Meuse-Rhenish

In linguistics, Meuse-Rhenish (German: Rheinmaasländisch (Rhml.)) is a term with several meanings, used both in literary criticism and dialectology.

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

As a dialectological term, it was introduced by the German linguist Arend Mihm in 1992 to denote a group of Low Franconian dialects spoken in the greater Meuse-Rhine area, which stretches in the northern triangle roughly between the rivers Meuse (in Belgium and the Netherlands) and Rhine (in Germany). It is subdivided into North Meuse-Rhenish and South Meuse-Rhenish dialects (nordrheinmaasländische (kleverländische) und südrheinmaasländische Mundarten).[1] It includes varieties of South Guelderish (Dutch: Zuid-Gelders) and Limburgish in the Belgian and Dutch provinces of Limburg, and their German counterparts in German Northern Rhineland.

In literary studies, Meuse-Rhenish (German: Rheinmaasländisch, Dutch: Rijn-Maaslands or rarely Maas-Rijnlands, French: francique rhéno-mosan) is as well the modern term for literature written in the Middle Ages in the greater Meuse-Rhine area, in a literary language that is nowadays usually called Middle Dutch.

Low Rhenish and Limburgish

Low Rhenish (German: Niederrheinisch, Dutch: Nederrijns) is the collective name in German for the regional Low Franconian language varieties spoken alongside the so-called Lower Rhine in the west of Germany. Low Franconian is a language or dialect group that has developed in the lower parts of the Frankish Empire, northwest of the Benrath line. From this group both the Dutch and later the Afrikaans standard languages have arisen. The differences between Low Rhenish and Low Saxon are smaller than between Low Rhenish and High German. Yet, Low Rhenish does not belong to Low German, but to Low Franconian.

Today, Low Franconian dialects are spoken mainly in regions to the west of the rivers Rhine and IJssel in the Netherlands, in the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, but also in Germany in the Lower Rhine area. Only the latter have traditionally been called Low Rhenish, but they can be regarded as the German extension or counterpart of the Limburgish dialects in the Netherlands and Belgium, and of Zuid-Gelders (South Guelderish) in the Netherlands.

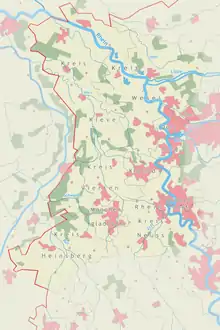

Low Rhenish differs strongly from High German. The more to the north it approaches the Netherlands, the more it sounds like Dutch. As it crosses the Dutch-German as well as the Dutch-Belgian borders, it becomes a part of the language landscape in three neighbouring countries. In two of them Dutch is the standard language. In Germany, important towns on the Lower Rhine and in the Rhine-Ruhr area, including parts of the Düsseldorf Region, are part of it, among them Kleve, Xanten, Wesel, Moers, Essen, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Oberhausen and Wuppertal. This language area stretches towards the southwest along cities such as Neuss, Krefeld and Mönchengladbach, and the Heinsberg district, crosses the German-Dutch border into the Dutch province of Limburg, where it is called Limburgish, passing cities east of the Meuse river (in both Dutch and German called Maas) such as Venlo, Roermond and Geleen, and then again crosses the Meuse between the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg, encompassing the cities of Maastricht (NL) and Hasselt (B). Thus a mainly political-geographic (not linguistic) division can be made into western (Dutch) South Guelderish and Limburgish at the west side, and eastern (German) Low Rhenish at the east side of the border. The eastmost varieties of the latter, east of the Rhine from Düsseldorf to Wuppertal, are also referred to as "Bergish" (after the former Duchy of Berg).

The Meuse-Rhine triangle

This whole region between the Meuse and the Rhine was linguistically and culturally quite coherent during the so-called early modern period (1543–1789), though politically more fragmented. The former predominantly Dutch speaking duchies of Guelders and Limburg lay in the heart of this linguistic landscape, but eastward the former duchies of Cleves (entirely), Jülich, and Berg partially, also fit in. The northwestern part of this triangular area came under the influence of the Dutch standard language, especially since the founding of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. The southeastern part became a part of the Kingdom of Prussia at the same time, and from then it was subject to High German language domination. At the dialectal level however, mutual understanding is still possible far beyond both sides of the national borders.

By including Zuid-Gelders-Kleverlandish in this continuum, we are enlarging the territory and turn the wide circle of Limburgish into a triangle with its top along the line Arnhem – Kleve – Wesel – Duisburg – Wuppertal (along the Rhine-IJssel Line). The Diest-Nijmegen Line is its western border, the Benrath line (from Eupen to Wuppertal) is a major part of the southeastern one.

Within the Dutch speaking area, the Western continuance of Low Rhenish is divided into Limburgish and Zuid-Gelders. Together they belong to the greater triangle-shaped Meuse-Rhine area, a large group of southeastern Low Franconian dialects, including areas in Belgium, the Netherlands and the German Northern Rhineland.

Classification

- Indo-European

- Germanic

- West Germanic

- Low Franconian

- Meuse-Rhenish

- Limburgish and Zuid-Gelders / Low Rhenish

- Meuse-Rhenish

- Low Franconian

- West Germanic

- Germanic

Literature

- Georg Cornelissen 2003: Kleine niederrheinische Sprachgeschichte (1300–1900) : eine regionale Sprachgeschichte für das deutsch-niederländische Grenzgebiet zwischen Arnheim und Krefeld [with an introduction in Dutch]. Geldern / Venray: Stichting Historie Peel-Maas-Niersgebied, ISBN 90-807292-2-1] (in German)

- Michael Elmentaler, Die Schreibsprachgeschichte des Niederrheins. Ein Forschungsprojekt der Duisburger Universität, in: Sprache und Literatur am Niederrhein, Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie Bd. 3, 1998, p. 15–34.

- Theodor Frings 1916 & 1917: Mittelfränkisch-niederfränkische studien.

- I. Das ripuarisch-niederfränkische übergangsgebiet, in: Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur, 41 (1916), p. 193–271.

- II. Zur geschichte des niederfränkischen, in: Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur, 42 (1917), p. 177–248.

- Irmgard Hantsche 2004: Atlas zur Geschichte des Niederrheins (= Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie 4). Bottrop/Essen: Peter Pomp (5th ed.). ISBN 3-89355-200-6

- Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.) 2004: Mittelalter an Rhein und Maas. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Niederrheins. Dieter Geuenich zum 60. Geburtstag (= Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur Nordwesteuropas 8, edited by Horst Lademacher). Münster/New York/München/Berlin: Waxmann. ISBN 3-8309-1380-X

- Arend Mihm 1992: Sprache und Geschichte am unteren Niederrhein, in: Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung, 88–122.

- Arend Mihm 2000: Rheinmaasländische Sprachgeschichte von 1500 bis 1650, in: Jürgen Macha, Elmar Neuss, Robert Peters (eds.): Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprachgeschichte. Köln enz. (= Niederdeutsche Studien 46), 139–164.

- Helmut Tervooren 2005: Van der Masen tot op den Rijn. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der volkssprachlichen mittelalterlichen Literatur im Raum von Rhein und Maas. Geldern: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 3-503-07958-0

See also

References

- Michael Elmentaler, Anja Voeste, Areale Variation im Deutschen historisch: Mittelalter und Frühe Neuzeit, with the subchapter Rheinmaasländisch (Niederfränkisch). In: Sprache und Raum: Ein internationales Handbuch der Sprachvariation. Band 4: Deutsch. Herausgegeben von Joachim Herrgen, Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Unter Mitarbeit von Hanna Fischer und Birgitte Ganswindt. Volume 30.4 of Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science / Manuels de linguistique et des sciences de communication) (HSK). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2019, p. 61ff., subchater p. 70f., here p. 70