Gotthard Pass

The Gotthard Pass or St. Gotthard Pass (Italian: Passo del San Gottardo; German: Gotthardpass) at 2,106 m (6,909 ft) is a mountain pass in the Alps traversing the Saint-Gotthard Massif and connecting northern Switzerland with southern Switzerland. The pass lies between Airolo in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino, and Andermatt in the German-speaking canton of Uri, and connects further Bellinzona and Lugano to Lucerne, Basel, and Zurich. The Gotthard Pass lies at the heart of the Gotthard, a major transport axis of Europe, and it is crossed by three traffic tunnels, each being the world's longest at the time of their construction: the Gotthard Rail Tunnel (1882), the Gotthard Road Tunnel (1980) and the Gotthard Base Tunnel (2016). With the Lötschberg to the west, the Gotthard is one of the two main north-south routes through the Swiss Alps.

| Gotthard Pass | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Passo del San Gottardo German: Gotthardpass | |

The area of the Gotthard Pass from the west | |

| Elevation | 2,106 m (6,909 ft) |

| Traversed by | National Road 2 Old paved road (Tremola) Gotthard Rail Tunnel Gotthard Road Tunnel Gotthard Base Tunnel |

| Location | Canton of Ticino, Switzerland (close to canton of Uri) |

| Range | Lepontine Alps |

| Coordinates | 46°33′22.5″N 8°34′04″E |

| Topo map | Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo |

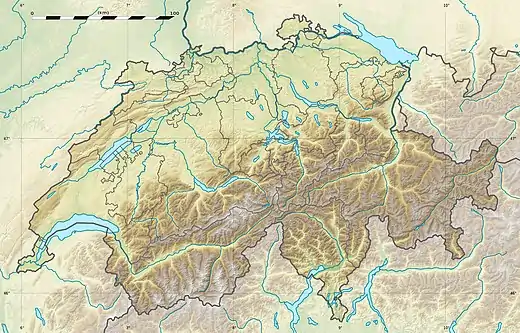

Location in Switzerland (see detailed map) | |

Since the Middle Ages, transit across the Gotthard played an important role in Swiss history, the region north of the Gotthard becoming the nucleus of the Swiss Confederacy in the 13th century, after the pass became a vital trade route between Northern and Southern Europe.[1] The Gotthard is sometimes referred to as the "King of Mountain Passes" because of its central and strategic location.[2][3]

Geography

The Gotthard Pass lies on the main watershed of the Gotthard massif, a massif lying at the heart of the Swiss Alps, between the cantons of Valais, Ticino, Grisons and Uri. The pass itself is the lowest point between the summits of Pizzo Lucendro (west) and Pizzo Centrale (east). It connects the cantons of Uri (north) and Ticino (south), its summit (2,106 metres (6,909 ft), indicated by a road sign) being located in the latter canton, about 2 km south of the border with Uri. The valleys connected by the pass are that of the river Reuss, named the Urseren, and that of the river Ticino, named Valle Leventina. The Gotthard axis is the most important route between Central Switzerland as well as most of the northern part of the country and the southern region of Ticino. It is the most direct link between Zürich and Lugano and also between some regions of northern Europe and Italy (Rotterdam-Basel-Genoa axis).

The nearest towns are Hospental (7 km north) near Andermatt and Airolo (4 km south), respectively in the valleys of Urseren and Leventina. The region of Andermatt lies at the foot of the Furka and Oberalp Passes connecting the Rhone and Rhine Valleys thus making the Gotthard area a strategic place for transports and military (the Swiss Réduit for instance).

Just southeast of the culminating point of the Gotthard Pass, at an elevation of about 2,090 metres above sea level, are several lakes. The largest is named Lago della Piazza and has a surface of 3.94 hectares. South of Lago della Piazza are the Hospice (Italian: Ospizio) and National Museum, as well as a hotel and restaurants. Another official road sign displaying an elevation of 2,091 metres (6,860 ft) lies there.

A few kilometres away and slightly above the Gotthard Pass are found two large dams and artificial lakes: Lago di Lucendro at the foot of Pizzo Lucendro and Lago della Sella at the foot of Pizzo Centrale. They are respectively part of the Reuss and Ticino basin, although both are located within the canton of Ticino.

History

Though the pass was locally known in antiquity, it was not generally used until the early 13th century because travel involved fording the turbulent Reuss, swollen with snowmelt during the early summer, in the narrow steep-sided Schöllenen Gorge, below Andermatt.

The first wooden bridge across Schöllenen Gorge was built around 1220, and in the following years the pass rapidly gained in importance.

The bridge permitted traffic to follow the Reuss to its headwaters and over the saddle at the top—a continental divide between the Rhine, which flows into the North Sea, and the river Ticino towards Milan, which after leaving Switzerland flows into the Po and ultimately into the Adriatic Sea.

The Gotthard Pass was formerly known as Monte Tremolo (its southern slope is still known as Val Tremola).

A chapel dedicated to Saint Gotthard of Hildesheim (died in 1038, canonized 1131), who was considered the patron saint of mountain passes, was built on the southern slope of the pass and consecrated by the archbishop of Milan, Enrico da Settala, in 1230.[4] The pass soon became known after the saint, by as early as 1236.

The opening of the Schöllenen Gorge for traffic was an important factor in the original Swiss Confederacy. The three regions of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden (the Waldstätten or "forest communities") gained imperial immediacy under the Hohenstaufen emperors still in the first half of the 13th century. An important aspect of the early confederacy, expressed in the Pfaffenbrief of 1370, was the guarantee of peace along the road from Zürich to the Gotthard Pass.

The Swiss also had an interest in extending their influence south of the Alps to secure the trade route across the pass to Milan. Beginning in 1331, they initially exerted their influence through peaceful trade agreements, but in the 15th century, their involvement turned military. 1403 the upper Leventina, as the valley south of the pass is called, became a protectorate of Uri. Throughout the 15th century, a changeful struggle between the Swiss and the Duchy of Milan ensued, resulting ultimately in the Swiss conquest of the territory of the Ticino.

The "Devil's Bridge" (Teufelsbrücke) legend associated with the crossing of the Schöllenen Gorge is not medieval; it may date to the 16th century (attestation of the name Teiffels Brucken in 1587) but more likely formed in the 17th century, and is first recorded in the early 18th century, by Johann Jakob Scheuchzer.[5]

A new road, including a tunnel with a length of c. 60 m, was built in 1707/8. The tunnel, known as Urnerloch, was the first road tunnel to be built in the Alps. It was constructed by Pietro Morettini (1660–1737).

The path across Schöllenen Gorge, and thus across the pass, still carried only foot traffic and pack animals until 1775, when the first carriage made the journey on an improved road.

The new Gotthard road was built in 1830, wide enough to allow (single-lane) motorized traffic. It is said that the first car traversed the pass in 1895. The first reported surmounting of the pass in 1901 still took more than a day.

With the Gotthard Road Tunnel (opened in 1980) the pass itself was again reduced to limited importance for traffic.

The modern concrete span of the third Devil's Bridge (Teufelsbrücke, built 1958) showing an older bridge (built 1830) below

The modern concrete span of the third Devil's Bridge (Teufelsbrücke, built 1958) showing an older bridge (built 1830) below Gotthard Post near the summit

Gotthard Post near the summit Old road: summit of the Gotthard

Old road: summit of the Gotthard Gotthard Hospice

Gotthard Hospice

Tremola valley

Tremola valley

Roads, railways, and tunnels

In addition to the National Road 2, crossing the pass and connecting Göschenen with Airolo, several tunnels provide access through the massif. The first one, the 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) Gotthard Rail Tunnel, opened in 1882 for railway traffic at a cost of around 200 workers' lives (there is uncertainty as to the exact toll).[6] The second one, the 17 kilometres (11 mi) Gotthard Road Tunnel (a motorway tunnel), opened in 1980. It was closed for two months in 2001 following a fatal fire. Both railway and motorway tunnels have portals in Göschenen and Airolo, at around 1,150 metres above sea level, and are close to each other. Either rail and road traffics through these tunnels are sometimes shut down during harsh weather conditions, particularly in winter.

The last tunnel, the 57 kilometres (35 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel (a double-tube railway tunnel), opened in 2016. At around 500 metres above sea level, it provides for the first time a flat route through the massif and the Alps from the northern plains at Erstfeld to the southern plains at Bodio. It is the longest and deepest railway tunnel in the world. This tunnel, combined with two shorter tunnels planned near Zürich and Lugano as part of the NRLA project, reduced the 3 hour 40 min rail journey from Zürich to Milan by one hour, while increasing the size and number of trains that can operate along the route because the line is nearly level, compared with the spirals of the older tunnel.

| Route | Type | Major tunnel | Since | Maximum height | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pass | Bridle path | - | 13th century | 2,106 m | |

| Pass (Tremola) | Paved road | - | 1830 | 2,106 m | |

| Gotthard Railway (summit line) | Railway | Gotthard Tunnel | 1882 | 1,151 m | Second highest conventional railway in Switzerland, car shuttle train services from 1924 until 1980, world's longest tunnel until 1906[7] |

| Pass (National Road 2) | Highway | - | 1977 | 2,106 m | Closed to motorized traffic in winter from 1980 onwards |

| A2 | Motorway | Gotthard Road Tunnel | 1980 | 1,175 m | Second highest motorway in Switzerland,[8] lowest direct north-south road through the Alps, world's longest road tunnel until 2000[9] |

| Gotthard Railway (base line) | High-speed railway | Gotthard Base Tunnel | 2016 | 549 m | First flat route through the Alps, world's longest and deepest railway tunnel |

Illustrations

A number of international artists have been inspired by the dramatic scenery of the Gotthard Pass, the Schöllenen Gorge and the Teufelsbrücke.

.jpg.webp) The Gotthard Post (oil on canvas by Rudolf Koller, 1874)

The Gotthard Post (oil on canvas by Rudolf Koller, 1874) Winterreise 1790 über den Gotthard (colored engraving by Wilhelm Rothe according drawing by Johann Gottfried Jentzsch, 1790)

Winterreise 1790 über den Gotthard (colored engraving by Wilhelm Rothe according drawing by Johann Gottfried Jentzsch, 1790).jpg.webp) Construction of the Devil's Bridge (oil on canvas by Carl Blechen, c. 1833)

Construction of the Devil's Bridge (oil on canvas by Carl Blechen, c. 1833) The Teufelsbrücke, St. Gotthard (oil on canvas by J. M. W. Turner c. 1803/04)

The Teufelsbrücke, St. Gotthard (oil on canvas by J. M. W. Turner c. 1803/04) Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov Crossing St. Gotthard Pass in 1799 (by Alexander von Kotzebue)

Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov Crossing St. Gotthard Pass in 1799 (by Alexander von Kotzebue)

In popular culture

See also

Bibliography

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2020). Napoleon Absent, Coalition Ascendant: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 1. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3025-7.

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2021). The Coalition Crumbles, Napoleon Returns: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 2. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3034-9.

- Nicola Pfund, Sui passi in bicicletta - Swiss Alpine passes by bicycle, Fontana Edizioni, 2012, p. 78-87. ISBN 978-88-8191-281-0.

References

- Anna Roos (2017). Swiss Sensibility: The Culture of Architecture in Switzerland. Birkhäuser. p. 6. ISBN 9783035609226.

For thousands of years the Gotthard Pass has been an important threshold between north and south Europe and for many centuries has played a significant role in the economy and culture of central Switzerland. Since the early thirteenth century, the pass has been a vital trade route connecting different cultures and language regions.

- "Gotthard Pass Route: Airolo–San Gottardo–Andermatt". postauto.ch. PostBus Switzerland. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

The Gotthard, also known as the "King of Mountain Passes", is reached via the extraordinary mountain road with views of the old Tremola route.

- Radaelli, Giulia; Thurn, Nike (2019). Gegenwartsliteratur - Weltliteratur: Historische und theoretische Perspektiven. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. p. 251. ISBN 9783839433652.

...zwischen 1218 und 1231 ansetzen könne, und just in jenen Interdezennien sei ja die Schöllenen bezwungen worden, die Teufelsbrücke gebaut und der König der Pässe, das royale Zentralalpenmassiv, dem Transitverkehr erschlossen worden...

[...could start between 1218 and 1231, and it was precisely in those interdecades that the Schöllenen was conquered, the Teufelsbrücke was built and the king of passes, the royal massif in the central Alps, was opened up to transit traffic...] - Bruno Meier, Von Morgarten bis Marignano (2015), p. 23.

- Lauf-Belart, Gotthardpass (1924), 165f.

- Hans-Peter Bärtschi: Gotthardbahn in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2004-07-29.

- Until the opening of the Simplon Tunnel

- After the San Bernardino Tunnel

- Until the opening of the Lærdal Tunnel

- Rebecca Silverman (September 7, 2013). "Wolfsmund GN 1". Anime News Network. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

External links

- Cycling Elevation profiles for both sides on the old road

- Free Pictures St. Gotthard Pass

- The Gotthard, Switzerland

- Sankt Gotthard Pass Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). pp. 6–7.