Sumiyoshi Shrine (Shimonoseki)

Sumiyoshi Shrine (住吉神社) is a Shinto shrine in the Miyasumiyoshi neighborhood of the city of Shimonoseki in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. It is the ichinomiya of former Nagato Province. The main festival of the shrine is held annually on December 15.[1] Along with the more famous Sumiyoshi-taisha in Osaka and the Sumiyoshi Jinja in Fukuoka, it is one of the "Three Great Sumiyoshi" shrines; however whereas the Osaka Sumitomo-taisha enshrines the Nigi-Mitama, or placid spirit of the Sumiyoshi kami, the shrine in Shimonoseki enshrines the Ara-Mitama, or rough spirit of the kami.[2]

| Sumiyoshi Shrine 住吉神社 | |

|---|---|

_Honden.JPG.webp) Honden of Sumiyoshi Shrine

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Sumiyoshi sanjin |

| Festival | December 15 |

| Type | Sumiyoshi |

| Location | |

| Location | 11-1 Ichinomiyasumiyoshi 1-chōme, Shimonoseki-shi, Yamaguchi-ken 751-0805 |

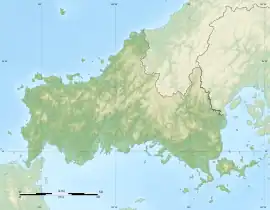

Sumiyoshi Shrine  Sumiyoshi Shrine (Shimonoseki) (Japan) | |

| Geographic coordinates | 33°59′58.6″N 130°57′23.6″E |

Enshrined kami

The kami enshrined at Sumiyoshi Jinja are:

- Sumiyoshi sanjin (住吉三神)

- Emperor Ōjin (応神天皇)

- Takenouchi no Sukune (武内宿禰命)

- Empress Jingū (神功皇后)

- Takeminakata (建御名方命)

History

The origins of Itakiso Jinja are unknown. Per the Nihon Shoki, when the legendary Empress Jingū embarked on her conquest of the Korean Peninsula, she entrusted the Sumitomo sanjin to protect her passage across the ocean. En route back to Japan, she had a message from the gods that their oracle was to be found in Nagato Province, where a shrine should be built. The shrine first appears in the historical record in an entry dated 859 in the Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku. In the 927 Engishiki it is listed as a Myojin Taisha (名神大社) and is called the ichinomiya of the province. The shrine was worshipped by the military classes and as a guardian of maritime traffic. From the Kamakura period, it received donations from successive shogun, including Minamoto no Yoritomo. Although the shrine declined in the Muromachi period, during the Sengoku and Edo Periods it was patronized by the Ōuchi clan and the Mōri clan, daimyō of Chōshū Domain.

After the Meiji Restoration, it was listed as a National Shrine, 2nd rank (国幣中社, Kokuhei Chūsha) in 1871, and promoted to a Imperial Shrine, 2nd rank (官幣中社, kanpei-chūsha) in 1911.[3]

The shrine is located a twenty-minute walk from Shin-Shimonoseki Station on the Sanyo Shinkansen.[4]

Cultural properties

National Treasures

- Honden, built in 1370. This a unique structure based on a modification of the nagare-zukuri style, but with five separate bays, each with its own small gable, to provide five sanctuaries, one for each of the five kami worshipped at the shrine. It interior is decorated with colored paintings.[5]

National Important Cultural Properties

- Haiden, constructed in 1539. It is a three by one bay structure with a single-gable roof which is covered in cypress bark shingles. This hall of worship is built at right angles to the center of the front of the main hall. The floor is low and open on all sides. Detailed techniques of its construction are characteristic of the end of the Muromachi period.[6]

- Bronze Bell, Silla, with an overall height of 147.0 cm and a diameter of 78.3 cm is the largest Korean bell in Japan. The body is long and smooth, with a bulge on the waist, and a slightly squeezed rim. The body has lotus petal and cloud decorations with four celestial maidens flying in the air.[7]

- Horse fittings, Muromachi period. These include a saddle, harness and stirrups with an old bronze peony arabesque decoration, in the style of the Tang dynasty, used for festivals and ceremonies. The set was a donation by Ouchi Yoshitaka.[8]

- Horaku Hyakushu Waka Strip, dated 1495. Sōgi, a leading figure in renga poetry, came to Nagato twice (1480 and 1489) under the protection of Ōuchi Masahiro, where he played a major role in editing the Shinsen Tsukubashū. He donated a strip of poetry with 30 works by famous people, including Sanjōnishi Sanetaka, Emperor Go-Kashiwabara, and others in a cedar box, It was later divided into individual works and placed in a lacquer box by Mōri Hidemoto.[9]

Gallery

Romon

Romon_Haiden.JPG.webp) Haiden

Haiden 1st Torii

1st Torii

References

- Shibuya, Nobuhiro (2015). Shokoku jinja Ichinomiya Ninomiya San'nomiya (in Japanese). Yamakawa shuppansha. ISBN 978-4634150867.

- Yonei, Teruyoshi. "Aramitama". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Yoshiki, Emi (2007). Zenkoku 'Ichinomiya' tettei gaido (in Japanese). PHP Institute. ISBN 978-4569669304.

- Okada, Shoji (2014). Taiyō no chizuchō 24 zenkoku 'Ichinomiya' meguri (in Japanese). Heibonsha. ISBN 978-4582945614.

- "住吉神社本殿" [Sumiyoshi Jinja Honden] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "住吉神社拝殿" [Sumiyoshi Jinja Haiden] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "銅鐘" [Dosho] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "金銅牡丹唐草透唐鞍" [Gold bronze arabesque saddle] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "住吉社法楽百首和歌短冊(明応四年十二月)" [Sumiyoshi-sha Horaku Hyakushu Waka Strip] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.