Opt-outs in the European Union

In general, the law of the European Union is valid in all of the twenty-seven European Union member states. However, occasionally member states negotiate certain opt-outs from legislation or treaties of the European Union, meaning they do not have to participate in certain policy areas. Currently, three states have such opt-outs: Denmark (two opt-outs), Ireland (two opt-outs) and Poland (one opt-out). The United Kingdom had four opt-outs before leaving the Union.

This is distinct from the enhanced cooperation, a measure introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam, whereby a minimum of nine member states are allowed to co-operate within the structure of the European Union without involving other member states, after the European Commission and a qualified majority have approved the measure. It is further distinct from Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification and permanent acquis suspensions, whose lifting is conditional on meeting certain benchmarks by the affected member states. It is also distinct from the delayed entrance into some areas of cooperation which new members are experiencing. These areas include the Schengen Agreement and the Eurozone, and the delay can last for many years and even decades.

Current opt-outs

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

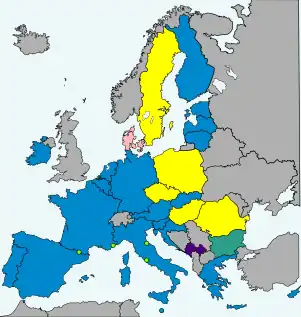

As of 2023, three states have formal opt-outs from a total of four policy areas.

Summary table

| Country | Number of opt‑outs | Policy domain and area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) | Area of freedom, security and justice (AFSJ) | ||||

| Eurozone | Charter of Fundamental Rights enforcement | Schengen Area | Remainder of AFSJ | ||

| 2 | Opt-out[lower-alpha 1] | No opt-out | Intergovernmental agreement | Opt-out | |

| 2 | No opt-out | No opt-out | Opt-out (opt-in) |

Opt-out (opt-in) | |

| 1 | No implementation[lower-alpha 2] | Opt-out[lower-alpha 3] | No opt-out | No opt-out | |

| |||||

Economic and Monetary Union stage III (Eurozone) – Denmark

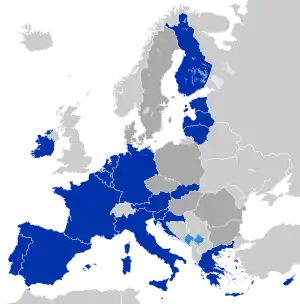

- European Union member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

All member states other than Denmark have either adopted the euro or are legally bound to do so. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 included protocols on the UK[1] (a member state at the time) and Denmark giving them opt-outs with the right to decide if and when they would join the euro. Denmark subsequently notified the Council of the European Communities of their decision to opt out of the euro, and this was included as part of the 1992 Edinburgh Agreement, a Decision of Council, reached following the Maastricht Treaty's initial rejection in a 1992 Danish referendum. The purpose of the agreement was to assist in its approval in a second referendum, which it did. The Danish decision to opt out was subsequently formalized in an amended protocol as part of the Lisbon Treaty.

In 2000, the Danish electorate voted against joining the euro in a referendum by a margin of 53.2% to 46.8% on a turnout of 87.6%.

While the remaining states are all obliged to adopt the euro eventually by the terms of their accession treaties, since membership in the Exchange Rate Mechanism is a prerequisite for euro adoption, and joining ERM is voluntary, these states can ultimately control the timing of their adoption of the euro by deliberately not satisfying the ERM requirement.

Area of freedom, security and justice

Denmark and Ireland have opt-outs from the area of freedom, security and justice in general, while Poland has a partial opt-out from enforcement of the Charter of Fundamental Rights only.

The United Kingdom also had opt-outs in all these policies prior to its withdrawal from the European Union in 2020.

Ireland

Ireland has a flexible opt-out from legislation adopted in the area of freedom, security and justice, which includes all matters previously part of the pre-Amsterdam Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) pillar.[2] This allows it to opt in or out of legislation and legislative initiatives on a case-by-case basis, which it usually did, except on matters related to Schengen acquis.[3]

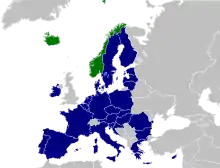

The Schengen Agreement abolished border controls between those of the EC member states which acceded to it. When the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 incorporated it into the EU treaties, Ireland and the United Kingdom (a member state at the time) received opt-outs from implementing the Schengen acquis as they were the only EU member states that had not signed the agreement. The opt-out from the JHA policy area was originally obtained by Ireland and the United Kingdom in a protocol to the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997, and was retained by both with the Treaty of Lisbon.[4] Ireland joined the UK in adopting this opt-out to keep their border with Northern Ireland open via the Common Travel Area (CTA).[1][5][6]

However, the protocol on the Schengen acquis specified that they could request to opt into participating in Schengen measures on a case-by-case basis if they wished, subject to unanimous approval of the other participating states. Ireland initially submitted a request to participate in the Schengen acquis in 2002, which was approved by the Council of the European Union, though not implemented.[7] Prior to the renewal of the CTA in 2011, when the British government was proposing that passports be required for Irish citizens to enter the UK,[8] there were calls for Ireland to join the Schengen Area.[6] However, in response to a question on the issue, Bertie Ahern, the then-incumbent Taoiseach, stated: "On the question of whether this is the end of the common travel area and should we join Schengen, the answer is 'no'."[6][9] The opt-out was criticised in the United Kingdom for hampering the country's capabilities in stopping transnational crime through the inability to access the Schengen Information System.[10]

Following the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union, Ireland is the only member state with an opt-out from the Schengen Agreement. A Council decision in 2020 approved the implementation of the provision on data protection and Schengen Information System to Ireland.[11]

Denmark

In contrast, Denmark has a more rigid opt-out from the area of freedom, security and justice. While the Edinburgh Agreement of 1992 stipulated that "Denmark will participate fully in cooperation on Justice and Home Affairs",[12] the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 included a protocol which exempts it, as a matter of EU law, from participating in these policy areas, which are instead conducted on an intergovernmental basis with Denmark. The protocol on the Schengen acquis and protocol on Denmark of the Treaty of Amsterdam stipulate that Denmark, which had signed an accession protocol the Schengen Agreement, would continue to be bound by the provisions and would have the option to participate in future developments of the Schengen acquis, but would do so on an intergovernmental basis rather than under EU law for the provisions that fell under the Justice and Home Affairs pillar, from which Denmark obtained an opt-out. When a measure is adopted which builds upon the Schengen acquis, Denmark has six months to decide whether to implement it. If Denmark decides to implement the measure, it takes the force of an international agreement between Denmark and the Schengen states. However, the protocol stipulates that if Denmark chooses not to implement future developments of the Schengen acquis, the EU and its member states "will consider appropriate measures to be taken".[13] The exception is the Schengen visa rules. A failure by Denmark to implement a Schengen measure could result in it being excluded from the Schengen Area.[14] A number of other parallel intergovernmental agreements have been concluded between the EU and Denmark to extend to it EU Regulations adopted under the area of freedom, security and justice, which Denmark can't participate in directly due to its opt-out.

In the negotiations of the Lisbon Treaty, Denmark obtained an amendment to the protocol to give it the option to convert its opt-out into a flexible opt-in modelled on the Irish and British opt-outs.[15] The Protocol stipulates that if Denmark exercises this option, then it will be bound by the Schengen acquis under EU law rather than on an intergovernmental basis. In a referendum on 3 December 2015, 53.1% rejected exercising of this option.[16]

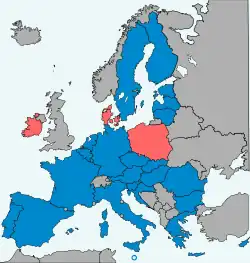

Poland (Charter of Fundamental Rights enforcement only)

Although Poland participates in the area of freedom, security and justice, it has secured along with another then-member state, the United Kingdom, a protocol that clarified how the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, a part of the Treaty of Lisbon, would interact with national law in their countries limiting the extent that European courts would be able to rule on issues related to the Charter if they are brought to courts in Poland.[17] Poland's then ruling party, Law and Justice, mainly noted concerns that it might force Poland to grant homosexual couples the same kind of benefits that heterosexual couples enjoy.[18]

After the Civic Platform won the 2007 parliamentary election in Poland, it announced that it would not opt out from the Charter, leaving the United Kingdom as the only state not to adopt it.[19] However, Donald Tusk, the new Prime Minister and leader of the Civic Platform, later qualified that pledge, stating he would consider the risks before abolishing the opt-out,[20] and on 23 November 2007, he announced that he would not eliminate the Charter opt-out after all (despite the fact that both his party and their coalition partner, the Polish People's Party, were in favour of eliminating it), stating that he wanted to honour the deals negotiated by the previous government and that he needed the support of Law and Justice to gain the two-thirds majority in the Parliament of Poland required to authorise the President to ratify the Treaty of Lisbon.[21] Shortly after the signature of the treaty, the Polish Sejm passed a resolution that expressed its desire to be able to withdraw from the Protocol.[22] Tusk later clarified that he may sign up to the Charter after successful ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon has taken place.[23] However, after the treaty entered into force a spokesperson for the Polish President argued that the Charter already applied in Poland and thus it was not necessary to withdraw from the protocol. He also stated that the government was not actively attempting to withdraw from the protocol.[24] Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Radosław Sikorski, of Civic Platform, argued that the protocol only narrowly modified the charter's application in Poland, and that formally renouncing the opt-out would require a treaty amendment that would need to be ratified by all EU member states.[25] In April 2012, Leszek Miller, leader of the Democratic Left Alliance, stated that he would sign the charter if he comes to power.[26] According to Andrew Duff, British Member of the European Parliament, "A Polish constitutional mechanism has since been devised whereby Poland can decide to amend or to withdraw from the Protocol, and such a possibility remains under review."[27]

Legal guarantees

Several times an EU member state has faced domestic public opposition to the ratification of an EU treaty leading to its rejection in a referendum. To help address the concerns raised, the EU has offered to make a "legal guarantee" to the rejecting state. These guarantees did not purport to exempt the state from any treaty provisions, as an opt-out does. Instead they offered a clarification or interpretation of the provisions to allay fears of alternative interpretations.

Citizenship – Denmark

As part of the 1992 Edinburgh Agreement, Denmark obtained a clarification on the nature of citizenship of the European Union which was proposed in the then yet-to-come-into-force Maastricht Treaty.[28] The Agreement was in the form of a Decision of Council.[29] The part of the agreement, which only applied to Denmark, relating to citizenship was as follows:

The provisions of Part Two of the Treaty establishing the European Community relating to citizenship of the Union give nationals of the Member States additional rights and protection as specified in that Part. They do not in any way take the place of national citizenship. The question whether an individual possesses the nationality of a Member State will be settled solely by reference to the national law of the Member State concerned.

The guarantee to Denmark on citizenship was never incorporated into the treaties, but the substance of this statement was subsequently added to the Amsterdam Treaty and applies to all member states. Article 2 states that:

Citizenship of the Union shall complement and not replace national citizenship.

Irish protocol on the Lisbon Treaty

Following the rejection of the Treaty of Lisbon by the Irish electorate in 2008, a number of guarantees (on security and defence, ethical issues and taxation) were given to the Irish in return for holding a second referendum. On the second attempt in 2009 the treaty was approved. Rather than repeat the ratification procedure, the guarantees were merely declarations with a promise to append them to the next treaty.[30][31]

The member states ultimately decided not to sign the protocol alongside the Croatian accession treaty, but rather as a single document. A draft protocol to this effect[32] was proposed by the European Council and adopted by the European Parliament in April 2012.[33] An Intergovernmental Conference followed on 16 May,[34] and the protocol was signed by all states of the European Union between that date and 13 June 2012.[35] The protocol was planned to take effect from 1 July 2013, provided that all member states had ratified the agreement by then,[36] but it only entered into force on 1 December 2014.[37]

Former opt-outs

Opt-outs of the United Kingdom

During its membership of the European Union, the United Kingdom had five opt-outs from EU legislation (from the Schengen Agreement, the Economic and Monetary Union, the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the area of freedom, security and justice, and the Social Chapter), four of them still in place when it left the Union, the most of any member state.

The Major ministry secured the United Kingdom an opt-out from the protocol on the Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty before it was signed in 1992.[38] The Blair ministry abolished this opt-out after coming to power in the 1997 general election as part of the text of the Treaty of Amsterdam.[39][40]

In the United Kingdom, the Labour government of Tony Blair argued that the country should join the euro, contingent on approval in a referendum, if five economic tests were met. However, the assessment of those tests in June 2003 concluded that not all were met.[41] The policy of the 2010s coalition government, elected in 2010, was against introducing the euro prior to the 2015 general election.[42] The United Kingdom ultimately withdrew from the European Union in 2020, leaving Denmark as the only state with the opt-out.

Although not a full opt-out, both Poland and former member state the United Kingdom secured a protocol that clarified how the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, a part of the Treaty of Lisbon, would interact with national law in their countries limiting the extent that European courts would be able to rule on issues related to the Charter if they are brought to courts in Poland or the United Kingdom.[43] Poland's then ruling party, Law and Justice, mainly noted concerns that it might force Poland to grant homosexual couples the same kind of benefits that heterosexual couples enjoy,[44] while the United Kingdom was worried that the Charter might be used to alter British labour law, especially as relates to allowing more strikes.[45] The European Scrutiny Committee of the British House of Commons, including members of both the Labour Party and the Conservative Party, cast doubts on the protocol's text, asserting that the clarification might not have been worded strongly and clearly enough to achieve the government's aims.[46][47][48] The United Kingdom ultimately withdrew from the European Union in 2020, leaving Poland as the only state with this particuar opt-out.

The Schengen Agreement abolished border controls between those of the EC member states which acceded to it. When the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 incorporated it into the EU treaties, Ireland and the United Kingdom (a member state at the time) received opt-outs from implementing the Schengen acquis as they were the only EU member states that had not signed the agreement. The UK formally requested to participate in certain provisions of the Schengen acquis: Title III relating to Police Security and Judicial Cooperation – in 1999, and this was approved by the Council of the European Union on 29 May 2000.[49] The United Kingdom's participation in some of the previously approved areas of cooperation was approved in a 2004 Council decision that came into effect on 1 January 2005.[50] A subsequent Council decision in 2015 approved the implementation of the provision on data protection and Schengen Information System to the UK.[51]

Under Protocol 36 of the Lisbon Treaty, the United Kingdom had the option to opt out of all the police and criminal justice legislation adopted prior to the treaty's entry into force which had not been subsequently amended. The decision to opt out had to be made at least six months prior to the aforementioned measures coming under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice on 1 December 2014. The UK informed the European Council of their decision to exercise their opt-out in July 2013,[52] and as such, the aforementioned legislation ceased to apply to the UK as of 1 December 2014.[53][54] While the protocol only permitted the UK to either opt out from all the legislation or none of it, they subsequently opted back into some measures.[55][56][57]

Opt-outs of Denmark

The Edinburgh Agreement of 1992 included a guarantee to Denmark that they would not be obliged to join the Western European Union, which was responsible for defence. Additionally, the agreement stipulated that Denmark would not take part in discussions or be bound by decisions of the EU with defence implications. The Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 included a protocol that formalised this opt-out from the EU's Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). As a consequence, Denmark was excluded from foreign policy discussions with defence implications and did not participate in foreign missions with a defence component.[58]

Following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022, the Danish government announced that a referendum would be held on 1 June on abolishing its opt-out in this area.[59] The political parties Venstre, the Danish Social Liberal Party and the Conservative Party had previously supported ending the opt-out, with the Socialist People's Party and the leading Social Democrats changing their position in the aftermath of the crisis. Right-wing parties the Danish People's Party and the New Right, as well as the left-wing Unity List, continued to oppose the move. The result of the referendum was a vote of 66.9% in favour of abolishing the defence opt-out. The opt-out was abolished on 20 June 2022.[60]

Former proposals

United Kingdom

Following the announcement by the government of the United Kingdom that it would hold a referendum on withdrawing from the European Union, an agreement was reached between it and the EU on renegotiated membership terms should the state vote to remain a member. In addition to a number of amendments to EU Regulations which would apply to all states, a legal guarantee would be granted to the UK that would explicitly exempt it from the treaty-stated symbolic goal of creating an "ever closer union" by deepening integration.[61] This guarantee was included in a Decision by the European Council, with the promise that it would be incorporated into the treaties during their next revision.[62] However, following the referendum, in which the UK voted to leave the EU, per the terms of the Decision the provisions lapsed.

Czechia

In 2009, Czech President Václav Klaus refused to complete ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon unless the Czech Republic was given an opt-out from the Charter of Fundamental Rights, as Poland and the United Kingdom had been with Protocol 30. He feared that the Charter would allow the families of Germans who were expelled from territory in the modern-day Czech Republic after the Second World War to challenge the expulsion before the EU's courts.[63] However, legal experts have suggested that the laws under which the Germans were expelled, the Beneš decrees, did not fall under the jurisdiction of EU law.[64] In October 2009, EU leaders agreed to amend the protocol to include the Czech Republic at the time of the next accession treaty.[65][66]

In September 2011, the Czech government formally submitted a request to the Council that the promised treaty revisions be made to extend the protocol to the Czech Republic,[67] and a draft amendment to this effect was proposed by the European Council.[68] However, the Czech Senate passed a resolution in October 2011 opposing their accession to the protocol.[69] When Croatia's Treaty of Accession 2011 was signed in late 2011, the Czech protocol amendment was not included. In October 2012, the European Parliament Constitutional Affairs Committee approved a report that recommended against the Czech Republic's accession to the Protocol.[70] On 11 December 2012, a third draft of the European Parliament's committee report was published,[71] and on 22 May 2013[68] the Parliament voted in favour of calling on the European Council "not to examine the proposed amendment of the Treaties".[67][68][72] The Parliament did, however, give its consent in advance that a treaty revision to add the Czech Republic to Protocol 30 would not require a new convention.[73] In January 2014, the new Czech Human Rights Minister Jiří Dienstbier Jr. said that he would attempt to have his country's request for an opt-out withdrawn.[74][75] This was confirmed on 20 February 2014 by the new Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka, who withdrew the request for an opt-out during a meeting with President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso[76][77][78][79] shortly after his newly elected government won the confidence of Parliament.[80] In May 2014, the Council of the European Union formally withdrew their recommendation to hold an Intergovernmental Conference of member states to consider the proposed amendments to the treaties.[81][82][83][84]

See also

- Freedom of movement for workers

- Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification in the European Union

- Multi-speed Europe

- Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a related concept in United States politics

- Opting out, a similar concept in Canadian politics

- Special member state territories and the European Union

- Brexit

- United Kingdom opt-outs from EU legislation

- Differentiated integration

Notes

References

- Parliament of the United Kingdom (12 March 1998). "Volume: 587, Part: 120 (12 Mar 1998: Column 391, Baroness Williams of Crosby)". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- See Protocol (No 21) on the position of the United Kingdom and Ireland in respect of the Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice (page 295 of the PDF)

- Charter, David & Elliott, Francis (13 October 2007). "Will the British ever be given a chance to vote on their future in Europe?". The Times. UK. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Miller, Vaughne (19 October 2011). "UK Government opt-in decisions in the Area ofFreedom, Security and Justice". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Publications Office (10 November 1997). "Article 2". Protocol on the application of certain aspects of Article 7a of the Treaty establishing the European Community to the United Kingdom and to Ireland, attached to the Treaty of Amsterdam. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- "Expanding Schengen outside the Union". 10 January 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Council Decision (2002/192/EC) of 28 February 2002 concerning Ireland's request to take part in some of the provisions of the Schengen acquis (OJ L 64, 7 March 2002 p. 20)

- Collins, Stephen (24 October 2007). "Irish will need passports to visit Britain from 2009". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- Dáil Éireann (24 October 2007). "Vol. 640 No. 2". Dáil Debate. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- Parliament of the United Kingdom (2 March 2007). "9th Report of 2006/07, HL Paper 49". Schengen Information System II (SIS II), House of Lords European Union Committee (Sub-Committee F). Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2020/1745 of 18 November 2020 on the putting into effect of the provisions of the Schengen acquis on data protection and on the provisional putting into effect of certain provisions of the Schengen acquis in Ireland (OJ L 393, 23 November 2020, p. 3)

- Peers, Steve (2011). EU Justice and Home Affairs Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199604906.

- Article 4(2) in Protocol (No 22) annexed to the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- Papagianni, Georgia (2006). Institutional and policy dynamics of EU migration law. Leiden: Nijhoff. p. 33. ISBN 9004152792.

- Europolitics (7 November 2007). "Treaty of Lisbon – Here is what changes!" (PDF). Europolitics № 3407. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- "Denmark to vote on Justice and Home Affairs opt-in model on 3 December". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. 21 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- European Parliament (10 October 2007). "MEP debate forthcoming crucial Lisbon summit and new Treaty of Lisbon". Press Service. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Staff writer (5 October 2007). "Finland's Thors blasts Poland over EU rights charter". NewsRoom Finland. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Staff writer (22 October 2007). "Poland's new government will adopt EU rights charter: official". EUbusiness. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- Staff writer (25 October 2007). "Poland will ponder before signing EU rights deal". EUbusiness. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- Staff writer (23 November 2007). "No EU rights charter for Poland". BBC News. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- "UCHWAŁA – Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 20 grudnia 2007 r. w sprawie traktatu reformującego UE podpisanego w Lizbonie 13 grudnia 2007 r." Sejm. 20 December 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Staff writer (4 December 2007). "Russia poll vexes EU and Poland". BBC News. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- "Karta Praw Podstawowych nie musi być ratyfikowana. 'Bo obowiązuje'" (in Polish). 14 September 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Siwiec pyta Sikorskiego o Kartę Praw Podstawowych" (in Polish). 9 September 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Kongres SLD. Wybór nowych władz partii" (in Polish). 28 April 2012. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "WRITTEN EVIDENCE FROM ANDREW DUFF MEP". 6 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Miles, Lee (28 June 2005). The European Union and the Nordic Countries. Routledge. ISBN 9781134804061.

- "Denmark and the Treaty on European Union". Official Journal of the European Communities. 31 December 1992. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- Crosbie, Judith (12 May 2009) Ireland seeks sign-off on Lisbon treaty guarantees, European Voice

- Smyth, Jamie (2 April 2009) MEP queries legal basis for Ireland's Lisbon guarantees, The Irish Times

- "2011/0815(NLE) – 06/10/2011 Legislative proposal". European Parliament. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Irish Lisbon guarantees approved". The Irish Times. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Irish Protocol) – Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs". TheyWorkForYou.com. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Protocol on the concerns of the Irish people on the Treaty of Lisbon details". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- "MEP Gallagher welcomes EP support for Ireland's protocol to the Lisbon Treaty". noodls.com. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "COMUNICATO: Entrata in vigore del Protocollo concernente le preoccupazioni del popolo irlandese al Trattato di Lisbona, fatto a Bruxelles il 13 giugno 2012. (14A09644) (GU Serie Generale n.292 del 17-12-2014)". Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della cooperazione internazionale). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Dale, Reginald (6 May 1997). "THINKING AHEAD/Commentary : Is Blair Leading a Continental Drift?". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Johnson, Ailish (2005). "Vol. 8 Memo Series (Page 6)" (PDF). Social Policy: State of the European Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Agreement on Social Policy". Eurofound. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Staff writer (11 December 2003). "Euro poll question revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "David Cameron and Nick Clegg pledge 'united' coalition". BBC. 12 May 2010.

- European Parliament (10 October 2007). "MEP debate forthcoming crucial Lisbon summit and new Treaty of Lisbon". Press Service. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Staff writer (5 October 2007). "Finland's Thors blasts Poland over EU rights charter". NewsRoom Finland. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Williams, Liza (9 October 2007). "Should a referendum be held on EU treaty?". Liverpool Daily Post. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Branigan, Tania (10 October 2007). "MPs point to flaws in Brown's 'red line' EU treaty safeguards". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Wintour, Patrick (12 October 2007). "Opt-outs may cause problems, MPs warn Brown". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- European Scrutiny Committee (2 October 2007). "European Union Intergovernmental Conference". European Scrutiny – Thirty-Fifth Report. British House of Commons. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- Council Decision (2000/365/EC) of 29 May 2000 concerning the request of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to take part in some of the provisions of the Schengen acquis (OJ L 131, 1 June 2000, p. 43)

- Council Decision (2004/926/EC) of 22 December 2004 on the putting into effect of parts of the Schengen acquis by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (OJ L 395, 31 December 2004, p. 70)

- Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/215 of 10 February 2015 on the putting into effect of the provisions of the Schengen acquis on data protection and on the provisional putting into effect of parts of the provisions of the Schengen acquis on the Schengen Information System for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (OJ L 36, 12 February 2015, p. 0)

- "Decision pursuant to Article 10(5) of Protocol 36 to The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. July 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- "List of Union acts adopted before the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in the field of police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters which cease to apply to the United Kingdom as from 1 December 2014 pursuant to Article 10(4), second sentence, of Protocol (No 36) on transitional provisions". Official Journal of the European Union. C (430): 17. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "List of Union acts adopted before the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in the field of police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters which have been amended by an act applicable to the United Kingdom adopted after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty and which therefore remain applicable to the United Kingdom as amended or replaced". Official Journal of the European Union. C (430): 23. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "2014/858/EU: Commission Decision of 1 December 2014 on the notification by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of its wish to participate in acts of the Union in the field of police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters adopted before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon and which are not part of the Schengen acquis". Official Journal of the European Union. L (345): 6. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "2014/857/EU: Council Decision of 1 December 2014 concerning the notification of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland of its wish to take part in some of the provisions of the Schengen acquis which are contained in acts of the Union in the field of police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters and amending Decisions 2000/365/EC and 2004/926/EC". Official Journal of the European Union. L (345): 1. 1 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Miller, Vaughne (20 March 2012). "The UK's 2014 Jurisdiction Decision in EU Police and Criminal Justice Proposals" (PDF). European Parliament Information Office in the United Kingdom. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "EU – The Danish Defence Opt-Out". Danish Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Yes or no? Now Danes must decide whether they want to fully integrate into the EU's defense policy" (in Danish). Danmarks Radio. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "Denmark joins EU's Common Security and Defence policy in historic move". 20 June 2022.

- "Britain should stay in the European Union". The Washington Post. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "European Council meeting (18 and 19 February 2016) – Conclusions". European Council. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- David Charter (13 October 2009). "I will not sign Lisbon Treaty, says Czech President". The Times. London. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- Vaughne Miller (9 November 2009). "The Lisbon Treaty: ratification by the Czech Republic" (PDF). The House of Commons Library. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

Steve Peers (12 October 2009). "The Beneš Decrees and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights" (PDF). Statewatch. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009. - Council of the European Union (1 December 2009), Brussels European Council 29/30 October 2009: Presidency Conclusions (PDF), 15265/1/09 REV 1, archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2009, retrieved 23 January 2010

- Andrew Gardner (29 October 2009). "Klaus gets opt-out". European Voice. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "European Parliament resolution of 22 May 2013 on the draft protocol on the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to the Czech Republic (Article 48(3) of the Treaty on European Union) (00091/2011 – C7-0385/2011 – 2011/0817(NLE))". 22 May 2013.

- "Application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to the Czech Republic. Protocol (amend.)". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "SECOND DRAFT REPORT on the draft protocol on the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to the Czech Republic (Article 48(3) of the Treaty on European Union)". European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Duff welcomes vote against Czech attack on Charter". Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. 9 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Third draft report – on the draft protocol on the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to the Czech Republic (2011/0817 NLE)". European Parliament. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "Press Release". alde.eu. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "European Parliament decision of 22 May 2013 on the European Council's proposal not to convene a Convention for the addition of a Protocol on the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to the Czech Republic, to the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (00091/2011 – C7-0386/2011 – 2011/0818(NLE))". 22 May 2013.

- "Dienstbier as minister wants scrapping of EU pact's Czech opt-out". Prague Daily Monitor. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- "Jiří Dienstbier chce, aby Česko požádalo o zrušení výjimky v Lisabonské smlouvě". 29 January 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Fox, Benjamin (20 February 2014). "Czech government to give up EU Charter opt-out". Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Premiér Sobotka se v Bruselu setkal s předsedou Evropské komise Barrosem i předsedou Evropského parlamentu Schulzem". Government of the Czech Republic. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Bydžovská, Maria (20 February 2014). "Barroso: ČR "resetovala" vztahy s EU". Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Czech prime minister in Brussels". Radio Prague. 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Czechs give up EU rights charter opt-out, plan joining fiscal pact". Reuters. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Press release – 3313th Council meeting" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 13 May 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "List of "A" items". Council of the European Union. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ""I/A" item note" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 8 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Procedure file – 2011/0817(NLE)". European Parliament. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

Further reading

- Howarth, David (1994). "The Compromise on Denmark and the Treaty on European Union: A Legal and Political Analysis". Common Market Law Review. 34 (1): 765–805. doi:10.54648/COLA1994039. S2CID 151521949.

- Butler, Graham (2020). "The European Defence Union and Denmark's Defence Opt-out: A Legal Appraisal" (PDF). European Foreign Affairs Review. 25 (1): 117–150. doi:10.54648/EERR2020008. S2CID 216432180.

External links

- Eurofound – Opt-out

- Denmark and the European Union, Danish Ministry for Foreign Affairs