Spiti

Spiti (pronounced as Piti in Bhoti language) is a high-altitude region of the Himalayas, located in the north-eastern part of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The name "Spiti" means "The middle land", i.e. the land between Tibet and India.[2] Spiti incorporates mainly the valley of the Spiti River, and the valleys of several rivers that feed into the Spiti River. Some of the prominent side-valleys in Spiti are the Pin valley and the Lingti valley. Spiti is bordered on the east by Tibet, on the north by Ladakh, on the west and southwest by Lahaul, on the south by Kullu, and on the southeast by Kinnaur. Spiti has a cold desert environment.[3] The valley and its surrounding regions are among the least populated regions of India. The Bhoti-speaking local population follows Tibetan Buddhism.

| Spiti | |

|---|---|

Spiti River upstream of Kaza | |

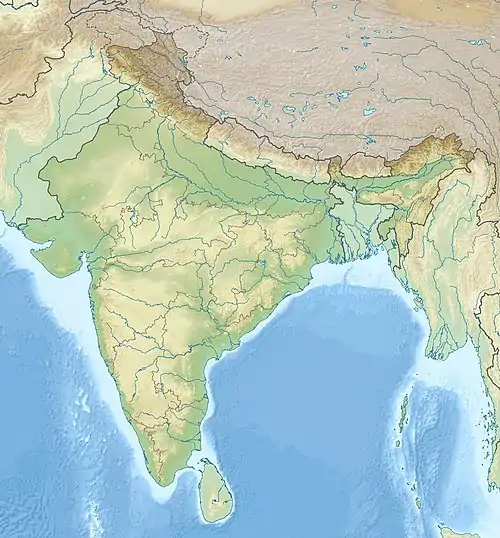

Spiti Location of Spiti Valley in Himachal Pradesh  Spiti Location of Spiti Valley in India | |

| Floor elevation | 2,950–4,100 m (9,680–13,450 ft)[1] |

| Geography | |

| Country | India |

| State | Himachal Pradesh |

| District | Lahaul and Spiti |

| Population centers | Losar, Kaza, Tabo, Sumdo, Chango |

| Coordinates | 32°14′49″N 78°03′08″E |

| River | Spiti river |

.jpg.webp)

Traditionally, agriculture was for subsistence, but has shifted to cash crops in the past few decades. Spiti is a popular destination for photography, homestay tourism, and adventure tourism of various kinds, including winter sports.

Etymology

The name "Spiti" is derived from "Piti", which means "the middle land" as the valley is surrounded on all sides by mountain ranges that separate it from former empires. These include Ladakh to the north, Tibet to the east, Bushahr to the south and Kullu to the west.[2]

Some believe that the name Piti is a contraction of Ashwapati, a legendary ruler of Pin Valley in the time of the Mahabharata. Ashwapati means "lord of horses" and Pin Valley was famous for its horse breeds. Others attribute the name to a Tibetan dacoit named Spiti Thakur. Based in Spiti valley, the Thakur gangs raided the upper parts of Kullu, before the Sen kings established their rule.[2]

History

Pre-historical period

There is evidence of very early human habitation in the Spiti valley, primarily through its rich heritage of pre-Buddhist rock art. Spiti's rock art is thought to have been produced over a wide period of time, with the earliest examples dating back nearly 3,000 years. Spiti's rock art has been categorized, based on differences of the designs depicted, into the following periods: the Late Bronze Age (c.1500–800 BCE), the early Iron Age (c.800–500 BCE), the Iron Age (c.500–100 BCE), the Protohistoric period (100 BCE–650 CE), Early Historic Period (650–1000 CE), Vestigial Period (1000–1300 CE), and the Late Historical Period (post-1300 CE).[4]

The period from the mid-7th century to the early 19th century

There is some evidence to show that Spiti was a part of the western Tibetan kingdom of Zhang Zhung until the mid-7th century CE.[4][5] Buddhism first came to Spiti likely through the Second Diffusion of Buddhism into Tibet, and it was at this time that the Tabo monastery was built (996 CE).[6] In the 10th century, Spiti was part of the kingdom of Ngari Khorsum established by Kyide Nyimagon of the Tibetan royal lineage.

After Kyide Nyimagon's death, Zanskar and Spiti were given to his youngest son Detsukgon, while the eldest son Lhachen Palgyigon became the King of Ladakh. After that, the history of Spiti was linked with the history of Ladakh for a long time. Local rulers had the title of Nonos. They were either descendants of a native family of Spiti or chiefs sent to look after the affairs of Spiti by the rulers of Ladakh. This region became autonomous whenever the rulers of Ladakh were weak. However the rulers of Spiti periodically sent tributes to Ladakh, Chamba and Kullu.[7]

Spiti became practically free after the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War of 1679–1683. This prompted Man Singh, Raja of Kullu, to invade Spiti and establish a loose control over this principality. Later on, in the 18th century, control once again passed back to Ladakh. An official was sent from Leh as Governor, but he usually went away after the harvest time, leaving the local administration in the hands of the Wazir or Nono. There was a headman for a group of villages for day-to-day administrative affairs.[7] Spiti briefly came under the Dogra rule (as part of the Sikh Empire) between 1842 and 1846, after which it was annexed to the British Empire.

Colonial period

Under the Treaty of Amritsar (1846), Spiti alongside Lahaul was split off from the erstwhile kingdom of Ladakh, and came under direct British administration.[8] Mansukh Das, hereditary Wazir of Bushahr, was entrusted with the local administration of this region from 1846 to 1848. The Wazir had to pay the British revenue of only Rs. 700 annually for the whole of Spiti. In 1849, Spiti came directly under the control of the Assistant Commissioner, Kooloo (Kullu).[9]: 132 Kullu was a sub-division of Kangra district, Punjab. Now, the Nono of Kyuling in Spiti was made incharge of collecting and submitting revenues from Spiti to the British. In 1941, Spiti was made part of the Lahaul tehsil (sub-division) of Kullu district, with its headquarters at Keylong.

Post-Independence period

After the formation of Lahaul & Spiti into a district in 1960, Spiti was formed into a sub-division with its headquarter at Kaza.[10] Lahaul and Spiti district was merged with Himachal Pradesh on 1 November 1966 on enactment of the Punjab Reorganisation Act.

Geography

The Spiti valley is located between the Kunzum range in the NW to Khab on the Sutlej river in Kinnaur in the SE. The Spiti River originates from the base of the 6,118 m (20,073 ft) K-111 peak.[9]: 27 The Taktsi tributary flows out of the Nogpo-Topko glacier, near Kunzum La 150 km (93 mi), the Spiti ends in the Satluj at Khab. The Pin, Lingti and Parachu as the major tributaries. The catchment area of the Spiti river is about 6,300 km2 (2,400 sq mi). Situated in the rain shadow of the main Himalayan range, Spiti does not benefit from the South-West monsoon that causes widespread rain in most parts of India from June to September. The river attains peak discharge in late summers due to glacier melting.[11]

There are two distinct parts of the Spiti valley. In the upper valley from Losar to Lingti, the river is braided with a very wide river bed, though the water channel is narrow.[11][9]: 30–31 The valley floor has ancient sedimentary deposits, and the sides have extensive scree slopes. The lower valley runs from Lingti to Khab. Here, the meandering river has incised channels and gorges about 10–130 m (33–427 ft) deep in the sedimentary deposits and bedrock. Tributaries and other streams join at right angles, indicating neotectonic activity in the past few million years.[11]

Steep mountains rise to very high altitudes on either side of the Spiti River and its numerous tributaries. The highest peak in the Parung range to the NE has an altitude of 7,030 m (23,064 ft) and on the SW side, is Manirang Peak at 6,598 m (21,646 ft). The mountains are barren and largely devoid of trees except for a few stunted willows and scattered trees in a some villages.[9]: 14, 29 The main settlements along the Spiti River and its tributaries are Kaza and Tabo.[12]

Geology

Over millennia, the Spiti River and its tributaries such as the Pin River, have cut deep gorges in the uplifted sedimentary strata. As vegetation is sparse, the rock strata in the steep cliffs are easily visible to the geologist, without excavation or drilling. Thomson during his 1847 expedition noted three forms of alluvia in the Spiti valley. The first is deposits of fine clay. The second is triangular platforms that slope gently from the mountains to the river, usually ending in a steep cliff. The third are enormous masses of great depth, 120–180 m (400–600 ft) above the river bed. The river has cut deep gorges through these platforms. The latter two consist of clay, pebbles and boulders. Thomson speculated that the valley appeared to have been a lake bed in the past though he could not conceive mechanisms to explain the phenomena.[13] Now, we know that the valley was uplifted from the ocean bed due to the movement of tectonic plates.[11]

The Moravian geologist Ferdinand Stoliczka discovered a major geological formation near Mud village in Spiti in the 1860s. Stoliczka identified a number of layers or successions, one of which he named as the Muth succession.[14] This was later renamed as the Muth System by Hayden (1908) and as the Muth Formation by Srikantia (1981).[15]

Climate

Spiti valley is arid as it is situated in the monsoon rain shadow of the Himalayas. The average annual rainfall is about 50 mm (2.0 in) with snowfall less than 200 cm (6.6 ft). Sporadically, there may be up to 15 mm (0.59 in) rainfall in a day resulting in erosion and landslides. The extreme temperatures are −25 °C (−13 °F) in winter and 15 °C (59 °F) in summer.[11]

Climate change

Villagers in Spiti, especially those in higher villages like Komik, Kibber, Lhangza etc., claim that in recent decades, glaciers have been melting faster, and the quantity of snowfall has decreased. Villages in Spiti are dependent entirely on snowmelt water from winter snows and glaciers. Lesser snow and faster-melting glaciers endangers agriculture in the valley, which anyhow has only one agricultural season, being a high-altitude cold desert.[16] Climate change is threatening the tradition of Gaddi shepherds' annual migrations to Spiti with their herds of goat and sheep. It is degrading the quality of the pastures, and the ice bridges that Gaddis with their flocks could earlier use to cross rivers while bypassing villages are now disappearing.[17] Scientific studies back up the ground-level observations that climate change due to global warming has been adversely affecting the environment of the Spiti valley.[18][19]

Flora and fauna

Spiti is a high altitude cold desert located above the tree line, with only a few stunted willows and scattered trees in some villages. There are shrubs on the valley floor.[11]: 1968 [9]: 28 Despite this, Spiti boasts of more than 450 species of plants. These include Seabuckthorn, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Aconitum, ratanjot (Khamad), Ephedra, Artemisia and other herbs. The alpine pastures on the high plateaus of Spiti are home to a variety of small bushes and grasses including Rosa sericea, Hipopheae, and Lonicera among others.[20] In terms of wildlife, among other species, the Spiti region is home to the Siberian ibex (Capra ibex sibirica), the snow leopard (Panthera uncia),[21] the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), pika (Ochotana roylei), Himalayan wolf (Canis lupus laniger), and weasels (Mustela spp).[20] The avifauna of the region includes the lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus), Himalayan friffon (Gyps himalayensis), golden eagle (Aquia chryaetos), Chukar partridge (Alectronics chukor), Himalayan snowcock (Tetraogallus himalayensis), and a host of rosefinches (Corpodacus spp).[20] Spiti is home to two protected areas, the Pin Valley National Park and the Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary.

Administration

The total area of the Spiti valley is 7,828.9 km2 (3,022.8 sq mi) and the total population in 2011 was 17,104 persons. Administratively, most of Spiti valley falls under Lahaul and Spiti district with a small part coming under Kinnaur district.[22][23]: 44,83

Spiti sub-division, Lahaul and Spiti district

The upper Spiti valley and the lower valley up to Sumdo[24] form one of the two sub-divisions of the Lahaul and Spiti district of Himachal Pradesh, the other one being the Lahaul sub-division. The sub-divisional headquarters (capital) of the Spiti sub-division of the Lahaul and Spiti district is Kaza,[25] which is situated on the bank of the Spiti River at an elevation of about 3,650 m (11,980 ft). The district headquarters lies at Kyelang in the Lahaul valley. But the Spiti valley is separated from Lahaul valley by These two divisions of Lahaul and Spiti district are connected by NH-505 over the high Kunzum Pass, at 4,590 m (15,060 ft). However, the Spiti sub-division is cut off from the district headquarters for 5–6 months in winter and spring as this road is cut off due to heavy snow.[25]

The Spiti sub-division is spread over an area of 7,101.1 km2 (2,741.8 sq mi).[22] According to the 2011 Census, the population of the Spiti sub-division is 12,445 persons.[26]

Designated as one of the 'Tribal Areas' of Himachal Pradesh, Spiti is administered under the Single-Line Administration system, which facilitates direct communication between the Kaza administration and the higher levels of administration in Himachal Pradesh.[27] Electorally, Spiti is a part of the Lahaul and Spiti constituency for the state-level Vidhan Sabha, and of the Mandi constituency for the national-level Lok Sabha.

Hangrang sub-tehsil, Kinnaur district

The lower Spiti valley from the Sumdo bridge until the Spiti merges with the Sutlej river at Khab is called the Hangrang valley. This area forms the Hangrang sub-tehsil which is part of the Poo sub-division in Kinnaur district.[28]: 14 The Hangrang sub-tehsil covers an area of 727.8 km2 (281.0 sq mi) with a population of 4,659 persons. The sub-tehsil is approximately 100 km (62 mi) from the district headquarters at Reckong Peo.[23]: 44,83

Access

Spiti valley is accessible throughout the year via Kinnaur from Shimla on a difficult 412 km-long (256 mi) road. The Spiti subdivision of Lahaul and Spiti District starts at Sumdo (74 km (46 mi) from Kaza) which is quite near the India–China border. In summer Spiti can be reached via Manali through the Atal tunnel and Kunzum Pass. Kaza, the headquarters of the Spiti subdivision, is 201 km (125 mi) from Manali. The road joining Manali to Spiti is treacherous and in bad condition as compared to the Shimla to Spiti road. Due to the high altitude one is likely to feel altitude sickness in Spiti. The Shimla to Spiti route is advised for travelers coming from lower altitudes as it gives them enough time to get acclimatized to the high altitude. This is because the road runs parallel to the Sutlej river initially, climbing steadily to 2,550 m (8,370 ft) at the confluence of the Spiti and Satluj near Khab. From Khab, NH-505 runs along the Spiti River, climbing steeply up to Nako (elev. 3,620 m (11,880 ft)) before continuing to Kaza. NH-505 enters Lahaul at Kunzum La.

All foreign nationals require an inner line permit to visit the Spiti valley. Earlier, Indian citizens also needed an Inner Line permit to visit Spiti, but this was abolished in 1992.[29]

Society and culture

Religion

The local people of Spiti follow Tibetan Buddhism,[30] and its culture is similar to those of its neighbouring regions such as Tibet, Ladakh,[31] and the Hangrang valley of Kinnaur district. The Gelug, Nyingma, and Sakya schools of Tibetan Buddhism have a presence in the Spiti valley. Each of these schools has monasteries in Spiti.[32][33]

The Tabo, Key, and Dhankar monasteries of Spiti belong to the Gelug school. The Kungri monastery and nunneries in Mud village in the Pin valley belong to the Nyingma school. The Kaza and Komik monasteries belong to the Sakya School. In the recent decades, nunneries have been established at Kwang, Morang, Pangmo, and Kungri. The Pin Valley of Spiti is home to the few surviving Buchen Lamas of the Nyingma school.[34] After Taklung Setrung Rinpoche, the head of the Nyingma sect and a noted scholar of the Tibetan Tantric school died on 24 December 2015, a search was started for his successor. In November 2022, the Nyingma sect located a boy in Rangrik village, Spiti who they believed to be the reincarnation of the late Rinpoche. The four-year old boy, Nawang Tashi Rapten, was born on 16 April 2018. On 28 November 2022, his head was tonsured to induct him into his new position and he started his formal religious education.[35][36]

Every village in Spiti has a small temple, or 'Lhakhang'. A well-known Lakhang in Spiti is the 'Serkhang', or 'Golden Temple', at Lhalung village.[37]

Social organisation

Traditionally, in Spiti, the society consisted of a hierarchy, with the Nonos (local aristocracy) at the top, the Chhazang (agriculturalists, practitioners of Tibetan medicine, and astrologers) in the middle, and the 'pyi-pa' (the separate endogamous groups of the 'Zo' blacksmiths and the 'Beda' musicians) at the bottom. Each of these groups tended to marry only among others of their own status.[38] By custom, inheritance in Spiti has been through primogeniture, with the eldest son inheriting the estate. All younger sons would have to become monks. If the eldest son died, the younger brother would have to leave the monastery and become the husband to the widowed wife. This was a form of fraternal polyandry.[39] Similarly, among women, by custom, only the eldest daughter would marry in earlier times. In some cases, younger daughters would become nuns. In others, they would stay at home either with their parents or the eldest brother, and were valuable additional work hands. In many cases, they died spinsters.[40] Polyandry was prevalent until a few decades ago; its practice has almost disappeared now. Monogamy and nuclear families prevail nowadays.[41]

The entire local population of Spiti is categorised as a Scheduled Tribe by the Government of India.[27] Nautor land rules have made it possible for those people to resort to law to get land, who by custom could not inherit and own land, just as in the neighbouring district of Kinnaur.[42]

Traditional livelihoods

Agriculture in Spiti has traditionally revolved around the cultivation of barley, and some amount of black pea. In recent decades, these crops have been supplanted by green pea cultivation.[43] Animal husbandry, particularly in higher parts of Spiti, revolves around yaks. Pin valley is renowned for the rearing of the rare Chumurti horse breed.[44] Spiti is a summer home to many semi-nomadic Gaddi sheep and goat herders who bring their animals for grazing. They come to Spiti from neighbouring regions and sometimes from as far as 250 km (160 mi) away. They enter the valley during summer as the snow melts and leave just a few days before the first snowfall of the winter season.

Local festivals

Some significant local festivities in Spiti include the Guitor at Kyi Gonpa (July), Ladarcha fair (mid-August), Spiti Losar (around November), Thuckchu (winter solstice in December), Dachang (around February), and Sia Mentok (around February). All these festivals have been traditionally tied up with agricultural and seasonal shifts. The alcoholic beverages chhaang and arak are locally prepared and very popular, both in festivals and on various occasions like birth, marriage, the celebration of some success, and death.

In popular culture

- Spiti was first photographed in the 1860s by Samuel Bourne, an early pioneer of photography in the Himalayas.[45]

- Spiti was first filmed in 1933 by Eugenio Ghersi, a member of the Italian Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci's expedition to Spiti and Western Tibet. The narration of this 46 minute-long video is in Italian.[46]

- The climax episode of Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim, first published as a book in 1901, is set in the Spiti valley.

- Spiti valley was the location for the shooting of some scenes in the Bollywood movies Paap, Highway, and Kesari.

- The Tibetan language film Milarepa, a biographical adventure tale about one of the most famous Tibetan Buddhist masters, was partly shot at the Dhankar Gompa and some other sites in the Spiti valley.

- Lonely Planet listed Lahaul and Spiti district as a whole, with specific mentions of both Lahaul and Spiti regions, among the 'Top 10 regions' in the world that were considered the best for travel over 2018, in an article published online on October 23, 2017.[47]

- The National Geographic issue of July 2020 carried a long story on the snow leopards of Spiti, and the social, conservation, and tourism-related issues around them.[48]

Economy

Cash-crop agriculture (of the green pea and apples), employment in state departments and development projects, and tourism are the main sources of income in the Spiti valley. Road accessibility has been of central importance to all these livelihoods and developmental activities.[29]

Agriculture

Spiti supports only one crop/year, in the period May – September. An administrator in 1871 reported that yaks were used for ploughing and the main crops were a fine hexagonal wheat, peas, mustard and two kinds of barley. As the Spiti river has eroded channels well below the valley floor, crops are irrigated using long channels winding along the terrain, often for many miles, to bring water from streams.[9]: 30–31

A survey of 10 villages in Spiti, ranging from Losar and Kibber in the upper valley to Tabo and Lari in the lower valley, was conducted in 2007–2009 by agricultural scientists. It was found that up to 1980, the important five crops were black pea, potato, barley (hulless and covered) and wheat. By 1990, farmers had diversified to nine crops. One of the new crops, garden peas, covered about 27% of the surveyed area, increasing to 47% by 2000. Some of the main reasons for adoption of new crops included better road connectivity and transport to reach markets, declining demand for traditional crops, and availability of hybrid seeds and favourable micro-climatic niches. A few farmers near Kaza have introduced apples, though the success rate is low owing to the low temperatures.[43]

Road access has been noted as being vital to Spiti's cash crop economy, as the harvest is almost entirely sold in distant markets in the north Indian plains. Interruptions in road accces caused by landslides during the post-harvest season, which overlaps with the monsoon season, can adversely affect the pricing of Spiti's cash crop produce.[29]

Tourism

Spiti was opened to tourism in 1992. Since 2016, this region has witnessed a tourism boom. Over 2019, 64,700 Indian tourists and 3,612 foreign tourists visited Spiti via the Shimla route, while numbers were not available for the Manali route.[29]

Places in Spiti popular among tourists include the following:[49][50]

- Chicham Bridge

- Chandra Taal lake

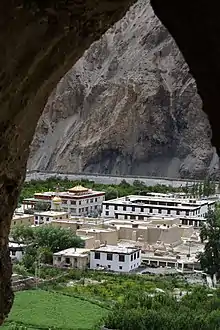

- Dhankar Lake and Dhankar monastery

- Gue monastery

- Hikkim village

- Demul village

- Kaza

- Key Monastery

- Kibber and Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary

- Komic village

- Kunzum Pass

- Langza village & Budhha statue

- Lhalung Monastery (Serkhang Monastery)

- Losar

- Mane Gogma and Mane Yogma villages

- Mud village

- Pin Valley National Park

- Tabo Caves and Tabo Monastery

Best time to visit Spiti Valley

The best time to visit Spiti Valley is May to October. During this summer season, Spiti is accessible from Manali and from Shimla. In winters the road from Manali is closed for almost 6 months due to heavy snowfall. Spiti is accessible during most of the winter from Shimla.[29] Besides tourists, many film-makers visit Spiti in winter for shooting.[51]

Sports

Spiti valley is an emerging destination for winter and ice sports, trekking and mountaineering, and adventure sports.[52]

Winter sports

Winter sports in Spiti include ice-skating, ice-hockey, skiing, and ice-climbing.

- In December 2019, an ice-skating and ice-hockey training camp was organised for the first time in Spiti, in Kaza.[53] In winter 2021–22, national ice-hockey and ice-skating championships were held in Kaza.[54]

- Skiing can also attempted during winters in Spiti.[55]

- In January 2019 and January 2020, ice-climbing festivals were organised in Spiti.[56][57]

Trekking

Some of the popular treks in Spiti include the following:

- The Kanamo peak is a popular 5,960 m (19,550 ft) high mountain above Kibber village, whose summit people can trek to.[58]

- The Parang La trek is a well-known trek for crossing from Spiti valley into Rupshu plains of Ladakh.[59][60]

- The Bhaba Pass trek in the Pin valley is a popular summer trek.[61]

- The Pin-Parvati pass trek, from Spiti into Kullu or the other way round, is considered a more challenging trek.[62]

- The trek from Reckong Peo in the Satluj valley to Nako in the Spiti valley climbs steeply to the Hango Pass, then descends to Leo (Liyo) on the south bank of the Spiti. The trail crosses the Spiti river and climbs up to Nako.[63]

Mountaineering

Spiti also has a number of peaks of interest to mountaineers.[64] Some of the significant peaks in Spiti include:

- The Gya peak - the highest peak in Spiti.[65]

- The Manirang peak

- The Shilla peak

- Mt Chocho Kang Nilda (CCKN)

- Reo Purgyil - the highest peak of Himachal Pradesh state; it lies in the Kinnaur district, but the Spiti River drains a part of its massif.

Bibliography

- Banach, Benti. (2010). A Village Called Self-Awareness, life and times in Spiti Valley. Vajra Publications, Kathmandu.

- Besch, Nils Florian (2006). Tibetan medicine off the roads: Modernizing the work of the Amchi in Spiti (Doctoral dissertation).

- Ciliberto, Jonathan. (2013). "Six Weeks in the Spiti Valley". Circle B Press. 2013. Atlanta. ISBN 978-0-9659336-6-7

- Francke, A. H. (1914, 1926). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Jahoda, Christian. (2015) Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture: Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna.

- Kapadia, Harish (1999). Spiti: Adventures in the Trans-Himalaya (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 81-7387-093-4.

- Mishra, Charudutt. (2001). High altitude survival: Conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife in the Trans-Himalayas. (Doctoral dissertation).

- Thukral, Kishore. (2006). Spiti: through Legend and Lore. Mosaic Books, New Delhi.

- Tobdan. (2015) Spiti: a Study in Socio-Cultural Traditions. Kaveri Books, New Delhi.

References

- "Losar - Chango, OpenStreetMap". OpenStreetMap. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Kapadia 1999, p. 209.

- A. S. Kashyap (2006). Dr. Satish K. Sharma (ed.). Horticulture in Cold Desert Conditions with Particular Reference to Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9788189422363. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Belleza, John Vincent (September 2017). "The Rock Art of Spiti. A General Introduction" (PDF). Revue d'Études Tibétaines. 41: 56–85. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Jahoda, Christian (2015). Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture. Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences. p. 37.

- Jahoda, Christian (2015). Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture. Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences. pp. 45–46.

- Kapadia 1999, Chapter 2.

- Jahoda, Christian (2015). Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture. Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. p. 62.

- Harcourt, A.F.P. (1871). The Himalayan Districts of Kooloo, Lahoul and Spiti. London: W.H. Allen & Sons.

- "District Lahaul and Spiti: History". Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- Srivastava, P.; Ray, Y.; Phartiyal, B.; Sharma, A. (1 March 2013). "Late Pleistocene-Holocene morphosedimentary architecture, Spiti River, arid higher Himalaya". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 102 (7): 1967–1984. Bibcode:2013IJEaS.102.1967S. doi:10.1007/s00531-013-0871-y. S2CID 129143186. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- "Khab, Himachal, OpenStreetMap.org". OpenStreetMap.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Thomson, Thomas (1852). Western Himalayas and Tibet. London: Reeve and Co. pp. 27, 123–124.

- Stoliczka, F. (1866). "Geological Sections across the Himalayan Mountains from Wangtu Bridge on the River Sutlej to Sungdo on the Indus, with an account of the formations in Spiti, accompanied by a revision of all known fossils from that district". Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. Geological Survey of India. V: 1–154.

- Parcha, S.K.; Pandey, Shivani (September 2011). "Devonian Ichnofossils from the Farakah Muth Section of the Pin Valley, Spiti Himalaya". Journal Geological Society of India. Bangalore: Geological Society of India. 78 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1007/s12594-011-0082-8. S2CID 129814827.

- "Climate change in Spiti: Water crisis engulfs world's 'highest' village". The Indian Express. 15 November 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Lenin, Janaki. "How Climate Change is Affecting an Old Pastoral Tradition in Spiti". The Wire. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Impact of Climate Change on Flora of Spiti Valley, SAC (2016), Monitoring Snow and Glaciers of Himalayan Region, Space Applications Centre, ISRO, Ahmedabad, India". Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Sangomla, Akshit; Sajwan, Raju. "On thin ice: Less snow, high temperatures have upturned lives in Himalayan cold desert". www.downtoearth.org.in. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Ecosphere Spiti Eco-Livelihoods". www.spitiecosphere.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- "Raacho Trekkers". Raacho Trekkers. 2 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- "Geographical Area | District Lahaul and Spiti, Government of Himachal Pradesh | India". Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- District Census Handbook: Kinnaur, Himachal -- Village and Town Directory. 3 Part XII A. Directorate of Census Operations, Himachal Pradesh, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- "Sumdo". OpenStreetMap. 18 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- "Himachal Tourism - Lahaul & Spiti District". Department of Tourism & Civil Aviation, Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- "Population | District Lahaul and Spiti, Government of Himachal Pradesh | India". Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "Draft Annual Tribal Sub-Plan 2018-19" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- District Census Handbook: Kinnaur, Himachal -- Village and Town wise Primary Census Abstract (PCA). 3 Part XII B. Directorate of Census Operations, Himachal Pradesh, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Pandey, Abhimanyu (2023). "Fragile mountains, extreme winters, and bordering China: Interrogating the shaping of remoteness and connectivity through roads in a Himalayan borderland". Aktuelle Forschungsbeiträge zu Südasien - 12. Jahrestagung des AK Südasien, 21./22. Januar 2022, Bonn/online (PDF). Heidelberg: Heidelberg Asian Studies Publishing. pp. 14–17.

- V. Verma (1997). Spiti: A Buddhist Land in Western Himalaya. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 67. ISBN 9788170189718.

- Permanent Delegation of India to UNESCO (15 April 2015). "Cold Desert Cultural Landscape of India". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Thukral, Kishore (2006). Spiti through Legend and Lore. New Delhi: Mosaic Books.

- "Monasteries in Spiti | District Lahaul and Spiti, Government of Himachal Pradesh | India". Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Sutherland, P.; Tsering, Tashi (2011). Disciples of a Crazy Saint: The Buchen of Spiti. Pitt Rivers Museum.

- Bhattacherjee, K. (24 November 2022). "Buddhist Nyingma sect finds 'reincarnation' of famous Rinpoche". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- Bisht, G. (28 November 2022). "Nyingma monks find reincarnation of Buddhist master in 4-year-old Spiti boy". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- Tropper, Kurt (2008). The founding inscription in the gSer khaṅ of Lalung (Spiti, Himachal Pradesh): edition and annoted translation. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

- Jahoda, Christian (2015). Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture: Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 169–174.

- Tobdan (2015). Spiti: a Study in Socio-Cultural Relations. New Delhi: Kaveria Publishers. pp. 29–30.

- Tobdan (2015). Spiti: a Study in Socio-Cultural Traditions. New Delhi: Kaveri Books. pp. 36–37.

- Jahoda, Christian (2015). Socio-economic organisation in a border area of Tibetan culture: Tabo, Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. p. 178.

- Rahimzadeh, Aghaghia (1 January 2018). "Political ecology of land reforms in Kinnaur: Implications and a historical overview". Land Use Policy. 70: 570–579. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.025. ISSN 0264-8377.

- Sharma, H.R.; Chauhan, S.K. (2013). "Agricultural Transformation in Trans Himalayan Region of Himachal Pradesh: Cropping Pattern, Technology Adoption and Emerging Challenges". Agricultural Economics Research Review. 26 (Conference): 173–179. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- Lenin, Janaki (17 October 2016). "How Climate Change is Affecting an Old Pastoral Tradition in Spiti – The Wire Science". Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Samuel Bourne's Himalaya". www.outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Nel Tibet occidentale - Primo, secondo e terzo tempo". Archivio Storico Luce (in Italian). Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "Best in Travel 2018: top 10 regions". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Himalaya snow leopards are finally coming into view". National Geographic Magazine. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Places to Visit in Spiti Valley | Welcome to the Heaven!". Being Himalayan. 3 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Spiti Valley Circuit Tour". Raacho Trekkers. 21 April 2022. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Sharma, Ashwani (3 December 2021). "Himachal Wakes Up To Blanket Of Snow In Lahaul-Spiti, Winter Rain Freezes Shimla". Outlook (Indian magazine). Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Deepak Sanan; Dhanu Swadi (2002). Exploring Kinnaur in the Trans-Himalaya. Indus Publishing. p. 276. ISBN 9788173871313. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- Service, Tribune News. "Ice hockey training camp begins at Kaza". Tribuneindia News Service. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- Bisht, Gaurav (16 July 2022). "Himachal govt sets up highest gym at Kaza in Spiti valley". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- HT Correspondent, Dharamsala (29 March 2022). "Lahaul-Spiti to host its maiden skiing and snowboard championship". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- "Piti Dharr – International Ice Climbing Festival in the Himalayas". Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Townscript | Online Event Registration and Ticketing Platform". www.townscript.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Sharma, Dheeraj (14 September 2020). "Kanamo Peak Trek in Spiti Valley - A Travel Guide Covering Everything". Devil On Wheels™. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Raacho Trekkers". Raacho Trekkers. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- "Spiti Holiday Adventure". Spiti Holiday Adventure. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Pin Bhaba Pass Trek". indiahikes.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- "Pin Parvati Pass". indiahikes.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- Government of Himachal Pradesh (24 January 2023). "Kinnaur: Adventures: Reckong Peo to Nako".

- Kapadia 1999, p. 9.

- "The HJ/55/12 THE CONTINUING STORY OF GYA". The HJ/55/12 THE CONTINUING STORY OF GYA. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- Paul, Abhirup (8 June 2020). "Cycling in Spiti Valley - Experience of a Lifetime". Vargis Khan. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- "Spiti Half Marathon". World's Marathons. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- "Spiti Valley Road is one of the toughest roads left on this planet". www.dangerousroads.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Sharma, Dheeraj (18 February 2013). "Spiti Valley Most Common Itinerary - Detailed Travel Plan for Travellers". Devil On Wheels™. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.