European Ombudsman

The European Ombudsman is an inter-institutional body of the European Union that holds the institutions, bodies and agencies of the EU to account, and promotes good administration. The Ombudsman helps people, businesses and organisations facing problems with the EU administration by investigating complaints, as well as by proactively looking into broader systemic issues. The current Ombudsman is Emily O'Reilly.

| European Ombudsman | |

|---|---|

European Ombudsman logo | |

| Appointer | European Parliament |

| Inaugural holder | Jacob Söderman |

| Formation | 1995 |

| Website | ombudsman.europa.eu |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The European Ombudsman has offices in Strasbourg and Brussels.

History

The European Ombudsman was established by the Maastricht Treaty and the first, Jacob Söderman of Finland, was elected by Parliament in 1995. The current Ombudsman, Emily O'Reilly of Ireland, took office on 1 October 2013.

Appointment

The European Ombudsman is elected by the European Parliament. The Ombudsman is elected for the term of 5 years and the term is renewable. At the request of Parliament, the Ombudsman may be removed by the Court of Justice if "(s)he no longer fulfils the conditions required for the performance of his duties or if (s)he is guilty of serious misconduct". (Article 228 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU)

Remit and powers

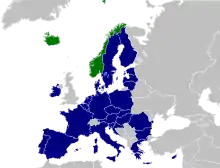

Any EU citizen or entity may appeal the Ombudsman to investigate an EU institution on the grounds of maladministration: administrative irregularities, unfairness, discrimination, abuse of power, failure to reply, refusal of information or unnecessary delay. The Ombudsman cannot investigate the European Court of Justice in its judicial capacity, the General Court, the Civil Service Tribunal, national and regional administrations (even where EU law is concerned), judiciaries, private individuals or corporations.[1]

The Ombudsman has no binding powers to compel compliance with their rulings, but the overall level of compliance is high. The Ombudsman primarily relies on the power of persuasion and publicity.[2] In 2011, the overall rate of compliance by the EU institutions with their suggestions was 82%. The EU Agencies had a compliance rate of 100%. The compliance rate of the European Commission was the same as the overall figure of 82%, while the European Personnel Selection Office (EPSO) scored 69%.[3]

Cases

It is a right of an EU citizen, according to the EU treaties, to take a case to the Ombudsman.[4] One example of a case dealt with by the Ombudsman involved a late payment from the commission to a German science journalist. The Commission explained the delay, paid interest and accelerated future payments to experts. On another occasion, following a complaint from a Hungarian, EPSO agreed to clarify information in recruitment competition notices concerning eligibility and pre-selection tests. A third case was resolved when the Ombudsman compelled the council to release to the public documents it had previously not acknowledged the existence of.[1]

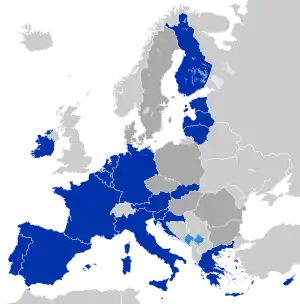

The ombudsman received 2,667 complaints in the year 2010 and opened 335 investigations into alleged maladministration. In 2011 2,510 complaints were received and 396 investigations were opened. The largest number of complaints in 2011 came from Spain (361), followed by Germany with 308. Relative to population, however, the greatest proportion of complaints came from Luxembourg and Cyprus.[5] The United Kingdom, despite its eurosceptic reputation, was in 2009 responsible for the smallest number of cases lodged.[2] In 2011 the UK was responsible for 141 complaints to the Ombudsman, still representing a relatively low ratio of complaints to population.[5]

According to the Ombudsman's own reports, 58% of complaints in 2011 were related to the European Commission. 11% related to the European Personnel Selection Office (EPSO) from dissatisfied applicants to the European Civil Service and 4% to the European Parliament. The Council of the European Union accounted for 3%.[5]

Main subjects of action

The main mission guiding the European Ombudsman's work is the “right to good administration” that is recognized as a human right in the EU.[6] The European Ombudsman helps citizens, companies and associations that face problems with EU administration. The main areas of inquiries of European Ombudsman relate to the transparency of EU institutions administration; transparency and accountability in EU decision-making; lobbying transparency; ethical issues; fundamental rights; EU competitions policy; and citizen participation in EU decision-making.

Transparency in the right of accessing EU documents

Complaints concerning lack of transparency are the most common category of complaints received by the European Ombudsman, representing between 20% and 30% of complaints. They are mainly related to the refusal of EU institution(s) to grant documents upon a citizen's request. This right of citizens to access EU documents is granted by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. In case a citizen is prevented from accessing such requested documents, he or she can turn with a complaint to the European Ombudsman to try to achieve a resolution. For instance, in case 693/2011/RA, following European Medicines Agency (EMA)'s refusal to grant public access to clinical studies carried out on a multiple sclerosis drug, the Ombudsman made a friendly solution proposal on it with some detailed suggestions for the particular case, trying to achieve the transparency the complainant was requesting. EMA positively received this and fully accepted the friendly solution proposal by European Ombudsman.

Lobbying transparency

European Ombudsman works to ensure that the EU's democratic decision-making process is characterized by the highest transparency standards. For that, special attention is given to interest groups and their engagement and influence in EU institutions. Lobbying transparency is one of the main topics of action of the European Ombudsman, through various strategic initiatives, trying to mitigate potential conflicts of interest. The European Ombudsman was involved in the Transparency Register, which has enabled citizens to know who is trying to influence EU decision-makers. For instance, in 2014, the European Ombudsman published, after a formal inquiry, a final decision stating that the “Commission's refusal to publish online details of all meetings which its services and its staff have with the tobacco industry” constituted maladministration.[7]

Ethical issues

Ethic issues related complaints to European Ombudsman can go from conflicts of interest to “revolving doors” situations, where someone working in the private sector moves to closely links jobs in the public jobs or vice versa. The European Ombudsman has defended that EU administration must comply with “gold standards when it comes to ethical behaviour”.[8]

For instance, one inquiry, concluded in 2020, investigated corporate sponsorship of the Presidency of the Council of the EU. Started from a complaint NGO who raised the concern of the Romanian EU Presidency receiving sponsorship by a major soft drinks company in the context of the Presidency. The Ombudsman considered[9] that “as the Presidency is part of the Council, its activities are likely to be perceived by the wider European public as being linked to the Council of the EU as a whole” and might entail “reputational risks”. The Council ended up agreeing to the European Ombudsman consideration and drew guidance for Member States indicating that they would no longer accept sponsorship in the context of their presidencies.

Fundamental rights

A key part of European Ombudsman work is to ensure that EU institutions respect fundamental rights. For example, in 2015 the European Ombudsman conducted an investigation,[10] in collaboration with 19 members of the European Network of Ombudsmen, into the compliance of fundamental rights by Frontex when forcing migrants to return to their home countries. It concluded that there was significant “room for improvement” as to how it was handling joint returns of illegal migrants and, in that scope, made detailed recommendations as to how Frontex could improve. Frontex responded positively to many of these recommendations.[11]

Citizen participation

In its role as moderator and bridge between citizens and the EU institutions, the European Ombudsman also promotes citizens' participation and involvement in European politics, by, for example, demanding greater transparency so that citizens can follow the proceedings, or by promoting on his own initiative the implementation of more participatory decision-making processes. A large number of the complaints that the European Ombudsman receives in this context are related to problems in the functioning of the European Commission's public consultations, and the European Citizens' Initiative (ECI). In 2014, the European Ombudsman invited ECI organizers (such as civil society, organisations and interested bodies) to give feedback on the ECI.[8]

European Ombudsman's procedures

The European Ombudsman, on one hand, a formal parliamentary body at a supranational level, “designed to strengthen the supervision and control of European Institutions and Administrations” and, on top of that, it works with a specific European concept of maladministration. The powers of the European Ombudsman, albeit limited, provide them the “opportunity to combine the instruments of parliamentary scrutiny and judicial control in an original way”[12]

European Ombudsman can conduct inquiries following a complaint received and conduct inquiries on its own initiative. As methods of action, it can require the institution concerned for information, it can inspect the institution's files and it can take testimonies from officials.

The European Ombudsman complements the work of the courts, as it offers an alternative way for citizens to resolve disputes with the EU administration, without incurring in costs such as lawyers or fees. However, the European Ombudsman has no power to make legally binding decisions, so it can only act as a moderator in the dispute.

Using the powers conferred by the Statute of the European Ombudsman,[13] the European Ombudsman can require any institution whose maladministration is in question “to provide some information, inspect its files and take testimony from its staff members”[14] and it can propose solutions for the case.

Whenever it finds a situation of maladministration, the European Ombudsman can make proposals through problem-solving proposals, recommendations and suggestions. The main way in which the European Ombudsman tries to resolve the case is by proposing a solution,[15] that is, a solution that both the complainant and the institution concerned would be willing to accept. This method may result in a quick constructive and good outcome for the complainant. However, this method is far from being effective to provoke systemic change in the public interest.[16] If the institution rejects the proposed friendly solution, then the European Ombudsman can proceed to the powers of Article 4 of the Statute and draft recommendations for the institution concerned. Such recommendations are published in the Ombudsman's website, creating therefore some publicity and raising public attention to the maladministration identified.[17] If no resolution is found neither from the proposed friendly solution, nor from the recommendation, then the European Ombudsman can publish suggestions for improvements, directed to the institution, to address the issue.[18] These public suggestions can publicly identify systemic maladministration problems and suggest corrections that can cause systemic improvements for the public interest. If, at the end of an investigation, an institution rejects its final findings or recommendations, the Ombudsman can criticize it publicly, raising importance on the issue, and can make a special report to the European Parliament.

Many of the complaints sent to the European Ombudsman are outside its mandate. In 2020, the European Ombudsman processed 1,400 complaints outside its scope of competence. This number of out-of-scope complaints came mainly from Spain, Poland and Germany. This counts to justify the significant difference in percentage of opened inquiries compared to the number of complaints submitted.

In any case, the European Ombudsman tries to reply to all complaints submitted, even the ones outside the mandate. In those cases, European Ombudsman helps complainants by explaining the Ombudsman's mandate, advising other bodies where to direct their complaint. If the complainant agrees, the European Ombudsman can also forward the complaint to members of the European Network of Ombudsmen (ENO).

The institution receiving the greatest number of inquiries conducted by the European Ombudsman has been throughout the years the European Commission. In 2020 for example, 210 inquiries opened concerned the European Commission, compared to 30 concerning the European Personnel Selection Office, 14 the European External Action Service, 12 the European Anti-Fraud Office, 11 the European Parliament, 9 the European Central Bank, 9 the European Investment Bank, 34 for EU agencies and 41 to all other organisms.

The major grand topic inquiries made by European Ombudsman in 2020 were: the functioning of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency's (Frontex) 'Complaints Mechanism' to deal with complaints related to fundamental rights; the transparency of the Council of the EU during the Covid-19 crisis; and the collection and processing of information by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control during the Covid-19 crisis.

Advice, complaints, and inquiries throughout the years[19]

| 2014 | 2015 | 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “People helped by the European Ombudsman” | 23 072 | 17 033 | 15 837 | 20 302 |

| “Advice given through the Interactive Guide on the Ombudsman's website” | 19 170 | 13 966 | 12 521 | 16 892 |

| “New complaints managed” | 2 079 | 2 077 | 2 181 | 2 148 |

| “Requests for information replied to by Ombudsman” | 1 823 | 1 060 | 1 135 | 1 262 |

| “Inquiries opened” | 342 | 261 | 447 | 370 |

| “Inquiries opened based on complaints” | 325 | 249 | 433 | 365 |

| “Own-initiative inquiries opened” | 17 | 12 | 14 | 5 |

| “Inquiries closed” | 400 | 277 | 363 | 394 |

| “Complaint-based inquiries closed” | 387 | 261 | 348 | 392 |

| “Own-initiative inquiries closed” | 13 | 16 | 15 | 2 |

The high number of maladministration complaints made to European Ombudsman in parallel with the literature support, shows that “the ombudsman is an important platform protecting the rights of citizens and promoting democratic values at the EU level”.[20]

Effectiveness, impact, and achievements

The European Ombudsman has, since its appearance in 1995, profiled itself as an institution with the “good governance” mission, promoting this cause and its own place within the EU institutional system.[21] It is active towards serving the wider public interest and one of its goals is to achieve “tangible improvements for complainants and the public vis-a-vis the EU administration”[22] On one hand, European Ombudsman is responsive towards complaints from individuals, companies and associations, replying to and resolving complaints related to administration problems in the EU institutions. On the other hand, the European Ombudsman also takes an autonomous and active approach in “helping the institutions to improve the quality of the service they provide”[23] by making proposals through problem-solving proposals, recommendations, and suggestions.

Accessing the European Ombudsman's effectiveness implies having into consideration quantitative data, such as the statistics of the responsiveness to complaints and statistics on own-initiative inquiries, but also qualitative data in order to try to better understand all kinds of achievements when contacting the institutions (that is, how EU institutions react to the European Ombudsman's proposals).

For this purpose, complying with Article 4(5) of the Statute,[24] the European Ombudsman submits a comprehensive report to the European Parliament at the end of each annual session, with information on the rate of EU institutions’ compliance with recommendations made by the European Ombudsman.

One of the goals of the European Ombudsman is to achieve improvements in the EU administration and, according to its way of working, statistics can partially measure their results, in terms of how the institutions responded to the Ombudsman's proposals.

European Ombudsman's responsiveness to complaints

Data from the 2020 Annual Report[22] shows how responsive the European Ombudsman was in 2020 towards the complaints received by individuals, companies, and associations, including the complaints that were outside its mandate scope (which were more than 1400 in 2020). In 2020, 849 complainants (39.5% of all complaints dealt with during 2020) received advice or found their case transferred to another complaints body. Other 934, (representing 43,5%) received a response informing the complaint that all advice from European Ombudsman had already been provided. Finally, 365 complaints (17% of all complaints dealt with that year) resulted in the opening of formal inquiries for further analyses.

Cooperation and acceptance by EU institutions

European Ombudsman reports that[14] in 2019, “the EU institutions responded positively to the Ombudsman's proposals (solutions, recommendations, and suggestions) in 79% of instances”. Out of 119 proposals from the Ombudsman related to corrections the EU institutions should do to improve their administrative practices, 95 were positively received and had an influence on the correction of the maladministration situations detected. In 2020, 10 out of the 17 institutions to which the Ombudsman made proposals, fully complied with all solutions, suggestions, and recommendations.

Some examples of influence

- Case 2168/2019/KR:[25] Revolving doors.[26] European Ombudsman opened an inquiry after the ex-executive director of the European Banking Authority moved to the position of CEO of the Association for Financial Markets in Europe. The European Ombudsman concluded that the EBA should have forbidden such move of job, given the high risks of conflict of interests. Therefore, a recommendation was made that, in the future, the EBA should forbid, with clear criteria, senior staff members moving to certain positions after their term of office and access to confidential information would stop once it was known that a member of staff was taking up another job. The EBA agreed to implement the Ombudsman's recommendations.

- Case 860/2018/THH: positive cooperation following European Food Safety Authority's refusal to grant public access to declarations of interest of middle management staff. The EFSA ended up following the Ombudsman's request to make those declarations public and has a more transparent policy in this area.

- Case 357/2019/FP: positive cooperation following the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)'s refusal to grant public access to documents relating to contacts with stakeholders. The European Ombudsman opened an inquiry following a complaint and verified that some internal notes of meetings should have been disclosed. In the context of cooperation with the European Ombudsman, the ESMA disclosed to the complainant parts of eight documents.

- Joint cases 488/2018/KR and 514/2018/KR: positive cooperation in the context of an inquiry regarding the appointment of the Commission's Secretary-General (its highest civil servant). The Commission improved the appointment procedure as it had been suggested by the European Ombudsman, indicating a vacancy notice and a well-defined timeline in the procedure.

Conclusion

While the discourse on fundamental rights is relevant to the European Ombudsman, its profile and, to some extent, its mandate leave the conceptual field of human rights outside of its scope capacity to act. The mission and performance of the European Ombudsman is positively seen by the EU institutions, shown by the rates of positive cooperation and compliance with the European Ombudsman's recommendations. Most scholars note that the European Ombudsman has been effective in promoting good governance in the EU. However, a few author note that it has had less impact in the field of fundamental rights, subject EU citizens most complain about.[27]

Ombudsmen

| Ombudsman | In Office | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Jacob Söderman | 1995–2003 | |

| Nikiforos Diamandouros | 2003–2013 | |

| Emily O'Reilly | 2013–Incumbent |

See also

- European Citizens' Initiative, an initiative aimed at increasing direct democracy in the European Union.

References

- "The European Ombudsman—At a glance". ombudsman.europa.eu. July 2006. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Mackie, Christopher (18 March 2010). "The EU's 'invisible man' who has power over all our lives". The Scotsman.

- "Report on responses to proposals for friendly solutions and draft recommendations—How the EU institutions complied with the Ombudsman's suggestions in 2011". ombudsman.europa.eu. 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- . . 2007. Article 20 – via Wikisource.

- European Ombudsman (2012). European Ombudsman's Overview 2011. Publications Office. doi:10.2869/5243. ISBN 978-92-9212-326-0. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Demiret, Demokaan (2001). "The Role of the European Ombudsman in Good Administration". Aeupeaj. 5 (2): 127.

- European Ombudsman. "Decision concerning the European Commission's compliance with the Tobacco Control Convention (852/2014/LP)". European Ombudsman.

- European Ombudsman (2015). "Annual Report 2014". European Ombudsman.

- European Ombudsman (2021). "Looking Back the Impact of the European Ombudsman in 2020". European Ombudsman.

- Case OI/5/2012/BEH-MHZ

- However, Frontex did not follow the recommendation concerning that Fundamental Rights Officer should deal with complaints.

- Moure Pino, Ana María (2011). "The European Ombudsman in the Framework of the European Union". Revista Chilena de Derecho. 38 (3): 421–455. doi:10.4067/S0718-34372011000300002.

- "Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2021/1163 of the European Parliament of 24 June 2021 laying down the regulations and general conditions governing the performance of the Ombudsman's duties (Statute of the European Ombudsman) and repealing Decision 94/262/ECSC, EC, Euratom".

- European Ombudsman (2020). "Putting it Right? Report. How the EU institutions responded to the Ombudsman in 2019". European Ombudsman.

- Article 2 of the Statute

- European Ombudsman (2014). "Putting it Right? Report. How the EU institutions responded to the Ombudsman in 2013". European Ombudsman.

- Ibid.

- Article 1(4) of the Statute.

- Data from European Ombudsman, “Annual Report 2014”, “Annual Report 2015”, “Annual Report 2017”, and “Annual Report 2020”.

- Demokaan Demiret, op.cit., 140.

- Ian Harden, “The European Ombudsman's Role in Promoting Good Governance,” in Accountability in the EU. The Role of the European Ombudsman, ed. by Herwig C. H. Hofmann and Jacques Ziller (Celtenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), 198–216.

- European Ombudsman. "Annual Report 2020".

- Ibid.

- Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2021/1163 of the European Parliament, loc.cit.

- European Ombudsman (1 September 2020). "Press release n° 3/2020".

- Concept given for situations when staff members of EU institutions rotate from positions from private to public sector and vice versa.

- Tero, Erkkilä (2020). European Ombudsman as a Supranational Institution of Accountability," in Ombudsman as a Global Institution. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–174.

External links

- The official website of the European Ombudsman,

- The European Code of Good Administrative Behaviour, at the Ombudsman's official website

- Public service principles for the EU civil service, at the Ombudsman's official website