Sportswashing

Sportswashing is a term used to describe the practice of individuals, groups, corporations, or governments using sports to improve reputations tarnished by wrongdoing. A form of propaganda, sportswashing can be accomplished through hosting sporting events, purchasing, or sponsoring sporting teams, or participating in a sport.[1]

At the international level, it is believed that sportswashing has been used to direct attention away from poor human rights records and corruption scandals.[2] At the individual and corporate levels, it is believed that sportswashing has been used to cover up vices, crimes, and scandals. Sportswashing is an example of reputation laundering.

Overview

Internationally, sportswashing has been described as part of a country's soft power.[3][4][5][6] The first usage of the term "sportswashing" may have been applied to Azerbaijan and its hosting of the 2015 European Games in Baku.[7]

People from countries accused of sportswashing often argue that they simply want to enjoy sporting events in their home countries and that sporting boycotts and event relocation are both unfair to sporting fans and are ineffective in changing government policy.[8] The 2018 FIFA World Cup held in Russia has been cited as an example to tackle the country's global reputation, which was low due to its foreign policy and the sporting event changed the focus of discussions to the success of the World Cup.[9]

Companies have also been accused of sportswashing include Ineos' sponsorship of professional cycling's Team Sky (now the Ineos Grenadiers) in 2019,[10] and Arabtec's sponsorship of Manchester City F.C.[11]

Sportswashing is often very costly. For example, in March 2021, human rights organization Grant Liberty said that Saudi Arabia alone has spent at least $1.5 billion on alleged sportswashing activities.[12][13]

Hosting

Basketball

- The 1978 FIBA World Championship, held in the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos.[14]

- The 2013 FIBA Americas Championship, held in Venezuela.[15]

- The 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup, held in China.[16][17]

- The 2021 BAL season, held in Rwanda.[15]

- The 2023 FIBA Basketball World Cup, held partially in the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos' son Bongbong.[18]

- The 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup, held in Qatar[19]

Boxing

- The 1973 light heavyweight boxing match between South African Pierre Fourie and American Bob Foster, held in Rand Stadium, Johannesburg, South Africa during the apartheid era.[20]

- The 1974 undisputed world heavyweight title match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, known as The Rumble in the Jungle, held in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo).[21]

- The 1975 world heavyweight title trilogy match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, known as Thrilla in Manila, held in Quezon City, Philippines during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.[21]

- The 1980 WBA World Heavyweight Championship match between Gerrie Coetzee and Mike Weaver, held in Sun City, South Africa during the apartheid era.

- The 2015 AIBA World Boxing Championships held in Qatar.[22]

- The 2019 world heavyweight title rematch between Andy Ruiz Jr. and Anthony Joshua, known as Clash on The Dunes, held in Diriyah, Saudi Arabia.[21][23]

- The 2022 world heavyweight title rematch between Oleksandr Usyk and Anthony Joshua known as Rage on the Red Sea, held in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Cycling

- Vuelta a Venezuela.[15]

- Vuelta a Cuba held in 1964–2010.[24]

- Vuelta al Táchira.[15]

- Tour of Qatar held in 2002–2016.[25]

- Tour of Beijing held in 2011–2014.[25]

- Dubai Tour held in 2014–2018.[25]

- Abu Dhabi Tour held in 2015–2018.[25]

- 2016 UCI Road World Championships held in Qatar.[22]

- Tour of Guangxi held since 2017.[25]

- Second stage of 2018 Giro d'Italia held in Israel.[24][26]

- UAE Tour held since 2019[25]

- Tour Femenino de Venezuela held in 2019.[15]

- Tour of Oman held since 2020.[25]

- The 2025 UCI Road World Championships scheduled to be held in Rwanda.[27]

Cricket

- The 1996 Cricket World Cup held in Sri Lanka.[28]

- The 2003 Cricket World Cup held in Zimbabwe.[29][30]

Football tournaments

- The 1934 FIFA World Cup held during the rule of Benito Mussolini in Italy.[31]

- The 1964 European Nations' Cup held in Spain under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.[32]

- The 1972 AFC Asian Cup held in Thailand under a military dictatorship.

- The 1978 FIFA World Cup held in Argentina under a military dictatorship.[33]

- The 1985 FIFA World Youth Championship held in the Soviet Union.

- The 1985 FIFA U-16 World Championship held in China.

- The 1987 FIFA World Youth Championship held in Chile under a military dictatorship.

- The 1988 AFC Asian Cup held in Qatar.[22]

- The 1989 FIFA World Youth Championship held in Saudi Arabia.

- The 1991 FIFA Women's World Cup held in China.

- The 1995 FIFA World Youth Championship held in Qatar.[22]

- The 2002 Supercoppa Italiana between Juventus and Parma held in Libya under Muammar Gaddafi.[34]

- The 2004 AFC Asian Cup held in China.

- The 2007 FIFA Women's World Cup held in China (initially awarded the 2003 bid but moved to the United States due to SARS).[17]

- The 2007 Copa América held in Venezuela.[35]

- The 2009 FIFA Club World Cup and 2010 FIFA Club World Cup were both held in the United Arab Emirates.

- The 2011 AFC Asian Cup held in Qatar.[22]

- The 2013 Trophée des Champions between Paris Saint-Germain and Bordeaux held in Gabon.[36]

- The 2014 FIFA World Cup held in Brazil.[37]

- The 2017 FIFA Club World Cup and 2018 FIFA Club World Cup were both held in the United Arab Emirates.

- The 2018 FIFA World Cup held in Russia.[38]

- The Supercoppa Italiana held two controversial football matches in Saudi Arabia:

- The 2018 Supercoppa Italiana between Juventus and AC Milan held in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[39]

- The 2019 Supercoppa Italiana between Juventus and S.S. Lazio held in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[24]

- The 2019 AFC Asian Cup to be held in the United Arab Emirates.

- The 2019 UEFA Europa League Final between Chelsea and Arsenal held in Azerbaijan[40]

- The 2019 FIFA Club World Cup and the 2020 FIFA Club World Cup were both held in Qatar.[22]

- The Supercopa de España held football matches in Saudi Arabia:

- 2019–2020 Supercopa de España held in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[41][42]

- 2021–2022 Supercopa de España held in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.[41][43]

- 2022–2023 Supercopa de España held in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[44]

- The Euro 2020 held in various countries, including the countries with poor human rights record:

- Group F and round of 16 held in Budapest, Hungary[45]

- Group A and quarter-finals held in Baku, Azerbaijan[46]

- Group B, Group E and quarter-finals held in Saint Petersburg, Russia

- The 2021 Copa América held in Brazil.[47]

- The 2021 Diego Maradona tribute match between FC Barcelona and Boca Juniors dubbed as "Maradona Cup" held in Saudi Arabia.[48]

- The 2021 Trophée des Champions between Lille and Paris Saint-Germain in Israel.[49]

- The 2021 Africa Cup of Nations held in Cameroon.[50]

- The 2021 FIFA Club World Cup held in the United Arab Emirates.

- The 2022 Trophée des Champions between Paris Saint-Germain and Nantes also held in the same place as last season.[51][52]

- The 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.[22][53]

- The 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup; Saudi Arabia tried to be the sponsor, but after some outrage, it pulled out. [54]

- The 2023 AFC Asian Cup to be held in Qatar (originally in China)[55]

- The 2023 FIFA Club World Cup to be held in Saudi Arabia[56]

- The 2027 AFC Asian Cup to be held in Saudi Arabia[57]

Esports

- The 2019 BLAST Pro Series Finals held in the Kingdom of Bahrain.[58]

- Danish esports organization, RFRSH Entertainment and Riot Games both signing a deal to develop Saudi Arabia's NEOM project and boost esports in the region.[59] Riot ended up scrapping the partnership after facing intense backlash from fans and their employees.[60][61]

- The 2022 Blast Premier World Final held in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.[62]

Golf

- Venezuela Open held since 1957.

- Brunei Open held since 2005.

- PGA Tour China held since 2014.[63]

- China Tour held in 2014–2019.[63]

- Saudi International held since 2019.[64]

- Aramco Team Series held since 2020.[64]

- Aramco Saudi Ladies International held since 2020.[64]

- LIV Golf Invitational Series funded by Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund, beginning in 2022.[65][66]

Formula One

- Spanish Grand Prix held from 1951 to 1975[67]

- Argentine Grand Prix held from 1953 to 1981[68]

- Portuguese Grand Prix held from 1958 to 1960[69]

- South African Grand Prix held from 1960 to 1985[70][71]

- Mexican Grand Prix held since 1962[72]

- Brazilian Grand Prix held from 1972 to 1984[73]

- Hungarian Grand Prix held since 1986

- Malaysian Grand Prix held from 1999 to 2017[72]

- Bahrain Grand Prix held since 2004[74][75]

- Chinese Grand Prix held since 2004[72]

- Abu Dhabi Grand Prix held since 2009[75]

- Russian Grand Prix held from 2014 to 2021[72]

- 2016 European Grand Prix held in Baku, Azerbaijan[24]

- Azerbaijan Grand Prix held since 2017[76][67]

- Turkish Grand Prix held in 2020 and 2021[72]

- Qatar Grand Prix held since 2021[72][75]

- Saudi Arabian Grand Prix held since 2021[72][75]

Formula E

- Beijing ePrix held in 2014–2015.[72]

- Putrajaya ePrix held in 2014–2015.[72]

- Moscow ePrix held in 2015.[72]

- Diriyah ePrix held since 2018.[77]

- Sanya ePrix held in 2019.[72]

- Jakarta ePrix held since 2022.[78]

Grand Prix motorcycle racing

- East German motorcycle Grand Prix held in 1958–1972.

- Argentine motorcycle Grand Prix held in 1981–1982.[68]

- South African motorcycle Grand Prix held in 1983–1985.[70][79]

- Malaysian motorcycle Grand Prix held since 1991.[72]

- Indonesian motorcycle Grand Prix held in 1996–1997 and since 2022.[78][80]

- Qatar motorcycle Grand Prix held since 2004.[81][22]

- Chinese motorcycle Grand Prix held from 2005 to 2008.

- Thailand motorcycle Grand Prix held since 2018.[81]

Rally

- Rally Indonesia held between 1996 and 1997 respectively.

- Rally China held in 1999 season only.

- Rally of Turkey held from 2003 until 2006, then in 2008 and 2010, and then again from 2018 until 2020.

- Jordan Rally held in 2008, 2010 and 2011.

- The Dakar Rally held in Saudi Arabia since 2020.[82]

Sportscar racing

- 1988 World Sportscar Championship at Brno Czechoslovakia under the Communist dictatorship

- 8 Hours of Bahrain held since 2012

- 4 Hours of Shanghai, held in 2012-2019

- Qatar 1812 km scheduled to be held in 2024

Touring car racing

- ETCC/WTCC at Brno Czechoslovakia 1976-1987 when Czechoslovakia was under a Soviet backed Communist dictatorship.

- FIA WTCR Race of Bahrain held in 2022. [83]

- FIA WTCR Race of Saudi Arabia held in 2022.[83]

Olympic Games

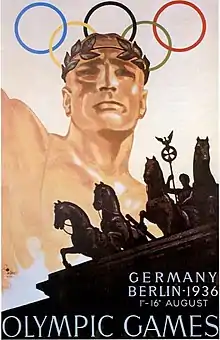

- The 1936 Winter Olympics held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Nazi Germany.

- The 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Nazi Germany.

- The 1968 Summer Olympics held in Mexico City, Mexico.

- The 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union.[84][85]

- The 1988 Summer Olympics held in military-led Seoul, South Korea.[86][87]

- The 2008 Summer Olympics held in Beijing, China.[88]

- The 2014 Winter Olympics held in Sochi, Russia.[89][90]

- The 2016 Summer Olympics held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[91]

- The 2022 Winter Olympics held in Beijing, China.[88][92][93]

Rugby Union

Rugby Union tours involving South Africa during the Apartheid era:[70]

- The 1949, 1960, 1970, 1976 New Zealand tours to South Africa

- The 1951–1952, 1960–1961, 1965, 1969–1970 South African tours to Britain and Ireland

- The 1952, 1961, 1968, 1974 South Africa tours to France

- The 1953, 1961, 1963, 1969 Australia tours to South Africa

- The 1955, 1962, 1968, 1974, 1980 British & Irish Lions tours to South Africa

- The 1956, 1965, 1971 South Africa tours to Australia

- The 1956, 1965, 1981 South Africa tours to New Zealand

- The 1958, 1964, 1967, 1971, 1975, 1980 France tours to South Africa

- The 1960 Scotland tour to South Africa

- The 1964 Wales tour to South Africa

- The 1965, 1971 Argentina tours to South Africa both with tests against the South African Gazelles

- The 1972, 1984 England tours to South Africa

- The 1973 Italy tour to South Africa

- The 1980 South African tour to South America

- The 1980, 1982 and 1984 South American Jaguars tours to South Africa

- The 1981 Ireland tour to South Africa

- The unofficial 1986 New Zealand tour to South Africa

During communist rule, Romania undertook several Rugby Union tours:

- The 1973 Romania tour to Argentina

- The 1975 Romania tour to New Zealand

- The 1979 Romania tour to Wales

- The 1980 Romania tour to Ireland

- The 1981 Romania tour to Scotland

- The 1984–1985 Romania tour to England

During military rule in Fiji, the country's Rugby Union team went on numerous overseas tours:

- The 1989 Fiji tour to Europe

- The 1989 Fiji tour to Oceania

- The 1990 Fiji tour to Hong Kong and France

- The 1995 Fiji tour to Wales and Ireland

- The 1996 Fiji tour to Hong Kong

- The 1996 Fiji tour to New Zealand and South Africa

- The 1997 Fiji tour to New Zealand

During the 1976–1983 military dictatorship in Argentina, seven countries played against Argentina's Rugby Union team: New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, Wales, England, Italy and France.

- The 1976 Argentina tour to Wales with one provincial match in England v North & Midlands

- The 1976 New Zealand tour to Argentina with a match against Uruguay

- The 1977 France tour to Argentina

- The 1978 Argentina tour to England with a match in Wales a unofficial test against Wales B a provincial match in Ireland v Leinster and a test match in Italy

- The 1979 Argentina tour to New Zealand

- The 1979 Australia tour to Argentina

- The 1980 Fiji tour to Argentina

- The 1981 England tour to Argentina

- The 1982 Argentina tour to France and Spain

- The 1983 Argentina tour to Australia

Snooker

These are Snooker tournaments held in China under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party

Tennis

- South Africa Open during the apartheid period (1948-1994).[20]

- 1972 Federation Cup held in apartheid South Africa.[20]

- 1974 Davis Cup held in apartheid South Africa.[20]

- St. Petersburg Open held since 1993.

- Dubai Tennis Championships held since 1993.[94]

- ATP Qatar Open held since 1993.[22]

- WTA Qatar Open held since 2001.[22]

- China Open held since 2004.[95]

- Wuhan Open held since 2014.[95]

- 2017 Fed Cup held in Belarus

- Diriyah Tennis Cup held since 2019.[77]

Wrestling

- Collision in Korea held in Pyongyang, North Korea in 1995.[96]

- WWE in Saudi Arabia held in Saudi Arabia since 2014.[97]

- WWE Crown Jewel held in Saudi Arabia since 2018.[97]

Other events

_01.jpg.webp)

- Some of UFC matches are held in China, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates.[98]

- Proposed NFL games in China, including the China Bowl.[99]

- The 1979 Southeast Asian Games held in Indonesia under the dictatorship of Suharto.

- The 1981 Southeast Asian Games held in The Philippines under the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.

- The 1986 Commonwealth Games held in Scotland.[100]

- The 1987 Southeast Asian Games held in Indonesia under the dictatorship of Suharto.

- The 1991 Pan American Games held in Cuba.[24]

- The 1997 Southeast Asian Games held in Indonesia under the dictatorship of Suharto.

- The 1998 Commonwealth Games held in Malaysia.

- The 2006 Asian Games held in Qatar.[22]

- The 2014 Men's Ice Hockey World Championships held in Belarus.[101]

- The 2015 European Games held in Azerbaijan.[40]

- The 2017 Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games held in Turkmenistan.[24]

- The Women's World Chess Championship 2017 held in Iran.[102]

- The 2019 Winter Universiade held in Russia.[24]

- The 2019 European Games held in Belarus.[103]

- The 2019 Military World Games held in China.[104]

- The 2019 Southeast Asian Games held in The Philippines.[105]

- The 2021 Summer World University Games scheduled to be held in China after a 2-year delay from its original dates.[17]

- The World Chess Championship 2021 held in the United Arab Emirates.[106]

- The 2022 Gay Games scheduled to be held in Hong Kong.[107][108]

- The 2022 World Aquatics Championships held in Budapest.[109]

- The 2023 World Athletics Championships held in Budapest.

- The 2022 Asian Games scheduled to be held in China.[17]

- The 2023 Jeux de la Francophonie scheduled to be held in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- The 2030 Asian Games scheduled to be held in Qatar.[110]

- The 2034 Asian Games scheduled to be held in Saudi Arabia.[110]

Corporate sponsorship

Association football

- Russian state-owned oil company Gazprom's sponsorship of the German Bundesliga football team Schalke 04, events of the UEFA Champions League and kits. This contract was cancelled due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[111][112][113]

- Russian holding company USM Holdings Limited's sponsorship of Everton. The company is owned by Alisher Usmanov, a pro-Kremlin businessman.[114]

- Russian flag carrier Aeroflot's sponsorship of Manchester United. The sponsorship was ended following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[115]

- Qatar Airways' sponsorships of football teams, including FC Barcelona, A.S. Roma, Boca Juniors, Paris Saint-Germain, and Bayern Munich.[116]

- Qatar's Hamad International Airport's sponsorship of Bayern Munich from 2018 to 2023.[117][118][119]

- Bahrain's flag carrier Gulf Air's sponsorships of Chelsea and Queens Park Rangers.[70]

- The Azerbaijan tourism authority's sponsorship of Atlético Madrid.[120]

- Hong Kong-based insurance company AIA Group sponsorship of English football club Tottenham Hotspur. AIA Group endorsed the Hong Kong national security law in 2020, which was condemned by several British politicians who demanded the club to drop the sponsorship.[121]

- The Rwanda tourism authority's sponsorship of Arsenal and Paris Saint-Germain.[15]

- The Saudi Tourism Authority's sponsorship of the 2022 FIFA Club World Cup under the Visit Saudi branding.

Australian rules football

- Brunei's flag carrier Royal Brunei Airlines' sponsorship deal with AFL Europe in 2014. The sponsorship deal ended the same year after protests from rights groups.[122][123]

Cycling

- Shell oil company's major partnership with British Cycling in 2022.[124]

Golf

- The Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, Public Investment Fund sponsored the LIV Golf in 2021. Human rights organizations criticized Saudi Arabia for sportwashing its image through the tournament. Human Rights Watch also wrote a letter to LIV Golf urging the league to adopt a strategy that would minimize the risk of reputation laundering by the Saudi Arabian government.[125]

Motorsport

- Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA's sponsorship of Formula One driver Pastor Maldonado, who raced for Williams Grand Prix Engineering in 2011–2013 and Lotus F1 in 2014–2015. The PDVSA logo was included on both teams' car decals during those periods.[126]

- Citgo, oil company owned by Venezuelan PDVSA sponsorship of numerous NASCAR teams such as Wood Brothers Racing and Roush Racing. Citgo also sponsored individual drivers such as Milka Duno who raced in 24 Hours of Daytona and E. J. Viso who raced in IndyCar Series[127][128]

- Chinese state-owned broadcaster CCTV's sponsorship of Jordan Grand Prix Formula One team in 2003.[129]

- Saudi Arabia State-owned oil company Aramco's sponsorship of the Aston Martin F1 Team, as well as Formula One races.[130][131][81]

- Saudi Arabian flag carrier Saudia's sponsorship of Formula One teams Williams Grand Prix Engineering from 1977 to 1984 and Aston Martin in 2023.[132]

- The Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund-backed Neom sponsorship of the Mercedes-EQ Formula E Team and McLaren's Formula E and Extreme E teams.[133][134]

- The Formula One team Haas F1 Team was sponsored by Uralkali, who also sponsors Haas' Russian driver Nikita Mazepin. Haas had severed ties with Uralkali and Mazepin due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[135]

Ownership

Association football

Domestic teams:

- Italian media proprietor Silvio Berlusconi, through his Fininvest holding, owned Serie A club A.C. Milan in 1986 and had 98% of the club's share until 2017. Berlusconi gained popularity in the country using his team's success, strongly supported by his own mass media including Mediaset, to improve public opinion,[136] which was useful for his political purposes.[137] Berlusconi founded Forza Italia, a centre-right party, and in 1994 became Prime Minister of Italy. During more than two decades of government divided into four periods, he was involved in abuse of office, bribery, corruption of public personnel, and false accounting cases, as well as sex scandals,[137] among other controversies surrounding Berlusconi. He proposed and approved many ad personam laws (a type of clientelism) in favour of his own business, including the Milanese club as the Lentini affair in 1995, the Decreto Salva Calcio in 2003,[138][139] which allowed Milan to be relieved its debt of € 242 million,[140][141] and the decriminalisation of false accounting during the second Berlusconi government, a charge for which his club and local rival FC Internazionale Milano were tried and acquitted five years later due that measure;[140][142] obtaining political support from the Milan fanbase, one of the largest in the country.[143] In 2018, after he sold Milan to Chinese businessman Li Yonghong, Berlusconi, through Fininvest, owned AC Monza, a club that then competed in the national Serie C, with 100% of the club's shares.

Foreign ownership:

- Russian politician and businessman Roman Abramovich's ownership of Chelsea F.C. (2003–2022), which some have reported was done at the request of Russian President Vladimir Putin.[144]

- Russian pro-Kremlin businessman Alisher Usmanov formally owned partial shares of Arsenal F.C.[114][145]

- Abu Dhabi majority ownership of City Football Group. In 2015, the Abu Dhabi United Group announced consortium with Chinese state-owned CITIC Group for City Football Group, an entity which in turn owns[146]

- Manchester City F.C. (since 2008)

- Melbourne City FC

- Montevideo City Torque

- New York City FC,

- Yokohama F. Marinos,

- Girona FC,

- Sichuan Jiuniu F.C. (partially).

- Mumbai City FC (partially).

- Saudi prince Abdullah bin Musaid Al Saud ownership of Sheffield United.[147]

- The purchase of Newcastle United F.C., 80% financing provided by Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund; this was "a blatant example of Saudi sportswashing", according to Kate Allen of Amnesty International UK.[148]

- Kingdom of Bahrain 20% stake purchase of French football club Paris FC. The purchase was condemned by French-based human rights NGOs.[149]

- Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, ruler of Qatar, purchasing French football club Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) in 2011.[150]

- Controversial Indonesian conglomerate Bakrie Group ownership of Australian football club Brisbane Roar FC. In 2019, formed team administrator Joko Driyono was arrested by the Indonesian national police for destroying the evidence of match-fixing scandal.[151]

- Washington Spirit's 2020 cultural exchange with Qatar.[152]

Basketball

- Russian businessman Mikhail Prokhorov ownership of NBA team Brooklyn Nets. Prokhorov was known to be a close ally to Russian President Vladimir Putin. In 2017, Prokhorov sold the team which was alleged to have been a request from Putin.[153] The team was later bought by Hong Kong businessman Joe Tsai. Tsai was previously criticized for his praise of China's restrictions on personal freedoms and expressing his support of Hong Kong national security law.[154]

Cricket

- Indian fugitive businessman Vijay Mallya ownership of cricket team Royal Challengers Bangalore who competed in Indian Premier League. Indian Enforcement Directorate accused Mallya ownership of the team to be part of Mallya's money laundering scheme.[155]

- The South Africa national cricket team held numerous tours dubbed as South African rebel tours around 1982-1990, defying sporting bodies' sanctions of numerous South African sport teams for participating in international sporting events. The tours have been regarded as part of the apartheid government's sporting propaganda.[156][157]

Cycling

- There are numerous reports that 2020 Tour de France was used by problematic countries and companies to sportswash their tarnished reputation; the following teams have been accused of sportswashing during the event:[158][159]

Motorsport

- Indian fugitive businessman Vijay Mallya's ownership of the Force India Formula One team. Mallya's Force India team were accused by the Indian Enforcement Directorate that it was created for money laundering purposes.[155]

- Kingdom of Bahrain state-owned sovereign wealth fund, Mumtalakat Holding Company, partial stake at McLaren Group which includes its racing division, McLaren Racing, which competes in Formula One, Formula E, Extreme E and IndyCar Series.[160]

Other

- The Al Maktoum family's ownership of Godolphin and Essential Quality.[161]

- The takeover of esports organizations ESL and FACEIT by Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund.[162]

By individuals

- Daniel Kinahan's involvement in boxing as a promoter.[163]

- Brother of Venezuelan PSUV politician and Bolibourgeoisie Jesse Chacón, Arné Chacón ownership of stable in Florida called Gadu Racing Stable Corp and participation of horse racing in United States.[164]

- Chechnya leader Ramzan Kadyrov ownership of horse Mourilyan which competed in Melbourne Cup horse racing. The participation has gained controversy in Australia. Australian Senator Bob Brown called the Australian government to quarantine the prize money as concern of money laundering.[165] and having runners in various meetings in the UK especially Royal Ascot

- International Cycling Union presenting a certificate of appreciation to Turkmen dictator Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow for "in development of sport and consolidation of universal peace and progress".[166]

See also

References

- "What is sportswashing and why is it such a big problem?". Greenpeace UK. 23 March 2023. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- Wilson, Jonathan. "Sportswashing and Global Football's Immense Power". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "Sportswashing, a new word for an old idea – Sportstar". 24 April 2020. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Saudi uses sports 'soft power' as lever of influence". France 24. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Qatar's soft power sports diplomacy". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Saudi uses sports 'soft power' as lever of influence". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "From the Qatar World Cup 2022 to F1, PSG, Newcastle Utd and Man City: 'Sportswashing' allegations explained". inews. 23 November 2021. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- "'Sportswashing': unethical but sadly here to stay". Palatinate. 24 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Sportswashing: a growing threat to sport". Upstart. 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "The 'Sportswashing' Behind One of the World's Biggest Cycling Teams". www.vice.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Amnesty criticises Manchester City over 'sportswashing'". The Guardian. 11 November 2018. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "Saudi Arabia has spent at least $1.5bn on 'sportswashing', report reveals". The Guardian. 28 March 2021. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "Saudi Arabia has spent 'at least' $1.5bn on 'sportswashing'". Middle East Monitor. 29 March 2021. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Ramirez, Bert A. "Looking back: The 1978 World Basketball Championship in Manila (Part I)". Rappler. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- "Igniting the Truth Against Authoritarian Sportswashing". Human Rights Foundation. 17 December 2021. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "世界盃》美國男籃再少一人 國王後衛福克斯也退出國家隊". 自由體育. 18 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Chu, Marcus P. (9 April 2021). Sporting Events in China as Economic Development, National Image, and Political Ambition. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030700164. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Mangaluz, Jean. "Bongbong Marcos reminisces father's Fiba ceremonial toss, vows support for World Cup". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- "Qatar announced as host of the FIBA Basketball World Cup 2027". FIBA.basketball. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- Sikes, Michelle M; Rider, Toby C.; Llewellyn, Matthew P. (29 November 2021). Sport and Apartheid South Africa: Histories of Politics, Power, and Protest. Routledge. ISBN 9781000488524.

- "What is it with heavyweight boxers and brutal dictators? | Opinion". Newsweek. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Søyland, Håvard Stamnes (November 2020). "Qatar's sports strategy: A case of sports diplomacy or sportswashing?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Sport and human rights – where should stars draw a line in the sand?". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Lenskyj, Helen Jefferson (15 April 2020). The Olympic Games: A Critical Approach. Emerald Publishing. ISBN 978-1838677763.

- Rogers, Neal (12 February 2019). "The Weekly Spin: The Intersection Of Pro Cycling And Basic Human Rights". CyclingTips. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Van Densen, Lars. "Hanging out the Laundry Sportswashing in Cycling". ProCyclingUK. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Harris, Joe; Maxwell, Steve (22 September 2021). "The Outer Line: The UCI approaches a sportswashing crossroads". VeloNews. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Why Australia and West Indies refused to play in Sri Lanka during 1996 World Cup?". Mykel. 28 June 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- "Standing up for their principles". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "The black band of courage". ESPN Cricinfo. 2 May 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "Sportswashing and the tangled web of Europe's biggest clubs". The Guardian. 15 February 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- "How Francisco Franco Utilised Spanish Football To Consolidate His Power". Pundit Arena. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Ellis, James (16 October 2020). "Sportswashing and Atrocity: The 1978 FIFA World Cup". Yet Again. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Billebault, Alexis (25 September 2020). "Libya: When Muammar Gaddafi played political football". The Africa Report. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Richards, Joel (16 July 2007). "How the vinotinto attempted to capture the mood of a nation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Brossier, Aurélien (3 August 2013). "Trophée des champions : pourquoi le Gabon ?" [Trophée des champions : why Gabon?] (in French). Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Bento, Luciana (11 April 2014). "Brazil: Human rights under threat ahead of the World Cup". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022.

- Glenday, James (13 June 2018). "World Cup dream is 'sportswashing' Russia's appalling record". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Supercoppa italiana: appelli a Juventus e Milan per boicottare la finale di Riad dopo l'assassinio di Khasshoggi" (in Italian). SuperNews. 26 October 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- "Amnesty: stop Azerbaijan from sportswashing 'appalling human rights record'". The Irish Times. 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Kohan, Marisa (15 November 2019). "Así es Arabia Saudí, el país que albergará la Supercopa y que viola derechos humanos" [This is Saudi Arabia, the country that will host Supercopa and a human rights violators]. www.publico.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Seb Stafford-Bloor (9 January 2020). "Holding the Spanish Super Cup in Saudi Arabia is not about using football as a force for good. It's about money". fourfourtwo.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- Ghosh, Ratul (12 January 2022). "Saudi Arabia Hosting The Spanish Super Cup: Makes Sense? Not Really". FootTheBall. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "Why is Spanish Supercopa in Saudi Arabia? Reasons first domestic trophy in Spain is played in Middle East". www.sportingnews.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- Lloyd, Simon. "Over The Rainbow: How Hungary sportswashed its way to the front of UEFA's queue". Sports Joe. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- Kunti, Samindra. "Azerbaijan's Sportswashing Culminates With Euro 2020 Quarterfinal". Forbes. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- "Green light for controversial Copa America to get underway". Marca. 11 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- Gowler, Michael (25 October 2021). "Barcelona's Diego Maradona tribute slammed after Napoli snub and Saudi Arabia decision". Daily Mirror. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Dendoune, Nadir (12 July 2021). "Une campagne sur Twitter pour que le Trophée des Champions ne se joue pas en Israël" [A campaign on Twitter to prevent Trophée des Champions from being played in Israel] (in French). Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Baraka, Carey (22 August 2019). "CAREY BARAKA - Sports Washing and Politics in African Football | The Elephant". Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "TROPHÉE DES CHAMPIONS - La Brigade Loire fait le choix de boycotter le Trophée des champions en Israël" [La Brigade Loire chooses to boycott Trophée des Champions in Israel]. Eurosport (in French). 23 July 2022. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- samidoun (31 July 2022). "Toulouse mobilization denounces the Champions Trophy in Tel Aviv". Samidoun: Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- Delaney, Miguel (24 March 2021). "Should football boycott the Qatar World Cup?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- https://amp.theguardian.com/football/2023/mar/16/fifa-defeat-saudi-sponsorship-womens-world-cup-plans-infantino

- "Qatar replaces China as AFC Asian Cup 2023 host". ESPN.com. 17 October 2022. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "FIFA's award of the World Cup to Saudi Arabia is blatant sports washing". Amnesty International. 14 February 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- "Saudi Arabia's hosting of 2027 AFC Asian Cup is an idea whose time has finally come". Arab News. 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- Rondina, Steven (2 December 2019). "BLAST Global Finals part of problematic Middle East esports push – CS:GO – News". WIN.gg.

- "BLAST announces controversial sponsorship with NEOM". Daily Esports. 30 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Chalk, Andy (29 July 2020). "Riot scraps controversial LEC partnership with Saudi Arabia following fan backlash". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Carpenter, Nicole (29 July 2020). "League of Legends' Saudi Arabian partnership criticized by Riot community". Polygon. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Thomas, Harrison (21 December 2022). "Calls grow for Danish government to slash BLAST funding if CS:GO event doesn't cut Abu Dhabi ties". Dot Esports. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- Graham, Michael (7 March 2022). "Graham: The PGA Tour's sportswashing problem in China". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Warner, Ed (10 February 2022). "Ed Warner | Saudi Arabia's new sportswashing exercise leaves PGA and DP World Tours powerless in tussle for golf's superstars". sportspromedia.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "Despite absence of big names, Saudi-backed golf league to begin in June". The Washington Post.

- Schad, Tom. "LIV Golf shines spotlight on 'sportswashing' – the nascent term for an age-old strategy". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- Mike Guy (June 2017). "A Reminder That F1 Is a Very Shady Business". Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Circuits: Buenos Aires (Autodromo Oscar Galvez)". grandprix.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Drumond, Maurício (July 2013). "For the good of sport and the nation: relations between sport and politics in the Portuguese New State (1933-1945)". Revista Estudos Políticos. 4 (8): 319–340. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Miguel Delaney (10 June 2020). "Sportswashing is not new – but has never been more insidious". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- Martin, Gordon (17 September 1985). "The Apartheid Controversy Reaches Formula 1 Racing". San Francisco Chronicle (FINAL ed.). p. 63.

- Mclaughlin, Joshua (October 2021). "Sportswashing: its meaning and impact on the future of F1". Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "See the Timeline of the Military Dictatorship, from 1964 to 1985". 29 June 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Bahrain's grim human rights violations are behind the glamour of the Grand Prix". www.amnesty.org. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- Sagnier, Pierre (26 July 2021). "Sportswashing: the gulf countries' strategy to mask abysmal human rights records". Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Don't let Formula 1 sportswash Azerbaijan's human rights abuses". humanrightshouse.org. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "AP Interview: Saudi prince says sports is a tool for change". ABC News. 19 December 2019. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Ibrahim, Raka (23 November 2019). "Mengapa Kita Ngotot Menggelar Formula E & MotoGP? Sportswashing" [Why Do We Insist on Formula E & MotoGP? Sportswashing] (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Alle Grand-Prix uitslagen en bijzonderheden, van 1973 (het jaar dat Jack begon met racen) tot heden". Archive.li. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- Chandran, Rina. "Indonesia's tourism mega-project 'tramples' on human rights, U.N. says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- David Emmet (28 April 2021). "VR46 Team Announces Saudi Backing For MotoGP Project - Sportwashing Or Business As Usual?". Asphalt and Rubber. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "France raises human rights concerns as Dakar Rally begins in Saudi Arabia". RFI. 5 January 2020. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Smith, Damien (22 November 2022). "WTCR's Jeddah swansong shows Saudi's powerful motor sport pull". Motorsport Magazine. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Aleksandrov, Alexei; Aleksandrov, Grebeniuk; Runets, Volodymyr (22 July 2020). "The 1980 Olympics Are The 'Cleanest' In History. Athletes Recall How Moscow Cheated The System". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- Worden, Minky (4 January 2022). "Opinion: Human rights abuses will taint the Olympics and the World Cup. It's time to end 'sportswashing' now". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Manheim, Jarol (1990). "Rites of Passage: The 1988 Seoul Olympics as Public Diplomacy". The Western Political Quarterly. Western Political Science Association. 43 (2): 279–295. doi:10.2307/448367. JSTOR 448367.

- Kang, Jaeho; Traganou, Jilly (2011). "The Beijing National Stadium as Media-space". Design and Culture. 3 (2): 145–163. doi:10.2752/175470811X13002771867761. S2CID 143762612.

- "Op-Ed: As 2022 Olympics host, China escalated human rights abuses. Will IOC look the other way?". Los Angeles Times. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- "The Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics is a political tinderbox for Russia". The Guardian. 2 January 2013. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- "Explainer: Why human rights matter at the World Cup". www.amnesty.org. 14 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Rio's preparations for this summer's Olympics risk unleashing a new wave of police violence against favela residents and protestors". Amnesty International. 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022.

- Field, Russell. "2022 Winter Olympics will help Beijing 'sportwash' its human rights record". theconversation.com. The Conversation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "Amnesty warns over 'sportswashing' at Beijing Olympics". www.france24.com. France 24. 19 January 2022. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- "Sports in Middle East 'fastest growing in the world', survey finds". The New Arab. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "WTA says it is prepared to pull China tournaments over Peng Shuai". Al-Jazeera. 19 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Ojst, Javier (20 May 2021). "Collision In Korea – Wrestling's Bizarre Political Game in a Land of War". prowrestlingstories.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Ahmed, Tufayel (31 October 2019). "WWE, Saudi Arabia 'Sportswashing' Country's 'Dire Human Rights Record' With First-ever Women's Match". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Zidan, Karim (15 July 2020). "Did Abu Dhabi plant PR reps at UFC 251 press conference to promote UAE tourism?". Bloody Elbow. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Smith, Michael David (7 April 2016). "Some teams aren't on board with NFL's plans to play in China". ProFootballTalk. NBC Sports. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Oliver, Brian (22 July 2014). "The forgotten story of … Robert Maxwell's 1986 Commonwealth Games | Sport | theguardian.com". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "The Dirty Art of Sportswashing". Culture in Sport. 16 April 2021. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Doggers, Peter (28 September 2016). "2017 Women's World Championship Awarded To Iran; Other FIDE Decisions - Chess.com". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- "Belarus Understands the Diplomatic Power of Sport". The Guardian. 11 June 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "China's rulers see the coronavirus as a chance to tighten their grip". The Economist. 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "SEA Games 2019 displaces Aeta communities". 8 December 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- PhosAgro. "World Chess Championship 2021 starts in Dubai". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Wang, Amber; Taylor, Jerome (6 August 2021). "Taiwan won't attend Hong Kong's Gay Games fearing security law". Hong Kong Free Press.

- Garrison, Mark (8 August 2021). "CONTROVERSY SURROUNDS ASIA'S FIRST GAY GAMES IN HONG KONG". Star Observer. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "Hungary". Amnesty. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Palmer, Dan (16 December 2020). "Doha to host 2030 Asian Games with Riyadh awarded 2034 edition". insidethegames.biz. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "The Sportswashing of Corruption". Fourth Floor. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Black, Liam (16 July 2020). "How Sportswashing Is Taking Over Football". Sporting Ferret. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "Partnership between S04 and GAZPROM ends prematurely". FC Schalke 04. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- Meadows, Mark; Ford, Matt (2 March 2022). "Roman Abramovich puts Chelsea up for sale as Russian money trail in sport draws attention". DW. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- "Manchester United official club statement on Aeroflot". Manchester United Official Website. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "Bayern Munich Fans Ramp Up Criticism of Club's Ties to Qatar". Sports Illustrated. 9 November 2021. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Ford, Matt; McKinnon, Kyle (12 August 2021). "Messi, PSG, Qatar, FFP, sportswashing and geopolitics: quo vadis, football?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Klein, Thomas (3 January 2018). "'Bayern Munich cannot remain silent'". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- https://fcbayern.com/en/news/2023/06/joint-statement-fc-bayern-munich-and-qatar-airways

- Gibson, Owen (1 May 2014). "Azerbaijan's sponsorship of Atlético Madrid proves spectacular success". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Kilpatrick, Dan (1 November 2022). "Tottenham urged to ditch Chinese main sponsor AIA and 'show support for human rights and freedom'". standard.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Farrell, Paul (10 September 2014). "'AFL 'reassessing' sponsorship with Royal Brunei after gay protests'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- "AFL Europe to terminate controversial deal with Royal Brunei Airlines". SportBusiness. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Ingle, Sean (10 October 2022). "Absurd': British Cycling faces backlash after announcing partnership with Shell". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- "Saudi-owned LIV Golf "Sportswashes" Rights Abuses". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- Kate Walker (20 December 2015). "Analysis: The real cost of PDVSA sponsoring Pastor Maldonado". motorsport.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- "Gordon Wins TRAXXAS Race At Long Beach". Stadium Super Trucks. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Venezuelan driver believes sponsor money will stay in IndyCar". The Florida Times-Union. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Jordan and China form TV alliance". Motorsport.com. 3 March 2003. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022.

- David Emmet (29 April 2021). "The Ramifications of Saudi Arabia Backing VR46's Move into MotoGP". Asphalt and Rubber. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Aramco announces sponsorship of Formula 1". Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- Brittle, Cian (14 March 2023). "Aston Martin name Saudia as global airline sponsor". SportsPro. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- "NEOM partners with Mercedes EQ Formula E team". Arab News. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- "Saudi Arabia's PIF-backed Neom partners McLaren in FE, XE". Motorsport Week. 27 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Noble, Johnathan (14 April 2022). "Haas rejects Uralkali request to repay F1 sponsorship money". motorsport.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Bouzidi, Lyes (15 October 2021). "Newcastle United Takeover: How far is too far?". Sports Gazzette. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Brewin, John (10 January 2019). "How soccer become a geopolitical tool of influence". Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- Mauro, Ezio (14 September 2005). "L'ultima legge ad personam" (in Italian). la Repubblica. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "Ecco le leggi che hanno aiutato Berlusconi" (in Italian). la Repubblica. 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "L'elenco delle leggi ad personam" (in Italian). 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Bianchi, Fulvio (1 November 2003). "UE, bocciato il decreto salva-calcio. Molte società a rischio fallimento" (in Italian). la Repubblica. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "Prosciolti Galliani, Milan e Inter" (in Italian). Il Sole 24 Ore. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

it: Assolto perché il fatto non costituisce reato.

[Acquitted because the act does not constitute a crime.] - Alfano, Sonia (18 May 2011). "I Milan Club chiedono di votare Berlusconi" (in Italian). Il Fatto Quotidiano. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Jensen, Neil Fredrik (17 August 2019). "Does football really have a moral code?". Game of The People. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Conn, David (7 August 2018). "Stan Kroenke's £550m offer to buy outright ownership of Arsenal is accepted". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Want to know how successful sportswashing is? Just look at the Manchester City fans who cheerlead for Abu Dhabi". inews.co.uk. 30 November 2018. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Hemmingham, Nathan (25 April 2020). "Why Sheffield United are being drawn into Saudi backlash as a result of Newcastle takeover bid". YorkshireLive. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- "Saudi crown prince asked Boris Johnson to intervene in Newcastle United bid". The Guardian. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- "Several Paris-based NGOs call upon the Mairie de Paris to cease all form of support for Bahrain "sport-washing" campaign". Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain. 2 February 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Le Qatar sans limite". leparisien.fr (in French). 7 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Puspaningrum, Bernadette Aderi (27 September 2021). "Kepemilikan Asing Brisbane Roar Bermasalah, Nama Joko Driyono dan Bakrie Dicatut" [Foreign Ownership of Brisbane Roar Deemed Troublesome, As Joko Driyono and Bakrie Name Was Put Under Spotlight]. Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Indonesia. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Stephanie Yang (15 December 2020). "Washington Spirit partnership with Qatar is troubling". All for XI. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Kosman, Josh; Lewis, Brian (1 March 2022). "Did Vladimir Putin pressure Mikhail Prokhorov to sell the Brooklyn Nets?". New York Post. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- Fainaru-Wada, Mark; Fainaru, Steve (14 April 2022). "Brooklyn Nets owner Joe Tsai is the face of NBA's uneasy China relationship". ESPN. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- V Singh, Vijay (19 June 2018). "Vijay Mallya used Force India, RCB for laundering: ED chargesheet". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Pg 35-71, Peter May, The Rebel Tours: Cricket's Crisis of Conscience, 2009

- Pg 55, May 2009

- Kennedy, Tristan (21 September 2020). "The 'Sportswashing' Behind One of the World's Biggest Cycling Teams". Vice News. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Dudley, Dominic (22 September 2020). "UAE Scores A Victory Over Bahrain And Israel In Soft Power Arena Of Tour De France". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Fildes, Nic (14 March 2013). "Bahrain violence convinces Vodafone to end its F1 deal". The Times. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Forde, Pat. "The Derby, the Sheikh and the Missing Princess: A Troubling Mix". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- updated, Tyler Wilde last (25 January 2022). "Major esports host ESL Gaming is now owned by Saudi Arabia". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Dawson, Alan. "Daniel Kinahan appears to be at the heart of a campaign to sportswash his image as the suspected boss of a $1 billion cartel". Insider. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Reyes, Gerardo; Ocando, Cato (4 August 2013). "Boliburgueses y el encanto del Imperio". Univision. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Quarantine prize money of Chechen horse: Greens". Sydney Morning Gerald. 3 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- "The President of Turkmenistan Awarded with UCI Certificate". Business.com. 4 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.