Antiprism

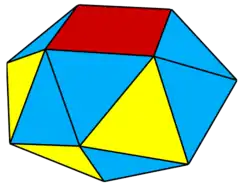

In geometry, an n-gonal antiprism or n-antiprism is a polyhedron composed of two parallel direct copies (not mirror images) of an n-sided polygon, connected by an alternating band of 2n triangles. They are represented by the Conway notation An.

| Set of uniform n-gonal antiprisms | |

|---|---|

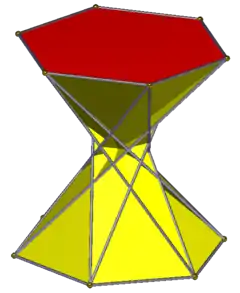

Uniform hexagonal antiprism (n = 6) | |

| Type | uniform in the sense of semiregular polyhedron |

| Faces | 2 regular n-gons 2n equilateral triangles |

| Edges | 4n |

| Vertices | 2n |

| Vertex configuration | 3.3.3.n |

| Schläfli symbol | { }⊗{n} [1] s{2,2n} sr{2,n} |

| Conway notation | An |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Dnd, [2+,2n], (2*n), order 4n |

| Rotation group | Dn, [2,n]+, (22n), order 2n |

| Dual polyhedron | convex dual-uniform n-gonal trapezohedron |

| Properties | convex, vertex-transitive, regular polygon faces, congruent & coaxial bases |

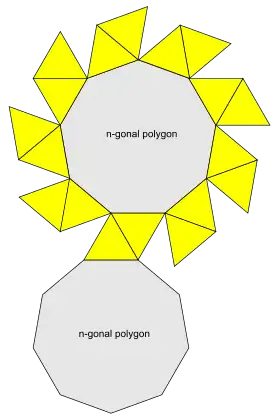

| Net | |

| |

| Net of uniform enneagonal antiprism (n = 9) | |

Antiprisms are a subclass of prismatoids, and are a (degenerate) type of snub polyhedron.

Antiprisms are similar to prisms, except that the bases are twisted relatively to each other, and that the side faces (connecting the bases) are 2n triangles, rather than n quadrilaterals.

The dual polyhedron of an n-gonal antiprism is an n-gonal trapezohedron.

History

At the intersection of modern-day graph theory and coding theory, the triangulation of a set of points have interested mathematicians since Isaac Newton, who fruitlessly sought a mathematical proof of the kissing number problem in 1694.[2] The existence of antiprisms was discussed, and their name was coined by Johannes Kepler, though it is possible that they were previously known to Archimedes, as they satisfy the same conditions on faces and on vertices as the Archimedean solids. According to Ericson and Zinoviev, Harold Scott MacDonald Coxeter wrote at length on the topic,[2] and was among the first to apply the mathematics of Victor Schlegel to this field.

Knowledge in this field is "quite incomplete" and "was obtained fairly recently", i.e. in the 20th century. For example, as of 2001 it had been proven for only a limited number of non-trivial cases that the n-gonal antiprism is the mathematically optimal arrangement of 2n points in the sense of maximizing the minimum Euclidean distance between any two points on the set: in 1943 by László Fejes Tóth for 4 and 6 points (digonal and trigonal antiprisms, which are Platonic solids); in 1951 by Kurt Schütte and Bartel Leendert van der Waerden for 8 points (tetragonal antiprism, which is not a cube).[2]

The chemical structure of binary compounds has been remarked to be in the family of antiprisms;[3] especially those of the family of boron hydrides (in 1975) and carboranes because they are isoelectronic. This is a mathematically real conclusion reached by studies of X-ray diffraction patterns,[4] and stems from the 1971 work of Kenneth Wade,[5] the nominative source for Wade's rules of polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory.

Rare-earth metals such as the lanthanides form antiprismatic compounds with some of the halides or some of the iodides. The study of crystallography is useful here.[6] Some lanthanides, when arranged in peculiar antiprismatic structures with chlorine and water, can form molecule-based magnets.[7]

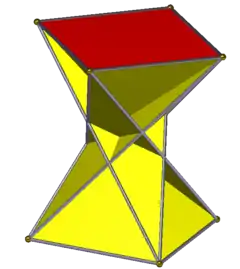

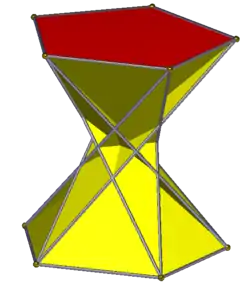

Right antiprism

For an antiprism with regular n-gon bases, one usually considers the case where these two copies are twisted by an angle of 180/n degrees.

The axis of a regular polygon is the line perpendicular to the polygon plane and lying in the polygon centre.

For an antiprism with congruent regular n-gon bases, twisted by an angle of 180/n degrees, more regularity is obtained if the bases have the same axis: are coaxial; i.e. (for non-coplanar bases): if the line connecting the base centers is perpendicular to the base planes. Then the antiprism is called a right antiprism, and its 2n side faces are isosceles triangles.

Uniform antiprism

A uniform n-antiprism has two congruent regular n-gons as base faces, and 2n equilateral triangles as side faces.

Uniform antiprisms form an infinite class of vertex-transitive polyhedra, as do uniform prisms. For n = 2, we have the regular tetrahedron as a digonal antiprism (degenerate antiprism); for n = 3, the regular octahedron as a triangular antiprism (non-degenerate antiprism).

| Antiprism name | Digonal antiprism | (Trigonal) Triangular antiprism |

(Tetragonal) Square antiprism |

Pentagonal antiprism | Hexagonal antiprism | Heptagonal antiprism | Octagonal antiprism | Enneagonal antiprism | Decagonal antiprism | Hendecagonal antiprism | Dodecagonal antiprism | ... | Apeirogonal antiprism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhedron image | ... | ||||||||||||

| Spherical tiling image | Plane tiling image | ||||||||||||

| Vertex config. | 2.3.3.3 | 3.3.3.3 | 4.3.3.3 | 5.3.3.3 | 6.3.3.3 | 7.3.3.3 | 8.3.3.3 | 9.3.3.3 | 10.3.3.3 | 11.3.3.3 | 12.3.3.3 | ... | ∞.3.3.3 |

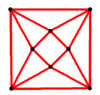

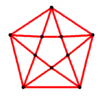

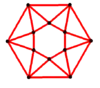

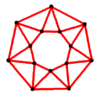

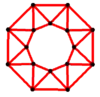

Schlegel diagrams

A3 |

A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

A7 |

A8 |

Cartesian coordinates

Cartesian coordinates for the vertices of a right n-antiprism (i.e. with regular n-gon bases and 2n isosceles triangle side faces) are:

where 0 ≤ k ≤ 2n – 1;

if the n-antiprism is uniform (i.e. if the triangles are equilateral), then:

Volume and surface area

Let a be the edge-length of a uniform n-gonal antiprism; then the volume is:

and the surface area is:

Furthermore, the volume of a right n-gonal antiprism with side length of its bases l and height h is given by:

Note that the volume of a right n-gonal prism with the same l and h is:

which is smaller than that of an antiprism.

Related polyhedra

There are an infinite set of truncated antiprisms, including a lower-symmetry form of the truncated octahedron (truncated triangular antiprism). These can be alternated to create snub antiprisms, two of which are Johnson solids, and the snub triangular antiprism is a lower symmetry form of the regular icosahedron.

| Antiprisms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

... |

| s{2,4} | s{2,6} | s{2,8} | s{2,10} | s{2,2n} |

| Truncated antiprisms | ||||

|

|

|

|

... |

| ts{2,4} | ts{2,6} | ts{2,8} | ts{2,10} | ts{2,2n} |

| Snub antiprisms | ||||

| J84 | Icosahedron | J85 | Irregular faces... | |

|

|

|

|

... |

| ss{2,4} | ss{2,6} | ss{2,8} | ss{2,10} | ss{2,2n} |

Four-dimensional antiprisms can be defined as having two dual polyhedra as parallel opposite faces, so that each three-dimensional face between them comes from two dual parts of the polyhedra: a vertex and a dual polygon, or two dual edges. Every three-dimensional polyhedron is combinatorially equivalent to one of the two opposite faces of a four-dimensional antiprism, constructed from its canonical polyhedron and its polar dual.[8] However, there exist four-dimensional polyhedra that cannot be combined with their duals to form five-dimensional antiprisms.[9]

Symmetry

The symmetry group of a right n-antiprism (i.e. with regular bases and isosceles side faces) is Dnd = Dnv of order 4n, except in the cases of:

- n = 2: the regular tetrahedron, which has the larger symmetry group Td of order 24 = 3×(4×2), which has three versions of D2d as subgroups;

- n = 3: the regular octahedron, which has the larger symmetry group Oh of order 48 = 4×(4×3), which has four versions of D3d as subgroups.

The symmetry group contains inversion if and only if n is odd.

The rotation group is Dn of order 2n, except in the cases of:

- n = 2: the regular tetrahedron, which has the larger rotation group T of order 12 = 3×(2×2), which has three versions of D2 as subgroups;

- n = 3: the regular octahedron, which has the larger rotation group O of order 24 = 4×(2×3), which has four versions of D3 as subgroups.

Note: The right n-antiprisms have congruent regular n-gon bases and congruent isosceles triangle side faces, thus have the same (dihedral) symmetry group as the uniform n-antiprism, for n ≥ 4.

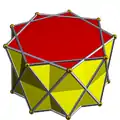

Star antiprism

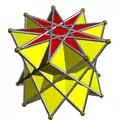

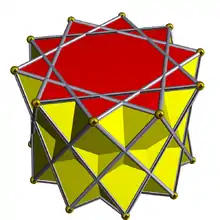

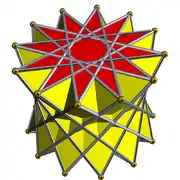

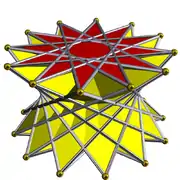

5/2-antiprism |

5/3-antiprism | ||||

9/2-antiprism |

9/4-antiprism |

9/5-antiprism | |||

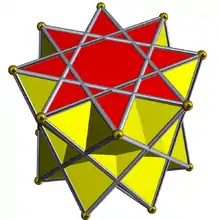

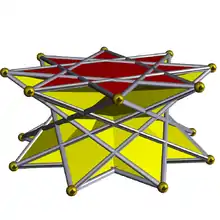

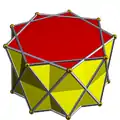

Uniform star antiprisms are named by their star polygon bases, {p/q}, and exist in prograde and in retrograde (crossed) solutions. Crossed forms have intersecting vertex figures, and are denoted by "inverted" fractions: p/(p – q) instead of p/q; example: 5/3 instead of 5/2.

A right star antiprism has two congruent coaxial regular convex or star polygon base faces, and 2n isosceles triangle side faces.

Any star antiprism with regular convex or star polygon bases can be made a right star antiprism (by translating and/or twisting one of its bases, if necessary).

In the retrograde forms but not in the prograde forms, the triangles joining the convex or star bases intersect the axis of rotational symmetry. Thus:

- Retrograde star antiprisms with regular convex polygon bases cannot have all equal edge lengths, so cannot be uniform. "Exception": a retrograde star antiprism with equilateral triangle bases (vertex configuration: 3.3/2.3.3) can be uniform; but then, it has the appearance of an equilateral triangle: it is a degenerate star polyhedron.

- Similarly, some retrograde star antiprisms with regular star polygon bases cannot have all equal edge lengths, so cannot be uniform. Example: a retrograde star antiprism with regular star 7/5-gon bases (vertex configuration: 3.3.3.7/5) cannot be uniform.

Also, star antiprism compounds with regular star p/q-gon bases can be constructed if p and q have common factors. Example: a star 10/4-antiprism is the compound of two star 5/2-antiprisms.

| Symmetry group | Uniform stars | Right stars | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D4d [2+,8] (2*4) |

3.3/2.3.4 | ||||

| D5h [2,5] (*225) |

3.3.3.5/2 |

3.3/2.3.5 | |||

| D5d [2+,10] (2*5) |

3.3.3.5/3 | ||||

| D6d [2+,12] (2*6) |

3.3/2.3.6 | ||||

| D7h [2,7] (*227) |

3.3.3.7/2 |

3.3.3.7/4 | |||

| D7d [2+,14] (2*7) |

3.3.3.7/3 | ||||

| D8d [2+,16] (2*8) |

3.3.3.8/3 |

3.3.3.8/5 | |||

| D9h [2,9] (*229) |

3.3.3.9/2 |

3.3.3.9/4 | |||

| D9d [2+,18] (2*9) |

3.3.3.9/5 | ||||

| D10d [2+,20] (2*10) |

3.3.3.10/3 | ||||

| D11h [2,11] (*2.2.11) |

3.3.3.11/2 |

3.3.3.11/4 |

3.3.3.11/6 | ||

| D11d [2+,22] (2*11) |

3.3.3.11/3 |

3.3.3.11/5 |

3.3.3.11/7 | ||

| D12d [2+,24] (2*12) |

3.3.3.12/5 |

3.3.3.12/7 | |||

| ... | ... | ||||

See also

- Apeirogonal antiprism

- Grand antiprism – a four-dimensional polytope

- One World Trade Center, a building consisting primarily of an elongated square antiprism

- Skew polygon

References

- N.W. Johnson: Geometries and Transformations, (2018) ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5 Chapter 11: Finite symmetry groups, 11.3 Pyramids, Prisms, and Antiprisms, Figure 11.3c

- Ericson, Thomas; Zinoviev, Victor (2001). "Codes in dimension n = 3". Codes on Euclidean Spheres. North-Holland Mathematical Library. Vol. 63. pp. 67–106. doi:10.1016/S0924-6509(01)80048-9. ISBN 9780444503299.

- Beall, Herbert; Gaines, Donald F. (2003). "Boron Hydrides". Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology. pp. 301–316. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227410-5/00073-9. ISBN 9780122274107.

- “Boron Hydride Chemistry” (E. L. Muetterties, ed.), Academic Press, New York

- Wade, K. (1971). "The structural significance of the number of skeletal bonding electron-pairs in carboranes, the higher boranes and borane anions, and various transition-metal carbonyl cluster compounds". J. Chem. Soc. D. 1971 (15): 792–793. doi:10.1039/C29710000792.

- Meyer, Gerd (2014). "Symbiosis of Intermetallic and Salt". Including Actinides. Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Vol. 45. pp. 111–178. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63256-2.00264-3. ISBN 9780444632562.

- Bartolomé, Elena; Arauzo, Ana; Luzón, Javier; Bartolomé, Juan; Bartolomé, Fernando (2017). Magnetic Relaxation of Lanthanide-Based Molecular Magnets. Handbook of Magnetic Materials. Vol. 26. pp. 1–289. doi:10.1016/bs.hmm.2017.09.002. ISBN 9780444639271.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2005). "Are prisms and antiprisms really boring? (Part 3)" (PDF). Geombinatorics. 15 (2): 69–78. MR 2298896.

- Dobbins, Michael Gene (2017). "Antiprismlessness, or: reducing combinatorial equivalence to projective equivalence in realizability problems for polytopes". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 57 (4): 966–984. doi:10.1007/s00454-017-9874-y. MR 3639611.

- Anthony Pugh (1976). Polyhedra: A visual approach. California: University of California Press Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-03056-7. Chapter 2: Archimedean polyhedra, prisms and antiprisms

Media related to Antiprisms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antiprisms at Wikimedia Commons- Weisstein, Eric W. "Antiprism". MathWorld.

- Nonconvex Prisms and Antiprisms

- Paper models of prisms and antiprisms