Spanish Renaissance literature

Spanish Renaissance literature is the literature written in Spain during the Spanish Renaissance during the 15th and 16th centuries. .

| Literature of Spain |

|---|

| • Medieval literature |

| • Renaissance |

| • Miguel de Cervantes |

| • Baroque |

| • Enlightenment |

| • Romanticism |

| • Realism |

| • Modernismo |

| • Generation of '98 |

| • Novecentismo |

| • Generation of '27 |

| • Literature subsequent to the Civil War |

Overview

Political, religious, literary, and military relations between Italy and Spain from the second half of the 15th century provided a remarkable cultural interchange between those two countries. The papacy of two illustrious Valencians, Calixto III (Alfonso de Borja) and Alejandro VI (Rodrigo de Borja y Oms), narrowed cultural relations between Castile, Aragón, and Rome. From 1480, there were printers active in Spain[1] The Spanish literary works of greatest prominence were published or translated in Italy, the center of early printing.[2] This was the case with Amadís de Gaula, The Celestina, Jail of Love, the poetic compositions of Jorge Manrique, Íñigo López de Mendoza, 1st Marquess of Santillana and popular productions such as romances, carols, etc. The same thing happened in Spain with Italian works, among them the Jerusalén liberada of Torquato Tasso. Hispanic-Italian relations were very important, since they brought to the Iberian Peninsula the intellectual ferment and tastes that precipitated the Spanish Renaissance.

The Spanish Renaissance began with the unification of Spain by the Catholic Monarchs and included the reigns of Carlos I and Felipe II. For this reason, it is possible to distinguish two stages:

- Reign of Carlos I: New ideas are received and the Italian Renaissance is imitated.

- Reign of Felipe II: The Spanish Renaissance withdraws into itself and its religious aspects are accentuated.

With respect to ideology, the Renaissance mentality is characterized by:

- Esteem of the Greco-Latin world, in the light of which a new, more secular scale of values for the individual is sought.

- Humanity is the focal point of the universe (anthropocentrism), able to dominate the world and to create its own destiny.

- Reason precedes sentiment; balance, moderation and harmony prevail.

- The new ideal man is the courtier, capable as poet and soldier.

- A new conception of beauty that idealizes the present world (as opposed to heaven) not as it is, but as it should be in terms of nature, woman, and love.

The Spanish Renaissance

Classically, 1492 is spoken of as the beginning of the Renaissance in Spain; nevertheless it is complex to consider a date, due to the multiple circumstances that happened. The situation of Spain was always very complex but even so the humanism managed to maintain its innovating characteristics, in spite of the interferences that limited the study of the classic works.

An important fact is the heterogeneity of the population, a fact that dates from the year 711 when part of the peninsula was conquered by the Muslims, whose last governors were expelled from the last of their possessions in 1492 during the Reconquista. Later, the period was characterized by its vitality and renovation. The Inquisition became an organ which also depended on the State and not only on the Church.

One can speak of erudition since the Catholic Monarchs. Within this period the first important author is Antonio de Nebrija (1442–1522), with his Spanish grammar. In 1492, he published the first book of grammar in the Spanish language (titled Gramática Castellana in Spanish), which was the first grammar produced by any Romance language. At this time, Castilian became Spanish, the official language of Spain, replacing Latin.

A great patron during the Renaissance was cardinal Gonzalo Jiménez de Cisneros, whose humble origin contrasts with his austere character and with the fact that he put his greatest effort in reforming the indisciplined customs of the religious orders. He thought that the reform had to be the fruit of an educational reform, and although not an erudite, he was the maximum protector of the new studies. In 1498 he founded the University of Alcalá de Henares, that surpassed in prestige and influence all the others except the University of Salamanca, its greatest rival. The direction of his reform agreed partly with the ideas of Erasmus in a moment in which these were the booming doctrines in Europe and Spain.

During this time a work like the one by Pedro Mexía was common, who compiled miscellaneous scientific information. It is an example of the Renaissance tendency towards idealization, because of the conviction that wisdom could be extracted from the common people, whose pure tradition was thought to have conserved it, because people had always been close to nature.

Within the idealism and the humanism of the Renaissance the controversies of the colonial activity of Spain in the New World are very well represented. The main promoter was the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566), who had as basic principles: that war is irrational and opposite to civilization; that force does not have to be used against the native people, because even forced conversion to Christianity is reprehensible; that the irrationality and freedom of man demand that religion and all the other of its forms be taught only by means of a smooth and amiable persuasion.

The resurgence of the new spirit of the Renaissance is incarnated by Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546), Dominican theologian, professor at Salamanca, who rejected all argumentation based on pure metaphysical considerations because he was in favour of the study of the real problems raised by the political and social contemporary life. He was among the first to establish the basic concepts of the modern international law, based on the rule of natural law. He affirmed fundamental liberties, such as freedom of speech, communication, commerce. But these liberties were inherent to human society, within which the natives were not considered because they were underdeveloped communities, without political organization nor commerce. Consequently, he advocated a mandate system where the inferior races had to be governed by superior races, a doctrine based on natural servility, and so if the uncivilized nations refused to be voluntarily subjugated, the war was morally legitimate.

With Erasmus, the spirit of tolerance dies in Spain, as no reconciliation or commitment between Protestants and Catholics was reached, and the Counter-Reformation began; religious unity was persecuted, even within Christianity itself, so the Renaissance had finished. Nevertheless, the Spanish religiousness maintained its own parameters thanks to a new order, the Company of Jesus, founded by San Ignacio de Loyola (1491–1556). Also Neoplatonism arrived in Spain, coming from Italy.

The Renaissance poetry

The poetry of this period is divided in two schools: the Salmantine (e.g. Fray Luis de León) and the Sevillian (e.g. Fernando de Herrera).

The Salmantine School has as distinguishing characteristics:

- concise language;

- ideas expressed simply;

- realistic themes; and

- preference for short verse.

However, the Sevillian school is:

- grandiloquent;

- extremely polished;

- focused on meditation rather than feeling, more about documentation than about observation of nature and life;

- composed of long, complex verses; and

- filled with adjectives and rhetorical language.

However, this second school served as immediate base and necessary bridge to connect with the poetic movements that in the 17th century were included under the general denomination of Baroque.

The Renaissance lyric is originated from:

- The tradition, which perpetuates themes and forms of the medieval lyric. This tradition is made up of the traditional lyric, oral and popular (carols, love songs...) and the not-written lyric transmitted by the Romancero, as much as of the cultured lyric (of authors like Juan de Mena or Íñigo López de Mendoza, 1st Marquess of Santillana) and the courtesan lyric of troubadour roots gathered in the song books of which the most famous was the one of Hernando de Acuña. This traditional poetry is bound to the use of the short verse, especially eight syllables.

- The innovating current rooted in Petrarch and therefore italianizing, that will mature thanks to Boscán and Garcilaso. This current drinks in fact of the same sources as the previous one: the Provençal lyric. They handle therefore the same conception of the love as a service that dignifies the enamored one.

Its characteristics are:

- Concerning the metric used, verses (eleven syllables), strophes (lyre) and poems (sonnet) coming from Italy are adopted. Characteristic genres as the égloga (the protagonists are idealized shepherds), ode (for serious matters) or the epistle (poem in form of letter) also appear.

- The language at this time is dominated by the naturalness and simplicity, fleeing from the affectation and the carefully searched phrase. Thus the lexicon and the syntax are simple.

- The subjects preferred by the Renaissance poetry are, fundamentally, the love, conceived from the platonic point of view; the nature, as something idyllic (bucolic); pagan mythology, of which histories of Gods are reflected; and the feminine beauty, always following the same classical ideal. In relation to these mentioned subjects, several Renaissance topics exist, some of them taken from the classical world:

- The Carpe diem, whose translation would be "seize the day" or "take advantage of the moment". With it the enjoyment of the life before the arrival of the oldness is advised.

- The feminine beauty, described always following the same scheme: young blonde, of clear, calm eyes, of white skin, red lips, rosy cheeks, etc.

- The Beatus Ille or praise of the life in the field, apart from the material world, as opposed to the life in the city, with its dangers and intrigues.

- The Locus amoenus or description of a perfect and idyllic nature.

With respect to imitation and originality in the Renaissance poetry, the Renaissance poet used the models of the nature; on this base he did not put into doubt the necessity of imitating, because these procedures were justified by coming not from the reproduction of models, but from the same spirit that gathered other thoughts. If other people's creations, unavoidably dispersed because of being multiple, are recast into a unique creation, and if the spirit of the writer shines in it, nobody will be able to deny the qualification of original to it. There was a self-satisfaction component, since the sources gave prestige to the one that discovered them. Those searches mostly meant a struggle between the old and the modern, to exhibit the own culture. The writer of the time assumed the imitation as the center of his activity. The absolute originality constituted a remote ideal that was not refused, but it was not postulated to themselves demandingly, because it was a privilege granted to very little people, and in addition the possibility of reaching it with imitative means existed. In the imitation one must go to several sources that must be transformed and reduced to unit.

Garcilaso de la Vega

In the lyric poetry of the first half of the 16th century, this critic recognizes several parallel currents that converge in two great lines.

- Traditional: which perpetuates the themes and forms coming from the medieval tradition. It includes the traditional lyric (carols, little songs of love, romance texts, etc.) as much as the song book poetry of the 15th century in its loving and didactic moral side. It is bound to the use of short verses, specially the verse with eight syllables.

- Italianizing: more innovative, introducing the Petrarchian-inspired poetic models which were popular in Renaissance Italy to Spain. It reflects the development of the innovations of Juan Boscán and Garcilaso, according to the pattern of the Italian cultured lírica of their time. It is bound to the use of eleven syllables, the sonnet and diverse strophes derived from the Petrarch-like song.

A rigid dichotomy between the two currents is inappropriate since both descend from the common source of Provençal poetry. In the Spanish lyric a Petrarch-like climate already existed, coming from the troubadour background that the poets of the new style had taken up in Italy. The rise of the italianizing lyric has a key date: in 1526 Andrea Navagiero encouraged Juan Boscán to try to put sonnets and other strophes used by good Italian poets into Castilian. In Italy, enthusiasm about Greco-Latin works brought about a resurgence of feeling for the bucolic as well, in addition to the pastoral stories of the Golden Age and other classical myths that could be used to communicate feelings of love.

Garcilaso de la Vega (1501–1536) was a courtesan and soldier in imperial times. It is virtually impossible to reconstruct his external life without autobiographical details inspired in greater part by the Portuguese Isabel Freire, passing first through jealousy at her wedding, and later through the pain of her death. The poetry of Garcilaso is linked with the names of three other influences: Virgil, Petrarch and Sannazaro (from Virgil, he takes the expression of feeling; from Petrarch, metre and the exploration of mood; and from Sannazaro, the artistic level). He stood out because of the expressive richness of his verses.

The poetic trajectory of Garcilaso is forged by the experiences of a spirit shaken between contradictory impulses: to bury oneself in conformity or to take refuge in the beauty of dreams. But these states of the soul encountered traditional literary forms, which moulded the sentimental content and expression, intensifying or filtering them. Garcilaso begins to concern himself with the beauty of the outer world, with feminine beauty, with the landscape. Elements of a new style are present, that impel him to idealize love, enshrining it as a stimulus of spirituality.

Juan Boscán

Boscán, that had cultivated previously the courtesan lyric, introduced the Italian eleven-syllable verse and strophes, as well as the reasons and structures of Petrarch-like poetry in the Castilian poetry. The poem Hero and Leandro of Boscán is the first that deals with classic legendary and mythological themes. On the other hand, his Epistle to Mendoza introduces the model of the moral epistle in Spain, where he exposes the ideal of the stoic wise person. In addition, Boscán demonstrated his dominion of the Castilian by translating Il Cortegiano (1528) of the Italian humanist Baldassare Castiglione in a Renaissance model prose. In addition, he prepared the edition of the works of Garcilaso de la Vega, although he died before being able to culminate the project, reason why his widow printed the work in 1543 with the title The works of Boscán with some of Garcilaso of Vega.

Alonso de Ercilla

Alonso de Ercilla was born into a noble family in Madrid, Spain.[3] He occupied several positions in the household of Prince Philip (later King Philip II of Spain), before requesting and receiving appointment to a military expedition to Chile to subdue the Araucanians of Chile, he joined the adventurers. He distinguished himself in the ensuing campaign; but, having quarrelled with a comrade, he was condemned to death in 1558 by his general, García Hurtado de Mendoza. The sentence was commuted to imprisonment, but Ercilla was speedily released and fought at the Battle of Quipeo (14 December 1558). He was then exiled to Peru and returned to Spain in 1562. He wrote La Araucana; an epic poem[4] in Spanish about the Spanish Conquest of Chile.[5] It was considered the national epic of the Captaincy General of Chile.[6]

Other poets

Within the so-called traditional line, the figure of Cristóbal de Castillejo stands out, whose loving poems, fit to the topics of the courteous love, and satires have been admired. He has been perceived as a person full of the ideal of Erasmo and gifted with a moral superiority over the courtesan baseness. In his work there is a mixture of comedy and moral. He was against the Italianizing school, and headed the defense of the national language of the new empire, that postulated that this language would surpass and revitalize the insubstantialness and affectation of the Castilian songs of his time, already moved away from the previous models. This vitality meant the incorporation of folkloric and traditional elements, the populist Erasmo-like tendency of the proverb and the colloquy, and the literary linguistic nationalism.

Religious literature

The Renaissance imposes a division between the natural and the supernatural things, as opposed to the Middle Ages in which they were mixed in such form that God, the Virgin and the Saints took part in all type of worldly subjects with appearances and miracles. At this new time, there are worldly writers, like Garcilaso de la Vega, and authors who express religious feelings solely, as much in verse as in prosa. In the Renaissance these feelings are developed and declared widely, strongly impelled by the Counter-Reformation, the fight against the Protestant Reformation, on which the Spanish Universal Monarchy and the catholic church insisted.

The religious literature can be manifested in treaties in prose on spiritual matters (like The names of Christ of fray Luis of León), or in poems loaded of spirituality (San Juan de la Cruz). The forms of religious life, denominated "ascetic" and "mystic", were expressed in both ways.

- The ascetic tries to perfect the people urging them to strictly fulfill the Christian obligations, and instructing them on it. Important writers are fray Luis de Granada (1504–1588), San Juan de Ávila (1500–1569) and fray Juan de los Ángeles (1536–1609).

- The mystic tries to express the prodigies that some privileged people experiment in their own soul when entering in communication with God. The mystics preferredly wrote in verse (San Juan de la Cruz), although they did not renounce to the prose (Santa Teresa de Jesús).

Fray Luis de León

Fray Luis de León (Cuenca, Spain, 1527 – 1591) was a Spanish Augustinian friar. In 1561 he obtained a chair in Theology at the University of Salamanca.

His major works in prose are:

- The Perfect Wife, which advises all young women on the proper behavior and duties of a married woman.

- The Names of Christ, a guide to the layman about the essential principles of the Church.

- A translation of the Song of Songs. He was denounced to the Inquisition for translating it and he was imprisoned for four years.

- A Commentary on the Book of Job, aiming to make the Scripture available to those who could not read Latin.

His most important poetic works are twenty-three poems, among them:

- The Life Removed, about the peace, happiness, and liberty assured to those who travel the hidden path.

- Ode to Salinas, written for his friend Francisco de Salinas.

San Juan de la Cruz

San Juan de la Cruz (Ávila, 1542–1591) was a Carmelite friar. He studied philosophy at the University of Salamanca. He cooperated with Saint Teresa of Avila in the reformation of the Carmelite order. In 1577, following his refusal to relocate after his superior's orders, he was jailed in Toledo, and later freed. His two most important poems are:

- The Spiritual Canticle, an eclogue in which the bride (representing the soul) searches for the bridegroom (representing Jesus Christ).

- The Dark Night of the Soul, that narrates the journey of the soul from her bodily home to her union with God.

He also wrote three treatises on mystical theology and the Ascent of Mount Carmel, a more systematic study of the ascetical effort of a soul looking for perfect union with God.

Santa Teresa de Jesús

Santa Teresa de Jesús (Ávila, 1515 – 1582) was a Carmelite nun. She entered the monastery leaving her parents' home secretly. She experienced periods of spiritual ecstasy through the use of the devotional book. Various friends suggested that her knowledge was diabolical, not divine, but her confessor reassured her of the divine inspiration of her thoughts. She was very active as a reformer of her order, and she founded many new convents. Her most important writings are:

- Her Autobiography, The Life of Teresa of Jesus.

- The Way of Perfection.

- The Interior Castle, where she compared the soul with a castle.

- Relations, an extension of her autobiography.

Other smaller works are Concepts of Love and Exclamations. Besides, the Letters.

Didactic and religious prose

During the reign of Felipe II, from 1557 to 1597, the religious prose had its greater boom in Spain. The religiosity of the monarch, the spirit of the Counterreformation and the customs of the time were part in the extraordinary importance that this genre reached. The didactic and religious literature is vast, it includes:

- The Apologetics, which displays arguments for the religion;

- The Ascetic, that tends to instil the rules of the moral; and

- The Mystic, that searches for the knowledge of God within the own spirit, by means of the contemplation and the meditation. The production of the mystics of the 16th century is of great importance, mainly for the growth and robustness of the language.

The Renaissance prose

.jpg.webp)

Great part of the narrative subgenera of the 15th century continued to be alive throughout the 16th century. The sentimental novels of the late fifteenth / early sixteenth century—particularly Juan de Flores's Grisel y Mirabella, Diego de San Pedro's Cárcel de amor and Fernando de Rojas's La Celestina—continued to enjoy enormous European success.

Chivalric romance

Amadís de Gaula by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo[7][8][9] is a landmark work among the chivalric romances which were in vogue in sixteenth-century Iberian Peninsula, although its first version, much revised before printing, was written at the onset of the 14th century. In the decades following its publication, dozens of sequels of sometimes minor quality were published in Spanish, Italian, and German, together with a number of other imitative works. Montalvo cashed in with the continuation Las sergas de Esplandián (Book V), and the sequel-specialist Feliciano de Silva (also the author of Second Celestina) added four more books including Amadis of Greece (Book IX). Miguel de Cervantes wrote Don Quixote as a burlesque attack on the resulting genre. Cervantes and his protagonist Quixote, however, keep the original Amadís in very high esteem. The Picaresque novel stands in contrast to the Chivalric romance.[10]

Pastoral novel

The pastoral novel is of Italian origin, like the sentimental novel. About the year of 1558 the first Spanish text pertaining to this genre appeared: La Diana, written by Jorge de Montemayor. The success of this type of narrative encouraged great authors of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, such as Lope de Vega (La Arcadia) and Miguel de Cervantes (La Galatea), to cultivate it.

Picaresque novel

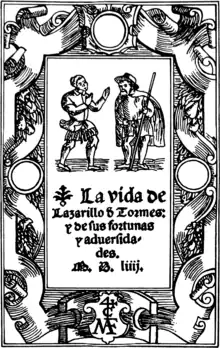

The Lazarillo, of anonymous author, was published in 1554 and narrates the life of a boy, Lázaro de Tormes, from his birth until he marries the servant of an archpriest in Toledo. Throughout that time he serves several masters who mistreat him and give him very little to eat. This book inaugurated the picaresque novel and it stands out within the production of the literature of the Golden Century because of its originality, since it represents a literature based on the reality, as opposed to the idealism or the religiosity of the literature of the time and immediately previous (books of chivalries, sentimental novel, etc.) The episodes are articulated through the life of the rascal. The picaresque novel, as literary genre, has the following characteristics:

- The story is autobiographical.

- The narration follows a chronological order.

- The irony and the dialogue are two of the most used resources to develop the argument and to express the critic in the book.

- The protagonist is a rascal; who:

- belongs to the lower social class, being almost a delinquent;

- is a vagabond;

- acts induced by the hunger;

- looks for the way to improve his life;

- lacks ideals.

See also

References

- Febvre, Lucien; Martin, Henri-Jean (1976): "The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800", London: New Left Books, quoted in: Anderson, Benedict: "Comunidades Imaginadas. Reflexiones sobre el origen y la difusión del nacionalismo", Fondo de cultura económica, Mexico 1993, ISBN 978-968-16-3867-2, pp. 58f.

- Borsa 1976, p. 314; Borsa 1977, p. 166−169

- Alonso de Ercilla, Biografías y Vidas.

- Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga: La Araucana (in Spanish).

- Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Spanish soldier and poet, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Spanish soldier and poet, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Rodríguez de Montalvo, Garci, s. XVI" (in Spanish). Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library. 19 June 2020.

- "Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo". biografiasyvidas.com. Biografias y Vidas. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo". La Real Academia de la Historia. Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Oxford English Dictionary.

Sources

- Borsa, Gedeon (1976), "Druckorte in Italien vor 1601", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch: 311–314

- Borsa, Gedeon (1977), "Drucker in Italien vor 1601", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch: 166–169

- David T. Gies (Ed.). The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature. Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-521-80618-6.

-John_of_the_Cross-1656.jpg.webp)