Spanish battleship Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII was the second of three España-class dreadnought battleships built in the 1910s for the Spanish Navy. Named after King Alfonso XIII of Spain, the ship was not completed until 1915 owing to a shortage of materials that resulted from the start of World War I the previous year. The España class was ordered as part of a naval construction program to rebuild the fleet after the losses of the Spanish–American War; the program began in the context of closer Spanish relations with Britain and France. The ships were armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) guns and were intended to support the French Navy in the event of a major European war.

.jpg.webp) Alfonso XIII in 1932, after having been renamed España | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Alfonso XIII (renamed España in 1931) |

| Namesake | King Alfonso XIII of Spain; after 1931, the country of Spain |

| Builder | SECN, Naval Dockyard, El Ferrol, Spain |

| Laid down | 23 February 1910 |

| Launched | 7 May 1913 |

| Completed | 16 August 1915 |

| Fate | Sunk by naval mine, 30 April 1937 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | España-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 140 m (460 ft) o/a |

| Beam | 24 m (79 ft) |

| Draft | 7.8 m (26 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h) |

| Range | 5,000 nmi (9,300 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Complement | 854 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Despite the reason for the ships' construction, Spain remained neutral during World War I. Alfonso XIII's early career passed largely uneventfully with routine training exercises in Spanish waters, though she was used to assist civilian vessels in distress and her crew was deployed to suppress civil unrest in Spain. In the 1920s, she took part in the Rif War in the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, where her sister España was wrecked. In 1931, Alfonso XIII abdicated and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed; the new republic sought to erase remnants of the royal order, and so Alfonso XIII was renamed España. As part of cost-cutting measures, the ship was then reduced to reserve. Plans to modernize España and her sister Jaime I in the mid-1930s came to nothing when the Spanish coup of July 1936 initiated the Spanish Civil War.

At the start of the conflict, the crew murdered the ship's officers and attempted to resist the Nationalist rebels in Ferrol, but after the Nationalists seized coastal artillery batteries, they surrendered. España then became the core of the Nationalist fleet and she was used to enforce a blockade of the north coast of Spain, frequently patrolling and stopping freighters that attempted to enter the Republican-controlled ports of Gijón, Santander, and Bilbao. During these operations on 30 April 1937, she was fatally damaged when she accidentally struck a mine that had been laid by a Nationalist minelayer. Most of her crew was evacuated by the destroyer Velasco before España capsized and sank; only four were killed in the sinking. The wreck was discovered and examined in 1984.

Design

Following the destruction of much of the Spanish fleet in the Spanish–American War of 1898, the Spanish Navy began a series of failed attempts to begin the process of rebuilding. After the First Moroccan Crisis strengthened Spain's ties to Britain and France and public support for rearmament increased in its aftermath, the Spanish government came to an agreement with those countries for a plan of mutual defense. In exchange for British and French support for Spain's defense, the Spanish fleet would support the French Navy in the event of war with the Triple Alliance. A strengthened Spanish fleet was thus in the interests of Britain and France, which accordingly provided technical assistance in the development of modern warships, the contracts for which were awarded to the Spanish firm Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN), which was formed by the British shipbuilders Vickers, Armstrong Whitworth, and John Brown & Company. The vessels were authorized some six months after the British had completed the "all-big-gun" HMS Dreadnought, and after discarding plans to build pre-dreadnought-type battleships, the naval command quickly decided to build their own dreadnoughts.[1]

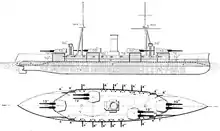

Alfonso XIII was 132.6 m (435 ft) long at the waterline and 140 m (460 ft) long overall. She had a beam of 24 m (79 ft) and a draft of 7.8 m (26 ft); her freeboard was 15 ft (4.6 m) amidships. The ship displaced 15,700 t (15,500 long tons) as designed and up to 16,450 t (16,190 long tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of four-shaft Parsons steam turbines driving four screw propellers, with steam provided by twelve Yarrow boilers. The engines were rated at 15,500 shaft horsepower (11,600 kW) and produced a top speed of 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph). Alfonso XIII had a cruising radius of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew consisted of 854 officers and enlisted men.[2]

Alfonso XIII was armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) 50-caliber guns, mounted in four twin gun turrets. One turret was placed forward, two were positioned en echelon amidships, and the fourth was aft of the superstructure.[2] This mounting scheme was chosen in preference to superfiring turrets, as was done in the American South Carolina-class battleships, to save weight and cost.[3] For defense against torpedo boats, she carried a secondary battery that consisted of twenty 102 mm (4 in) guns mounted individually in casemates along the length of the hull. They were too close to the waterline, however, making them unusable in heavy seas. She was also armed with four 3-pounder guns and two machine guns. Her armored belt was 203 mm (8 in) thick amidships; the main battery turrets were protected with the same amount of armor plate. The conning tower had 254 mm (10 in) thick sides. Her armored deck was 38 mm (1.5 in) thick.[2]

Service history

Early career

The keel for Alfonso XIII was laid down at the SECN shipyard in Ferrol on 23 February 1910 and her completed hull was launched on 7 May 1913. Fitting-out work was delayed by the start of World War I in July 1914, since much of the equipment, including her guns and fire-control systems, were supplied by British manufacturers that were now occupied with production for the British war effort. Alfonso XIII was completed on 16 August 1915, albeit with an improvised fire-control system that was secured through neutral countries. After Italy, a member of the Triple Alliance, declared neutrality at the start of the war, Spain followed suit, since the participation of its fleet in the pre-war agreements with Britain and France had been predicated on the need to reinforce the French fleet against the combined Italian and Austro-Hungarian navies. After entering service, Alfonso XIII sailed with her sister España to Santander, where the ship's namesake, King Alfonso XIII was aboard his yacht Giralda. The two battleships then took part in training exercises off Galicia. At the end of the year, Alfonso XIII's crew won the Spanish Christmas Lottery.[2][4]

The peacetime routine of the Spanish fleet included training exercises, frequently held off Galicia, and a fleet review off Santander during the King's usual summer vacation there. The year 1916 passed uneventfully until September, when Alfonso XIII joined the search for the destroyer Terror, which had encountered severe weather in the Bay of Biscay and had been disabled by storm damage. The battleship assisted the tugboat Antelo in April 1917 after the latter vessel had run aground off Cabo Prior. The tug had been carrying a load of mines, which Alfonso XIII took aboard to lighten Antelo so she could be pulled free. By this time, socialist and anarchist groups in Spain campaigned for a general strike and a revolution against the monarchy, prompting the military governor of Bilbao to request Alfonso XIII's presence to help restore order in August. The ship's landing party went ashore to guard a rail line and several mines. In a clash with revolutionaries, one man from the ship's crew was killed and several were injured, while twenty-two revolutionaries were arrested and held aboard the ship. Alfonso XIII again helped to suppress striking workers in early 1919, when, after having sailed to Barcelona for the commissioning of the submarine Narciso Monturiol, she arrived in the midst of the La Canadiense strike against the Barcelona Traction company. Alfonso XIII again sent men ashore to protect the company during the strike that lasted for 44 days.[5]

In 1920, the Spanish Navy embarked on a series of long-distances cruises to show the flag, in part to demonstrate its growing power. Alfonso XIII was sent to tour the Caribbean Sea and visit the United States, departing Ferrol for Havana, Cuba, by way of a stop in the Canary Islands on 22 June. On arriving in Havana on 9 July, she met an enthusiastic reception that belied the Cuban rebellion against Spanish rule in the 1890s. Alfonso XIII then steamed to Puerto Rico, which had also been part of the Spanish colonial empire until the war of 1898, and where the ship was also warmly received.[5] The ship also visited Annapolis in the United States; the unprotected cruiser USS Reina Mercedes, a former Spanish cruiser that had been captured during the war with the United States and commissioned into the US Navy, flew the Spanish flag to honor her visit.[6] Alfonso XIII concluded the tour with a stop in New York City in mid-October, after which she re-crossed the Atlantic, arriving back in Spain in November. In April 1921, the ship visited Lisbon, Portugal, during ceremonies held to commemorate the country's soldiers who had been killed during World War I.[5]

Rif War

Throughout the early 1920s, she provided naval fire support to the Spanish Army in its campaigns in Morocco during the Rif War that had broken out in mid-1921. At the start of the conflict on 16 July 1921, Alfonso XIII was operating on the northern coast of Spain. She took on a full stock of coal at Santander on 22 July and immediately got underway to provide gunfire support to Spanish forces in the colony. She arrived off Melilla on 10 August and began shelling rebel positions the next day. Her landing party went ashore to reinforce the Spanish soldiers in the area.[7] On 17 September, she and España bombarded Rif positions south of Melilla while Spanish Foreign Legion troops assaulted the positions.[8] Alfonso XIII continued to operate off the coast of Spanish Morocco through 1922, including a bombardment of Rif artillery batteries that were being used to target coastal shipping. The batteries scored several hits on the ship, but she was not significantly damaged and her crew suffered no casualties.[7]

In August 1923, she participated in the first combined arms operation in Spanish military history that included aircraft, warships, and ground forces operating together.[9] The fleet was used to support an amphibious assault west of Melilla. On 26 August, during the operation, España was wrecked off Cape Tres Forcas. Alfonso XIII came alongside to take off her crew, ammunition, and other supplies to lighten the vessel so she could be pulled free. Over the next year, work continued to refloat the vessel that ended in failure when a storm destroyed the ship in November 1924.[7] During this period, tensions over the European colonial holdings in North Africa—predominantly stoked by Italy's fascist leader Benito Mussolini over the perceived lack of prizes for Italy's eventual participation in World War I on the side of the Entente—had led to a rapprochement between Italy and Spain in 1923, which was at that time ruled by the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera. Primo de Rivera sent a fleet consisting of Alfonso XIII, her sister Jaime I, the light cruiser Reina Victoria Eugenia, two destroyers, and four submarines to visit the Italian fleet in late 1923. They departed Valencia on 16 November and stopped in La Spezia and Naples, arriving back in Barcelona on 30 November.[5]

By 1925, the Rif rebels had widened the war by surrounding and taking over several French positions in neighboring French Morocco. Spain and France planned a major landing at Alhucemas, consisting of some 13,000 soldiers, 11 tanks, and 160 aircraft, to attack the core rebel territory in early September. The Spanish Navy supplied Alfonso XIII, Jaime I, four cruisers, the seaplane tender Dédalo, and several smaller craft, with Alfonso XIII serving as the Spanish flagship. The French added the battleship Paris, two cruisers, and several other vessels. Both fleets provided gunfire support as the ground forces landed on 8 September; the amphibious assault was a success, and after heavy fighting over the next two years, and by 1927 the last Rifian rebels surrendered to the allied troops.[7]

Decommissioning and planned modernization

After completing the annual training routine in 1927, Alfonso XIII embarked her namesake and his wife Victoria Eugenie in September for a cruise along the coast of Galicia. They returned to the ship in October to visit Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa, where rebellions against Spanish rule had recently been suppressed. Alfonso XIII was escorted by the cruisers Reina Victoria Eugenia and Mendez Nunez and the destroyer Bustamante. Alfonso XIII participated in a fleet review with British, French, Italian, and Portuguese warships during the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition that began in May and continued until January 1930. By this time, the effects of the Great Depression had spurred significant domestic opposition to the regime of Primo de Rivera, leading to his resignation on 28 January, and ultimately to Alfonso XIII's exile in April 1931. On 17 April, three days after the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, the new government ordered Alfonso XIII renamed España.[2][10]

Immediately thereafter, the new government began a series of cost-cutting measures to offset the deficits that had been incurred during the Rif War, and as a result, both España and Jaime I were placed in reserve in Ferrol on 15 June 1931. España was decommissioned on 15 November and remained out of service for the next five years, during which time some of her secondary battery and anti-aircraft guns were removed for use ashore. By the early 1930s, the warming of Spanish relations with Italy proved to be short-lived, owing to Alfonso XIII's choice of Rome as his residence in exile and the Spanish government's preference for republican France over Fascist Italy. Plans to modernize the España-class battleships traced their origin to the 1920s, but the increased risk of conflict with Italy by the mid-1930s put increased pressure to begin the work.[11] One proposal, advanced in 1934, advocated rebuilding the ships into analogs to the German Deutschland-class cruisers with new oil-fired boilers. The ships' hulls would have been lengthened, and the main battery turrets rearranged so they would all be on the centerline. The ships' secondary batteries would have been replaced with dual-purpose (DP) 120 mm (4.7 in) guns. The plan ultimately came to nothing, the result of financial weakness during the Great Depression and continued political instability.[12][13]

The finalized plan for España and Jaime I involved increasing the height of the wing turrets' barbettes, improving their fields of fire and allowing them to fire over the new secondary battery, which was to consist of twelve 120 mm DP guns placed on the upper deck in open mounts. A new anti-aircraft battery of either ten 25 mm (1 in) or eight 40 mm (1.6 in) guns were to be fitted. Other changes were to be made to improve fire-control systems, increase crew accommodation spaces, and install anti-torpedo bulges, among other improvements. Work was slated to begin in early 1937, and a limited refit was conducted in 1935–1936 in preparation for her recommissioning. Her fore and aft turrets were restored to operational status (though the wing turrets remained out of service) and her boilers were re-tubed. The scheduled modernization was interrupted by the Spanish coup of July 1936, which plunged the country into the Spanish Civil War.[14]

Spanish Civil War and loss

.svg.png.webp)

When the coup, led by Francisco Franco, against the Republican government began on 17 July, España was at anchor in Ferrol, in use as a barracks ship. After a brief period of uncertainty, Lieutenant Commander Gabriel Rozas, the acting commander of España, ordered a landing party to go ashore, though he refused to explain his intentions, prompting elements of the crew to murder Rozas and several other officers. They then went ashore to assist the Republican forces attempting to break into the Ferrol Arsenal, then held by Nationalist rebels. They were repulsed by Nationalist fire and returned to the ship. Some army detachments, including some coastal artillery units around the harbor, sided with Franco. The destroyer Velasco also defected to the Nationalist side. An artillery duel between the batteries and Velasco on the Nationalist side and España and the cruiser Almirante Cervera, the crew of which also decided to side with the government, resulted in considerable destruction in the harbor and significant damage to Velasco. After two days of fighting, the crews of España and Almirante Cervera reached a negotiated settlement with the Nationalists who had gained control of the harbor, surrendering their vessels to the Nationalists.[15][16]

With the shipyard under Nationalist control, work began to ready España for offensive operations as quickly as possible. She set sail on 12 August; by that time, her wing turrets were still not operational, and she carried only twelve of her 102 mm guns. The crew was composed of volunteers and cadets from the Escuela Naval Militar (Naval Academy) in Marín. In company with Almirante Cervera and the repaired Velasco, she patrolled the coast of Cantabria and enforced a blockade of the northern coast of Spain. The Republican government designated the ships as pirate vessels on 14 August, while they patrolled as far east as the French border. On 15 August, España bombarded Republican positions in Gijón, which housed significant industrial resources. She and Almirante Cervera then shelled fortifications in Gipuzkoa that blocked the advance of Nationalist forces; over the span of the next few days, she fired 102 shells from her main battery. The ship returned to Ferrol on 20 August, where her port wing turret was returned to service.[17]

.svg.png.webp)

On 25 August, España sortied in company with Velasco to make further attacks on the Republican-held coast between Santander and San Sebastián. They captured the Republican freighter SS Kostan (1,857 GRT) on 26 August and later seized the small fishing boat Peñas (209 GRT) before returning to Ferrol on 1 September. She sortied again to bombard Gijón again shortly thereafter and arrived back in Ferrol to be dry-docked for maintenance on 14 September. In response to these attacks, the Republicans sent a flotilla of five submarines from the Mediterranean, though one was sunk by Nationalist forces en route. They also briefly deployed Jaime I, a pair of light cruisers, and six destroyers to Gijón, arriving on 25 September, but the squadron departed already on 13 October without having engaged España or any other elements of the Nationalist fleet. España was still dry-docked during this period, and she was ready to go to sea again by mid-October. On the 21st, she captured a pair of fishing boats—Apagador (210 GRT) and Musel (165 GRT)—and on 30 October, she seized the freighter SS Manu (3,314 GRT). Early that morning, while España was on patrol, the submarine C-5 launched four torpedoes at the ship in two attacks, but all four missed. The battleship seized another freighter the next day: SS Arrate-Mendi (2,667 GRT).[18]

España underwent a refit in November that included the installation of four German-supplied 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK C/30 anti-aircraft guns and their corresponding fire-control directors and a pair of 2 cm (0.79 in) Flak 30 autocannon. She returned to service by December for further attacks on the Republican coast. On 20 December, she attacked El Musel, the port of Gijón, where the Republican destroyer José Luis Díez and other Republican vessels were anchored. She was joined in the attack by Velasco and the auxiliary cruisers Dómine and Ciudad de Valencia, though they failed to sink the Republican ships. On 30 December, España shelled the lighthouse at Cabo Mayor near Santander. Republican bombers attacked Ferrol in early January 1937 but inflicted little damage. At the same time, the Republicans laid a series of defensive minefields off Gijón and Santander. España captured the Norwegian freighter SS Carrier (3,105 GRT) on 22 January and three days later, she seized the coaster Alejandro (345 GRT). The ship, escorted again by Velasco, carried out another bombardment of Bilbao in February.[18] España seized the Republican freighter SS Mar Báltico with a cargo of iron ore on 13 February.[19]

After returning to Ferrol, she once again entered the dry dock for maintenance that lasted until 3 March. Another patrol along the northern coast followed immediately after España emerged from the dry dock and on 8 March, she stopped the freighter Achuri (2,733 GRT). While on patrol on 30 March, she encountered José Luis Díez but neither side pressed the attack. The next day, she captured the merchant ship Nuestra Señora del Carmen (3,481 GRT); during the seizure, a group of Republican aircraft attacked the ship but inflicted no damage. She also came under fire from coastal artillery that day, but again emerged unscathed. The battleship returned to shell El Musel on 13 April in another failed attempt to sink José Luis Díez. During her patrols in March and April, she repeatedly encountered units of the Royal Navy that had been sent to ensure that British-flagged vessels safely passed through the Nationalist blockade.[18] A pair of these incidents took place on 30 April; while searching for blockade runners off Santander, España and Velasco encountered the British steamer SS Consett, which was fired upon by España and forced to sail away,[20] assisted by the destroyer HMS Forester.[21][22]

Later that morning, at around 07:00, the Nationalist vessels spotted the British steamer SS Knistley. Velasco fired warning shots to force the freighter to alter course, but when España turned to support Velasco, she inadvertently entered one of the minefields that Nationalist minelayers had set in an attempt to block the port. She struck one of the mines at 07:15, which detonated against her port side engine room and boiler room, tearing a large hole in the hull and causing significant flooding.[18] España took on a list to port but remained afloat for some time, which allowed Velasco to come alongside and evacuate most of her crew, apart from three men who had been killed by the mine explosion. A fourth man died of his wounds aboard Velasco. During the evacuation, Republican aircraft launched three strikes on the vessels, but anti-aircraft gunners aboard both ships successfully drove them off. By around 08:30, España's crew had been taken off. Her list was increasing, and by the time Velasco departed, her decks were awash. Shortly thereafter, she capsized to port and sank.[23]

Wreck

In May 1984, divers from the Spanish Navy's salvage vessel Poseidon located España's wreck at a depth of about 60 m (200 ft), lying upside down, displaying the large hole created by the mine explosion. Contemporary, official reports from the Nationalist government claimed that the sinking had been the result of a Republican mine that had broken loose from its mooring, but an examination of the wreck proved that it had been a Nationalist mine, making the loss of España one of the largest self-inflicted casualties in naval history. Several proposals to raise the wreck to be scrapped have been made since her discovery, but the cost of such an enterprise have prevented any work being done.[24]

Notes

- Rodríguez González, pp. 268–273.

- Sturton, p. 378.

- Fitzsimons, p. 856.

- Rodríguez González, pp. 276–278, 282.

- Rodríguez González, p. 283.

- Reina Mercedes.

- Rodríguez González, p. 284.

- Alvarez, p. 51.

- Alvarez, pp. 107–108.

- Rodríguez González, pp. 283–285.

- Rodríguez González, p. 285.

- Garzke & Dulin, pp. 438–439.

- Rodríguez González, p. 286.

- Rodríguez González, pp. 285–286.

- Rodríguez González, p. 287.

- Beevor, p. 64.

- Rodríguez González, pp. 287–288.

- Rodríguez González, p. 288.

- Moreno de Alborán y de Reyna, p. 629.

- Heaton, p. 51.

- Fernández, p. 64.

- Alcofar Nassaes 1976, p. 296.

- Rodríguez González, pp. 288–289.

- Rodríguez González, p. 289.

References

- Alcofar Nassaes, José Luis (1976). La marina italiana en la guerra de España (in Spanish). Editorial Euros. ISBN 978-84-7364-051-0.

- Alvarez, Jose (2001). The Betrothed of Death: The Spanish Foreign Legion During the Rif Rebellion, 1920–1927. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-07341-0.

- Beevor, Antony (2000) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35281-4.

- Fernández, Carlos (2000). Alzamiento y guerra civil en Galicia: 1936–1939 [Uprising and Civil War in Galicia: 1936–1939] (in Spanish). La Coruña: Ediciós do Castro. ISBN 978-84-8485-263-6.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard (1978). "España". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. Vol. 8. Milwaukee: Columbia House. pp. 856–857. ISBN 978-0-8393-6175-6.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Heaton, Paul Michael (1985). Welsh Blockade Runners in the Spanish Civil War. Risca: Starling Press. ISBN 978-0-9507714-5-8.

- Moreno de Alborán y de Reyna, Salvador (1998). La guerra silenciosa y silenciada: historia de la campaña naval durante la guerra de 1936–39 [The Silent and Silenced War: History of the Naval Campaign During the War of 1936–39] (in Spanish). Vol. 3. Madrid: Gráficas Lormo. ISBN 978-84-923691-0-2.

- "Reina Mercedes". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 23 September 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (2018). "The Battleship Alfonso XIII (1913)". In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. pp. 268–289. ISBN 978-0-87021-906-1.

- Sturton, Ian (1985). "Spain". In Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 375–382. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

Further reading

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0-86101-142-1.

- Lyon, Hugh; Moore, John Evelyn (1978). Encyclopedia of the World's Warships: A Technical Directory of Major Fighting Ships from 1900 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0-86101-007-3.

External links

- Launching of the battleship Alfonso XIII Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine – 1913 silent newsreel footage from the Filmoteca Española.