Strabismus surgery

Strabismus surgery (also: extraocular muscle surgery, eye muscle surgery, or eye alignment surgery) is surgery on the extraocular muscles to correct strabismus, the misalignment of the eyes.[1] Strabismus surgery is a one-day procedure that is usually performed under general anesthesia most commonly by either a neuro- or pediatric ophthalmologist.[1] The patient spends only a few hours in the hospital with minimal preoperative preparation. After surgery, the patient should expect soreness and redness but is generally free to return home.[1]

| Strabismus surgery | |

|---|---|

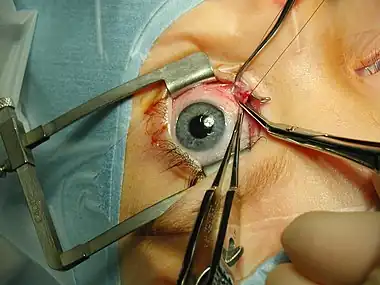

Isolating the inferior rectus muscle | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

History

The earliest successful strabismus surgery intervention is known to have been performed on 26 October 1839 by Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach on a 7-year-old esotropic child; a few earlier attempts had been performed in 1818 by William Gibson of Baltimore, a general surgeon and professor at the University of Maryland.[2] The idea of treating strabismus by cutting some of the extraocular muscle fibers was published in American newspapers by New York oculist John Scudder in 1837.[3]

Indications

Strabismus surgery is one of many options used to treat any misalignment of the eyes, called strabismus. This misalignment or "crossing" of the eyes can be caused by a variety of issues. Surgery is indicated when other, less invasive methods have been unable to treat the misalignment or when the procedure will significantly improve quality of life and/or visual function.[4] The type of surgery for a given patient depends on the type of strabismus they are experiencing. Exodeviations are when the misalignment of the eyes is divergent ("crossing out") and esodeviations are when the misalignment is convergent ("crossing in").[4] These conditions are further categorized based on when the misalignment is present. If it is latent the condition is called a "-phoria" and if it is present all the time it is a "-tropia".[4] Esotropias measuring more than 15 prism diopters (PD) and exotropias more than 20 PD that have not responded to refractive correction can be considered candidates for surgery.[5]

Techniques

The goal of strabismus surgery is to correct misalignment of the eyes. This is achieved by loosening or tightening the extraocular muscles in order to weaken or strengthen them, respectively.[1] There are two main types of extraocular muscles - rectus muscles and oblique muscles - which have specific procedures to achieve the desired results.[4] The amount of weakening or strengthening required is determined through in-office measurements of the eye misalignment. Measured in PD, the size of the deviation is used along with established formulas and tables to inform the surgeon how the muscle must be manipulated in surgery.[4]

Rectus muscle procedures

The main procedure used to weaken a rectus muscle is called a recession.[4] This involves detaching the muscle from its original insertion on the eye and moving it towards the back of the eye a specific amount.[1] If after a recession the muscle requires more weakening a marginal myotomy can be performed, where a cut is made part way across the muscle.[4] The procedures used to strengthen rectus muscles include resections and plications. A resection is when a portion of the muscle is cut away and the new shortened muscle is reattached to the same insertion point. A plication on the other hand is when the muscle is folded and secured to the outer white portion of the eye, known as the sclera.[4] Plication has the advantages of being a quicker procedure that involves less trauma than a resection and preserves the anterior ciliary arteries - the latter of which minimizes the risk of blood loss to the front of the eye allowing for operation on multiple muscles at one time.[6] Studies on horizontal rectus muscle surgeries have shown that both procedures have similar success rates and no difference in post-operative exodrift or overcorrection rate was discovered.[6] However, further investigation is required to determine if there is any difference in long term effects from the two procedures.[6]

Because of the antagonistic pairings of the rectus muscles and the fact that strabismus can be a binocular problem, in certain cases surgeons have the option of operating on either one eye or both eyes. For example, a recent study compared the outcomes of bilateral lateral rectus recession and unilateral recession/resection of the later/medial recti for intermittent exotropia.[7] This study showed that the unilateral procedure had higher success rates and lower recurrence rates for this specific condition.[7] This is not necessarily true for all types of strabismus and further investigation is required to reach a consensus on this particular aspect of the surgery.

Oblique muscle procedures

There are two oblique muscles attached to the eye - the superior oblique and the inferior oblique - which each have their respective procedures.[4]

Inferior oblique

The inferior oblique is weakened through a recession and anteriorization where the muscle is detached from the eye and reinserted at a spot anterior to the original insertion.[4] Some surgeons will alternatively perform a myotomy or myectomy, where a muscle is either cut or has a portion of it removed, respectively.[4] The inferior oblique muscle is rarely tightened due to the technical difficulty of the procedure and the possibility of damage to the macula, which is responsible for central vision.[4]

Superior oblique

The superior oblique is weakened through either a tenotomy or tenectomy, where part of the muscle tendon is either cut across or removed, respectively.[4] The superior oblique is strengthened by folding and securing the tendon to reduce its length, which is called a tuck.[4]

Adjustable sutures

A technique that is more commonly used for more complicated cases of strabismus is that of adjustable suture surgery. This technique allows for the adjustment of sutures after the initial procedure in order to theoretically achieve a better and more individualized result. This often requires dedicated and specific training in this uncommon procedure that has been reported to be performed in only 7.42% of all strabismus cases.[8] Studies have not shown any significant advantage to performing this type of surgery on most forms of simple strabismus. However, its use in some complex cases such as reoperations, strabismus with large or unstable angle, or strabismus in high myopia has been indicated.[8] The specific circumstances in which this technique is considered to be superior to non-adjustable suture surgery require further investigation.

Minimally invasive strabismus surgery

A relatively new method, primarily devised by Swiss ophthalmologist Daniel Mojon, is minimally invasive strabismus surgery (MISS)[9] which has the potential to reduce the risk of complications and lead to faster visual rehabilitation and wound healing. Done under the operating microscope, the incisions into the conjunctiva are much smaller than in conventional strabismus surgery. A study published in 2017 documented fewer conjunctival and eyelid swelling complications in the immediate postoperative period after MISS with long-term results being similar between both groups.[10] MISS can be used to perform all types of strabismus surgery, namely rectus muscle recessions, resections, transpositions, and plications even in the presence of limited motility.[11]

Outcomes

A strabismus surgery is considered a success when the overall deviation has been corrected 60% or more or if the deviation is under 10 PD 6 weeks after the surgery.[5]

Unsatisfactory alignment

Surgical intervention can result in the eyes being entirely aligned (orthophoria) or nearly so, or it can result in an alignment that is not the desired result. There are many possible types of misalignment that can occur after the surgery including undercorrection, overcorrection, and torsional misalignment.[12] Treating a case of unsatisfactory alignment often involves prisms, botulinum toxin injections, or more surgery. The likelihood that the eyes will stay misaligned over the longer term is higher if the patient is able to achieve some degree of binocular fusion after surgery than if not.[4] There is tentative evidence that children with infantile esotropia achieve better binocular vision post-operatively if the surgical treatment is performed early (see: Infantile esotropia#Surgery). A recent study reported the reoperation rate in a sample of over 6000 patients being 8.5%.[13]

Psychosocial outcomes

Strabismus has been shown to have a variety of negative psychosocial effects on affected patients. Patients are often more fearful, anxious, have lower self-esteem, and increased interpersonal-sensitivity.[14] These negative impacts often start in childhood and then progress throughout childhood and adolescence if the misalignment is not corrected quickly.[14] Unfortunately there is also data to suggest that society sees this condition as one that negatively affects many qualities important to self-sufficient function such as responsibility, leadership ability, communication, and even intelligence. However, much of this critical mental health burden has been shown to be relieved by corrective surgery.[14] Significant increases in self confidence and self-esteem as well as a reduction in general as well as social anxiety was observed. Overall, strabismus surgery has been shown to successfully improve upon many of the negative impacts strabismus can have on one's mental health.[14]

Complications

Complications that occur rarely or very rarely following surgery include: eye infection, hemorrhage in case of scleral perforation, muscle slip or detachment, or even loss of vision. Eye infection occurs at a rate between 1 in 1100 and 1 in 1900 and can lead to permanent loss of vision if not properly treated.[15] Surgeons take many measures to prevent infection such as careful surgical draping, using povidone iodine as both drops and a solution to soak the sutures in, as well as a post-op course of steroids and antibiotics.[15] There is generally minimal bleeding during strabismus surgery, but medications such as anti-platelet agents and anticoagulants can lead to vision threatening complications retrobulbar hemorrhage.[16]

Diplopia

Diplopia, or double vision, occurs commonly after strabismus surgery. Although the surgery can be used to treat some types of double vision, it can instead end up making existing symptoms worse or create a new type of double vision.[12] The type of double vision can be horizontal, vertical, torsional, or a combination. Treatment of the double vision depends on both the type of double vision and the ability of two eyes to work together, also called binocular function.[12] Diplopia with normal binocular function is treated with prism glasses, botulinum injections into the muscles, or repeated surgery.[12] If binocular function is not normal, a more individualized approach is necessary to best suit the patient's needs.[12]

Scarring

Eye muscle surgery gives rise to scarring (fibrosis) as a result of the trauma caused to the ocular tissues.[4] The goal of surgery is to produce a thin line of firm scar tissue where the muscle is reattached to the sclera. However, the process of surgery can also result in the formation of scar tissue on other parts of eye. These adhesions can, in rare cases, affect the motion of the eye and the desired alignment.[17] If scarring is extensive, it may be seen as raised and red tissue on the white of the eye.[4] Fibrosis reducing measures such as cryopreserved amniotic membrane and mitomycin C have been shown to have some utility during surgery.[17]

Oculocardiac reflex

Very rarely, potentially life-threatening complications may occur during strabismus surgery due to the oculocardiac reflex.[18] This is a physiologic reflex that is described as a reduction in heart rate due to pressure on the globe or traction on the extraocular muscles. It involves activation of the trigeminal nerve leading to activation of the vagus nerve due to the internuclear communication.[18] Although the most common arrhythmia is sinus bradycardia, asystole can be seen in its severe form.[4] The reflex can also have non cardiac effects such as postoperative nausea and vomiting, which is an extremely common consequence of strabismus surgery in children.[18]

See also

References

- "Strabismus Surgery - American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus". aapos.org. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Boger WP (1986-07-01). "Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management of Strabismus". Archives of Ophthalmology. 104 (7): 983. doi:10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190041032. ISSN 0003-9950.

- Leffler CT, Schwartz SG, Le JQ (January 2017). "American Insight Into Strabismus Surgery Before 1838". Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases. 9: 1179172117729367. doi:10.1177/1179172117729367. PMC 5598791. PMID 28932129.

- 2019-2020 basic and clinical science course, complete print set. American Academic of Ophthalmology. 2019. ISBN 978-1-68104-178-0. OCLC 1100599770.

- Kanukollu, Venkata M.; Sood, Gitanjli (2020), "Strabismus", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32809617, retrieved 2020-11-05

- Issaho DC, de Freitas D, Cronemberger MF (2020-07-03). "Plication versus Resection in Horizontal Strabismus Surgery: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis". Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020: 5625062. doi:10.1155/2020/5625062. PMC 7354662. PMID 32714609.

- Sun Y, Zhang T, Chen J (March 2018). "Bilateral lateral rectus recession versus unilateral recession resection for basic intermittent exotropia: a meta-analysis". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 256 (3): 451–458. doi:10.1007/s00417-018-3912-1. PMID 29368040. S2CID 3510110.

- Gawęcki M (January 2020). "Adjustable Versus Nonadjustable Sutures in Strabismus Surgery-Who Benefits the Most?". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (2): 292. doi:10.3390/jcm9020292. PMC 7073633. PMID 31973012.

- Mojon DS (February 2015). "Review: minimally invasive strabismus surgery". Eye. 29 (2): 225–33. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.281. PMC 4330290. PMID 25431106.

- Gupta P, Dadeya S, Bhambhawani V (July 2017). "Comparison of Minimally Invasive Strabismus Surgery (MISS) and Conventional Strabismus Surgery Using the Limbal Approach". Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 54 (4): 208–215. doi:10.3928/01913913-20170321-01. PMID 28820930.

- Asproudis I, Kozeis N, Katsanos A, Jain S, Tranos PG, Konstas AG (April 2017). "A Review of Minimally Invasive Strabismus Surgery (MISS): Is This the Way Forward?". Advances in Therapy. 34 (4): 826–833. doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0498-7. PMID 28251554.

- Sharma M, Hunter DG (2018-01-02). "Diplopia after Strabismus Surgery". Seminars in Ophthalmology. 33 (1): 102–107. doi:10.1080/08820538.2017.1353827. PMID 29193991. S2CID 3396436.

- Leffler CT, Vaziri K, Cavuoto KM, McKeown CA, Schwartz SG, Kishor KS, Pariyadath A (August 2015). "Strabismus Surgery Reoperation Rates With Adjustable and Conventional Sutures". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 160 (2): 385–390.e4. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.014. PMC 4506871. PMID 26002082.

- Al Shehri F, Duan L, Ratnapalan S (October 2020). "Psychosocial impacts of adult strabismus and strabismus surgery: a review of the literature". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 55 (5): 445–451. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.08.013. PMID 33131636. S2CID 79231341.

- Schnall, Bruce Michael; Feingold, Anat (September 2018). "Infection following strabismus surgery". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 29 (5): 407–411. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000507. ISSN 1040-8738. PMID 29994852. S2CID 51610574.

- Robbins, Shira L.; Wang, Jeffrey W.; Frazer, Jeffrey R.; Greenberg, Mark (August 2019). "Anticoagulation: a practical guide for strabismus surgeons". Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 23 (4): 193–199. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2018.12.008. ISSN 1091-8531. PMID 30981895. S2CID 115203690.

- Kassem RR, El-Mofty RM (May 2019). "Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in Strabismus Surgery". Current Eye Research. 44 (5): 451–464. doi:10.1080/02713683.2018.1562555. PMID 30575427. S2CID 58542483.

- Dunville LM, Sood G, Kramer J (2020). "Oculocardiac Reflex". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763007. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

Further reading

- Wright KW, Thompson LS, Strube YN, Coats DK (August 2014). "Novel strabismus surgical techniques—not the standard stuff". Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 18 (4): e47. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.07.152.

- Kushner BJ (May 2014). "The benefits, risks, and efficacy of strabismus surgery in adults". Optometry and Vision Science. 91 (5): e102-9. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000248. PMID 24739461. S2CID 3166398.

- Engel JM (September 2012). "Adjustable sutures: an update". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 23 (5): 373–6. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283567321. PMID 22871879. S2CID 5229293.

External links

- Strabismus Surgery, Horizontal on EyeWiki from the American Academy of Ophthalmology

- Strabismus Surgery Complications on EyeWiki from the American Academy of Ophthalmology