Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsids (Arabic: الحفصيون al-Ḥafṣiyūn) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descent[3] who ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, western Libya, and eastern Algeria) from 1229 to 1574.

Hafsid Kingdom Sultanate of Tunis | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1229–1574 | |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) | |||||||||||||||||

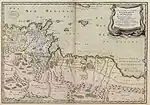

Realm of the Hafsid dynasty in 1400 (orange) | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tunis | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic, Berber | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (Sunni, Ibadi), Christianity (Roman Catholic), Judaism | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||

• 1229–1249 | Abu Zakariya | ||||||||||||||||

• 1574 | Muhammad VI | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1229 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1535 | |||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1574 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

History

Almohad Ifriqiya

The Hafsids were of Berber descent,[3] although to further legitimize their rule, they claimed Arab ancestry from the second Rashidun Caliph Omar.[4] The ancestor of the dynasty and from whom their name is derived was Abu Hafs Umar ibn Yahya al-Hintati, a Berber from the Hintata tribal confederation, which belonged to the greater Masmuda confederation of Morocco. He was a member of the council of ten and a close companion of Ibn Tumart. His original Berber name was "Faskat u-Mzal Inti", which later was changed to "Abu Hafs Umar ibn Yahya al-Hintati" (also known as "Umar Inti") since it was a tradition of Ibn Tumart to rename his close companions once they had adhered to his religious teachings. His son Abu Muhammad Abd al-Wahid ibn Abi Hafs, was appointed by the Almohad caliph Muhammad an-Nasir as governor of Ifriqiya, where he ruled from 1207 to 1221.[5][6][7]

Hafsid Kingdom and Caliphate

In 1229 Ifriqiyas governor, Abu Zakariya returned to Tunis after conquering Constantine and Béjaïa the same year and declared independence. After the split of the Hafsids from the Almohads under Abu Zakariya (1228–1249), Abu Zakariya organised the administration in Ifriqiya (the Roman province of Africa in modern Maghreb; today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria and western Libya) and built the city of Tunis up as the economic and cultural centre of the empire. At the same time, many Muslims from Al-Andalus fleeing the Christian Reconquista of Iberia were absorbed. He subsequently annexed Tripoli in 1234, Algiers in 1235, Chelif River 1236, and subdued important tribal confederations of the Berbers from 1235 to 1238.

He also conquered the Kingdom of Tlemcen in July 1242 forcing the Sultan of Tlemcen his vassals.

In December of that year, caliph Abd al-Wahid II, died, leaving Abu Zakariya as the most powerful ruler of Maghreb. At this time the Hafsids also occupied the Berber emirate of Siyilmasa which they retained for 30 years. By the end of his reign, the Marinid Dynasty of Morocco and several Muslim princes in Al-Andalus paid him tribute and acknowledged his nominal authority.

His successor Muhammad I al-Mustansir (1249–1277) proclaimed himself Caliph in 1256 and continued the policies of his father and extended the boundaries of his State by subjugating the central Maghreb, going so far as to impose his overlordship over the Kingdom of Tlemcen, northern Morocco and the Nasrids of Granada Spain. The Hafsids become completely independent in 1264. It was during his reign that the failed Eighth Crusade took place, led by St. Louis. After landing at Carthage, the King died of dysentery in the middle of his army decimated by disease in 1270.

Hafsid decline (14th century)

In the 14th century the empire underwent a temporary decline. Although the Hafsids succeeded for a time in subjugating the empire of the Abdalwadids of Tlemcen, between 1347 and 1357 they were twice conquered by the Marinids of Morocco. The Abdalwadids however could not defeat the Bedouin; ultimately, the Hafsids were able to regain their empire. During the same period plague epidemics brought to Ifriqiya from Sicily caused a considerable fall in population, further weakening the empire. To stop raids from southern tribes during plague epidemics, the Hafsids turned to the Banu Hilal to protect their rural population.[8]: 37

Peak (15th century)

During Abd al-Aziz's (1394–1434) reign the country experienced an era of prosperity as he proceeded to further consolidate the kingdom.

The beginning of his reign was not easy since the cities of the south revolted against him. However, the new sultan quickly regained their control: he reoccupied Tozeur (1404), Gafsa (1401), and Biskra (1402), and tribal power of the regions of Constantine and Bugia (1397–1402), and appointed governors of these regions to be elected, generally libertarian officers. He also intervened against his western and eastern neighbors by annexing Tripoli (1401), Algiers (1410–1411)[9] and by defeating the Zayyanid dynasty in 1424 and replacing it with a pro-Hafsid ruler[10] which would later revolt against him in 1428 and 1431.[11]

In 1429, the Hafsids attacked the island of Malta, and took 3000 slaves although they did not conquer the island.[12] Kaid Ridavan was the military leader during the attack.[13] The profits were used for a great building programme and to support art and culture. However, piracy also provoked retaliation from the Christians, which several times launched attacks and crusades against Hafsid coastal cities such as the Barbary crusade (1390), the Bona crusade (1399) and the capture of Djerba in 1423.

In 1432 Abd al-Aziz launched another expedition against Tlemcen and died during the campaign.

Under Uthman (1435–1488) the Hafsids reached their zenith, as the caravan trade through the Sahara and with Egypt was developed, as well as sea trade with Venice and Aragon. The Bedouins and the cities of the empire became largely independent, leaving the Hafsids in control of only Tunis and Constantine.

Uthman conquered Tripolitania in 1458 and appointed a governor in Ouargla in 1463.[14] He led two expeditions in Tlemcen in 1462 and 1466 and made the Zayyanids his vassals, the Wattasid state in Morocco also became a vassal of Uthman and therefore the entire Maghreb was briefly under the rule of the Hafsids.[15][16]

Fall of the Hafsids

In the 16th century the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire-supported Corsairs. The Ottomans conquered Tunis in 1534 and held it for one year, driving out the Hafsid ruler Muley Hassan. A year later the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V seized Tunis, drove the Ottomans out and restored Muley Hassan as a Habsburg tributary.[17] Due to the Ottoman threat, the Hafsids were vassals of Spain after 1535. The Ottomans again conquered Tunis in 1569 and held it for four years. Don Juan of Austria recaptured it in 1573. The Ottomans reconquered Tunis in 1574, and Muhammad VI, the last Caliph of the Hafsids, was brought to Constantinople and was subsequently executed due to his collaboration with Spain and the desire of the Ottoman Sultan to take the title of Caliph as he now controlled Mecca and Medina.

Economy

The Hafsids, with their location in Ifriqiya, was rich in agriculture and trade. Instead of placing the capital at inland cities such as Kairouan, Tunis was chosen as the capital due to its position on the coast as a port linking the Western and Eastern Mediterranean. Christian merchants from Europe were given their own enclaves in various cities on the Mediterranean coast, promoting trans-Mediterranean trade. Under the Hafsids, commerce and diplomatic relations with Christian Europe grew significantly,[18] however piracy against Christian shipping grew as well, particularly during the rule of Abd al-Aziz II (1394–1434). By the mid-14th century, the population of Tunis had grown to 100,000. The Hafsids also had a large stake in trans-Saharan trade through the caravan routes from Tunis to Timbuktu and from Tripoli to sub-Saharan Africa. The Tunisian population was also becoming more literate - Kairouan, Tunis and Bijaya had become homes to famous university mosques, with Kairouan becoming the center of the Maliki school of religious doctrine.[8]: 34–7

Science

Tunis became the capital of Ifriqiya under Almohad and Hafsid rule. This shift from Kairouan to Tunis improved the position of Al-Zaytuna Mosque and helped the Ez-Zitouna University to flourish and to become one of the major centres of Islamic learning. During that period, scientists contributed to advancing knowledge in different fields.

Ibn Khaldun was one of the most prominent philosopher on the Hafsid times. He received classical Islamic education in Ez-Zitouna University. With the help of the philosopher Al-Abili, Ibn Khaldun was introduced to mathematics, logic and philosophy.

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

The Hafsids were significant builders, particularly under the reigns of successful leaders like Abu Zakariya (r. 1229–1249) and Abu Faris (r. 1394–1434), though not many of their monuments have survived intact to the present-day.[19]: 208 While Kairouan remained an important religious center, Tunis was the capital and progressively replaced it as the main city of the region and the main center of architectural patronage. Unlike the architecture further west, Hafsid architecture was built primarily in stone (rather than brick or mudbrick) and appears to have featured much less decoration.[19]: 208 In reviewing the history of architecture in the western Islamic world, scholar Jonathan Bloom remarks that Hafsid architecture seems to have "largely charted a course independent of the developments elsewhere in the Maghrib [North Africa]".[19]: 213

The Kasbah Mosque of Tunis was one of the first works of this period, built by Abu Zakariya (the first independent Hafsid ruler) at the beginning of his reign. Its floor plan had noticeable differences from previous Almohad-period mosques but the minaret, completed in 1233, bears very strong resemblance the minaret of the earlier Almohad Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh.[19] Other foundations from the Hafsid period in Tunis include the Haliq Mosque (13th century) and the al-Hawa Mosque (1375). The Bardo Palace (today a national museum) was also begun by the Hafsids in the 15th century,[20] and is mentioned in historical records for the first time during the reign of Abu Faris.[19]: 208 The Hafsids also made significant renovations to the much older Great Mosque of Kairouan – renovating its ceiling, reinforcing its walls, and building or rebuilding two of its entrance gates in 1293 – as well as to the Great Mosque of al-Zaytuna in Tunis.[19]: 209

The Hafsids also introduced the first madrasas to the region, beginning with the Madrasa al-Shamma῾iyya built in Tunis in 1238[21][19]: 209 (or in 1249 according to some sources[22]: 296 [23]). This was followed by many others (almost all of them in Tunis) such as the Madrasa al-Hawa founded in the 1250s, the Madrasa al-Ma'ridiya (1282), and the Madrasa al-Unqiya (1341).[19] Many of these early madrasas, however, have been poorly preserved or have been considerably modified in the centuries since their foundation.[19][24] The Madrasa al-Muntasiriya, completed in 1437, is among the best preserved madrasas of the Hafsid period.[19]: 211

Flags

- Flags of Hafsids on portolans and from other sources

Early red flag with white or yellow crescent of the 14th century, reported by Marino Sanudo (ca. 1321), Angelino Dulcerta (1339) and the Catalan Atlas (1385)[25]

Early red flag with white or yellow crescent of the 14th century, reported by Marino Sanudo (ca. 1321), Angelino Dulcerta (1339) and the Catalan Atlas (1385)[25].svg.png.webp) Yellow with white crescent, the reconstructed flag of the 15th century

Yellow with white crescent, the reconstructed flag of the 15th century.svg.png.webp) White with blue crescent according to Jacobo Russo, 1550 (last period of the kingdom)

White with blue crescent according to Jacobo Russo, 1550 (last period of the kingdom)

Hafsid rulers

| History of Tunisia |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Algeria |

|---|

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. n. | Name | Birth date | Death date | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | Abu Muhammad Abd al-Wahid ibn Abi Hafs | unknown | 1222 | 1207–1222 | Not yet a sultan, just a local minor leader. |

| – | Abu Muhammad Abd Allah ibn Abd al-Wahid | unknown | 1229 | 1222–1229 | Not yet a sultan, just a local minor leader. |

| 1st | Abu Zakariya Yahya | 1203 | 5 October 1249 | 1229–1249 | |

| 2nd | Muhammad I al-Mustansir | 1228 | 1277 | 1249–1277 | |

| 3rd | Yahya II al-Wathiq | unknown | 1279 | 1277–1279 | |

| 4th | Ibrahim I | unknown | 1283 | 1279–1283 | |

| 5th | Abd al-Aziz I | unknown | 1283 | 1283 | |

| 6th | Ibn Abi Umara | unknown | 1284 | 1283–1284 | |

| 7th | Abu Hafs Umar bin Yahya | unknown | 1295 | 1284–1295 | |

| 8th | Abu Asida Muhammad II | 1279 | September 1309 | 1295–1309 | |

| 9th | Abu Yahya Abu Bakr ash-Shahid | unknown | September 1309 | 1309 | |

| 10th | Abu-l-Baqa Khalid An-Nasr | unknown | 1311 | 1309–1311 | |

| 11th | Abd al-Wahid Zakariya ibn al-Lihyani | 1253 | 1326 | 1311–1317 | |

| 12th | Abu Darba Muhammad Al-Mustansir | unknown | 1323 | 1317–1318 | |

| 13rd | Abu Yahya Abu Bakr II | unknown | 19 October 1346 | 1318–1346 | |

| 14th | Abu-l Abbas Ahmad | unknown | 1346 | 1346 | |

| 15th | Abu Hafs Umar II | unknown | 1347 | 1346–1347 | |

| 16th | Abu al-Abbas Ahmad al-Fadl al-Mutawakkil | unknown | 1350 | 1347–1350 | |

| 17th | Abu Ishaq Ibrahim II | October or November 1336 | 19 February 1369 | 1350–1369 | |

| 18th | Abu-l-Baqa Khalid II | unknown | November 1370 | 1369–1370 | |

| 19th | Ahmad II | 1329 | 3 June 1394 | 1370–1394 | |

| 20th | Abd al-Aziz II | 1361 | July 1434 | 1394–1434 | |

| 21st | Abu Abd-Allah Muhammad al-Muntasir | unknown | 16 September 1435 | 1434–1435 | |

| 22nd | Abu 'Amr 'Uthman | February 1419 | September 1488 | 1435–1488 | |

| 23rd | Abu Zakariya Yahya II | unknown | 1489 | 1488–1489 | |

| 24th | Abd al-Mu'min (Hafsid) | unknown | 1490 | 1489–1490 | |

| 25th | Yahya Zakariya | unknown | 1494 | 1490–1494 | |

| 26th | Abu Abdallah Muhammad IV al-Mutawakkil | unknown | 1526 | 1494–1526 | |

| 27th | Muhammad V (“Moulay Hasan”) | unknown | 1543 | 1526–1543 | |

| 28th | Ahmad III | c. 1500 | August 1575 | 1543–1569 | |

| Ottoman conquest (1569–1573) | |||||

| 29th | Muhammad VI | unknown | 1594 | 1573–1574 | |

References

- "الحفصيون/بنو حفص في تونس، بجاية وقسنطينة". www.hukam.net (in Arabic).

- "TunisiaArms". www.hubert-herald.nl.

- C. Magbaily Fyle, Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa, (University Press of America, 1999), 84.

- Fromherz, Allen James (2016). Near West: Medieval North Africa, Latin Europe and the Mediterranean in the Second Axial Age. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-1007-6.

- Fromherz, Allen J., "Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Hintātī", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson

- Idris, H. R. (1986) [1971]. "Ḥafṣids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, C.; Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. p. 66. ISBN 9004081186.

- Deverdun, G. (1986) [1971]. "Hintāta". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, C.; Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 9004081186.

- Roland Anthony Oliver; Roland Oliver; Anthony Atmore (2001). Medieval Africa, 1250–1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79372-8.

- نوري, عبد المجيد (March 2017). "العملة وتأثيراتها السياسية في تاريخ الغرب الإسلامي من مطلع القرن الخامس إلى أواخر القرن السابع الهجري 407 هـ - 674 هـ /1017 - 1275 م". Historical Kan Periodical (in Arabic). 10 (35): 172–175. doi:10.12816/0041490. ISSN 2090-0449.

- نوري, عبد المجيد (March 2017). "العملة وتأثيراتها السياسية في تاريخ الغرب الإسلامي من مطلع القرن الخامس إلى أواخر القرن السابع الهجري 407 هـ - 674 هـ / 1017 - 1275 م". Historical Kan Periodical (in Arabic). 10 (35): 172–175. doi:10.12816/0041490. ISSN 2090-0449.

- "Supplementum Epigraphicum GraecumSivrihissar (in vico). Op. cit. Op. cit. 334, n. 19". Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. doi:10.1163/1874-6772_seg_a2_597. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0313323291.

- Cauchi, Fr Mark (12 September 2004). "575th anniversary of the 1429 Siege of Malta". Times of Malta. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Braunschvig 1940, p. 260

- History of North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, from the Arab Conquest to 1830, Volume 2 Charles André Julien Routledge & K. Paul, 1970

- Jamil M. Abun-Nasr (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0

- Roger Crowley, Empires of the Sea, faber and faber 2008 p. 61

- Berry, LaVerle. "Hafsids". Libya: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Tunis". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2002). Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Hafsid". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Madrasa". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- "TunisiaArms".