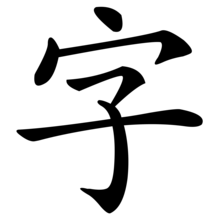

Courtesy name

A courtesy name (Chinese: 字; pinyin: zì; lit. 'character'), also known as a style name, is a name bestowed upon one at adulthood in addition to one's given name.[1] This practice is a tradition in the East Asian cultural sphere, including China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.[2]

| Courtesy name (Zi) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chinese name | |

| Traditional Chinese | (表) 字 |

| Hanyu Pinyin | (biǎo) zì |

| Wade–Giles | (piao)-tzu |

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | biểu tự tên tự tên chữ |

| Chữ Hán | 表字 |

| Chữ Nôm | 𠸜字 𠸜𡨸 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 자 |

| Hanja | 字 |

| Revised Romanization | ja |

| McCune–Reischauer | cha |

| Japanese name | |

| Kanji | 字 |

| Hiragana | あざな |

| Revised Hepburn | azana |

A courtesy name is not to be confused with an art name, another frequently mentioned term for an alternative name in East Asia, which is closer to the concept of a pen name or a pseudonym.[1]

Usage

A courtesy name is a name traditionally given to Chinese men at the age of 20 sui, marking their coming of age. It was sometimes given to women, usually upon marriage.[1] The practice is no longer common in modern Chinese society. According to the Book of Rites, after a man reached adulthood, it was disrespectful for others of the same generation to address him by his given name.[3] Thus, the given name was reserved for oneself and one's elders, whereas the courtesy name would be used by adults of the same generation to refer to one another on formal occasions or in writing. Another translation of zi is "style name", but this translation has been criticised as misleading, because it could imply an official or legal title.[1]

Generally speaking, courtesy names before the Qin dynasty were one syllable, and from the Qin to the 20th century they were mostly disyllabic, consisting of two Chinese characters.[1] Courtesy names were often based on the meaning of the person's given name. For example, Chiang Kai-shek's given name (中正, romanized as Chung-cheng) and courtesy name (介石, romanized as Kai-shek) are both from the yù hexagram of I Ching.

Another way to form a courtesy name is to use the homophonic character zi (子) – a respectful title for a man – as the first character of the disyllabic courtesy name. Thus, for example, Gongsun Qiao's courtesy name was Zichan (子產), and Du Fu's: Zimei (子美). It was also common to construct a courtesy name by using as the first character one which expresses the bearer's birth order among male siblings in his family. Thus Confucius, whose name was Kong Qiu (孔丘), was given the courtesy name Zhongni (仲尼), where the first character zhong indicates that he was the second son born into his family. The characters commonly used are bo (伯) for the first, zhong (仲) for the second, shu (叔) for the third, and ji (季) typically for the youngest, if the family consists of more than three sons. General Sun Jian's four sons, for instance, were Sun Ce (伯符, Bófú), Sun Quan (仲謀, Zhòngmóu), Sun Yi (叔弼, Shūbì) and Sun Kuang (季佐, Jìzuǒ).

Reflecting a general cultural tendency to regard names as significant, the choice of what name to bestow upon one's children was considered very important in traditional China.[4] Yan Zhitui of the Northern Qi dynasty asserted that whereas the purpose of a given name was to distinguish one person from another, a courtesy name should express the bearer's moral integrity.

Prior to the twentieth century, sinicized Koreans, Vietnamese, and Japanese were also referred to by their courtesy name. The practice was also adopted by some Mongols and Manchus after the Qing conquest of China.

Examples

| Chinese | Family name | Given name | Courtesy name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lǎozǐ 老子 | Lǐ 李 | Ěr 耳 | Bóyáng 伯陽 |

| Kǒngzǐ (Confucius) 孔子 | Kǒng 孔 | Qiū 丘 | Zhòngní 仲尼 |

| Sūnzǐ (Sun Tzu) 孫子 | Sūn 孫 | Wǔ 武 | Chángqīng 長卿 |

| Cáo Cāo 曹操 | Cáo 曹 | Cāo 操 | Mèngdé 孟德 |

| Guān Yǔ 關羽 | Guān 關 | Yǔ 羽 | Yúncháng 雲長 |

| Liú Bèi 劉備 | Liú 劉 | Bèi 備 | Xuándé 玄德 |

| Zhūgé Liàng 諸葛亮 | Zhūgé 諸葛 | Liàng 亮 | Kǒngmíng 孔明 |

| Zhào Yún 趙雲 | Zhào 趙 | Yún 雲 | Zǐlóng 子龍 |

| Lǐ Bái 李白 | Lǐ 李 | Bái 白 | Tàibái 太白 |

| Sū Dōngpō 蘇東坡 | Sū 蘇 | Shì 軾 | Zǐzhān 子瞻 |

| Yuè Fēi 岳飛 | Yuè 岳 | Fēi 飛 | Péngjǔ 鵬舉 |

| Yuán Chónghuàn 袁崇煥 | Yuán 袁 | Chónghuàn 崇煥 | Yuánsù 元素 |

| Liú Jī 劉基 | Liú 劉 | Jī 基 | Bówēn 伯溫 |

| Táng Yín 唐寅 | Táng 唐 | Yín 寅 | Bóhǔ 伯虎 |

| Máo Zédōng 毛澤東 | Máo 毛 | Zédōng 澤東 | Rùnzhī 潤之 |

| Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 | Jiǎng 蔣 | Zhōngzhèng 中正 | Jièshí 介石 |

| Hồ Chí Minh 胡志明 | Nguyễn 阮 | Sinh Cung 生恭 | Tất Thành 必誠 |

| I Sunsin 李舜臣 | I 李 | Sunsin 舜臣 | Yeohae 汝諧 |

See also

- Cognomen, the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome

References

- Wilkinson, Endymion Porter (2018). Chinese History: A New Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 143–145. ISBN 978-0998888309.

- Ulrich Theobald. Names of Persons and Titles of Rulers

- "Qū lǐ shàng" 曲禮上 [Summary of the Rules of Propriety Part 1]. Lǐjì 禮記 [Book of Rites]. Line 44.

A son at twenty is capped, and receives his appellation....When a daughter is promised in marriage, she assumes the hair-pin, and receives her appellation.

- Adamek, Piotr (2017). A Good Son is Sad If He Hears the Name of His Father: The Tabooing of Names in China as a Way of Implementing Social Values. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780367596712.