people detained in North Korea as prisoners of war chose to stay in North Korea. During subsequent decades of the Cold War, some people of South Korean origin defected to North Korea as well. They include Roy Chung, a former U.S. Army soldier who defected to North Korea through East Germany in 1979. Aside from defection, North Korea has been accused of abduction in the disappearances of some South Koreans.

Occasionally, North Koreans who have defected to South Korea have decided to return. Since South Korea does not permit its naturalized citizens to travel to the North, they have made their way back to their home country illegally, and thus became "double defectors". From a total of 25,000 North Korean defectors living in South Korea, about 800 are missing, some of whom may have returned to the North. The South Korean Ministry of Unification recognizes only 13 defections officially, as of 2014.

Background

Both sides have recognized the propaganda value of defectors, even immediately after the Division of Korea in 1945. Since then, the number of defectors has been used by both the North and the South (see North Korean defectors) to try to prove the superiority of their respective political systems (the country of destination).[1]

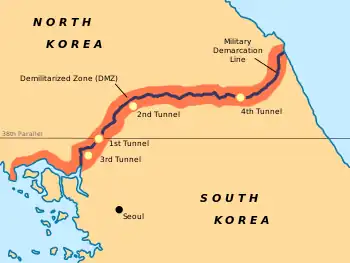

North Korean propaganda has targeted South Korean soldiers patrolling the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).[2]

Aftermath of the Korean War

A total of 357 prisoners of war detained in North Korea after the Korean War chose to stay in North Korea rather than be repatriated home to the South. These included 333 South Koreans, 23 Americans, and one Briton. Eight South Koreans and two of the Americans later changed their mind.[1] However, the exact number of prisoners of war held by North Korea and China has been disputed since 1953, due to unaccounted South Korean soldiers. Several South Koreans defected to the North during the Cold War: In 1953, Kim Sung Bai, a captain in the South Korean air force, defected to North Korea with his F51 Mustang.[3] In 1985, Ra il Ryong, a South Korean private, defected to North Korea and requested asylum.[4] In 1988, a Korean employee at a U.S. army unit in South Korea defected to North Korea. His name was Son Chang-gu, a transport officer.[5]

During the Cold War, several U.S. Army servicemen defected to North Korea. One of them, Roy Chung, was born to South Korean immigrants. Unlike the others who defected across the DMZ, he defected by first crossing the border between West and East Germany in 1979.[1] His parents accused North Korea of abducting him. The United States was not interested in investigating the case, as he was not a "security risk", and in similar cases it was usually impossible to prove that a kidnapping had occurred. There were several other cases of South Koreans mysteriously disappearing and moving to North Korea at that time, including the case of a geology teacher from Seoul who disappeared in April 1979 while he was having a holiday in Norway. Some South Koreans also accused North Korea of attempting to kidnap them while staying abroad. These alleged kidnapping attempts occurred mainly in Europe, Japan or Hong Kong.[6]

Double defectors

There are people who have defected from North Korea to South Korea, and then have defected back to North Korea again. In the first half of 2012 alone, there were 100 cases of "double defectors" like this. Possible reasons for double defectors are the safety of remaining family members left behind, North Korea's promises of forgiveness and other attempts to lure the defectors back,[7] as well as widespread discrimination faced in South Korea.[8][9] 7.2% of the North Korean defectors living in South Korea are unemployed, which is twice the national average.[10] In 2013, there were 800 North Korean defectors unaccounted for out of 25,000 people. They might have gone to China or Southeast Asian countries on their way back to North Korea.[11] South Korea's Unification Ministry officially recognizes only 13 cases of double defectors as of 2014.[12]

South Korea's laws do not allow naturalized North Koreans to return. North Korea has accused South Korea of abducting and forcibly interning those who want to and has demanded that they be allowed to leave.[13][14][15]

Contemporary South Korean-born defectors

North Korea has targeted its own defectors with propaganda in attempts to lure them back as double defectors,[7] but contemporary South Korean defectors born outside of North Korea are generally not welcome to defect to the North. In recent years there have been seven people who tried to leave South Korea, but they were detained for illegal entry in North Korea, and ultimately repatriated.[16][17][18] As of 2019, there are reportedly 5461 former South Korean citizens living in North Korea.[19]

There has also been fatalities as a result of failed defections. One defector died in a failed murder-suicide attempt by her husband while in detention.[18] One person who attempted to defect was shot and killed by South Korean military forces in September 2013.[20]

This is an incomplete list of notable cases of defections from South Korea to North Korea.

- 1986

- Choe Deok-sin, a former South Korean Foreign Minister defected with his wife, Ryu Mi-yong, to North Korea.[21]

- 1998

- 2004

- A 33 year old South Korean soldier named Chen was arrested for violating the National Security Law by secretly crossing in to North Korea and providing information about the military unit he served in. Chen made it to Hoeryong in North Hamgyŏng Province of North Korea by crossing the Tumen River running through the Jilin province of China.[23] Deported by the North as an illegal entrant and repatriated to South Korea from China, Chen was suspected of providing military information to North Korea like the location of the air force fighter wing he served in and the location of anti-air batteries.

- 2005

- A 57 year-old South Korean fisherman named Hwang Hong-ryon in the Hwangman-ho crossed the Northern Limit Line into North Korea whilst reportedly "dead drunk".[24] The South Korean navy fired some 20 warning shots from various arms, including a 60 mm mortar, but were unable to stop the ship.[25]

- 2009

- 2019

- Choe In-guk, the son of former South Korean Foreign Minister Choe Deok-sin, said he had decided to "permanently resettle" in North Korea to honour his parents' wish that he live there and devote himself to the unification of the Korean peninsula, according to North Korea’s state-controlled news website Uriminzokkiri.[27]

- 2022

- An unidentified South Korean citizen had defected to North Korea at the start of January by crossing into the Demilitarized Zone.[28]

List of notable defectors

- Choe Deok-sin, a South Korean foreign minister

- Ryu Mi-yong, the chairwoman of Chondoist Chongu Party and wife of Choe

- Kim Bong-han, a North Korean researcher of acupuncture

- Oh Kil-nam, a South Korean economist who later defected back to the South

- Shin Suk-ja, the wife of Oh Kil-nam, who was held together with their daughters as prisoners of conscience

- Ri Sung-gi, a North Korean chemist known both for his invention of vinylon, and possible involvement in nuclear weapons research

- Roy Chung (born Chung Ryeu-sup), the fifth U.S. Army defector to the North

See also

- Americans in North Korea

- List of Western Bloc defectors, for other South Korean defectors who are not listed here

- North Korean defectors

References

- "Strangers At Home: North Koreans In The South" (PDF). International Crisis Group. Asia Report N°208. 14 July 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Friedman, Herbert A. (5 January 2006). "Communist Korean War Leaflets". www.psywarrior.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Koreans Admit Pilot Deserted". Eugene Register-Guard. 25 October 1953. p. 2. Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "South Korean Soldier Defects to North". The Telegraph. AP. 19 February 1985. p. 2. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Korean Employee Defects to North". The Free Lance-Star. AP. 16 February 1988. p. 2. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Joe Ritchie (13 September 1979). "South Korean, Who Joined U.S. Army, Reportedly Defected to North Korea". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "North Korea Is Promising No Harm And Cash Rewards For Defectors Who Come Back". Business Insider. 18 August 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Why Do People Keep "Re-Defecting" To North Korea?". NK News - North Korea News. 11 November 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Phenomenon of North Korean "double defectors" shows deepening divide". Scottish News - News in Scotland - Scottish Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012.

- Adam Taylor (9 August 2012). "North Korean refugees unemployment rate: twice the national average". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- Adam Taylor (26 December 2013). "Why North Korean Defectors Keep Returning Home". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Justin McCurry (22 April 2014). "The defector who wants to go back to North Korea". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- "South Korea bans North Korean defector from repatriation - UPI.com". UPI. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Will Ripley, CNN (23 September 2015). "Defector wants to return to North Korea". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "A North Korean Defector's Regret". The New York Times. 16 August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Tim Hume, CNN (28 October 2013). "South Korea intrigued by 6 who defected to Pyongyang - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "North Korea Returns South Korean 'Defectors'". VOA. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Adam Withnall (28 October 2013). "South Korean defectors flee TO North Korea 'in search of better life' - but end up in detention for up to 45 months". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "Corea del Norte - Inmigración 2019". datosmacro.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "South Korean army shoots dead 'defector'". Telegraph.co.uk. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Choi Duk Shin, 75, Ex-South Korean Envoy". The New York Times. Associated Press. 19 November 1989. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- "BBC News | ASIA-PACIFIC | South Korean defects to the North". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Would be Defector Arrested After Deportation by North". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "N. Korea Returns S. Korean Fisherman Who Attempted Defection". english.chosun.com. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- "Unidentified Ship Defects to N. Korea". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Military Under Fire After Man Defects to N.Korea". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Son of high-profile South Korean defector 'moves to North Korea'". The Guardian. 8 July 2019. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "South Korean crosses armed border in rare defection to North | Reuters".