Swamp eel

The swamp eels (also written "swamp-eels") are a family (Synbranchidae) of freshwater eel-like fishes of the tropics and subtropics.[4] Most species are able to breathe air and typically live in marshes, ponds and damp places, sometimes burying themselves in the mud if the water source dries up. They have various adaptations to suit this lifestyle; they are long and slender, they lack pectoral and pelvic fins, and their dorsal and anal fins are vestigial, making them limbless vertebrates. They lack scales and a swimbladder, and their gills open on the throat in a slit or pore. Oxygen can be absorbed through the lining of the mouth and pharynx, which is rich in blood vessels and acts as a "lung".

| Swamp eels | |

|---|---|

| |

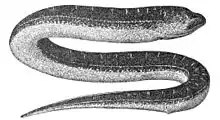

| Monopterus albus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Synbranchiformes |

| Suborder: | Synbranchoidei Boulenger, 1904[1] |

| Family: | Synbranchidae Bonaparte, 1835[2] |

| Type species | |

| Synbranchus marmoratus Bloch, 1795[3] | |

| Genera | |

|

Macrotrema | |

Although adult swamp eels have virtually no fins, the larvae have large pectoral fins which they use to fan water over their bodies, thus ensuring gas exchange before their adult breathing apparatus develops. When about a fortnight old they shed these fins and assume the adult form. Most species of swamp eel are hermaphrodite, starting life as females and later changing to males, though some individuals start life as males and do not change sex.

In the Jiangnan region of China, swamp eels are eaten as a delicacy, usually cooked as part of a stir-fry or casserole.

It is known as Kusia (কুচিয়া) in Assam and Bangladesh. It is considered a delicacy and cooked with curry as part of Assamese cuisine.

Description

The marbled swamp eel, Synbranchus marmoratus, has been recorded at up to 150 cm (59 in) in length,[5] while the Bombay swamp eel, Monopterus indicus, reaches no more than 8.5 cm (3.3 in).

Swamp eels are almost entirely finless; the pectoral and pelvic fins are absent, the dorsal and anal fins are vestigial, reduced to rayless ridges, and the caudal fin ranges from small to absent, depending on species. Almost all of the species lack scales. The eyes are small, and in some cave-dwelling species, they are beneath the skin, so the fish is blind. The gill membranes are fused, and the gill opening is either a slit or pore underneath the throat. The swim bladder and ribs are also absent. These are all believed to be adaptations for burrowing into soft mud during periods of drought, and swamp eels are often found in the mud underneath a dried-up pond.[5]

Most of the species can breathe air, allowing them to survive in low-oxygenated water, and to migrate overland between ponds on wet nights. The linings of the mouth and pharynx are highly vascularised, acting as primitive but efficient lungs. Although swamp eels are not themselves related to amphibians, this lifestyle may well resemble those of the fish from which the land animals evolved during the Devonian period.[5]

Although the adults are virtually finless, the larvae are born with greatly enlarged pectoral fins. The fins are used to propel streams of oxygenated water from the surface along the larva's body. The skin of the larva is thin and vascularised, allowing it to extract oxygen from this stream of water. As the fish grows, the adult air-breathing organ begins to develop, and it no longer requires the fins. At the age of about two weeks, the larva suddenly sheds the pectoral fins, and takes on the adult form.[5]

Most species are protogynous hermaphrodites, that is, most individuals begin life as females, but later change into males. This typically occurs around four years of age, although a small number of individuals are born male and remain so throughout their lives.[5]

Taxonomy

The family Synbranchidae is divided into four gerera as follows:[6]

- genus Macrotrema Regan, 1912

- genus Ophisternon McClelland, 1844

- genus Synbranchus Bloch, 1795

- genus Monopterus Lacepède, 1800

- genus Rakthamichthys Britz, Dahanukar, Standing, Philip, Kumar & Raghavan, 2020

- genus Typhlosynbranchus Pellegrin, 1922

In cooking

In Indonesia swamp eel is called belut, and are commonly harvested from water ponds of rice paddies and become the protein source for rural population in Indonesia. Swamp eel is usually stir fried served with sambal hot chili sauce as belut penyet, curried, or deep fried to achieve crispy texture as kripik belut.[7]

In the Jiangnan region of China, swamp eels are a delicacy, usually cooked in stirfries or casseroles. The recipe usually calls for garlic, scallions, bamboo shoots, rice wine, sugar, starch, and soy sauce with prodigious amounts of vegetable oil. It is popular in the region from Shanghai to Nanjing. The Chinese name in pinyin of this dish is chao shan hu. The name of the swamp eel is shan yu or huang shan.

In Assam swamp eels are considered a delicacy and prepared as curry or dry fry. It is believed there that these are good source of iron and good for blood deficiency.

Conservation status

As of 2021, eleven species were listed by the IUCN as species of special concern: Typhlosynbranchus boueti (Liberian swamp eel), Rakthamichthys indicus (Malabar swamp eel), Rakthamichthys roseni, Rakthamichthys digressus, and Ophichthys hodgarti have been classified as data deficient, meaning that they require more study to determine their conservation status. Ophichthys indicus (Bombay swamp eel) is classified as vulnerable. Ophichthys fossorius (Malabar swampeel), Ophisternon infernale (blind swamp eel), Ophisternon candidum (the blind cave eel), and Ophisternon afrum (Guinea swamp eel) are classified as endangered. Ophichthys desilvai (Desilvai's blind eel) is classified as critically endangered.[8]

On the other side of the endangerment issue, invasive swamp eels in Florida are a major threat to populations of crayfish and some other small species.[9][10]

References

- Robert A. Travers (1985). "A review of the Mastacembeloidei, a suborder of Synbranchoform teleost fish Part 2: Phylogenetic analysis". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 47: 83–151.

- Richard van der Laan; William N. Eschmeyer & Ronald Fricke (2014). "Family-group names of Recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 001–230.

- Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Synbranchus". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- Perdices, A.; Doadrio, I.; Bermingham, E. (November 2005). "Evolutionary history of the synbranchid eels (Teleostei: Synbranchidae) in Central America and the Caribbean islands inferred from their molecular phylogeny". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 460–473. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.01.020. PMID 16223677.

- Liem, Karel F. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 381–383. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- Media, Kompas Cyber (2022-05-11). "7 Cara Masak Belut Bebas Amis, Cocok Jadi Keripik atau Penyetan Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2021-01-29.