Sweden and the euro

Sweden does not currently use the euro as its currency and has no plans to replace the existing Swedish krona in the near future. Sweden's Treaty of Accession of 1994 made it subject to the Treaty of Maastricht, which obliges states to join the eurozone once they meet the necessary conditions.[1][2] Sweden maintains that joining the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), participation in which for at least two years is a requirement for euro adoption, is voluntary,[3][4] and has chosen to remain outside pending public approval by a referendum, thereby intentionally avoiding the fulfilment of the adoption requirements.

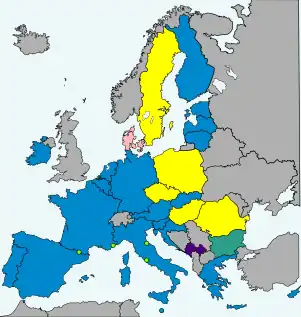

- European Union member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

Status

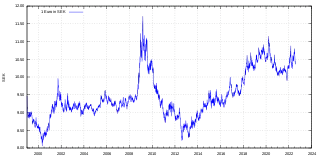

Sweden joined the European Union in 1995 and its accession treaty has since obliged it to adopt the euro once the country is found to comply with all the convergence criteria. However, one of the requirements for eurozone membership is two years' membership of ERM II, and Sweden has chosen not to join this mechanism, which would peg the Swedish currency to the euro ±2.25%. The Swedish krona (SEK) floats freely alongside other currencies. Most of Sweden's major parties believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum.

Olli Rehn, the EU commissioner for economic affairs, has said that it is up to Swedish people to decide when to adopt the euro.[5] However, the European Union is committed to European political integration through a single monetary unit, and European and international pressure for remaining nationalized currencies to be abolished persists.

Despite this, the euro can be used to pay for goods and services in some places in Sweden. (See below.)

Sweden meets four of five conditions for joining the euro as of June 2022. The table below gives further details:

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[6][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[7] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[8][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[9] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[10] | ERM II member[11] | Change in rate[12][13][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

None open (as of 31 March 2012) | Min. 2 years (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2011) |

Max. 5.80%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Yes[14][15] (as of 31 Mar 2012) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2011)[16] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[16] | |||||||

| 1.3% | None | No | 5.3% | 2.23% | No | |||

| -0.3% (surplus) | 38.4% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2012) |

Max. 5.5%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Yes[17][18] (as of 30 Apr 2013) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2012)[19] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[19] | |||||||

| 0.8% | None | No | 3.6% | 1.59% | Unknown | |||

| 0.5% | 38.2% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2013) |

Max. 6.2%[nb 12] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Yes[20][21] (as of 30 Apr 2014) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2013)[22] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[22] | |||||||

| 0.3% | None | No | 0.6% | 2.24% | No | |||

| 1.1% | 40.6% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 13] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 14] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

None open (as of 18 May 2016) | Min. 2 years (as of 18 May 2016) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2015) |

Max. 4.0%[nb 15] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

Yes[23][24] (as of 18 May 2016) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2015)[25] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[25] | |||||||

| 0.9% | None | No | -2.8% | 0.8% | No | |||

| 0.0% | 43.4% | |||||||

| 2018 ECB Report[nb 16] | Reference values | Max. 1.9%[nb 17] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 18] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[26][27] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[28] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[28] | |||||||

| 1.9% | None | No | -1.8% | 0.7% | No | |||

| -1.3% (surplus) | 40.6% | |||||||

| 2020 ECB Report[nb 19] | Reference values | Max. 1.8%[nb 20] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

None open (as of 7 May 2020) | Min. 2 years (as of 7 May 2020) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2019) |

Max. 2.9%[nb 21] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

Yes[29][30] (as of 24 March 2020) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2019)[31] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2019)[31] | |||||||

| 1.6% | None | No | -3.2% | -0.1% | No | |||

| -0.5% (surplus) | 35.1% | |||||||

| 2022 ECB Report[nb 22] | Reference values | Max. 4.9%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

None open (as of 25 May 2022) | Min. 2 years (as of 25 May 2022) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2021) |

Max. 2.6%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

Yes[32][33] (as of 25 March 2022) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2021)[32] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2021)[32] | |||||||

| 3.7% | None | No | 3.2% | 0.4% | No | |||

| 0.2% | 36.7% | |||||||

- Notes

- The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[14]

- Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[14]

- The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[14]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[17]

- Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[17]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[20]

- Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states, with Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus excluded as outliers.[20]

- Latvia, Ireland and Portugal were the reference states.[20]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[23]

- Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states, with Cyprus and Romania excluded as outliers.[23]

- Slovenia, Spain and Bulgaria were the reference states.[23]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[26]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[26]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[26]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2020.[29]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[29]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[29]

- Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2022.[32]

- France, Finland, and Greece were the reference states.[32]

History

Early monetary unions in Sweden (1873–1914)

On 5 May 1873 Denmark with Sweden fixed their currencies against gold and formed the Scandinavian Monetary Union. Prior to this date Sweden used Swedish riksdaler. In 1875 Norway joined this union. An equal valued krona of the monetary union replaced the three legacy currencies at the rate of 1 krona = ½ Danish rigsdaler = ¼ Norwegian speciedaler = 1 Swedish riksdaler. The new currency (krona) became a legal tender and was accepted in all three countries – Denmark, Sweden and Norway. This monetary union lasted until 1914, when it was brought to an end by World War I. As of 2014, the names of the currencies in each country have remained unchanged ("krona" in Sweden, "krone" in Norway and Denmark).

Joining the European Union

The Swedish European Union membership referendum of 1994 approved—with a 52% majority—the Accession Treaty[37] and in 1995 Sweden joined the EU. According to the treaty Sweden is obliged to adopt the euro once it meets convergence criteria.

2003 referendum

A referendum held in September 2003 saw 55.9 percent vote against membership of the eurozone. As a consequence, Sweden decided in 2003 not to adopt the euro for the time being. If they had voted in favour, Sweden would have adopted the euro on 1 January 2006.[38]

A majority of voters in Stockholm County voted in favour of adopting the euro (54.7% "yes", 43.2% "no"). In Skåne County the people voting "yes" (49.3%) outnumbered the people voting "no" (48.5%), although the invalid and blank votes resulted in no majority for either option. In all other polls in Sweden, the majority voted no.[39][40]

Usage today

Some shops, hotels and restaurants may accept euros, often limited to notes and giving change in Swedish Krona. This is especially common in some border cities. Shops especially oriented towards foreign tourists are more likely to accept foreign currencies (such as the euro) than other shops. Payphones in Sweden were able to accept coins in both Swedish kronor and euro since the year 2000.[41] The last payphone was dismantled in 2015.

Official currency status

Matters such as official currency status and legal tender issues are decided by the Swedish parliament, and the euro is not an official currency of any part of Sweden. Nevertheless, politicians from some municipalities (see below) have claimed that the euro is an official currency of their municipalities. This means that the municipality has made an agreement with many shops that they should accept euros (in cash and credit cards).[42] However this is not mandatory for the stores and the status as "official currency" is mostly a marketing device rather than a legal mandate.

Haparanda

The only Swedish city near the eurozone is Haparanda,[43] where almost all stores accept euros as cash and often display prices in euros. Haparanda has become an important shopping city with the establishment of IKEA and other stores. 200,000 Finns live within 150 km distance.

Some municipalities, especially Haparanda, wanted to have the euro as a legally official currency,[44] and, for example, contract salaries in euros to employees from Finland. However, this is illegal due to tax laws and salary rules. (The actual payment can be in euro, handled by the bank, but the salary contract and the tax documentation must be in kronor).

Haparanda's budget is presented in both currencies.[45] Haparanda has a close cooperation with the neighbour city of Tornio, Finland.

Höganäs

The town of Höganäs claimed to have adopted the euro for shops on 1 January 2009.[46] From that date, all residents can use either kronor or euro in restaurants and shops, as well as in payments of rent and bills. Dual pricing is used at many places and ATMs dispense either currency without additional charge (the latter is law all over Sweden). Around 60 percent of stores in the town are reported to have signed up to the scheme and local banks have developed guidelines to accept euro deposits.[47] This decision was approved and agreed by municipality of Höganäs.[48] Höganäs has developed a special euro logo for the city. It is not a law in Höganäs, just a recommendation. This has been a rather successful PR coup, with good coverage in newspapers, and it has been mentioned also in foreign newspapers.[49]

Helsingborg, Landskrona and Malmö

Some shops accept euros, and price tags in euros exist in some tourist oriented shops, as in more cities in Sweden. Acceptance of and price tags in Danish kroner are probably more common. Euro (and Danish krone) are typically accepted at 24-hour open petrol stations, international fast food chains and at hotels.

Pajala and Övertorneå

The Pajala and Övertorneå municipalities have borders to Finland (and thus to the eurozone). The euro is often accepted in shops and sometimes shown on price tags,[50] but there is no official adoption of the euro from the municipality point of view. There was a rejected political proposal to officially adopt the euro in Pajala.[51][52]

Sollentuna

There was a political proposal in June 2009 from a party in the Sollentuna Municipality, that the municipality should adopt the euro as its parallel currency in 2010.[53][54]

Stockholm

Stockholm is the most important tourist city in Sweden, measured as the number of nights spent by tourists. Some tourist-oriented shops accept euros, although there is no official policy from the municipality. Taxi services in Stockholm can be paid in euros.[55] In 2009 there was a rejected political proposal to officially introduce the euro in Stockholm.[53]

Cash machines

Some cash machines can dispense foreign currency. Usually euros, but sometimes British pounds, US dollars, Danish kroner or Norwegian kroner can be dispensed instead. All of these cash machines also dispense Swedish kronor. Most of these cash machines are located in major cities, international airports and border areas.

Presence of the euro in Swedish law and bank system

The euro is present in some elements of Swedish law, based on EU directives. For example, an EU directive states that all transactions in euros inside the EU shall have the same fees as euro transactions within the country concerned.[56][57] The Swedish government has made an amendment[58] which states that the directive also applies to krona-based transactions. This means, for example, that euros can be withdrawn without fees from Swedish banks at any ATM in the eurozone, and that krona- and euro-based transfers to bank accounts in the European Economic Area can be done over the internet without a sending fee. The receiving banks can still sometimes charge a fee for receiving the payment, though, although the same EU directive typically makes this impossible for euro-based transfers to eurozone countries. This is different from, for example, Denmark where banks are required to set the price for international euro transactions within the European Economic Area to the same price as for domestic Danish euro transactions (which does not have to be the same as the price for domestic Danish krone transactions). However, banks in Sweden still decide the exchange rate, and so are able to continue charging a small percentage for exchanging between kronor and euros when using card payments.

It is also now possible for limited companies (companies limited by shares) to have their accounts and share capital denominated in euros.[59][60] The law about money laundering is based on an EU directive and sets a limit of €5,000 for cash transactions to be investigated regarding origin of money and receipts to be claimed, by companies such as banks, car dealers etc.[61]

Many more Swedish laws today include amounts in euro due to EU directives.[62]

Plans

Most major political parties in Sweden, including the formerly governing coalition Alliance for Sweden (except the Center Party) and the currently governing Moderate Party, which won the 2022 election, are in principle in favour of introducing the euro.

Tommy Waidelich, then economic spokesperson for the Social Democratic Party, ruled out Swedish eurozone membership for the foreseeable future in August 2011.[63]

The newspaper Sydsvenska Dagbladet claimed on 26 November 2007 (a few days after the former Danish Prime Minister, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, had announced plans to hold another referendum on abolishing Denmark's opt-outs including the opt-out from the euro) that the question of another euro referendum would be one of the central issues of the 2010 election in Sweden.[64] Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt stated in December 2007 that when more neighbours use the euro, it will be more visible that Sweden does not.[65]

Swedish politician Olle Schmidt in an interview with journalists from the European Parliament 2008 when asked when Sweden will have good reasons to adopt the euro, he said "When the Baltic countries join the euro, the whole Baltic Sea will be surrounded by euro coins. Then the resistance will drop. I hope for a referendum in Sweden in 2010."[66] Lithuania adopted euro as the last Baltic country in 2015, without creating much debate in Sweden.

The social democratic party leader Mona Sahlin at the time has 2008 stated that a new referendum will not occur in the period 2010–2013, because the 2003 referendum still counts.[67]

2009 European elections

During the election campaign for the European Parliament elections, Liberal People's Party and Christian Democrats expressed interest in holding a second referendum on euro adoption. However, the Moderate Party and Centre Party thought that the time was ill-chosen.[68]

Economic research

A 2009 economic study from J. James Reade (Oxford) and Ulrich Volz (German Development Institute) on the possible entry of Sweden in the eurozone has found that it would be likely to have a positive effect. The study of the evolution of the Swedish money market rates shows that they closely follow the euro rates, even during times of economic crisis. This shows that Sweden would not lose in terms of monetary policy autonomy, as the Swedish Central Bank already closely follows the rates set by the European Central Bank. When adopting the euro, Sweden would swap this autonomy on paper for a real influence on the European monetary policy thanks to the gaining of a seat in the ECB's governing council. Overall, the study concludes that "staying outside of the eurozone implies forgone benefits that Sweden, a small open economy with a sizable and internationally exposed financial sector, would enjoy from adopting an international currency."[69]

Opinion polls

Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.[70] The polls have generally showed a stable support for the "no" alternative, except some polls in 2009 which showed a support for "yes". Since 2010 opinion polls have shown a strong support for "no".

Results

Polls on the question whether Sweden should abolish the krona and join the euro are regularly carried out, usually by the state statistics agency Statistics Sweden (SCB). The results are always published in the press or online.

| Pollster | Dates conducted |

Date published |

Sample size |

Yes | No | Unsure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCB[71][72] | May 2004 | 18 Jun 2004 | 7,046[71] | 37.8% | 50.9% | 11.3% |

| SCB[72][73] | Nov 2004 | 15 Dec 2004 | 6,919[73] | 37.3% | 48.6% | 14.3% |

| SCB[72][74] | May 2005 | 21 Jun 2005 | 6,985[74] | 39.4% | 46.4% | 14.2% |

| SCB[72][75] | Nov 2005 | 20 Dec 2005 | 6,980[75] | 36.1% | 49.4% | 14.5% |

| SCB[72][76] | May 2006 | 20 Jun 2006 | 6,870[76] | 38.1% | 48.7% | 13.2% |

| SCB[72][77] | Nov 2006 | 19 Dec 2006 | 7,012[77] | 34.7% | 51.5% | 13.8% |

| Skop[78] | ? | 24 Mar 2007 | ? | 37% | 60% | 3% |

| SCB[72][79] | May 2007 | 19 Jun 2007 | 6,932[79] | 33.3% | 53.8% | 13% |

| SCB[72][80] | Nov 2007 | 18 Dec 2007 | 6,922[80] | 35.0% | 50.8% | 14.2% |

| SCB[72][81] | May 2008 | 17 Jun 2008 | 6,817[81] | 34.6% | 51.7% | 13.7% |

| SCB[72][82] | Nov 2008 | 16 Dec 2008 | 6,687[82] | 37.5% | 47.5% | 15% |

| SCB[83] | ? | Dec 2008 | 1,006 | 44% | 48% | 7% |

| Skop[84] | ? | 1 Mar 2009 | ? | 45% | 51% | 4% |

| Sifo[85] | ? | 19 Apr 2009 | ? | 47% | 45% | 8% |

| Novus Opinion[86] | ? | 12 May 2009 | 1,000 | 51% | 49% | 0% |

| Novus Opinion[87] | ? | 25 May 2009 | 1,000 | 47% | 44% | 9% |

| SCB[72][88] | May 2009 | 23 Jun 2009 | 6,506[88] | 42.1% | 42.9% | 15.1% |

| SCB[72][89] | Nov 2009 | 15 Dec 2009 | 6,398[89] | 43.8% | 42.0% | 14.2% |

| Demoskop[90] | ? | 9 Apr 2010 | 1,004 | 37% | 55% | 8% |

| SCB[72][91] | May 2010 | 15 Jun 2010 | 6,135[91] | 27.8% | 60% | 12.2% |

| SCB[72][92] | Nov 2010 | 14 Dec 2010 | 6,192[92] | 28.9% | 58.2% | 12.9% |

| SCB[72][93] | May 2011 | 15 Jun 2011 | 6,147[93] | 24.1% | 63.7% | 12.2% |

| SCB[94] | Nov 2011 | 13 Dec 2011 | 5,907[94] | 11.2% | 80.4% | 8.4% |

| SCB[95] | May 2012 | 11 Jun 2012 | 5,473[95] | 13.6% | 77.7% | 8.7% |

| SCB[96] | Nov 2012 | 12 Dec 2012 | 5,479[95] | 9.6% | 82.3% | 8.0% |

| SCB[97] | May 2013 | 11 Jun 2013 | 5,098[97] | 10.9% | 81.4% | 7.7% |

| SCB[98] | Nov 2013 | 11 Dec 2013 | 5,267[98] | 12.6% | 78.3% | 9.2% |

| SCB[99] | May 2014 | 10 Jun 2014 | 4,757[99] | 13.1% | 77.4% | 9.6% |

| Eurobarometer[100] | Jun 2014 | Jul 2014 | ? | 19% | 77% | 4% |

| SCB[101] | Nov 2014 | 10 Dec 2014 | 5,072[101] | 13.2% | 76.9% | 10.0% |

| Eurobarometer[102] | Nov 2014 | Dec 2014 | ? | 23% | 73% | 4% |

| Eurobarometer[103] | Apr 2015 | May 2015 | ? | 32% | 66% | 2% |

| SCB[104] | May 2015 | 11 Jun 2015 | 6,067 | 15.3% | 74.9% | 9.7% |

| SCB[105] | Nov 2015 | 9 Apr 2015 | 4,972 | 14.0% | 75.5% | 10.5% |

| Eurobarometer[106] | Apr 2016 | May 2016 | 1000 | 30% | 68% | 2% |

| SCB[105] | May 2016 | 3 Jun 2016 | 4,838 | 15.0% | 74.1% | 10.9% |

| SCB[107] | Nov 2016 | 6 Dec 2016 | 5,021 | 15.8% | 72.0% | 12.2% |

| Eurobarometer[108] | Apr 2017 | May 2017 | 1001 | 35% | 62% | 3% |

| SCB[109] | May 2017 | 7 Jun 2017 | 4,808 | 16.5% | 70.6% | 12.9% |

| SCB[110] | Nov 2017 | 8 Dec 2017 | 4,715 | 17.1% | 69.9% | 13.0% |

| Eurobarometer[111] | Apr 2018 | May 2018 | 1001 | 40% | 56% | 4% |

| SCB[112] | May 2018 | 11 Jun 2018 | 4,632 | 20.1% | 66.0% | 14.0% |

| SCB[113] | Nov 2018 | 7 Dec 2018 | 4,721 | 18.6% | 68.0% | 13.4% |

| Eurobarometer[114] | Apr 2019 | Jun 2019 | 1000 | 36% | 60% | 4% |

| SCB[115] | May 2019 | 11 Jun 2019 | 4,506 | 19.3% | 66.0% | 14.7% |

| SCB[116] | Nov 2019 | 10 Dec 2019 | 4,645 | 21.4% | 62.5% | 16.0% |

| Eurobarometer[117] | May 2020 | Jul 2020 | 1003 | 35% | 63% | 3% |

| SCB[118] | May 2020 | 11 Jun 2020 | 4,888 | 20.3% | 64.3% | 15.4% |

| SCB[119] | Nov 2020 | 8 Dec 2020 | 4 692 | 19.2% | 64.3% | 16.5% |

| Eurobarometer[120] | May 2021 | Jul 2021 | 1016 | 42% | 56% | 2% |

| SCB[121] | May 2021 | 8 Jun 2021 | 4 656 | 20.4% | 63.2% | 16.5% |

| Eurobarometer[122] | Apr 2022 | Jul 2022 | 1039 | 45% | 52% | 3% |

| Eurobarometer[123] | Apr 2023 | Jun 2023 | 1039 | 54% | 43% | 2% |

- SCB polling question: If a referendum were held today to replace the Swedish krona as a currency, would you vote "yes" or "no" with regard to introducing the euro as Sweden's currency? Swedish: Om vi idag skulle ha folkomröstning om att ersätta kronan som valuta, skulle du då rösta Ja eller Nej till att inför euron som valuta i Sverige?

- Eurobarometer question: Generally speaking, are you personally more in favour or against the idea of introducing the euro in Sweden?

- Public support for introducing the euro in Sweden according to Eurobarometer polls

Critique of polling questions

How the polling questions are phrased has a major impact on how people respond. The SCB polling question tends to measure if the electorate favor voting yes/no for Sweden to adopt the euro as soon as possible. However, polls conducted by TNS Polska in Poland showed that this question finds a large group of supporters of euro adoption would vote no to adopting the euro as soon as possible, but that a majority of them would vote yes if asked whether or not the state should adopt the euro ten years from now.

Swedish euro coins

There are no designs for potential Swedish euro coins. It was reported in the media that when Sweden changed the design of the 1-krona coin in 2001 it was in preparation for the euro. A newer portrait of the king was introduced. The 10-kronor coin already had a similar portrait. This in fact is from a progress report by the Riksbank on possible Swedish entry into the euro, which states that the lead in time for coin changeover could be reduced through using the portrait of King Carl XVI Gustaf introduced on the 1- and 10-kronor coins in 2001 as the national side on Swedish 1- and 2 euro coins.[124]

Only the national bank can issue legal tender coins according to Swedish law. Some private collection mint companies have produced Swedish euro coins, claiming that they are copies of test coins made by the Riksbank.[125]

Membership of the European Central Bank's Banking Union

Since the rise in resolution fund fees for Swedish banks to protect against banking failures in 2017,[126] resulting in the move of the headquarters of the biggest bank in Sweden and the entire Nordic region, Nordea, from Stockholm to the Finnish capital Helsinki, which lies within the eurozone and therefore also within the European Central Bank's Banking Union, there has been discussion about Sweden joining the banking union. Nordea's chairman of the board, Björn Wahlroos, stated that the bank wanted to put itself "on a par with its European peers" in justifying the relocation from Stockholm to Helsinki.[127]

The main aim for joining the Banking Union is to protect Swedish banks against being "too big to fail". Sweden's Financial Markets Minister Per Bolund has said that the country is conducting a study on joining, which is planned to be completed by 2019.[128][129] Critics argue that Sweden will be disadvantaged by joining the banking union because it does not have any voting rights, as it is not a member of the eurozone. Swedish former Finance Minister and former Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson stated: "You can't ignore the fact that the decision-making can be a little problematic for countries not in the eurozone."[127]

See also

- Economy of Sweden under Economic and Monetary Union and Trade unions

- Enlargement of the eurozone

- Sweden in the European Union

References

- EU4Journalists.eu Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Economic and Monetary Union and the Euro eu4journalists, accessed 8 January 2008

- "European Commission > Economic and Financial Affairs > The euro > Your country and the euro > Sweden and the euro". Ec.europa.eu. 30 May 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Sverige sa nej till euron" (in Swedish). Swedish Parliament. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Information on ERM II". European Commission. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- "Summary of hearing of Olli Rehn – Economic and Monetary Affairs (Hearings – Institutions – 12-01-2010 – 09:39)". European Parliament. 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Olle Schmidt (ALDE, SE) inquired whether Sweden could still stay out of the Eurozone. Mr Rehn replied that it is up to the Swedish people to decide on the issue.

- "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report - May 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report 2020" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report - June 2020". European Commission. June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2020". European Commission. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report June 2022" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Convergence Report 2022" (PDF). European Commission. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "European Union Agreement Details". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- "Heikensten: The Riksbank and the euro". Sveriges Riksbank. 17 June 2003. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Sweden. Euro Referendum 2003". Electoral Geography. 10 September 2003. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Riksöversikten" (in Swedish). Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- Lars Epstein (27 April 2016). "Den gamla telefonkiosken, vart har den tagit vägen? Till Spånga!" (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

och så här såg dem modernaste och sista ut (den så kallade dammsugaren) som introducerades 2000 och var bruk till 2015. Den hade myntinkast för både tiokronor och euro och gick också att använda med kreditkort. En epok är över.

- "Facts about card acceptance package from the bank, read about "Multicurrency"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2005. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Near could be defined as within 50 km or 30 minutes' driving. Norrtälje is 80 km and more than two hours travel from Mariehamn. Regarding the definition of "city" see Stad (Sweden) and List of traditional Swedish cities (in Swedish).

- "Swedish mayor wants to abolish the kronor". EUobserver. 20 December 2001. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "The introduction of euro banknotes and coins: one year on". Europa. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Bjällstrand, Richard (3 January 2009). "Delade meningar om euro hos handlare". Helsingborgs Dagblad (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Vinthagen Simpson, Peter (2 January 2009). "Swedish town adopts euro". The Local. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Rantala, Anette (5 September 2008). "Euron blir gångbar valuta i Höganäs". Helsingborgs Dagblad (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Buchanan, Michael (29 December 2008). "Swedish town aims to be 'euro-city'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Example: Pajala badhus

- "Sammanträdesprotokoll. Motion införande av euro-zon i Pajala" (PDF).

- "Euron bör bli ny valuta i Pajala". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Anna Gustafsson (14 June 2009). "SVD.se". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). SVD.se. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Sollentuna.se" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Taxijakt.seTaxiStockholm.se TakiKurir.se Taxi020.se Kontela.se

- "Lag (1999:268) om betalningsöverföringar inom Europeiska ekonomiska samarbetsområdet" (in Swedish). Sveriges riksdag. 12 May 1999. Retrieved 26 December 2008. implementing Directive 97/5/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 1997 on cross-border credit transfers

- "EUR-Lex – 32009R0924 – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- "Lag (2002:598) om avgifter för vissa gränsöverskridande betalningar" (in Swedish). Sveriges riksdag. 13 June 2002. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- "Lag (2000:46) om omräkningsförfarande vid beskattning för företag som har sin redovisning i euro, m.m." (in Swedish). Sveriges riksdag. 10 February 2000. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Aktiebolagslag (2005:551)" (in Swedish). Sveriges riksdag. 16 June 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Lag (2017:630) om åtgärder mot penningtvätt och finansiering av terrorism Svensk författningssamling 2017:2017:630 t.o.m. SFS 2021:517 – Riksdagen". riksdagen.se.

- "2883 träffar för 'euro'". lagen.nu.

- "Social Democrats: Sweden should stay outside the euro (spokesperson:Waidelich)". Stockholmnews.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Denmark and Sweden on the path to the euro?". Courrier International. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "Glöm euron, Reinfeldt" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "The strengthening Euro – is it good or bad for Europe's economy?". European Parliament. 2 July 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Intresse för euro i Sverige och Danmark" (in Swedish). Rundradion Ab. 2 November 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Erika Svantesson (9 May 2009). "Alliansen splittrad i eurofrågan" [Alliance fragmented over euro question]. DN.se (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter AB. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "Economics.ox.ac.uk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Glöm euron, Reinfeldt" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- "EU- och Euro-sympatier i maj 2004" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 18 June 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EMU-/eurosympatier 1997–2010" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i november 2004" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 15 December 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i maj 2005" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 21 June 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i november 2005" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 20 December 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i maj 2006" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i november 2006" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 19 December 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "Svenskar fortsatt EMU-skeptiska". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 24 March 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i maj 2007: Nej till euron vid folkomröstning i maj" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och euro-sympatier i november 2007: Minskat motstånd till euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 18 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i maj 2008: Fortsatt motstånd till euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i november 2008: Minskat motstånd till euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "Swedish support for joining eurozone swells as krona shrivel". Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

- "Uppåt för S och M i EU-mätning" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2 March 2009.

- "More Swedes support joining euro zone: latest poll". 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009.

- "Majoritet vill ha ny euroomröstning" (in Swedish). 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012.

- "Majoritet vill införa euron". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 25 May 2009.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i maj 2009: Ökat stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i november 2009: Stödet för euron ökar" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 15 December 2009. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "Rekordhögt motstånd mot euron" (in Swedish). 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i maj 2010: Klart minskat stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 August 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och Eurosympatier, november 2010: Fortsatt svagt stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 14 December 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i maj 2011: Klart minskat stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i november 2011: Kraftigt minskat stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "EU- och eurosympatier i maj 2012: Något ökat stöd för euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Rekordlågt stöd för Euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Fortsatt svagt stöd för Euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Minskat motstånd mot euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Oförändrad opinion kring euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "PUBLIC OPINION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION" (PDF). Eurobarometer. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Oförändrad opinion kring euron" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "PUBLIC OPINION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION" (PDF). Eurobarometer. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- "Eurobarometer: A majority in four newer EU Member States want the euro – European Commission". ec.europa.eu.

- "More people positive to the euro". Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden 2015" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden November 2016" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden May 2017" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden November 2017" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the common currency". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden May 2018" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "EMU/Euro preferences in Sweden November 2018" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "General public in seven EU countries not yet having adopted the euro". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "Political party preferences in May 2019". Statistics Sweden. 11 June 2019.

- "Political party preferences in November 2019". Statistics Sweden. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Introduction of the euro in the Member States that have not yet adopted the euro". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "Political party preferences in May 2020". Statistics Sweden. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Political party preferences in November 2020". Statistics Sweden. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- "Introduction of the euro in the MS that have not yet adopted the common currency". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "Political party preferences in May 2021". Statistics Sweden. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- "Introduction of the euro in the MS that have not yet adopted the common currency". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Introduction of the euro in the MS that have not yet adopted the common currency - Spring 2023". Eurobarometer. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- "The Euro in the Swedish Financial Sector – Banknotes and Coins" (PDF). Sveriges Riksbank. September 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Swedish Euro Coins?". Chard Limited. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Sweden drops plans for bank tax, proposes higher resolution fund fee". Reuters. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Should Sweden join the European banking union?". The Local Sweden. 8 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Goksör, Joakim (11 July 2017). "Förslag om bankunion med EU om två år – Nyheter (Ekot)". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Sweden considers joining EU's banking union – TT news agency". Reuters. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

External links

- Central bank

- Central bank (in Swedish)