Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan (Latin: Aurelius Ambrosius; c. 339 – 4 April 397), venerated as Saint Ambrose,[lower-alpha 1] was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promoting Roman Christianity against Arianism and paganism.[5] He left a substantial collection of writings, of which the best known include the ethical commentary De officiis ministrorum (377–391), and the exegetical Exameron (386–390). His preachings, his actions and his literary works, in addition to his innovative musical hymnography, made him one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century.

Ambrose of Milan | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Milan | |

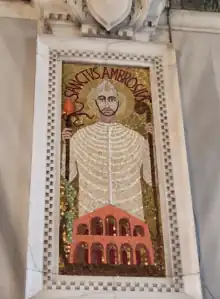

.jpg.webp) Detail from possibly contemporary mosaic (c. 380–500) of Ambrose in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio[1] | |

| Diocese | Mediolanum (Milan) |

| See | Mediolanum |

| Installed | 374 AD |

| Term ended | 4 April 397 |

| Predecessor | Auxentius |

| Successor | Simplician |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 7 December 374 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Aurelius Ambrosius c. 339 |

| Died | 4 April 397 (aged 56–57) Mediolanum, Italia, Roman Empire (modern-day Milan, Italy) |

| Buried | Crypt of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio |

| Denomination | Christian |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 7 December |

| Venerated in | |

| Title as Saint | Doctor of the Church |

| Patronage | Milan and beekeepers[2]

Other patronage

|

| Shrines | Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio |

Theology career | |

| Notable work |

|

| Theological work | |

| Era | Patristic Age |

| Tradition or movement | Trinitarianism |

| Main interests | Christian ethics and mariology |

| Notable ideas | Anti-paganism, mother of the Church[4] |

Ambrose was serving as the Roman governor of Aemilia-Liguria in Milan when he was unexpectedly made Bishop of Milan in 374 by popular acclamation. As bishop, he took a firm position against Arianism and attempted to mediate the conflict between the emperors Theodosius I and Magnus Maximus. Tradition credits Ambrose with developing an antiphonal chant, known as Ambrosian chant, and for composing the "Te Deum" hymn, though modern scholars now reject both of these attributions. Ambrose's authorship on at least four hymns, including the well-known "Veni redemptor gentium", is secure; they form the core of the Ambrosian hymns, which includes others that are sometimes attributed to him. He also had notable influence on Augustine of Hippo (354–430), whom he helped convert to Christianity.

Western Christianity identified Ambrose as one of its four traditional Doctors of the Church. He is considered a saint by the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, and various Lutheran denominations, and venerated as the patron saint of Milan and beekeepers.

Background and career

.jpg.webp) Painting by Michael Pacher

Painting by Michael Pacher Engraving of a statue of Ambrose

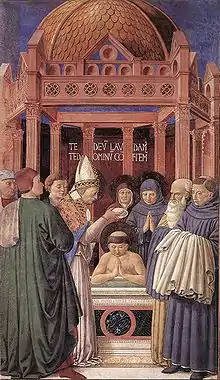

Engraving of a statue of Ambrose Painting of Ambrose' Baptism by Gozzoli

Painting of Ambrose' Baptism by Gozzoli

Legends about Ambrose had spread through the empire long before his biography was written, making it difficult for modern historians to understand his true character and fairly place his behavior within the context of antiquity. Most agree he was the personification of his era.[6][7] This would make Ambrose a genuinely spiritual man who spoke up and defended his faith against opponents, an aristocrat who retained many of the attitudes and practices of a Roman governor, and also an ascetic who served the poor.[8]

Early life

Ambrose was born into a Roman Christian family in the year 339.[10] Ambrose himself wrote that he was 53 years old in his letter number 49, which has been dated to 392. He began life in Augusta Trevorum (modern Trier) the capital of the Roman province of Gallia Belgica in what was then northeastern Gaul and is now in the Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany.[11] Scholars disagree on who exactly his father was. His father is sometimes identified with Aurelius Ambrosius,[12][lower-alpha 2] a praetorian prefect of Gaul;[14] but some scholars identify his father as an official named Uranius who received an imperial constitution dated 3 February 339 (addressed in a brief extract from one of the three emperors ruling in 339, Constantine II, Constantius II, or Constans, in the Codex Theodosianus, book XI.5).[15][16] What does seem certain is that Ambrose was born in Trier and his father was either the praetorian prefect or part of his administration.[17]

A legend about Ambrose as an infant recounts that a swarm of bees settled on his face while he lay in his cradle, leaving behind a drop of honey. His father is said to have considered this a sign of his future eloquence and honeyed tongue. Bees and beehives often appear in the saint's symbology.[18]

Ambrose' mother was a woman of intellect and piety.[19] It was probable that she was a member of the Roman family Aurelii Symmachi,[20] which would make Ambrose a cousin of the orator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus.[21] The family had produced one martyr (the virgin Soteris) in its history.[22] Ambrose was the youngest of three children. His siblings were Satyrus, the subject of Ambrose's De excessu fratris Satyri,[23] and Marcellina, who made a profession of virginity sometime between 352 and 355; Pope Liberius himself conferred the veil upon her.[24] Both Ambrose's siblings also became venerated as saints.

Some time early in the life of Ambrose, his father died. At an unknown later date, his mother fled Trier with her three children, and the family moved to Rome.[25][26] There Ambrose studied literature, law, and rhetoric.[22] He then followed in his father's footsteps and entered public service. Praetorian Prefect Sextus Claudius Petronius Probus first gave him a place as a judicial councillor,[27] and then in about 372 made him governor of the province of Liguria and Emilia, with headquarters at Milan.[14] [28]

Bishop of Milan

In 374 the bishop of Milan, Auxentius, an Arian, died, and the Arians challenged the succession. Ambrose went to the church where the election was to take place to prevent an uproar which seemed probable in this crisis. His address was interrupted by a call, "Ambrose, bishop!", which was taken up by the whole assembly.[29]

Ambrose, though known to be Nicene Christian in belief, was considered acceptable to Arians due to the charity he had shown concerning their beliefs. At first he energetically refused the office of bishop, for which he felt he was in no way prepared: Ambrose was a relatively new Christian who was not yet baptized nor formally trained in theology.[14] Ambrose fled to a colleague's home, seeking to hide. Upon receiving a letter from the Emperor Gratian praising the appropriateness of Rome appointing individuals worthy of holy positions, Ambrose's host gave him up. Within a week, he was baptized, ordained and duly consecrated as the new bishop of Milan. This was the first time in the West that a member of the upper class of high officials had accepted the office of bishop.[30]

As bishop, he immediately adopted an ascetic lifestyle, apportioned his money to the poor, donating all of his land, making only provision for his sister Marcellina. This raised his standing even further; it was his popularity with the people that gave him considerable political leverage throughout his career. Upon the unexpected appointment of Ambrose to the episcopate, his brother Satyrus resigned a prefecture in order to move to Milan, where he took over managing the diocese's temporal affairs.[11]

Arianism

Arius (died 336) was a Christian priest who asserted (around the year 300) that God the Father must have created the Son, making the Son a lesser being who was not eternal and of a different "essence" than God the Father. This Christology, though contrary to tradition, quickly spread through Egypt and Libya and other Roman provinces.[31] Bishops engaged in "wordy warfare", and the people divided into parties, sometimes demonstrating in the streets in support of one side or the other.[32]

Arianism appealed to many high-level leaders and clergy in both the Western and Eastern empires. Although the western Emperor Gratian (r. 367–383) supported orthodoxy, his younger half brother Valentinian II, who became his colleague in the empire in 375, adhered to the Arian creed.[33] Ambrose sought to refute Arian propositions theologically, but Ambrose did not sway the young prince's position.[33] In the East, Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395) likewise professed the Nicene creed; but there were many adherents of Arianism throughout his dominions,[19] especially among the higher clergy.

In this state of religious ferment, two leaders of the Arians, bishops Palladius of Ratiaria and Secundianus of Singidunum, confident of numbers, prevailed upon Gratian to call a general council from all parts of the empire. This request appeared so equitable that Gratian complied without hesitation. However, Ambrose feared the consequences and prevailed upon the emperor to have the matter determined by a council of the Western bishops. Accordingly, a synod composed of thirty-two bishops was held at Aquileia in the year 381. Ambrose was elected president and Palladius, being called upon to defend his opinions, declined. A vote was then taken and Palladius and his associate Secundianus were deposed from their episcopal offices.[19]

Ambrose struggled with Arianism for over half of his term in the episcopate.[34] Ecclesiastical unity was important to the church, but it was no less important to the state, and as a Roman, Ambrose felt strongly about that.[35] Judaism was more attractive for those seeking conversion than previous scholars have realized,[36] and pagans were still in the majority. Conflict over heresies loomed large in an age of religious ferment comparable to the Reformation of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[37] Orthodox Christianity was determining how to define itself as it faced multiple challenges on both a theological and a practical level,[38] and Ambrose exercised crucial influence at a crucial time.[39]

Imperial relations

Ambrose had good relations and varying levels of influence with the Roman emperors Gratian, Valentinian II and Theodosius I, but exactly how much influence, what kind of influence, and in what ways, when, has been debated in the scholarship of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.[40][41][42]

Gratian

It has long been convention to see Gratian and Ambrose as having a personal friendship, putting Ambrose in the dominant role of spiritual guide, but modern scholars now find this view hard to support from the sources.[43] The ancient Christian historian Sozomen (c. 400 – c. 450) is the only ancient source that shows Ambrose and Gratian together in any personal interaction. In that interaction, Sozomen relates that, in the last year of Gratian's reign, Ambrose crashed Gratian's private hunting-party in order to appeal on behalf of a pagan senator sentenced to die. After years of acquaintance, this indicates that Ambrose could not take for granted that Gratian would see him, so instead, Ambrose had to resort to such maneuverings to make his appeal.[44]

Gratian was personally devout long before meeting Ambrose.[45] Modern scholarship indicates Gratian's religious policies do not evidence capitulation to Ambrose more than they evidence Gratian's own views.[44] Gratian's devotion did lead Ambrose to write a large number of books and letters of theology and spiritual commentary dedicated to the emperor. The sheer volume of these writings and the effusive praise they contain has led many historians to conclude that Gratian was dominated by Ambrose, and it was that dominance that produced Gratian's anti-pagan actions.[44] McLynn asserts that effusive praises were common in everyone's correspondence with the crown. He adds that Gratian's actions were determined by the constraints of the system as much as "by his own initiatives or Ambrose's influence".[44]

McLynn asserts that the largest influence on Gratian's policy was the profound change in political circumstances produced by the Battle of Adrianople in 378.[46] Gratian had become involved in fighting the Goths the previous year and had been on his way to the Balkans when his uncle and the "cream of the eastern army" were destroyed at Adrianople. Gratian withdrew to Sirmium and set up his court there.[47] Several rival groups, including the Arians, sought to secure benefits from the government at Sirmium.[47] In an Arian attempt to undermine Ambrose, whom Gratian had not yet met, Gratian was "warned" that Ambrose' faith was suspect. Gratian took steps to investigate by writing to Ambrose and asking him to explain his faith.[48]

Ambrose and Gratian first met, after this, in 379 during a visit to Milan. The bishop made a good impression on Gratian and his court, which was pervasively Christian and aristocratic – much like Ambrose himself. [lower-alpha 3] The emperor returned to Milan in 380 to find that Ambrose had complied with his request for a statement of his faith – in two volumes – known as De Fide: a statement of orthodoxy and of Ambrose' political theology, as well as a polemic against the Arian heresy – intended for public discussion.[51] The emperor had not asked to be instructed by Ambrose, and in De Fide Ambrose states this clearly. Nor was he asked to refute the Arians. He was asked to justify his own position, but in the end, he did all three.[52]

It seems that by 382 Ambrose had replaced Ausonius to become a major influence in Gratian's court. Ambrose had not yet become the "conscience" of kings he would in the later 380s, but he did speak out against reinstating the Altar of Victory.[53] In 382, Gratian was the first to divert public financial subsidies that had previously supported Rome's cults. Before that year, contributions in support of the ancient customs had continued unchallenged by the state.[54]

Valentinian II

The childless Gratian had treated his younger brother Valentinian II like a son.[55] Ambrose, on the other hand, had incurred the lasting enmity of Valentinian II's mother, the Empress Justina, in the winter of 379 by helping to appoint a Nicene bishop in Sirmium. Not long after this, Valentinian II, his mother, and the court left Sirmium; Sirmium had come under Theodosius' control, so they went to Milan which was ruled by Gratian.[56]

In 383 Gratian was assassinated at Lyon, in Gaul (France) by Magnus Maximus. Valentinian was twelve years old, and the assassination left his mother, Justina, in a position of something akin to a regent.[57] In 385 (or 386) the emperor Valentinian II and his mother Justina, along with a considerable number of clergy, the laity, and the military, professed Arianism.[33] Conflict between Ambrose and Justina soon followed.

The Arians demanded that Valentinian allocate to them two churches in Milan: one in the city (the Basilica of the Apostles), the other in the suburbs (St Victor's).[33] Ambrose refused to surrender the churches. He answered by saying that "What belongs to God, is outside the emperor's power." In this, Ambrose called on an ancient Roman principle: a temple set apart to a god became the property of that god. Ambrose now applied this ancient legal principle to the Christian churches, seeing the bishop, as a divine representative, as guardian of his god's property.[58]

Subsequently, while Ambrose was performing the Liturgy of the Hours in the basilica, the prefect of the city came to persuade him to give it up to the Arians. Ambrose again refused. Certain deans (officers of the court) were sent to take possession of the basilica by hanging upon it imperial escutcheons.[33][59] Instead, soldiers from the ranks the emperor had placed around the basilica began pouring into the church, assuring Ambrose of their fidelity. The escutcheons outside the church were removed, and legend says the children tore them to shreds.[58]

Ambrose refused to surrender the basilica, and sent sharp answers back to his emperor: "If you demand my person, I am ready to submit: carry me to prison or to death, I will not resist; but I will never betray the church of Christ. I will not call upon the people to succour me; I will die at the foot of the altar rather than desert it. The tumult of the people I will not encourage: but God alone can appease it."[59] By Thursday, the emperor gave in, bitterly responding: "Soon, if Ambrose gives the orders, you will be sending me to him in chains."[60]

In 386, Justina and Valentinian II received the Arian bishop Auxentius the younger, and Ambrose was again ordered to hand over a church in Milan for Arian usage. Ambrose and his congregation barricaded themselves inside the church, and again the imperial order was rescinded.[61] There was an attempted kidnapping, and another attempt to arrest him and to force him to leave the city.[62] Several accusations were made, but unlike in the case of John Chrysostom, no formal charges were brought. The emperor certainly had the power to do so, and probably did not solely because of Ambrose' popularity with the people and what they might do.[63]

When Magnus Maximus usurped power in Gaul (383) and was considering a descent upon Italy, Valentinian sent Ambrose to dissuade him, and the embassy was successful (384).[59] A second, later embassy was unsuccessful. Magnus Maximus entered Italy (386-387) and Milan was taken. Justina and her son fled, but Ambrose remained, and had the plate of the church melted for the relief of the poor.[59]

After defeating the usurper Maximus at Aquileia in 388 Theodosius handed the western realm back to the young Valentinian II, the seventeen-year-old son of the forceful and hardy Pannonian general Valentinian I and his wife, the Arian Justina. Furthermore, the Eastern emperor remained in Italy for a considerable period to supervise affairs, returning to Constantinople in 391 and leaving behind the Frankish general Arbogast to keep an eye on the young emperor. By May of the following year Arbogast's ward was dead amidst rumours of both treachery and suicide...[64]

Theodosius

While Ambrose was writing De Fide, Theodosius published his own statement of faith in 381 in an edict establishing Nicene Catholic Christianity as the only legitimate version of the Christian faith. There is unanimity amongst scholars that this represents the emperor's own beliefs.[65] The aftermath of the death (378) of Valens (Emperor in the East from 364 to 378) had left many questions for the church unresolved, and Theodosius' edict can be seen as an effort to begin addressing those questions.[66] Theodosius' natural generosity was tempered by his pressing need to establish himself and to publicly assert his personal piety.[67]

On 28 February 380, Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica, a decree addressed to the city of Constantinople, determining that only Christians who did not support Arian views were catholic and could have their places of worship officially recognized as "churches".[68][35][lower-alpha 4] The Edict opposed Arianism, and attempted to establish unity in Christianity and to suppress heresy.[71] German ancient historian Karl Leo Noethlichs writes that the Edict of Thessalonica was neither anti-pagan nor antisemitic; it did not declare Christianity to be the official religion of the empire; and it gave no advantage to Christians over other faiths.[72]

Liebeschuetz and Hill indicate that it was not until after 388, during Theodosius' stay in Milan following the defeat of Maximus in 388, that Theodosius and Ambrose first met.[73]

After the Massacre of Thessalonica in 390, Theodosius made an act of public penance at Ambrose's behest.[75] Ambrose was away from court during the events at Thessalonica, but after being informed of them, he wrote Theodosius a letter.[76] In that still existing letter, Ambrose presses for a semi-public demonstration of penitence from the emperor, telling him that, as his bishop, he will not give Theodosius communion until it is done. Wolf Liebeschuetz says "Theodosius duly complied and came to church without his imperial robes, until Christmas, when Ambrose openly admitted him to communion".[77]

Formerly, some scholars credited Ambrose with having an undue influence over the Emperor Theodosius I, from this period forward, prompting him toward major anti-pagan legislation beginning in February of 391.[78][79][80] However, this interpretation has been heavily disputed since the late-twentieth century. McLynn argues that Theodosius's anti-pagan legislation was too limited in scope for it to be of interest to the bishop.[81][82] The fabled encounter at the door of the cathedral in Milan, with Ambrose as the mitred prelate braced, blocking Theodosius from entering, which has sometimes been seen as evidence of Ambrose' dominance over Theodosius, has been debunked by modern historians as "a pious fiction".[83][84] There was no encounter at the church door.[85][86][87][88] The story is a product of the imagination of Theodoret, a historian of the fifth century who wrote of the events of 390 "using his own ideology to fill the gaps in the historical record".[89]

The twenty-first century view is that Ambrose was "not a power behind the throne".[83] The two men did not meet each other frequently, and documents that reveal the relationship between the two are less about personal friendship than they are about negotiations between two formidable leaders of the powerful institutions they represent: the Roman State and the Italian Church.[90] Cameron says there is no evidence that Ambrose was a significant influence on the emperor.[91]

For centuries after his death, Theodosius was regarded as a champion of Christian orthodoxy who decisively stamped out paganism. This view was recorded by Theodoret, who is recognized as an unreliable historian, in the century following their deaths.[92] Theodosius's predecessors Constantine (r. 306–337), Constantius (r. 337–361), and Valens had all been semi-Arians. Therefore, it fell to the orthodox Theodosius to receive from Christian literary tradition most of the credit for the final triumph of Christianity.[93] Modern scholars see this as an interpretation of history by orthodox Christian writers more than as a representation of actual history.[94][95][96][97] The view of a pious Theodosius submitting meekly to the authority of the church, represented by Ambrose, is part of the myth that evolved within a generation of their deaths.[98]

Later years and death

In April 393 Arbogast (magister militum of the West) and his puppet Emperor Eugenius marched into Italy to consolidate their position in regard to Theodosius I and his son, Honorius, whom Theodosius had appointed Augustus to govern the western portion of the empire. Arbogast and Eugenius courted Ambrose's support by very obliging letters; but before they arrived at Milan, he had retired to Bologna, where he assisted at the translation of the relics of Saints Vitalis and Agricola. From there he went to Florence, where he remained until Eugenius withdrew from Milan to meet Theodosius in the Battle of the Frigidus in early September 394.[99]

Soon after acquiring the undisputed possession of the Roman Empire, Theodosius died at Milan in 395, and Ambrose gave the eulogy.[100] Two years later (4 April 397) Ambrose also died. He was succeeded as bishop of Milan by Simplician.[59] Ambrose's body may still be viewed in the church of Saint Ambrogio in Milan, where it has been continuously venerated – along with the bodies identified in his time as being those of Saints Gervase and Protase.

Ambrose is remembered in the calendar of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church on 7 December, and is also honored in the Church of England and in the Episcopal Church on 7 December.[101][102]

Character

In 1960, Neil B. McLynn wrote a complex study of Ambrose that focused on his politics and intended to "demonstrate that Ambrose viewed community as a means to acquire personal political power". Subsequent studies of how Ambrose handled his episcopal responsibilities, his Nicene theology and his dealings with the Arians in his episcopate, his pastoral care, his commitment to community, and his personal asceticism, have mitigated this view.[103][104]

.jpg.webp)

All of Ambrose' writings are works of advocacy of his religion, and even his political views and actions were closely related to his religion.[105] He was rarely, if ever, concerned about simply recording what had happened; he did not write to reveal his inner thoughts and struggles; he wrote to advocate for his God.[106] Boniface Ramsey writes that it is difficult "not to posit a deep spirituality in a man" who wrote on the mystical meanings of the Song of Songs and wrote many extraordinary hymns.[107] In spite of an abiding spirituality, Ambrose had a generally straightforward manner, and a practical rather than a speculative tendency in his thinking.[108] De Officiis is a utilitarian guide for his clergy in their daily ministry in the Milanese church rather than "an intellectual tour de force".[109]

Christian faith in the third century developed the monastic life-style which subsequently spread into the rest of Roman society in a general practice of virginity, voluntary poverty and self-denial for religious reasons. This life-style was embraced by many new converts, including Ambrose, even though they did not become actual monks.[110]

The bishops of this era had heavy administrative responsibilities, and Ambrose was also sometimes occupied with imperial affairs, but he still fulfilled his primary responsibility to care for the well-being of his flock. He preached and celebrated the Eucharist multiple times a week, sometimes daily, dealt directly with the needs of the poor, as well as widows and orphans, "virgins" (nuns), and his own clergy. He replied to letters personally, practiced hospitality, and made himself available to the people.[111]

Ambrose had the ability to maintain good relationships with all kinds of people.[112] Local church practices varied quite a bit from place to place at this time, and as the bishop, Ambrose could have required that everyone adapt to his way of doing things. It was his place to keep the churches as united as possible in both ritual and belief.[24] Instead, he respected local customs, adapting himself to whatever practices prevailed, instructing his mother to do the same.[113] As bishop, Ambrose undertook many different labors in an effort to unite people and "provide some stability during a period of religious, political, military, and social upheavals and transformations".[114]

Brown says Ambrose "had the makings of a faction fighter".[115] While he got along well with most people, Ambrose was not averse to conflict and even opposed emperors with a fearlessness born of self-confidence and a clear conscience and not from any belief he would not suffer for his decisions.[116] Having begun his life as a Roman aristocrat and a governor, it is clear that Ambrose retained the attitude and practice of Roman governance even after becoming a bishop.[117]

His acts and writings show he was quite clear about the limits of imperial power over the church's internal affairs including doctrine, moral teaching, and governance. He wrote to Valentinian: "In matters of faith bishops are the judges of Christian emperors, not emperors of bishops." (Epistle 21.4). He also famously told to the Arian bishop chosen by the emperor, "The emperor is in the church, not over the church." (Sermon Against Auxentius, 36). [118][119] Ambrose's acts and writings "created a sort of model which was to remain valid in the Latin West for the relations of the Church and the Christian State. Both powers stood in a basically positive relationship to each other, but the innermost sphere of the Church's life--faith, the moral order, ecclesiastical discipline--remained withdrawn from the State's influence."[119]

Ambrose was also well aware of the limits of his power. At the height of his career as a venerable, respected and well loved bishop in 396, imperial agents marched into his church, pushing past him and his clergy who had crowded the altar to protect a political suspect from arrest, and dragged the man from the church in front of Ambrose who could do nothing to stop it.[120] "When it came to the central functions of the Roman state, even the vivid Ambrose was a lightweight".[120]

Attitude towards Jews

The most notorious example of Ambrose's anti-Jewish animus occurred in 388, when Emperor Theodosius I was informed that a crowd of Christians had retaliated against the local Jewish community by destroying the synagogue at Callinicum on the Euphrates.[121] The synagogue most likely existed within the fortified town to service the soldiers serving there, and Theodosius ordered that the offenders be punished, and that the synagogue be rebuilt at the expense of the bishop.[122] Ambrose wrote to the emperor arguing against this, basing his argument on two assertions: first, if the bishop obeyed the order, it would be a betrayal of his faith.[123] Second, if the bishop instead refused to obey the order, he would become a martyr and create a scandal for the emperor.[123] Ambrose, referring to a prior incident where Magnus Maximus issued an edict censuring Christians in Rome for burning down a Jewish synagogue, warned Theodosius that the people in turn exclaimed "the emperor has become a Jew", implying Theodosius would receive the same lack of support from the people.[124] Theodosius rescinded the order concerning the bishop.[125][123]

That was not enough for Ambrose, and when Theodosius next visited Milan, Ambrose confronted him directly in an effort to get the emperor to drop the entire case. McLynn argues that Ambrose failed to win the emperor's sympathy and was mostly excluded from his counsels thereafter.[126][127] The Callinicum affair was not an isolated incident. Generally speaking, Ambrose presents a strong anti-Jewish polemic.[128] While McLynn says this makes Ambrose look like a bully and a bigot to modern eyes, scholars also agree Ambrose' attitudes toward the Jews cannot be fairly summarized in one sentence, as not all of Ambrose' attitudes toward Jews were negative.[127]

Ambrose makes extensive and appreciative use of the works of Philo of Alexandria – a Jew – in Ambrose' own writings, treating Philo as one of the "faithful interpreters of the Scriptures".[129] Philo was an educated man of some standing and a prolific writer during the era of Second Temple Judaism. Forty–three of his treatises have been preserved, and these by Christians, rather than Jews.[128] Philo became foundational in forming the Christian literary view on the six days of creation through Basil's Hexaemeron. Eusebius, the Cappadocian Fathers, and Didymus the Blind appropriated material from Philo as well, but none did so more than Ambrose. As a result of this extensive referencing, Philo was accepted into the Christian tradition as an honorary Church Father. "In fact, one Byzantine catena even refers to him as 'Bishop Philo'. This high regard for Philo even led to a number of legends of his conversion to Christianity, although this assertion stands on very dubious evidence".[130] Ambrose also used Josephus, Maccabees, and other Jewish sources for his writings. He praises some individual Jews.[131] Ambrose tended to write negatively of all non-Nicenes as if they were all one category. This served a rhetorical purpose in his writing and should be considered accordingly.[132]

Attitude towards pagans

Modern scholarship indicates paganism was a lesser concern than heresy for Christians in the fourth and fifth centuries, which was the case for Ambrose, but it was still a concern.[133] Writings of this period were commonly hostile and often contemptuous toward a paganism Christianity saw as already defeated in Heaven.[134] The great Christian writers of the third to fifth centuries attempted to discredit continuation in these "defeated practices" by searching pagan writings, "particularly those of Varro, for everything that could be regarded by Christian standards as repulsive and irreligious."[135] Ambrose' work reflects this triumphalism.[lower-alpha 5]

Throughout his time in the episcopate, Ambrose was active in his opposition to any state sponsorship of pagan cults.[54] When Gratian ordered the Altar of Victory to be removed, it roused the aristocracy of Rome to send a delegation to the emperor to appeal the decision, but Pope Damasus I got the Christian senators to petition against it, and Ambrose blocked the delegates from getting an audience with the emperor.[140][141][142] Under Valentinian II, an effort was made to restore the Altar of Victory to its ancient station in the hall of the Roman Senate and to again provide support for the seven Vestal Virgins. The pagan party was led by the refined senator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, who used all his prodigious skill and artistry to create a marvelous document full of the maiestas populi Romani.[143] Hans Lietzmann writes that "Pagans and Christians alike were stirred by the solemn earnestness of an admonition which called all men of goodwill to the aid of a glorious history, to render all worthy honor to a world that was fading away".[144]

Then Ambrose wrote Valentinian II a letter asserting that the emperor was a soldier of God, not simply a personal believer but one bound by his position to serve the faith; under no circumstances could he agree to something that would promote the worship of idols.[lower-alpha 6] Ambrose held up the example of Valentinian's brother, Gratian, reminding Valentinian that the commandment of God must take precedence.[147] The bishop's intervention led to the failure of Symmachus' appeal.[148][149]

In 389, Ambrose intervened against a pagan senatorial delegation who wished to see the emperor Theodosius I. Although Theodosius refused their requests, he was irritated at the bishop's presumption and refused to see him for several days.[91] Later, Ambrose wrote a letter to the emperor Eugenius complaining that some gifts the latter had bestowed on pagan senators could be used for funding pagan cults.[150][151]

Theology

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Ambrose joins Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great as one of the Latin Doctors of the Church. Theologians compare him with Hilary, who they claim fell short of Ambrose's administrative excellence but demonstrated greater theological ability. He succeeded as a theologian despite his juridical training and his comparatively late handling of biblical and doctrinal subjects.[59]

Ambrose's intense episcopal consciousness furthered the growing doctrine of the Church and its sacerdotal ministry, while the prevalent asceticism of the day, continuing the Stoic and Ciceronian training of his youth, enabled him to promulgate a lofty standard of Christian ethics. Thus we have the De officiis ministrorum, De viduis, De virginitate and De paenitentia.[59]

Ambrose displayed a kind of liturgical flexibility that kept in mind that liturgy was a tool to serve people in worshiping God, and ought not to become a rigid entity that is invariable from place to place. His advice to Augustine of Hippo on this point was to follow local liturgical custom. "When I am at Rome, I fast on a Saturday; when I am at Milan, I do not. Follow the custom of the church where you are."[152][153] Thus Ambrose refused to be drawn into a false conflict over which particular local church had the "right" liturgical form where there was no substantial problem. His advice has remained in the English language as the saying, "When in Rome, do as the Romans do."

One interpretation of Ambrose's writings is that he was a Christian universalist.[154] It has been noted that Ambrose's theology was significantly influenced by that of Origen and Didymus the Blind, two other early Christian universalists.[154] One quotation cited in favor of this belief is:

Our Savior has appointed two kinds of resurrection in the Apocalypse. 'Blessed is he that hath part in the first resurrection,' for such come to grace without the judgment. As for those who do not come to the first, but are reserved unto the second resurrection, these shall be disciplined until their appointed times, between the first and the second resurrection.[155]

One could interpret this passage as being another example of the mainstream Christian belief in a general resurrection (that both those in Heaven and in Hell undergo a bodily resurrection), or an allusion to purgatory (that some destined for Heaven must first undergo a phase of purification). Several other works by Ambrose clearly teach the mainstream view of salvation. For example: "The Jews feared to believe in manhood taken up into God, and therefore have lost the grace of redemption, because they reject that on which salvation depends."[156]

Giving to the poor

In De Officiis, the most influential of his surviving works, and one of the most important texts of patristic literature, he reveals his views connecting justice and generosity by asserting these practices are of mutual benefit to the participants.[157][158][159] Ambrose draws heavily on Cicero and the biblical book of Genesis for this concept of mutual inter-dependence in society. In the bishop's view, it is concern for one another's interests that binds society together.[160] Ambrose asserts that avarice leads to a breakdown in this mutuality, therefore avarice leads to a breakdown in society itself. In the late 380s, the bishop took the lead in opposing the greed of the elite landowners in Milan by starting a series of pointed sermons directed at his wealthy constituents on the need for the rich to care for the poor.[161]

Some scholars have suggested Ambrose' endeavors to lead his people as both a Roman and a Christian caused him to strive for what a modern context would describe as a type of communism or socialism.[103] He was not just interested in the church but was also interested in the condition of contemporary Italian society.[162] Ambrose considered the poor not a distinct group of outsiders, but a part of a united people to be stood with in solidarity. Giving to the poor was not to be considered an act of generosity towards the fringes of society but a repayment of resources that God had originally bestowed on everyone equally and that the rich had usurped.[163] He defines justice as providing for the poor whom he describes as our "brothers and sisters" because they "share our common humanity".[164]

Mariology

The theological treatises of Ambrose of Milan would come to influence Popes Damasus, Siricius and Leo XIII. Central to Ambrose is the virginity of Mary and her role as Mother of God.[165]

- The virgin birth is worthy of God. Which human birth would have been more worthy of God, than the one in which the Immaculate Son of God maintained the purity of his immaculate origin while becoming human?[166]

- We confess that Christ the Lord was born from a virgin, and therefore we reject the natural order of things. Because she conceived not from a man but from the Holy Spirit.[167]

- Christ is not divided but one. If we adore him as the Son of God, we do not deny his birth from the virgin. ... But nobody shall extend this to Mary. Mary was the temple of God but not God in the temple. Therefore, only the one who was in the temple can be worshiped.[168]

- Yes, truly blessed for having surpassed the priest (Zechariah). While the priest denied, the Virgin rectified the error. No wonder that the Lord, wishing to rescue the world, began his work with Mary. Thus she, through whom salvation was being prepared for all people, would be the first to receive the promised fruit of salvation.[169]

Ambrose viewed celibacy as superior to marriage and saw Mary as the model of virginity.[170]

Augustine

Ambrose studied theology with Simplician, a presbyter of Rome.[19] Using his excellent knowledge of Greek, which was then rare in the West, Ambrose studied the Old Testament and Greek authors like Philo, Origen, Athanasius, and Basil of Caesarea, with whom he was also exchanging letters.[171] Ambrose became a famous rhetorician whom Augustine came to hear speak. Augustine wrote in his Confessions that Faustus, the Manichean rhetorician, was a more impressive speaker, but the content of Ambrose's sermons began to affect Augustine's faith. Augustine sought guidance from Ambrose, and again records in his Confessions that Ambrose was too busy to answer his questions. In a passage of Augustine's Confessions in which Augustine wonders why he could not share his burden with Ambrose, he comments: "Ambrose himself I esteemed a happy man, as the world counted happiness, because great personages held him in honor. Only his celibacy appeared to me a painful burden."[172] Simplician regularly met with Augustine, however, and Augustine writes of Simplician's "fatherly affection" for him. It was Simplician who introduced Augustine to Christian Neoplatonism.[173] It is commonly understood in the Christian Tradition that Ambrose baptized Augustine.

In this same passage of Augustine's Confessions is an anecdote which bears on the history of reading:

When [Ambrose] read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud.[172]

This is a celebrated passage in modern scholarly discussion. The practice of reading to oneself without vocalizing the text was less common in antiquity than it has since become. In a culture that set a high value on oratory and public performances of all kinds, in which the production of books was very labor-intensive, the majority of the population was illiterate, and where those with the leisure to enjoy literary works also had slaves to read for them, written texts were more likely to be seen as scripts for recitation than as vehicles of silent reflection. However, there is also evidence that silent reading did occur in antiquity and that it was not generally regarded as unusual.[174][175][176]

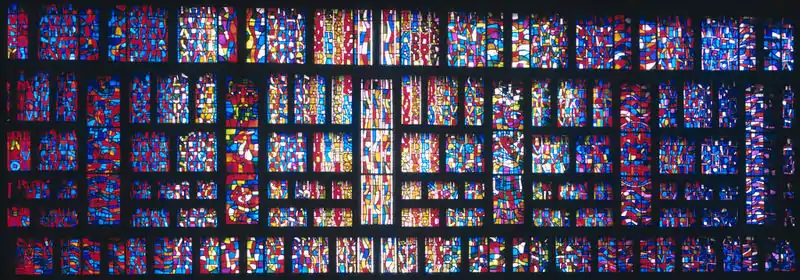

Music

Ambrose's writings extend past literature and into music, where he was an important innovator in early Christian hymnography.[177] His contributions include the "successful invention of Christian Latin hymnody",[178] while the hymnologist Guido Maria Dreves designated him to be "The Father of church hymnody".[179] He was not the first to write Latin hymns; the Bishop Hilary of Poitiers had done so a few decades before.[177] However, the hymns of Hilary are thought to have been largely inaccessible because of their complexity and length.[177][180] Only fragments of hymns from Hilary's Liber hymnorum exist, making those of Ambrose the earliest extant complete Latin hymns.[180] The assembling of Ambrose's surviving oeuvre remains controversial;[177][181] the almost immediate popularity of his style quickly prompted imitations, some which may even date from his lifetime.[182] There are four hymns for which Ambrose's authorship is universally accepted, as they are attributed to him by Augustine:[177]

- "Aeterne rerum conditor"

- "Deus creator omnium"

- "Iam surgit hora tertia"

- "Veni redemptor gentium" (also known as "Intende qui regis Israel")

Each of these hymns has eight four-line stanzas and is written in strict iambic tetrameter (that is 4 × 2 syllables, each iamb being two syllables). Marked by dignified simplicity, they served as a fruitful model for later times.[59] Scholars such as the theologian Brian P. Dunkle have argued for the authenticity of as many as thirteen other hymns,[181] while the musicologist James McKinnon contends that further attributions could include "perhaps some ten others".[177] Ambrose is traditionally credited but not actually known to have composed any of the repertory of Ambrosian chant also known simply as "antiphonal chant", a method of chanting where one side of the choir alternately responds to the other. However, Ambrosian chant was named in his honor due to his contributions to the music of the Church. With Augustine, Ambrose was traditionally credited with composing the hymn "Te Deum". Since the hymnologist Guido Maria Dreves in 1893, however, scholars have dismissed this attribution.[183]

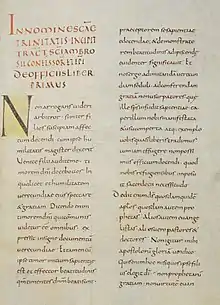

Writings

Source:[186][187] All works are originally in Latin. Following each is where it may be found in a standard compilation of Ambrose's writings. His first work was probably De paradiso (377–378).[188] Most have approximate dates, and works such as De Helia et ieiunio (377–391), Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam (377–389) and De officiis ministrorum (377–391) have been given a wide variety of datings by scholars.[lower-alpha 7] His best known work is probably De officiis ministrorum (377–391),[185] while the Exameron (386–390) and De obitu Theodosii (395) are among his most noted works.[188][2] In matters of exegesis he is, like Hilary, an Alexandrian. In dogma he follows Basil of Caesarea and other Greek authors, but nevertheless gives a distinctly Western cast to the speculations of which he treats. This is particularly manifest in the weightier emphasis which he lays upon human sin and divine grace, and in the place which he assigns to faith in the individual Christian life.[59] There has been debate on the attribution of some writings: for example De mysteriis is usually attributed to Ambrose, while the related De sacramentis is written in a different style with some silent disagreements, so there is less consensus over its author.[189]

Exegesis

- Exameron [The Six Days of Creation]. Vol. 6 books. 386–390. (PL, 14.133–288; CSEL, 32.1.3–261; FC, 42.3–283)

- De paradiso [On Paradise]. 377–378. (PL, 14.291–332; CSEL, 32.1.265–336; FC, 42.287–356)

- De Cain et Abet [On Cain and Abel]. 377–378. (PL, 14.333–80; CSEL, 32.1.339–409; FC, 42.359–437)

- De Noe [On Noah]. 378–384. (PL, 14.381–438; CSEL, 32.1.413–97)

- De Abraham [On Abraham]. Vol. 2 books. 380s. (PL, 14.441–524; CSEL, 32.1.501–638)

- De Isaac et anima [On Isaac and the Soul]. 387–391. (PL, 14.527–60; CSEL, 32.1.641–700; FC, 65.9–65.)

- De bono mortis [On the Good of Death]. 390. (PL, 14.567–96; CSEL, 32.1.707–53; FC, 65.70–113)

- De fuga saeculi [On Flight from the World]. 391–394. (PL, 14.597–624; CSEL, 32.2.163–207; FC, 65.281–323)

- De Iacob et vita beata [On Iacob and the Happy Life]. 386–388. (PL, 14.627–70; CSEL, 32.2.3–70; FC, 65.119–84)

- De Joseph [On Joseph]. 387–388. (PL, 14.673–704; CSEL, 32.2.73–122; FC, 65.187–237)

- De patriarchis [On the Patriarchs]. 391. (PL, 14.707–28; CSEL, 32.2.125–60; FC, 65.243–75)

- De Helia et ieiunio [On Elijah and Fasting]. 377–391. (PL, 14.731–64; CSEL, 32.2.411–65)

- De Nabuthae [On Naboth]. 389. (CSEL, 32.2.469)

- De Tobia [On Tobias]. 376–390. (PL, 14.797–832; CSEL, 32.2.519–573)

- De interpellatione Iob et David [The Prayer of Job and David]. Vol. 4 books. 383–394. (PL, 14.835–90; CSEL, 32.2.211–96; FC, 65.329–420)

- Apologia prophetae David [A Defense of the Prophet David]. 387. (PL, 14.891–926; CSEL, 32.2.299–355)

- Enarrationes in xii psalmos davidicos [Explanations of Twelve Psalms of David]. (PL, 14.963–1238; CSEL, 64)

- Expositio in Psalmum cxviii [A Commentary on Psalm 118]. 386–390. (PL, 15.1197–1526; CSEL, 62)

- Expositio Esaiae prophetae [A Commentary on the Prophet Isaiah]. (CCSL, 14.405–8)

- Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam [A Commentary on the Gospel according to Luke]. Vol. 10 books. 377–389. (PL, 15.1527–1850; CSEL, 32.4; CCSL, 14.1–400)

Moral and ascetical commentary

- De officiis ministrorum [On the Duties of Ministers]. 377–391. (PL, 16.25–194)

- De virginibus [On Virgins]. 377.

- De viduis [On Widows]. 377. (PL, 16.247–76)

- De virginitate [On Virginity]. 378. (PL, 16.279–316)

- De institutione virginis [An Instruction for a Virgin]. 391–392. (PL, 16.319–43)

- Exhortatio virginitatis [In Praise of Virginity]. 393–395. (PL, 16.351–80)

Dogmatic writings

- De fide [On the Faith]. Vol. 5 books. 378–380. (PL, 16.549–726; CSEL, 78)

- De Spiritu Sancto [On the Holy Spirit]. 381. (PL, 16.731–850; CSEL, 79.15–222; FC, 44.35–214)

- De incarnationis dominicae sacramento [On the Sacrament of the Lord's Incarnation]. 381–382. (PL, 16.853–84; CSEL, 79.223–81; FC, 44.219–62)

- Explanatio symboli ad initiandos [An Explanation of the Creed for Those about to be Baptised]. PL, 17.1193–96; CSEL, 73.1–12)

- De sacramentis [On the Sacraments]. Vol. 6 books. 390. (PL, 16.435–82; CSEL, 73.13–116; FC, 44.269–328)

- De mysteriis [On the Mysteries].

- De paenitentia [On Repentance]. 384–394. (PL, 16.485–546; CSEL, 73.117–206)

- Expositio fidei [An Explanation of the Faith]. (PL, 16.847–50)

- De sacramento regenerationis sive de philosophia [On the Sacrament of Regeneration, or On Philosophy]. (fragmented; CSEL, 11.131)

Sermons

- De excessu fratris [On the Death of his Brother]. 375–378. (PL, 16.1345–1414; CSEL, 73.207–325; FC, 22.161–259)

- De obitu Valentiniani [On the Death of Valentinian]. (PL, 16.1417–44; CSEL, 73.327–67; FC, 22.265–99)

- De obitu Theodosii [On the Death of Theodosius]. 25 February 395. (PL, 16.1447–88; CSEL, 73.369–401; FC, 22.307–332)

- Contra Auxentium de basilicis tradendis [Against Auxentius on Handing over the Basilicas]. 386. (PL, 16.1049–53)

Others

- 91 letters

- Ambrosiaster or the "pseudo-Ambrose" is a brief commentary on Paul's Epistles, which was long attributed to Ambrose.

Editions

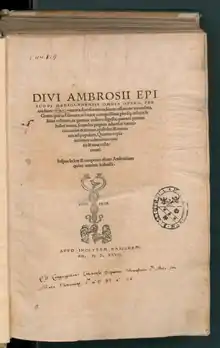

The history of the editions of the works of St. Ambrose is a long one. Erasmus edited them in four tomes at Basle (1527). A valuable Roman edition was brought out in 1580, in five volumes, the result of many years' labour; it was begun by Sixtus V, while yet the monk Felice Peretti. Prefixed to it is the life of St. Ambrose composed by Baronius for his Annales Ecclesiastici. The excellent Maurist edition of du Frische and Le Nourry appeared at Paris (1686–90) in two folio volumes; it was twice reprinted at Venice (1748–51, and 1781–82). The latest edition of the writings of St. Ambrose is that of Paolo Angelo Ballerini (Milan, 1878) in six folio volumes.

Standard editions

- Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. (1845). Patrologia Latina (in Latin). Vol. 14–17. Paris. Based on the Maurist edition published in Paris by Jacques Du Frische and Denis-Nicolas Le Nourry.

- Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum (in Latin). Vol. 11, 32, 62, 64, 73, 78–79. Vienna: Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna. 1866.

- Ballerini, P. A., ed. (1875–1883). Opera omnia (in Latin). Milan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Based on the Maurist edition published in Paris by Jacques Du Frische and Denis-Nicolas Le Nourry. - Catholic University of America, ed. (1947). Fathers of the Church. Vol. 22, 42, 44, 65. Washington DC.: Catholic University of America Press. OCLC 8110481.

- Corpus Christianorum. Vol. 14. Turnhout: Brepols. 1953. OCLC 1565173.

Latin

- Hexameron, De paradiso, De Cain, De Noe, De Abraham, De Isaac, De bono mortis – ed. C. Schenkl 1896, Vol. 32/1 (In Latin)

- De Iacob, De Ioseph, De patriarchis, De fuga saeculi, De interpellatione Iob et David, De apologia prophetae David, De Helia, De Nabuthae, De Tobia – ed. C. Schenkl 1897, Vol. 32/2

- Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam – ed. C. Schenkl 1902, Vol. 32/4

- Expositio de psalmo CXVIII – ed. M. Petschenig 1913, Vol. 62; editio altera supplementis aucta – cur. M. Zelzer 1999

- Explanatio super psalmos XII – ed. M. Petschenig 1919, Vol. 64; editio altera supplementis aucta – cur. M. Zelzer 1999

- Explanatio symboli, De sacramentis, De mysteriis, De paenitentia, De excessu fratris Satyri, De obitu Valentiniani, De obitu Theodosii – ed. Otto Faller 1955, Vol. 73

- De fide ad Gratianum Augustum – ed. Otto Faller 1962, Vol. 78

- De spiritu sancto, De incarnationis dominicae sacramento – ed. Otto Faller 1964, Vol. 79

- Epistulae et acta – ed. Otto Faller (Vol. 82/1: lib. 1–6, 1968); Otto Faller, M. Zelzer ( Vol. 82/2: lib. 7–9, 1982); M. Zelzer ( Vol. 82/3: lib. 10, epp. extra collectionem. gesta concilii Aquileiensis, 1990); Indices et addenda – comp. M. Zelzer, 1996, Vol. 82/4

English

- H. Wace and P. Schaff, eds, A Select Library of Nicene and Post–Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, 2nd ser., x [Contains translations of De Officiis (under the title De Officiis Ministrorum), De Spiritu Sancto (On the Holy Spirit), De excessu fratris Satyri (On the Decease of His Brother Satyrus), Exposition of the Christian Faith, De mysteriis (Concerning Mysteries), De paenitentia (Concerning Repentance), De virginibus (Concerning Virgins), De viduis (Concerning Widows), and a selection of letters]

- St. Ambrose "On the mysteries" and the treatise on the sacraments by an unknown author, translated by T Thompson, (London: SPCK, 1919) [translations of De sacramentis and De mysteriis; rev edn published 1950]

- S. Ambrosii De Nabuthae: a commentary, translated by Martin McGuire, (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America, 1927) [translation of On Naboth]

- S. Ambrosii De Helia et ieiunio: a commentary, with an introduction and translation, Sister Mary Joseph Aloysius Buck, (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America, 1929) [translation of On Elijah and Fasting]

- S. Ambrosii De Tobia: a commentary, with an introduction and translation, Lois Miles Zucker, (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America, 1933) [translation of On Tobit]

- Funeral orations, translated by LP McCauley et al., Fathers of the Church vol 22, (New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc., 1953) [by Gregory of Nazianzus and Ambrose],

- Letters, translated by Mary Melchior Beyenka, Fathers of the Church, vol 26, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 1954) [Translation of letters 1–91]

- Saint Ambrose on the sacraments, edited by Henry Chadwick, Studies in Eucharistic faith and practice 5, (London: AR Mowbray, 1960)

- Hexameron, Paradise, and Cain and Abel, translated by John J Savage, Fathers of the Church, vol 42, (New York: Fathers of the Church, 1961) [contains translations of Hexameron, De paradise, and De Cain et Abel]

- Saint Ambrose: theological and dogmatic works, translated by Roy J. Deferrari, Fathers of the church vol 44, (Washington: Catholic University of American Press, 1963) [Contains translations of The mysteries, (De mysteriis) The holy spirit, (De Spiritu Sancto), The sacrament of the incarnation of Our Lord, (De incarnationis Dominicae sacramento), and The sacraments]

- Seven exegetical works, translated by Michael McHugh, Fathers of the Church, vol 65, (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1972) [Contains translations of Isaac, or the soul, (De Isaac vel anima), Death as a good, (De bono mortis), Jacob and the happy life, (De Iacob et vita beata), Joseph, (De Ioseph), The patriarchs, (De patriarchis), Flight from the world, (De fuga saeculi), The prayer of Job and David, (De interpellatione Iob et David).]

- Homilies of Saint Ambrose on Psalm 118, translated by Íde Ní Riain, (Dublin: Halcyon Press, 1998) [translation of part of Explanatio psalmorum]

- Ambrosian hymns, translated by Charles Kraszewski, (Lehman, PA: Libella Veritatis, 1999)

- Commentary of Saint Ambrose on twelve psalms, translated by Íde M. Ní Riain, (Dublin: Halcyon Press, 2000) [translations of Explanatio psalmorum on Psalms 1, 35–40, 43, 45, 47–49]

- On Abraham, translated by Theodosia Tomkinson, (Etna, CA: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 2000) [translation of De Abraham]

- De officiis, edited with an introduction, translation, and commentary by Ivor J Davidson, 2 vols, (Oxford: OUP, 2001) [contains both Latin and English text]

- Commentary of Saint Ambrose on the Gospel according to Saint Luke, translated by Íde M. Ní Riain, (Dublin: Halcyon, 2001) [translation of Expositio evangelii secundum Lucam]

- Ambrose of Milan: political letters and speeches, translated with an introduction and notes by JHWG Liebschuetz, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005) [contains Book Ten of Ambrose's Letters, including the oration on the death of Theodosius I; Letters outside the Collection (Epistulae extra collectionem); Letter 30 to Magnus Maximus; The oration on the death of Valentinian II (De obitu Valentiniani).]

Several of Ambrose's works have recently been published in the bilingual Latin-German Fontes Christiani series (currently edited by Brepols).

See also

References

Notes

- Italian: Sant'Ambrogio [ˌsantamˈbrɔːdʒo]; Lombard: Sant Ambroeus [ˌsãːt ãˈbrøːs].

- "S. Paulinus in Vit. Ambr. 3 has the following: posito in administratione prefecture Galliarum patre eius Ambrosio natus est Ambrosius. From this, practically all of Ambrose's biographers have concluded that Ambrose's father was a praetorian prefect in Gaul. This is the only evidence we have, however, that there ever was an Ambrose as prefect in Gaul."[13]

- Two laws were recorded from this time. One of these canceled the "law of toleration" Gratian had previously issued at Sirmium. This toleration allowed freedom of worship to all with the exception of the heretical Manichaeans, Photinians and Eunomians.[49] The law canceling this has been presented in previous scholarship as proof of Ambrose' influence over Gratian, but the law's target was Donatism which had failed to be listed in the exceptions. There is no evidence to support Ambrose as having had anything to do with this restatement since sanctions against Donatism had existed since Constantine.[50]

- Recent scholarship has tended to reject former views that the edict was a key step in establishing Christianity as the official religion of the empire, since it was aimed exclusively at Constantinople and seems to have gone largely unnoticed by contemporaries outside the capital.[69][70] Nonetheless, the edict is the first known secular Roman law to positively assert a religious orthodoxy.[68]

- These Christian sources have had great influence on perceptions of this period by creating an impression of overt and continuous conflict that has been assumed on an empire-wide scale, while archaeological evidence indicates that, outside of violent rhetoric, the decline of paganism away from the imperial court was relatively non-confrontational.[136][137][138][139]

- Romans claimed to be the most religious of peoples.[145] Their unique success in war, conquest, and the formation of an empire, was attributed to the empire maintaining good relations with the gods through proper reverence and worship practices.[146] This did not change once the empire 's official religion became Christianity.

- Though both Paredi 1964, pp. 436–440 and Ramsey 2002, pp. 55–64 give dates for most of Ambrose's writings, the dates from Ramsey are preferred, as the publication is more recent and the author is dating the works from the perspective of scholarly consensus, whereas in Paredi, the author offers dates based on his own research. Regardless, when Ramsey does not provide dates for a work, those of Paredi are used.

Citations

- "Saint Ambrose, in the Sacello di San Vittore in Ciel d'Oro". Artstor. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Brown 2021.

- Guiley 2001, p. 16.

- Sharkey & Weinandy 2009, p. 208.

- McKinnon 2001.

- Smith 2021, p. 5.

- Ramsey 2002, p. ix.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. ix–x, 1–2.

- Paredi 1964, pp. 442–443.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 44.

- Loughlin 1907.

- Greenslade 1956, p. 175.

- Paredi 1964, p. 380.

- Attwater & John 1993.

- Barnes 2011, pp. 45–46.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 44–46.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 46.

- Thornton 1879, p. 15.

- Grieve 1911, p. 798.

- Barnes 2011, p. 50.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 55–57.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 52.

- Santi Beati (in Italian), Italy

- Mediolanensis 2005, p. 6.

- Cvetković 2019, p. 49.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Loughlin, James Francis (1907). "St. Ambrose". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Loughlin, James Francis (1907). "St. Ambrose". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company. -

McSherry, James (2011). Outreach and Renewal: A First-millennium Legacy for the Third-millennium Church. Cistercian studies series, 236. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780879072360.

An accomplished orator and legal advocate, Ambrose was appointed to the Judicial Council by Probus, Praetorian Prefect of Italy.

- Sparavigna 2016, p. 2.

- Butler 1991, p. 407.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 57.

- Kaye 1853, p. 33.

- Kaye 1853, p. 5.

- Butler 1991, p. 408.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. 6–7: "By Ambrose's day [Arianism] was in slow decline but far from having breathed its last: Ambrose's struggles with it occupied his energies for more than half of his term as bishop."

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 37.

- Compare: Ramsey 2002, p. 7: "Nor, when speaking of religious controversy during this period, must one forget Judaism and paganism. Judaism, it appears now, was probably more attractive to many early Christians than scholars had previously realized, which helps to explain some of the virulence of the attacks on it by the Fathers. Paganism, for its part, may have become less appealing for various reasons, but it was not in the nature of things, or of human beings, that it would ever disappear entirely."

- Ramsey 2002, p. 6: "[...] the history of the early Church [...] was [...] a golden age of religious ferment and controversy such as - it could well be argued - would not be seen again until the Reformation, more than a millennium later.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. 7–8: "In the face of all these rivals orthodox Christianity was not an impassive object. In reacting to them it defined itself and assumed more and more of the contours that we recognize today."

- Ramsey 2002, p. 5: "The task that lay before the Christian leadership was [...] to replace one form of the sacred with another. The fourth century was above all the moment when this replacement was being orchestrated, and the role that Ambrose played in the process was crucial.

- McLynn 1994, p. 79.

- Nicholson 2018, p. xv.

- Salzman, Sághy & Testa 2016, p. 2.

- McLynn 1994, p. 79–80.

- McLynn 1994, p. 80.

- McLynn 1994, p. 79–80, 87.

- McLynn 1994, p. 80,90;105.

- McLynn 1994, p. 90.

- McLynn 1994, p. 98.

- McLynn 1994, p. 91.

- McLynn 1994, p. 100-102.

- McLynn 1994, p. 103-105.

- McLynn 1994, p. 98-99.

- Trout 1999, p. 50.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 68.

- McLynn 1994, p. 104.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, p. 129.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, pp. 129–130.

- Lietzmann 1951, pp. 79–80.

- Grieve 1911, p. 799.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 80.

- CAH 1998, p. 106.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, p. 130.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, p. 131.

- Verlag 1976, pp. 235–244.

- McLynn 1994, p. 106-110.

- McLynn 1994, p. 108.

- McLynn 1994, p. 109.

- Errington 2006, p. 217.

- Errington 1997, pp. 410–415.

- Hebblewhite, p. 82.

- Sáry 2019, p. 73.

- Sáry 2019, pp. 72–74, fn. 32, 33, 34, 77.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, p. 17.

- Chesnut 1981, p. 245-252.

- Herrin 1987, p. 64.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, pp. 262.

- Liebeschuetz, Hill & Mediolanensis 2005, pp. 262–263.

- McLynn 1994, p. 331.

- Errington 1997, p. 425.

- Curran 1998, pp. 78–110.

- McLynn 1994, pp. 330–333.

- Hebblewhite 2020a, p. intro.

- McLynn 1994, p. 291.

- Cameron 2011, pp. 63, 64.

- Brown 1992, p. 111.

- Moorhead 2014, p. 3, 13.

- Cameron 2011, pp. 60, 63, 131.

- MacMullen 1984, p. 100.

- Washburn 2006, p. 215.

- McLynn 1994, pp. 291–292, 330–333.

- Cameron 2011, pp. 63–64.

- Errington 1997, p. 409.

- Cameron 2011, p. 74 (and note 177).

- Nicholson 2018, pp. 1482, 1484.

- Errington 2006, pp. 248–249.

- Cameron 2011, p. 74.

- Hebblewhite, chapter 8.

- McLynn 1994, p. 292.

- "Saint Ambrose, Bishop and Confessor, Doctor of the Church. December 7. Rev. Alban Butler. 1866. Volume XII: December. The Lives of the Saints". www.bartleby.com. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Norwich 1989, p. 116.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- Smith 2021, pp. 3–4.

- Mediolanensis 2005, pp. 4–5.

- Mediolanensis 2005, p. 5.

- Mediolanensis 2005, p. 4.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. ix–x.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 1.

- Davidson 1995, p. 315.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 9.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. 5–6.

- Smith 2021, p. 2.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 6.

- Smith 2021, p. 1.

- Brown 2012, p. 124.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 2.

- Smith 2021, pp. 6–7.

- Brown 2003, p. 80.

- Kempf 1980, p. 88.

- Brown 2012, p. 146.

- Elliott 2019, p. 27.

- Lee 2013, p. 41.

- Elliott 2019, p. 28.

- Nirenberg 2013, pp. 117–118.

- MacCulloch 2010, p. 300.

- McLynn 1994, pp. 308–9.

- Elliott 2019, p. 29.

- Elliott 2019, p. 23.

- Elliott 2019, p. 23, 49.

- Elliott 2019, p. 26.

- Elliott 2019, p. 30.

- Elliott 2019, p. 31.

- Salzman 1993, p. 375.

- Hagendahl 1967, pp. 601–630.

- North, John (2017). "The Religious History of the Roman Empire". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.114. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Bayliss, pp. 65, 68.

- Salzman, Sághy & Testa 2016, p. 7.

- Cameron 1991, pp. 121–124.

- Trombley 2001, pp. 166–168, Vol I; Trombley 2001, pp. 335–336, Vol II.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 69.

- Sheridan 1966, p. 187.

- Ambrose Epistles 17-18; Symmachus Relationes 1-3.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 76.

- Lietzmann 1951, pp. 76, 77.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1997). The nature of the gods; and, On divination. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-180-0. 2.8

- Sherk, Robert K. (1984). Rome and the Greek East to the Death of Augustus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-55268-7. doc. 8, 9–10.

- Lietzmann 1951, p. 77.

- Salzman 2006, p. 362.

- Lietzmann 1951, pp. 77–78.

- McLynn 1994, pp. 344–346.

- Cameron 2011, pp. 74–80.

- Augustine of Hippo, Epistle to Januarius, II, section 18

- Augustine of Hippo, Epistle to Casualanus, XXXVI, section 32

- Hanson, JW (1899). "18. Additional Authorities". Universalism: The Prevailing Doctrine of The Christian Church During Its First Five Hundred Years. Boston and Chicago: Universalist Publishing House. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- The Church Fathers on Universalism, Tentmaker, retrieved 5 December 2007

- Ambrose (1907), "Exposition of the Christian Faith, Book III", The Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Co, retrieved 24 February 2009 from New Advent.

- Davidson 1995, p. 312.

- Smith 2021, pp. 205–210.

- Davidson 1995, p. 313.

- Smith 2021, pp. 210–212.

- Brown 2012, p. 147.

- Wojcieszak 2014, pp. 177–187.

- Brown 2012, p. 133.

- Smith 2021, pp. 214, 216.

- ""St. Ambrose", Catholic Communications, Sydney Archdiocese". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Ambrose of Milan CSEL 64, 139

- Ambrose of Milan, De Mysteriis, 59, pp. 16, 410

- "NPNF2-10. Ambrose: Selected Works and Letters – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Ambrose of Milan, Expositio in Lucam 2, 17; PL 15, 1640

- De virginibus (On Virgins); De virginitate

- Schaff (ed.), Letter of Basil to Ambrose, Christian Classics Ethereal library, retrieved 8 December 2012

- Augustine. Confessions Book Six, Chapter Three.

- Gafford II 2015, pp. 20–21.

- Fenton, James (28 July 2006). "Read my lips". The Guardian. London.

- Gavrilov 1997, p. 56–73, esp. 70–71.

- Burnyeat 1997, pp. 74–76.

- McKinnon 2001, § para. 4.

- Cunningham 1955, p. 509.

- Dunkle 2016, p. 1.

- Boynton 2001, "1. History of the repertory".

- Dunkle 2016, p. 11.

- Dunkle 2016, pp. 3–4.

- McKinnon 2001, § para. 2.

- "Ambrose, De officiis ministrorum". e-codices.unifr.ch. swissuniversities. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 60.

- Paredi 1964, pp. 436–440.

- Ramsey 2002, pp. 55–64.

- Ramsey 2002, p. 56.

- St. Ambrose "On the mysteries" and the treatise "On the sacraments" by an unknown author, archive.org

Works cited

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1993), The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.), New York: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-051312-7

- Barnes, T. D. (2011). "The Election of Ambrose of Milan". In Leemans, Johan; Nuffelen, Peter Van; Keough, Shawn W.J.; Nicolaye, Carla (eds.). Episcopal Elections in Late Antiquity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-026860-7.

- Bayliss, Richard (2004). Provincial Cilicia and the Archaeology of Temple Conversion. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 1-84171-634-0.

- Boynton, Susan (2001). "Hymn: II. Monophonic Latin". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.13648. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Brown, Peter (1998). Late antiquity (illustrated reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51170-5.

- Brown, Peter (1992). Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-13340-0.

- Brown, Peter (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom, Triumph and Diversity, AD 200-1000. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-118-30126-5.

- Brown, Peter (2012). Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15290-5.

- Brown, Peter (1 January 2021). "St. Ambrose". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- Burnyeat, MF (1997). "Postscript on silent reading". Classical Quarterly. 47 (1): 74–76. doi:10.1093/cq/47.1.74. JSTOR 639598.

- Butler, Alban (1991). Walsh, Michael (ed.). Butler's lives of the saints. [San Francisco]. ISBN 978-0-06-069299-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter, eds. (1998). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. XIII. Vol. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-30200-5.

- Cameron, Averil (1991). Christianity and the rhetoric of empire : the development of Christian discourse. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08923-5.

- Cameron, Alan (2011). The Last Pagans of Rome. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974727-6.

- Chesnut, Glenn F. (1981). "The Date of Composition of Theodoret's Church history". Vigiliae Christianae. 35 (3): 245–252. doi:10.2307/1583142. JSTOR 1583142.

- Cunningham, Maurice P. (October 1955). "The Place of the Hymns of St. Ambrose in the Latin Poetic Tradition". Studies in Philology. 52 (4): 509–514. JSTOR 4173143.

- Curran, John (1998). "From Jovian to Theodosius". In Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. XIII (Second ed.). Cambridge [England]. ISBN 978-0-521-30200-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cvetković, Carmen Angela; Gemeinhardt, Peter, eds. (2019). Episcopal Networks in Late Antiquity: Connection and Communication Across Boundaries. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-055339-0.

- Davidson, Ivor J. (1995). "Ambrose's de officiis and the Intellectual Climate of the Late Fourth Century". Vigiliae Christianae. 49 (4): 313–333. doi:10.1163/157007295X00086. JSTOR 1583823.

- Dunkle, Brian P. (2016). Enchantment and Creed in the Hymns of Ambrose of Milan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198788225.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-878822-5.

- Elliott, Paul M. C. (2019). Creation and Literary Re-Creation: Ambrose's Use of Philo in the Hexaemeral Letters. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-4087-5.

- Errington, R. Malcolm (1997). "Christian Accounts of the Religious Legislation of Theodosius I". Klio. 79 (2): 398–443. doi:10.1524/klio.1997.79.2.398. S2CID 159619838.

- Errington, R. Malcolm (2006). Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3038-0.

- Gafford II, Joe Aaron (2015). "The Life and Conversion of Augustine of Hippo". Tenor of Our Times. 4 (1).

- Gavrilov, AK (1997). "Techniques of Reading in Classical Antiquity". Classical Quarterly. 47 (1): 56–73. doi:10.1093/cq/47.1.56. JSTOR 639597.

- Greenslade, Stanley Lawrence (1956). Early Latin theology: selections from Tertullian, Cyprian, Ambrose, and Jerome. Library of Christian classics. Vol. 5. Westminster Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22005-1.

- Grieve, Alexander J. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 798–799.

- Guiley, Rosemary (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. New York: Facts On File, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4381-3026-2.

- Hagendahl, Harald (1967). Augustine and the Latin Classics, vol. 2: Augustine's Attitude, Studia Graeca et Latina Gothoburgensia. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Hebblewhite, Mark (2020). Theodosius and the Limits of Empire. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315103334. ISBN 978-1-138-10298-9. S2CID 213344890.

- Hebblewhite, Mark (2020a). Theodosius and the Limits of Empire (illustrated ed.). Routledge. pp. intro. ISBN 978-1-351-59476-9.

- Herrin, Judith (1987). The Formation of Western Christendom. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00831-8.

- Kaye, John (1853). Some account of the Council of Nicæa in connexion with the life of Athanasius. F. J. Rivington.

- Kempf, Friedrich (1980). Dolan, John Patrick; Jedin, Hubert (eds.). The Church in the Age of Feudalism. Vol. 3. Burns & Oates. ISBN 978-0-86012-085-8.

- Lee, A. D. (2013). From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-6835-9.

- Liebeschuetz, John Hugo Wolfgang Gideon; Hill, Carole; Mediolanensis, Ambrosius (2005). Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches (illustrated, reprint ed.). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-829-4.

- Lietzmann, Hans (1951). The Era of the Church Fathers. Vol. 4. Translated by Bertram Lee Woolf. London: Lutterworth Press. doi:10.1515/9783112335383. ISBN 978-3-11-233538-3.

- Loughlin, James (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2010). Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-18999-3.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1984). Christianizing the Roman Empire: (A.D. 100-400). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03642-8.

- McKinnon, James W. (November 1994). "Desert Monasticism and the Later Fourth-Century Psalmodic Movement". Music & Letters. 75 (4): 505–521. doi:10.1093/ml/75.4.505. JSTOR 737286.

- McKinnon, James W. (2001). "Ambrose". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.00751. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- McLynn, Neil B. (1994), Ambrose of Milan: Church and Court in a Christian Capital, The Transformation of the Classical Heritage, vol. 22, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-08461-2

- Mediolanensis, Ambrose (2005). Liebeschuetz, J. H. W. G.; Hill, Carole (eds.). Ambrose of Milan: Political Letters and Speeches. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-829-4.

- Moorhead, John (2014). Ambrose: Church and Society in the Late Roman World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-89102-4.

- Nicholson, Oliver, ed. (2018). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-174445-7.

- Nirenberg, David (2013). Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78185-296-5.

- Norwich, John Julius (1989). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Guild Publishing. ISBN 9780670802517.

- Paredi, Angelo (1964), Saint Ambrose: His Life and Times, translated by Joseph Costelloe, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 978-0-268-00239-8

- Ramsey, Boniface (2002) [1997]. Ambrose. The Early Church Fathers. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81504-3.

- Salzman, Michele Renee (1993). "The Evidence for the Conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity in Book 16 of the "Theodosian Code"". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 42 (3): 362–378. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4436297.

- Salzman, Michele Renee (2006). "Symmachus and the "Barbarian" Generals". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 55 (3).

- Salzman, Michele; Sághy, Marianne; Testa, Rita (2016). Pagans and Christians in late antique Rome : conflict, competition, and coexistence in the fourth century. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-107-11030-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sáry, Pál (2019). "Remarks on the Edict of Thessalonica of 380". In Vojtech Vladár (ed.). Perpauca Terrena Blande Honori dedicata pocta Petrovi Blahovi K Nedožitým 80. Narodeninám. Trnavská univerzity. pp. 67–80. ISBN 978-80-568-0313-4.

- Sharkey, Michael; Weinandy, Thomas, eds. (1 January 2009). International Theological Commission. Vol. II: Texts and Documents, 1986–2007. Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-1-58617-226-8.

- Sheridan, J.J. (1966). "The Altar of Victory – Paganism's Last Battle". L'Antiquité Classique. 35 (1): 186–206. doi:10.3406/antiq.1966.1466.