Temperance (virtue)

Temperance in its modern use is defined as moderation or voluntary self-restraint.[1] It is typically described in terms of what a person voluntarily refrains from doing.[2] This includes restraint from revenge by practicing mercy and forgiveness, restraint from arrogance by practicing humility and modesty, restraint from excesses such as extravagant luxury or splurging, restraint from overindulgence in food and drink, and restraint from rage or craving by practicing calmness and equanimity.[2]

The distinction between temperance and self-control is subtle. A person who exhibits self-control wisely refrains from giving in to unwise desires. A person who exhibits temperance does not have unwise desires in the first place because they have wisely shaped their character in such a way that their desires are proper ones. Aristotle suggested this analogy: An intemperate person is like a city with bad laws; a person who lacks self control is like a city that has good laws on the books but doesn’t enforce them.[3]: VII.10

Temperance has been described as a virtue by religious thinkers, philosophers, and more recently, psychologists, particularly in the positive psychology movement. It has a long history in philosophical and religious thought.

It is generally characterized as the control over excess, and expressed through characteristics such as chastity, modesty, humility, self-regulation, hospitality, decorum, abstinence, and forgiveness; each of these involves restraining an excess of some impulse, such as sexual desire, vanity, or anger.

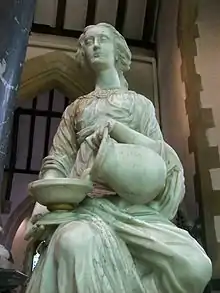

In classical iconography, the virtue is often depicted as a woman holding two vessels transferring water from one to another. It is one of the cardinal virtues in western thought, and is found in Greek philosophy and Christianity, as well as in Eastern traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism.

Temperance is one of the six virtues in the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths, along with wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, and transcendence.[4]

The term "temperance" can also refer to the abstention from alcohol (teetotalism), especially with reference to the temperance movement. It can also refer to alcohol moderation.

Philosophical perspectives

Greek civilization

There are two words in ancient Greek that have been translated to "temperance" in English. The first, sôphrosune, largely meant "self-restraint". The other, enkrateia', was a word coined during the time of Aristotle, to mean "control over oneself", or "self-discipline". Enkrateia appears three times in the Bible, where it was translated as "temperance" in the King James translation.

The modern meaning of temperance has evolved since its first usage. In Latin, tempero means restraint (from force or anger), but also more broadly the proper balancing or mixing (particularly, of temperature, or compounds). Hence the phrase "to temper a sword", meaning the heating and cooling process of forging a metal blade. The Latin also referred to governing and control, likely in a moderate way (i.e. not with the use of excessive force).

Temperance is a major Athenian virtue, as advocated by Plato; self-restraint (sôphrosune) is one of his four core virtues of the ideal city. In "Charmides", one of Plato's early dialogues, an attempt is made to describe temperance, but fails to reach an adequate definition.

Aristotle

Aristotle included discussions of both temperance[3]: III.10–11 and self-control[3]: VII.1–10 in his pioneering system of virtue ethics.

Aristotle restricts the sphere of temperance to bodily pleasures, and defines temperance as "a mean with regard to pleasures,"[3]: III.10 distinct from self-indulgence. Like courage, temperance is a virtue concerning our discipline of "the irrational parts of our nature" (fear, in the case of courage; desire, in the case of temperance).[3]: III.10

His discussion is found in the Nicomachean Ethics Book III, chapters 10–12, and concludes in this way:

And so the appetites of the temperate man should be in harmony with his reason; for the aim of both is that which is noble: the temperate man desires what he ought, and as he ought, and when he ought; and this again is what reason prescribes. This, then, may be taken as an account of temperance.[3]: III.12

As with virtue generally, temperance is a sort of habit, acquired by practice.[3]: II.1 It is a state of character, not a passion or a faculty,[3]: II.5 specifically a disposition to choose the mean[3]: II.6 between excess and defecit.[3]: II.2 The mean is hard to attain, and is grasped by perception, not by reasoning.[3]: II.9

Pleasure in doing virtuous acts is a sign that one has attained a virtuous disposition.[3]: II.3 Temperance is the alignment of our desires with our enlightened self-interest, such that we desire to do what is best for our own flourishing.

The word Aristotle used for "intemperate" (ἀκόλαστος) was the Greek word for "unchastened"[3]: III.12, f68 — the implication being that the intemperate person is immature and undisciplined and has not yet learned how to live well.

Marcus Aurelius

In his Meditations, the Roman emperor and stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius defines temperance as "a virtue opposed to love of pleasure".[5]: VIII.39 He argues that temperance separates humans from animals, writing that:

[I]t is the peculiar office of the rational and intelligent motion to circumscribe itself, and never to be overpowered either by the motion of the senses or the appetites, for both are animal; but the intelligent motion claims superiority and does not permit itself to be overpowered by the others.[5]: VII.55

For Marcus, this rational faculty exists to understand the appetites, rather than be used by them. In the ninth book of the Meditations, he gives this advice: "Wipe out imagination: check desire: extinguish appetite: keep the ruling faculty in its own power."[5]: IX.7

Marcus takes inspiration from his father, someone Marcus remembers as "satisfied on all occasions", who "showed sobriety in all things" and "did not take the bath at unseasonable hours; he was not fond of building houses, nor curious about what he ate, nor about the texture and colour of his clothes, nor about the beauty of his slaves." Marcus writes that temperance is both difficult and yet important. He favourably likens his father to Socrates, in that "he was able both to abstain from, and to enjoy, those things which many are too weak to abstain from, and cannot enjoy without excess. But to be strong enough both to bear the one and to be sober in the other is the mark of a man who has a perfect and invincible soul".[5]: I.16–17

Thomas Aquinas

In his Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas defines the scope of temperance: "Temperance... considered as a human virtue, deals with the desires of sensible pleasures".[6]: I.Q59 He refines 'sensible pleasure' by stating, "the object of temperance is a good in respect of the pleasures connected with the concupiscence of touch."[6]: I–II.Q63 He further defines temperance by associating it with the forbearing of sensible pleasures, as opposed to the mere toleration of sensible pain, a distinction he highlights when he claims that "the temperate man is praised for refraining from pleasures of touch, more than for not shunning the pains which are contrary to them".[6]: I–II.Q35

For Aquinas, temperance need never contradict pleasure in itself: "The temperate man does not shun all pleasures, but those that are immoderate, and contrary to reason."[6]: I–II.Q34 For example, he discusses food and sex, which, when approached with temperance, fulfill human requirements for survival without contradicting the virtue of moderation:

Accordingly, if we take a good, and it be something discerned by the sense of touch, and something pertaining to the upkeep of human life either in the individual or in the species, such as the pleasures of the table or of sexual intercourse, it will belong to the virtue of temperance.[6]: I–II.Q60

Michel de Montaigne

Similarly to Marcus Aurelius, the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne writes in his essay 'Of Experience' that temperance enhances the soul:

Greatness of soul consists not so much in mounting and in pressing forward, as in knowing how to govern and circumscribe itself; it takes everything for great, that is enough, and demonstrates itself in preferring moderate to eminent things."[7]

Montaigne differs from Marcus in that Montaigne believes temperance enhances pleasure, rather than opposing the love of it: "Intemperance is the pest of pleasure; and temperance is not its scourge, but rather its seasoning."[7] Like Aquinas, Montaigne sees no contradiction between temperance and pleasure in the right moral context. Rather, he believes that "there is no pleasure so just and lawful, where intemperance and excess are not to be condemned."[8] For example, he commends a temperate approach to the pleasures of sex within marriage: "Marriage is a solemn and religious tie, and therefore the pleasure we extract from it should be a sober and serious delight, and mixed with a certain kind of gravity; it should be a sort of discreet and conscientious pleasure."[8] Montaigne also discusses the difficulty of temperance. He muses on whether pleasure's tempering creates unhappiness:

But, to speak the truth, is not man a most miserable creature the while? It is scarce, by his natural condition, in his power to taste one pleasure pure and entire; and yet must he be contriving doctrines and precepts to curtail that little he has; he is not yet wretched enough, unless by art and study he augment his own misery[.][8]

In his essay 'Of Drunkenness', Montaigne accepts that temperance neither can nor should completely exclude the possibility of desire: "’Tis sufficient for a man to curb and moderate his inclinations, for totally to suppress them is not in him to do."[9] But in 'Of Managing the Will', Montaigne warns against failing to curb inclinations: "The more we amplify our need and our possession, so much the more do we expose ourselves to the blows and adversities of Fortune."[10]

Francis Bacon

In his Advancement of Learning, the English philosopher Francis Bacon, like Marcus and Montaigne, recognizes the difficulty of adhering to temperance in the face of sensations and desires. He writes "that the mind in the nature thereof would be temperate and stayed, if the affections, as winds, did not put it into tumult and perturbation."[11]: XXII.6 He believes this problem applies especially to those fortunate enough to enjoy the security of material comfort. Of these, he says, "great and sudden fortune for the most part defeateth men" and quotes Psalms 62:10's advice that the wealthy ought to emotionally detach from their wealth.[11]: XXII.5

John Milton

In Paradise Lost, the English poet and revolutionary republican John Milton has the Archangel Michael expound on the value of temperance, or what he calls "the rule of not too much", a virtue he states has the benefit of conferring long life on the temperate person:

There is, said Michael, if thou well observe

The rule of not too much, by temperance taught

In what thou eatst and drinkst, seeking from thence

Due nourishment, not gluttonous delight,

Till many years over thy head return:

So maist thou live, till like ripe Fruit thou drop

Into thy Mothers lap, or be with ease

Gatherd, not harshly pluckt, for death mature[.][12]

However, like Marcus, Montaigne, and Bacon before him, Milton well-estimated the difficulty of attaining temperance. In his essay Areopagitica, he writes that temperance requires prudence in differentiating good desires from evil passions, but also that this prudence comes only from an understanding of temptation, a familiarity which could bring an intemperate person under the sway of evil appetites: "He that can apprehend and consider vice with all her baits and seeming pleasures, and yet abstain, and yet distinguish, and yet prefer that which is truly better, he is the true wayfaring Christian."[13]

Blaise Pascal

For the French philosopher Blaise Pascal, temperance respects the balance between the two extremities of insatiable desire and total lack thereof. Like Montaigne, Pascal believes it impossible to completely extinguish desire, as advocated by Marcus Aurelius, yet Pascal calls for a curbing of desire. As he writes in his Pensées, "Nature has set us so well in the centre, that if we change one side of the balance, we change the other also." For example, he calls for a balancing temperance in the acts of reading and of drinking wine: "When we read too fast or too slowly, we understand nothing"; "Too much and too little wine. Give him none, he cannot find truth; give him too much, the same."[14]

Immanuel Kant

In the first section of his Metaphysics of Morals, German philosopher Immanuel Kant explores temperance as the virtue of "Moderation in the affections and passions, self-control, and calm deliberation" and goes so far as to praise temperance as an essential and beneficial element of every human being's potential, even though he thinks ancient philosophers, which would include Marcus Aurelius, mostly accept the virtue as one requiring no qualification.[15] On the other hand, Kant qualifies temperance by warning it could increase the effectiveness of evil acts by the ill-intentioned: "For without the principles of a good will, [temperance] may become extremely bad, and the coolness of a villain not only makes him far more dangerous, but also directly makes him more abominable in our eyes than he would have been without it."[16] Thus, for Kant, temperance takes on its most important moral effects when it complements the other virtues.

In his Critique of Judgment, Kant writes that art and science, by sharpening rationality, assist the cultivation of temperance in the face of purely animal or sensual desire, or what he termed 'sense-propensions':

The beautiful arts and the sciences which, by their universally-communicable pleasure, and by the polish and refinement of society, make man more civilised, if not morally better, win us in large measure from the tyranny of sense-propensions, and thus prepare men for a lordship, in which Reason alone shall have authority[.][17]

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill writes about temperance in his book On Liberty. He supports laws against intemperate behavior and asks a rhetorical question:

If gambling, or drunkenness, or incontinence, or idleness, or uncleanliness, are as injurious to happiness, and as great a hindrance to improvement, as many or most of the acts prohibited by law, why (it may be asked) should not law, so far as is consistent with practicability and social convenience, endeavour to repress these also?[18]: 151–152

Mill also supports the cultivation of public opinion against intemperance:

And as a supplement to the unavoidable imperfections of law, ought not opinion at least to organise a powerful police against these vices, and visit rigidly with social penalties those who are known to practise them?[18]: 152

However, Mill advocates public punishment of intemperance, not of the kind affecting a person's close friends and family, but of the kind affecting society at large, and uses the example of a drunk police officer: "No person ought to be punished simply for being drunk; but a soldier or a policeman should be punished for being drunk on duty."[18]: 154

Charles Darwin

In his book The Descent of Man, the naturalist Charles Darwin expresses a strong belief in the human ability to cultivate temperance:

Man prompted by his conscience, will through long habit acquire such perfect self-command, that his desires and passions will at last yield instantly and without a struggle to his social sympathies and instincts, including his feeling for the judgment of his fellows. The still hungry, or the still revengeful man will not think of stealing food, or of wreaking his vengeance.[19]

Thus, for Darwin, humanity's sociability dictates a level of personal restraint, especially as practiced over time by the socialized person. Darwin also states his belief in the likelihood of temperance's transmittance from one generation to subsequent generations: "It is possible, or as we shall hereafter see, even probable, that the habit of self-command may, like other habits, be inherited."[19]

Religions

Themes of temperance can be seen across cultures and time.

Buddhism

Temperance is an essential part of the Noble Eightfold Path; "Right Effort", the sixth step on the path, includes indriya-samvara, translated as "guarding the sense doors" or "sense restraint". In the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, often regarded as the first teaching, the Buddha describes the Noble Eightfold Path as the Middle Way of moderation, between the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification. The third and fifth of the five precepts (pañca-sila) reflect values of temperance: "misconduct concerning sense pleasures" and drunkenness are to be avoided.[20]

Christianity

"Temperance is the moral virtue that moderates the attraction of pleasures and provides balance in the use of created goods."[21] The Old Testament emphasizes temperance as a core virtue, as evidenced in the Book of Proverbs. The New Testament does so as well, with forgiveness being central to theology and self-control being one of the Fruits of the Spirit.[22] With regard to Christian theology, the word temperance is used by the King James Version in Galatians 5:23 for the Greek word ἐγκρατεία (enkrateia), which means self-control or discipline.

Thomas Aquinas adopted Aristotle's set of virtues, which included temperance, and built his own scheme on those. He called temperance a "disposition of the mind which binds the passions".[22] Temperance is believed to combat the sin of gluttony.

Within Christianity, temperance is a virtue akin to self-control. It is applied to all areas of life. It can especially be viewed in practice among sects like the Amish, Old Order Mennonites, and Conservative Mennonites. Temperance is regarded as a virtue that moderates attraction and desire for pleasure and "provides balance in the use of created goods".

Hinduism

The concept of dama (Sanskrit: दम) in Hinduism is equivalent to temperance. It is sometimes written as damah (दमः).[23] The word dama, and Sanskrit derivative words based on it, connote self-control and self-restraint. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, in verse 5.2.3, states that three characteristics of a good, developed person are self-restraint (damah), compassion and love for all sentient life (daya), and charity (daana).[24] In Hinduism literature dedicated to yoga, self-restraint is expounded with the concept of yamas (Sanskrit: यम).[25] Self-restraint (dama) is one of the six cardinal virtues of ṣaṭsampad in jnana yoga.[26]

The list of virtues that constitute a moral life evolved in vedas and upanishads. Over time, new virtues were conceptualized and added, some replaced, others merged. For example, Manusamhita initially listed ten virtues necessary for a human being to live a dharmic (moral) life: dhriti (courage), kshama (forgiveness), Dama (temperance), asteya (Non-covetousness/Non-stealing), saucha (purity), indriyani-graha (control of senses), dhi (reflective prudence), vidya (wisdom), satyam (truthfulness), and akrodha (freedom from anger). In later verses, this list was reduced to five virtues by the same scholar, by merging and creating a more broader concept. The shorter list of virtues became: ahimsa (Non-violence), dama (temperance), asteya (Non-covetousness/Non-stealing), saucha (purity), and satyam (truthfulness).[27] This trend of evolving concepts continues in classical Sanskrit literature.[28]

Five types of self-restraints are considered essential for a moral and ethical life in Hindu philosophy: one must refrain from any violence that causes injury to others, refrain from starting or propagating deceit and falsehood, refrain from theft of other's property, refrain from sexually cheating on one's partner, and refrain from avarice.[25][29] The scope of self-restraint includes one's action, the words one speaks or writes, and one's thoughts. The necessity for temperance is explained as preventing bad karma which sooner or later haunts and returns to the unrestrained.[30] The theological need for self-restraint is also explained as reigning in the damaging effect of one's action on others, as hurting another is hurting oneself because all life is one.[29][31]

Jainism

Temperance in Jainism is deeply imbibed in its five major vows which are:

- Ahimsa (nonviolence)

- Satya (truth)

- Brahmacharya (chastity or celibacy),

- Asteya (non-stealing)

- Aparigraha (non-possessiveness).

In Jainism, the vow of ahimsa is not just restricted to not resorting to physical violence, but to violence in all forms either by thought, speech, or action.

On Samvatsari, the last day of Paryushan—the most prominent festival of Jainism—the Jains greet their friends and relatives on this last day with Micchāmi Dukkaḍaṃ, seeking their forgiveness. The phrase is also used by Jains throughout the year when a person makes a mistake, or recollects making one in everyday life, or when asking for forgiveness in advance for inadvertent ones.[32]

Contemporary organizations

The value of temperance is still promoted by more modern sources such as the Boy Scouts, William Bennett, and Ben Franklin.[4] Philosophy has contributed a number of lessons to the study of traits, particularly in its study of injunctions and its listing and organizing of virtues.

One set of positive psychology theorists defined temperance to include as facets these four main character strengths: forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation.[4]

See also

References

- Green, Joel (2011). Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic. p. 769. ISBN 978-0-8010-3406-0.

- Pulkkinen, Lea; Pitkänen, Tuuli (2012). "Temperance and the strengths of personality". In Schwarzer, Ralf (ed.). Personality, human development, and culture: international perspectives on psychological science. Vol. 2. Hove: Psychology. pp. 127–140. ISBN 978-0-415-65080-9.

- Aristotle (1906) [c. 340 BCE]. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Peters, F.H.

- Peterson, Christopher; Seligman, Martin E.P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. American Psychological Association / Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195167016.

- Marcus Aurelius (1889) [c. 180 CE]. Meditations. Translated by Long, George. The Internet Classics Archive.

- Aquinas, Thomas (1947) [1274]. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- de Montaigne, Michel (1877) [1580]. "Of Experience". In Hazlitt, William Carew (ed.). Essays. Vol. III. Translated by Cotton, Charles. Project Gutenberg.

- de Montaigne, Michel (1877) [1580]. "Of Moderation". In Hazlitt, William Carew (ed.). Essays. Vol. I. Translated by Cotton, Charles. Project Gutenberg.

- de Montaigne, Michel (1877) [1580]. "Of Drunkenness". In Hazlitt, William Carew (ed.). Essays. Vol. II. Translated by Cotton, Charles. Project Gutenberg.

- de Montaigne, Michel (1877) [1580]. "Of Managing the Will". In Hazlitt, William Carew (ed.). Essays. Vol. III. Translated by Cotton, Charles. Project Gutenberg.

- Bacon, Francis (1893) [1605]. Morley, Henry (ed.). Advancement of Learning. Vol. II. Cassell & Company.

- Milton, John. Paradise Lost. The John Milton Reading Room. XI:530–537.

- Milton, John (1644). Areopagitica. The John Milton Reading Room.

- Pascal, Blaise (1958) [1670]. "The Misery of Man without God". Pensées. Translated by Trotter, W.F. E.P. Dutton & Co. §II.70–71. ISBN 0-525-47018-2.

- Kant, Immanuel (2002) [1785]. "Transition from the Common Rational Knowledge of Morality to the Philosophical". Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by Abbott, Thomas Kingsmill. Project Gutenberg.

Moderation in the affections and passions, self-control, and calm deliberation are not only good in many respects, but even seem to constitute part of the intrinsic worth of the person; but they are far from deserving to be called good without qualification, although they have been so unconditionally praised by the ancients.

- Kant, Immanuel (2002) [1785]. "Transition from the Common Rational Knowledge of Morality to the Philosophical". Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by Abbott, Thomas Kingsmill. Project Gutenberg.

- Kant, Immanuel (2015) [1790]. "Of the ultimate purpose of nature as a teleological system". The Critique of Judgment. Translated by Bernard, J.H. Project Gutenberg.

- Mill, John Stuart (2011) [1859]. "Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual". On Liberty. Project Gutenberg.

- Darwin, Charles (2000) [1871]. "Comparison of the Mental Powers of Man and the Lower Animals". The Descent of Man. Project Gutenberg.

- Harvey, P. (1990). An introduction to Buddhism: Teaching, history and practices. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Standridge, Paula (November 17, 2018). "Virtue of temperance can offer life balance". Understanding Our Church – via Diocese of Little Rock.

- Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives on positive psychology (pp. 11–30). New York: Springer.

- "Sanskrit translations for Self-Control". English-Sanskrit Dictionary. Germany. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10.

- Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad. Translated by Mādhavānanda, Swāmi. Advaita Ashrama. 1950. p. 816.

तदेतत्त्रयँ शिक्षेद् दमं दानं दयामिति (Learn three cardinal virtues—temperance, charity, and compassion for all life.)

For discussion: pp. 814–821 - Lochtefeld, James (2002). "Yama (2)". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. New York: Rosen Publishing. p. 777. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1.

- "दम dama". Dictionnaire Héritage du Sanscrit (in French).

-

- Gupta, B. (2006). "Bhagavad Gītā as Duty and Virtue Ethics". Journal of Religious Ethics. 34 (3): 373–395.

- Mohapatra, Amulya; Mohapatra, Bijaya (1993). Hinduism: Analytical Study. Mittal Publications. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-81-7099-388-9.

-

- Tiwari, Kedar Nath (2014). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 33–34. ISBN 81-208-0294-2.

- Bailey, G. (1983). "Puranic notes: reflections on the myth of sukesin". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 6 (2): 46–61.

- Heim, M. (2005). "Differentiations in Hindu ethics". In Schweiker, William (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Religious Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 341–354. ISBN 0-631-21634-0.

-

- Rao, G. H. (1926). "The Basis of Hindu Ethics". International Journal of Ethics. 37: 19–35.

- Hindery, Roderick (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0866-5.

- Sturgess, Stephen; Kriyananda, Swami (2002). The Yoga Book: A Practical Guide to Self-realization. Watkins Publishing Limited. Chapter 2. ISBN 978-1-84293-034-2.

- Vijaya, M.R.P.; Jani, K.C. (1951). "Sthavirāvali". Śramana Bhagavān Mahāvira. Śri Jaina Siddhanta Society. p. 120.